My father wasn’t especially fatherly. After I returned from a weekend at a classmate’s house when I was twelve years old, I asked him why he didn’t play with my brothers and me the way other dads did. I don’t recall his answer, if he had one, but we found an opportunity to bond when he started taking me to rare-book auctions in the mid-1960s at the Sotheby Parke-Bernet galleries on Madison Avenue.

Perhaps accusing him of being lazy had lit a spark. So he inculcated me in his passion: collecting rare American first editions. He owned the foremost collection of the works of Horatio Alger Jr. and, in 1964, published a biography of the bestselling “rags to riches” author that included the definitive bibliography.

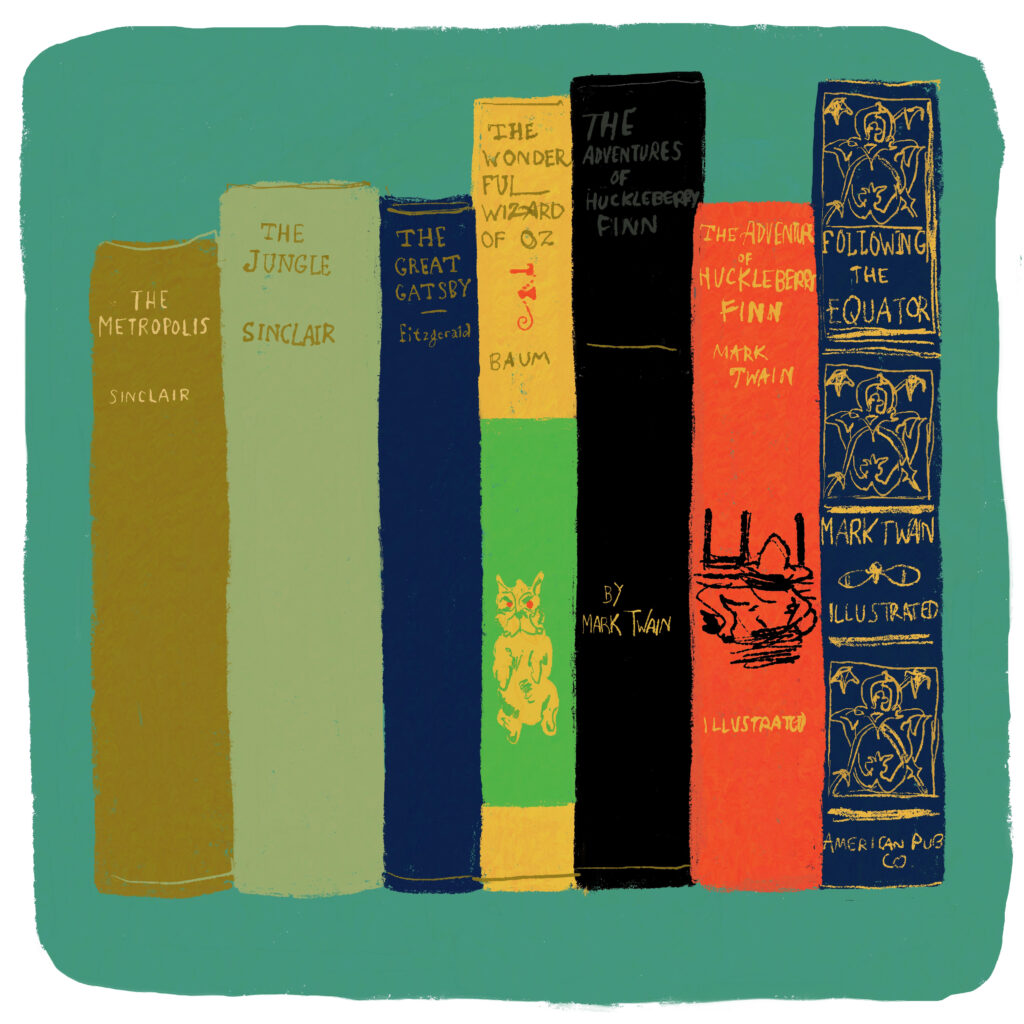

On weekends we’d cross Central Park, take our seats in the auction room, and he’d guide me as I bid on books that I’d read, in more humble paperback versions, for school or just for fun. My inaugural acquisition was an autographed first edition of Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle, his muckraking expose of the Chicago meatpacking industry.

