Picture an American artisan in your mind’s eye. What do you see? Here’s a guess: a sturdy fellow of middle age, likely white, tools in hand, wearing a leather apron. He works alone, or maybe with an apprentice or two. And he is long dead.

How accurate is this picture? We might start with the last point. It is certainly true that craft’s status as the bedrock of the economy was eroded long ago, with the onset of the industrial revolution. But in recent years a “maker movement” has swept the country. Advertisers and reality TV shows have seized on handwork for the seductive emotional ballast it offers in the digital age. And, ironically, digital selling platforms have made it vastly easier for specialist makers to also make a living. Craft is back in a big way.

The stereotype of the craftsman rooted in tradition, a proud standard-bearer of freedom and self-reliance, also doesn’t quite capture the truth. Consider the demographics: a good half of artisans were actually craftswomen, but they only rarely attained independent professional status, usually when widowed. In the antebellum period, many artisans were enslaved. Seamstresses and shipwrights, builders and blacksmiths, their labor—even when highly skilled— went uncompensated and was often performed in brutal conditions. And the highest concentration of craftspeople in the country was arguably to be found in its Native population. As they were driven from their homelands, they nonetheless retained an impressive repertoire of indigenous technologies, making them far more self-sufficient than the white population tended to be.

Then there is the question of where and how artisans worked. Many of the most successful— famous names like Paul Revere and Duncan Phyfe—were determined to put away their tools, and concentrate on the more profitable work of running a business. (We may take excessive pride in early American artisans’ handwork, but they generally did not.) Meanwhile, inside the very factories that displaced the craft-based economy, there were plenty of artisans at work: machine builders, pattern cutters, and skilled mechanics. This “labor aristocracy” was a relatively small part of the workforce, but without them, the industrial revolution could not have taken place.

All this history matters for the present. For all of craft’s reputation as a small-scale, traditional endeavor, the word actually describes a vast landscape, in which crucial aspects of national identity formation are at stake. These are the main themes of my recent book, Craft: An American History (Bloomsbury); and also of a current exhibition that I have co-curated, together with Jen Padgett and with the support of a team of advisors— including Bernard L. Herman, Anya Montiel, Seph Rodney, and Jenni Sorkin—for the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Simply entitled Crafting America, it surveys the past eighty years or so—close to the horizon of living memory—taking in work produced in classic craft mediums such as ceramics, glass, textiles, metal, and wood, and in some less expected genres, like electric guitars and pageant costumes.

It is a lot of ground to cover, and even a large exhibition (ours includes about 120 objects) can only hope to indicate general tendencies. To focus our effort, we established two key parameters. First, we would look at craft in adjacency to fine art, which is after all the remit of Crystal Bridges—this relatively new museum is best known for its collection of American paintings, many assembled by the museum’s founder, Alice Walton. While Crafting America does include objects that could be put to use, like chairs, bowls, and necklaces, everything in the show is primarily aesthetic in intention. Plumbers, machinists, and tailors are craftspeople too; and their work may well have a certain beauty to it. But we decided not to stray quite that far into the pragmatic domain.

Our second curatorial guideline was to place diversity at the forefront, especially with regard to gender and ethnicity. This, too, is an important aspect of Crystal Bridges’ mission. As I noted in a recent column for this magazine (September/October 2020), the first gallery that visitors encounter at the museum is dominated by an artwork by Nari Ward, spelling out the phrase We the People. Across the space, on the opposite wall, hangs a panoply of portraits, showing Americans of all backgrounds. We wanted to make a similarly emphatic statement about the state of American craft: it is the work of many hands and many communities.

In a sense, it was easy for us to make an unusually inclusive exhibition, for craft has long offered professional opportunities for women and people of color, in ways that fine art and architecture did not. But diversity, in itself, is not really an argument—just a fact of life. We wanted to show that craft’s rich variation of perspectives also makes it a positive cultural force, a means of thinking through identity, not just asserting it. With this in mind, we devised an overall exhibition structure inspired by the Declaration of Independence. The show is divided into three sections, entitled “Life,” “Liberty,” and the “Pursuit of Happiness.” Americans have inherited these core values, while also being aware that they have been unequally shared. Craft is a means of reflecting on these vexed and vital issues.

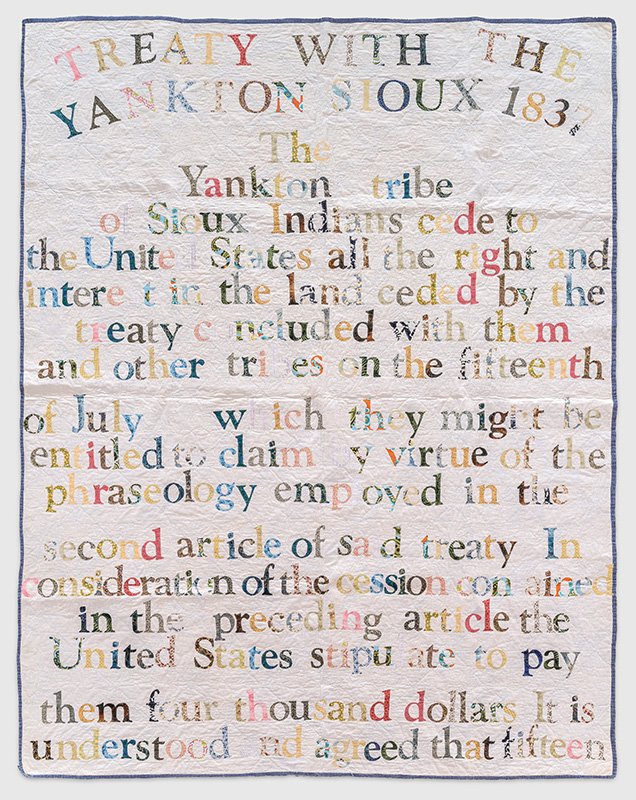

With this in mind, after a brief expository section—defining craft’s key features for the visitor— viewers encounter a patchwork of American identity. Here is a quilt made by the Women’s Society of Christian Service in the 1940s, honoring veterans of World Wars I and II from the Native community. Alongside it hangs another quilt, by artist Gina Adams, bearing the text from a onesided agreement between the US Government and the sovereign Yankton Sioux tribe, and which forms a part of the artist’s Broken Treaties series (Fig. 3). Also here is Consuelo Jimenez Underwood’s Home of the Brave, which adapts the format of the American flag to the materiality of a rag rug, with a band of Native American– style weaving and a conspicuously unwoven fringe at its lower edge (Fig. 1). These works sketch in some of the contours of the Native experience, while also emphasizing the hard truths of that American history.

The exhibition’s first main section, “Life,” considers craft as a part of everyday experience. It’s an intentionally low-key start, featuring humble but poignant objects like Gentaro Kenneth Hikogawa’s four-drawer chest, made in a Japanese-American incarceration camp during World War II. In this grim circumstance, Hikogawa—a traditionally trained cabinetmaker—scavenged wood from shipping crates for his furniture, adding handles in rough brushwood. He also helped to train a certain George Nakashima, a young architect who was also imprisoned in the camp—an experience that informed Nakashima’s later career as one of America’s leading studio furniture makers.

The centerpiece of the “Life” section is Beaded Prayers, a participatory artwork that Sonya Clark began more than twenty years ago (Fig. 5). It has grown through a series of workshops, involving over five thousand people from thirty-five countries, in which attendees are asked to write a wish on two slips of paper. Instead of sharing their “prayer” with anyone else, they are asked to enclose the papers in two packets, which they then stitch or tie shut, and embellish with beadwork. Participants keep one of these amulets, and the other joins the mass of the evergrowing artwork—a quiet but powerful tide of private hopes, buoyed by the elevating act of handwork.

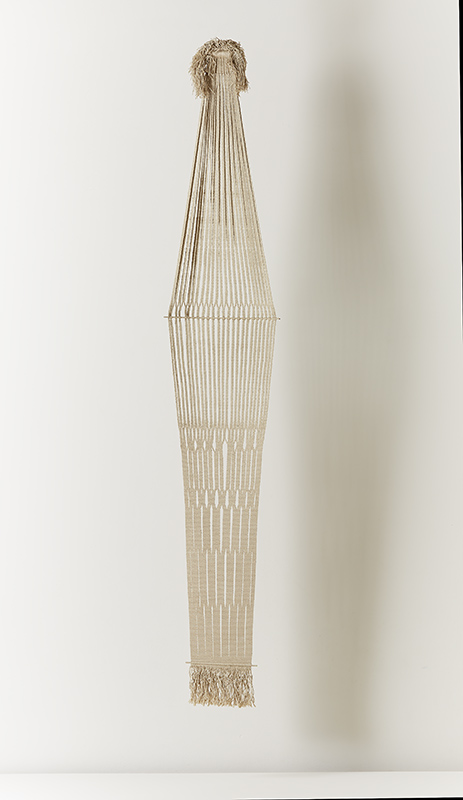

The second section of the exhibition, “Liberty,” offers a dramatic contrast, for here we look at the entry of gestural abstraction into American craft. This story begins in the 1950s, with figures like Peter Voulkos and Lenore Tawney—who brought their respective mediums of ceramics and weaving into direct dialogue with contemporaneous painting and sculpture—as well as singular artists like Ruth Asawa, whose volumetric wire sculptures, inspired equally by her time at Black Mountain College and by vernacular baskets she saw in Mexico, have attracted enormous attention in recent years. (Last year, she literally ended up on US postage stamps.) It continues today, in the work of artists like Arlene Shechet, Nicole Cherubini, and Diedrick Brackens. In this part of the show, craft recedes as subject matter, but comes even more strongly to the fore as process.