On another weekend afternoon I successfully bid on an auction lot of John Steinbeck first editions, among them The Grapes of Wrath and East of Eden. The latter came autographed and in the original slip case. I have no recollection of what any of these treasures cost. Suffice it to say that they weren’t too far out of reach for a young collector who was willing to pool his birthday money together with a compassionate bump in his allowance.

I do remember the cost of my proudest acquisition. It didn’t emerge from under an auction gavel but from the dusty stacks of a rare book dealer in Princeton, New Jersey. I don’t believe it was my father’s initial intention to use my precocious interest in rare books as a ploy to burnish my Ivy League college admissions brag sheet. But he was obviously aware that my lackluster grades and SAT scores weren’t going to cut it at Yale or Princeton, my first-choice schools. So he set out to package me as a teenage bibliophile.

His campaign included having me join the Friends of the Princeton University Library. And on my way to my Yale interview, we dropped by the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library to pay our respects to the librarian, an acquaintance of my father’s, who courteously penned a letter in support of my application.

Sadly, I was denied acceptance to both Princeton and Yale. Apparently, their admissions offices didn’t deem knowing how to bid at auction a skill commensurate with captaining the state champion high school football team or being a cello prodigy. But my visit to Princeton, at least, hadn’t been a total wash. On the back shelf at that rare book dealer on Nassau Street I discovered a first edition of The Great Gatsby. The price, penciled on the inside front cover, was ten dollars. By the shop owner’s stunned reaction when I brought it to the counter, this rarity, and its outdated price, had slipped through the cracks.

The volumes I acquired back then still occupy pride of place on my bookshelf. I consider them modest gems of American literary history. They still give me a mild rush every time I pick them up and examine them. They also bear my father’s influence. He taught me to comb rare book catalogues and clip the price and the date of works that I owned. Thus, my first notation regarding The Great Gatsby came from a 1972 catalogue that was offering it for sixty dollars. By 2022 Bauman, a fancy rare-book seller, was advertising the first edition—like mine it didn’t boast the extremely rare and iconic dust jacket—for ninety-five hundred dollars.

It goes without saying that asking and selling prices aren’t necessarily the same thing. I was curious about the state of the rare book market in the digital age. Can one find a twenty-first century version of my pink-cheeked adolescent self haunting auction houses or scouring rare-book websites? Or are today’s teens, not to mention adults, too distracted playing Minecraft or watching TikTok videos to read books, let alone pay substantial sums for the privilege of possessing rarities?

Peter Costanzo, an expert at Doyle, which holds numerous rare book and manuscript auctions a year, described the market as “voracious” but with a caveat. “The Internet has been a game changer for rare books,” he says. “A lot of rare books started to appear less rare.” He meant that a visit to an online marketplace, such as AbeBooks, reveals Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man in the Sea, an example Costanzo offered, in everything from cheap paperbacks to multiple autographed first editions worth thousands of dollars.

It seems the sense of the hunt I experienced rooting around that ancient Princeton bookshop or bidding at auction has dissipated in the face of instant access. “There used to be more completist collectors,” Costanzo observes. “These days it’s more trophy hunting. The auction market for really special things has ratcheted up.” He cited a first edition of Shelley’s Prometheus Unbound with a jeweled binding that was coming up for auction at Doyle.

I own nothing bejeweled, but I suspected I possessed at least one book that met the expert’s elevated criteria: a copy of Huckleberry Finn I inherited from my father. Not the first edition, which he also passed down to me, but a much rarer salesman’s dummy. It’s a slim volume that booksellers would carry door to door—this one bore ten sales made in Bloomington, Illinois at $2.75 each—that included sample text, illustrations, and bindings. Costanzo agreed that the salesman’s dummy qualified as a rarity. He could find few that had come up for auction. My father claimed that Where the Wild Things Are author Maurice Sendak once offered him a painting in exchange for the salesman’s book, but my dad turned him down. I’m not sure it was a wise business decision—Costanzo placed the value of the dummy at between two and seven thousand dollars—but I’m glad that my father held onto it. I treasure it and it reminds me that whatever his flaws, my dad passed along a passion for rare books that still burns bright.