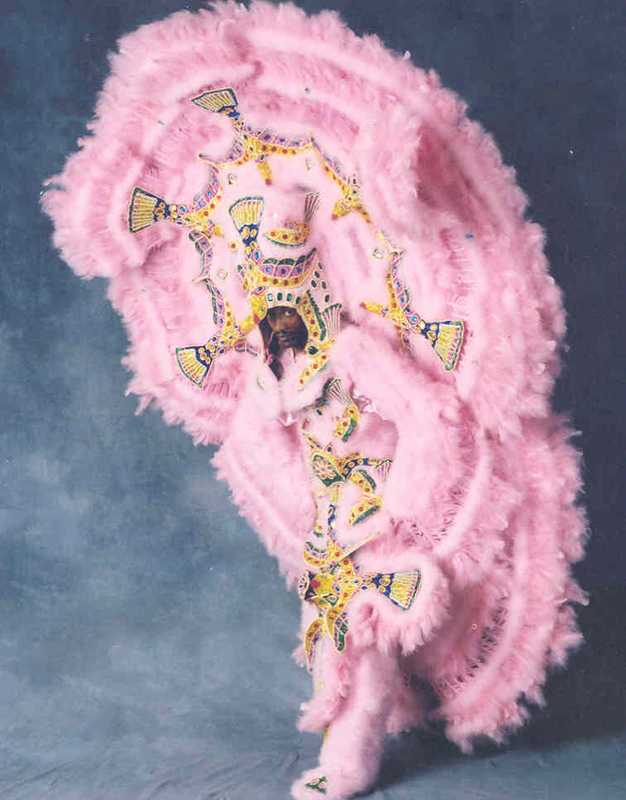

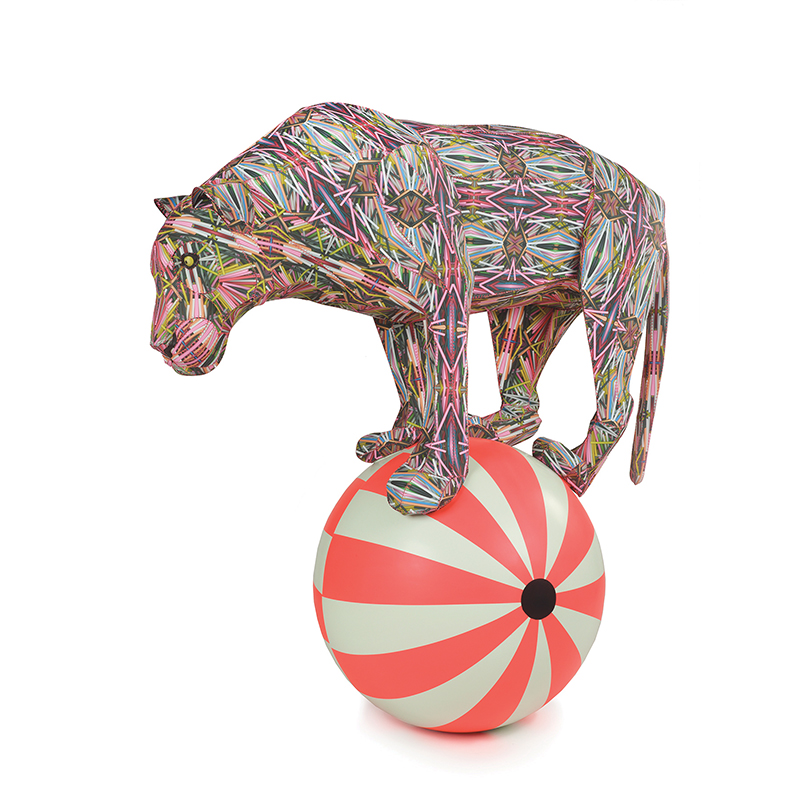

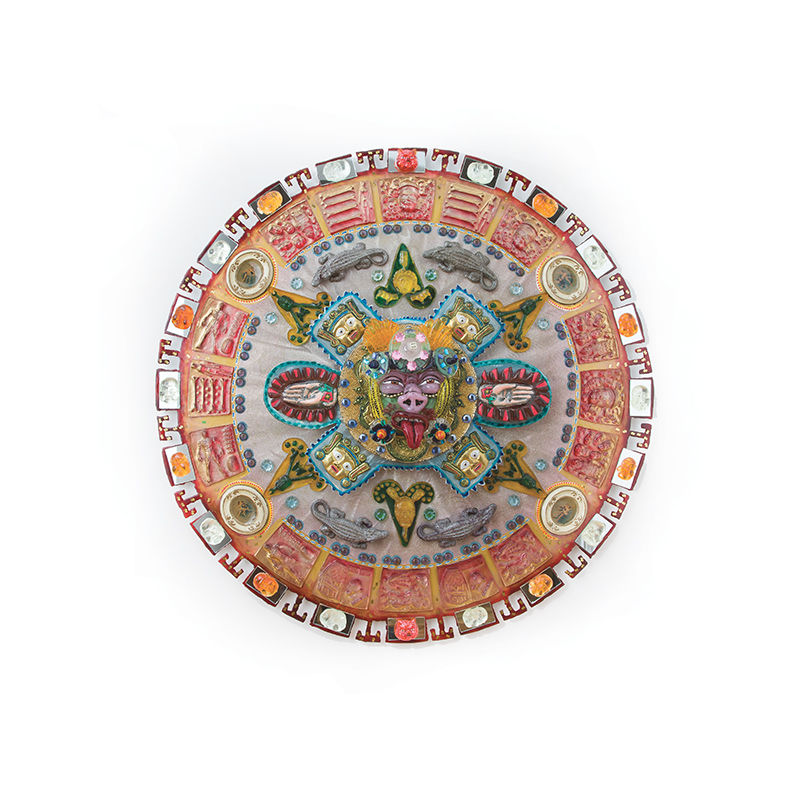

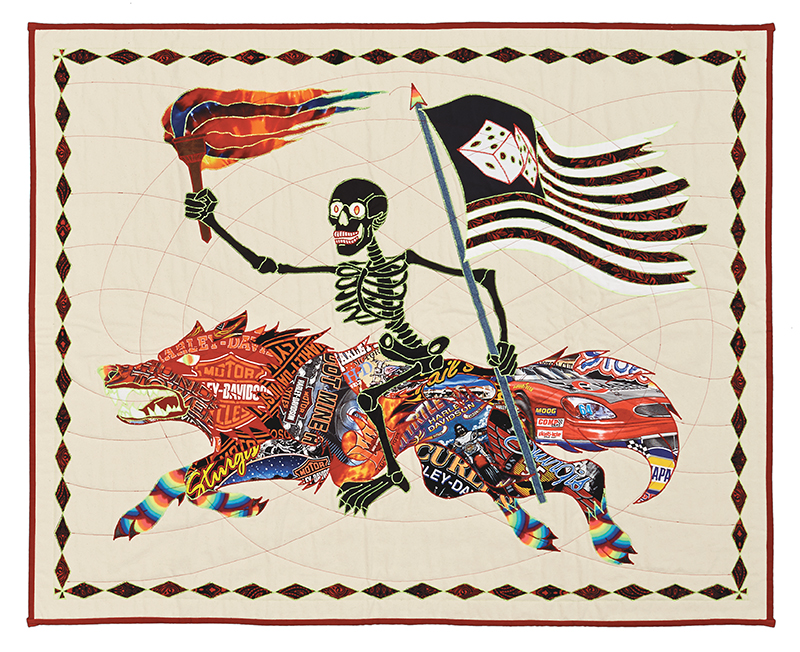

That vivid energy culminates in the show’s finale, the “Pursuit of Happiness,” which is populated by contemporary creations of strongly imaginative character: here’s where we have placed that guitar (a model originally designed for the rock star Prince) and a Mardi Gras costume made by “Big Chief” Darryl Montana, one of New Orleans’s most respected Carnival performers. Glass—an inherently spectacular medium—is an important presence in this last part of the exhibition, turned to unexpected purposes by makers like Einar and Jamex De La Torre, who reinterpret ancient Aztec symbolism in a contemporary pop idiom (Fig. 13). A sprawling wall piece by Ebony Patterson provides closure. Lush and polychrome, populated with found objects, it nonetheless has a sober underlying message, roadside shrines dedicated to people who have been violently killed (Fig. 7). Here, and in her other work, she expresses a spirit of deep empathy for the primarily masculine cultures— both creative and self-destructive—that can lead to such tragedy.

Patterson’s work, in which sorrow and joy are intricately intermingled, is a fitting end to an exhibition that surveys American craft at a time when America itself is undergoing unprecedented turbulence. Creating an exhibition in the middle of a pandemic is a strange experience. There will be no opening celebration, and I myself may not see the show until summertime. Meanwhile, the story continues: craft has been finding new purposes, as maker spaces convert themselves into fashioning protective medical gear, and even some of the least skilled among us have a try at sewing masks by hand. Craft embodies some of our nation’s best characteristics: creativity, resiliency, and yes, independence— but also solidarity. Here’s hoping that at this dark time, the resplendent pageant of American artisanship can provide at least a little illumination.