In 1887 a business venture called the Catskill Mountains Camp and Cottage Company incorporated, with offices at 116 Reade Street in New York City. The aim was to promote and populate a select community in the northern reaches of the Catskills, a place with healthful air, beautiful views, and rustic amenities in the form of an inn and a few small houses. You could stay at the inn—it had a French chef—rent a cottage, or buy a plot of land and have the company build you one, or you could simply pitch a tent in the woods for a few summer weeks. The place was called Onteora.

Unless you’ve visited this private park nestled high above Kaaterskill Falls, you might have trouble pronouncing the name (think of it as your Aunty Ora and you have it). It comes from the local Native American Munsee language and means “land in the sky” or “hills of the sky.” One of the oldest of America’s summer colonies, Onteora is a remarkable survivor, a holdover with a rich literary, artistic, theatrical, and musical past. The majority of its cottages still stand, as do its handsome library, theater, church, and field house. Shaded trails, an arboretum, golf course, tennis courts, a lake, and the same mountain views that inspired the Hudson River school painters round out the landscape.

To appreciate Onteora, you must know more about how it came to be and what it was like to spend summers there. This rustic Eden was one of the first of its kind, a new venture in real estate development and, at the same time, a high-minded dream of family, friends, and community. Onteora was the brainchild of two industrious siblings, Candace Thurber Wheeler (Fig. 4) and her youngest brother, Francis Beattie Thurber (1842–1907). To them, the Catskills represented their own roots (both were born in Delhi, New York), but also the inspiration for the first great movement in American art, the Hudson River school painters, many of whom they knew personally. The catalyst for their venture was the post–Civil War expansion in railroads, which by the 1880s had crept up the mountains to the nearby towns of Phoenicia and Tannersville. What had been an arduous ten-hour journey by boat up the Hudson, then by wagon into the mountains, was now halved. Five hours in a comfortable train carriage took you directly to the bottom of the hill upon which Onteora perched.

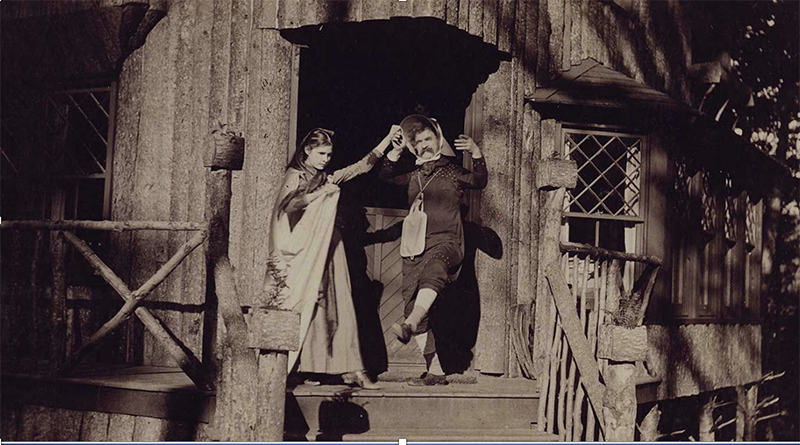

Fig. 5. A “steeplechase” at the Bear and Fox Inn in a photograph by C. O. Bickelmann (1855–1914), July 4, 1890. Silver gelatin print, 10 5/8 by 7 inches. The steeplechase of 1890, one of the earliest fancy dress affairs organized by Candace Wheeler, drew a happy crowd to watch Dunham Wheeler (1861–1938), Laurence Hutton (1843–1904), and others dressed as jockeys run races in front of the inn. Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain; 1835–1910) acted as the starter. Onteora Library, Tannersville, New York, E. Davis Gaillard Archive.

Wheeler is widely recognized as a pioneer in American decorative arts. She was a champion of women who needed to earn a living, providing applied-art training through her Society of Decorative Art, founded in 1877, and an exchange to sell women’s handiwork that debuted two years later. Wheeler also opened the first all-women interior design company, the Associated Artists (1883–1907). This was the successor to the first design firm of that name, which operated from 1879 to 1883 under a quartet of principals that included Wheeler, Louis Comfort Tiffany, painter Samuel Colman, and Lockwood de Forest, an artist and promoter of East Indian decorative arts. In 1893 her career peaked when she organized the interior decor of the Woman’s Building at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. But of all her initiatives, Onteora was closest to her heart, involving as it did a blend of family, friends, and pleasant design work.

Her brother Frank Thurber was no slouch, either. He and older brother Horace ran H. K. and F. B. Thurber and Company, a multi-million-dollar wholesale grocery concern. Founded in 1857, the company had headquarters on Broadway in New York that took up an entire city block, and offices in London and France. The company’s mainstay, among the thousands of products they sold, was a line of newly popular tinned goods. Mass production of tin cans beginning in 1880 made this possible, while attractive trade cards and can labels also contributed to the company’s success. It was Frank Thurber’s fortune that bankrolled Onteora, while Wheeler provided design inspiration and style. It was her dream of a simple summer life based on her own memories of childhood that set the genius loci of the place. Thurber’s wife, Jeannette Meyer (1850–1946), founder of the National Conservatory of Music, contributed the name Onteora. She attracted notable musicians and divas such as Louise Homer, a contralto who sang with Enrico Caruso, to the mountaintop.

Fig. 8. Reid designed this studio for artist Elizabeth Wentworth Roberts (1871–1927) c. 1900.

In the spring of 1883 the siblings set out by rail to find a spot on which they could build cottages. Stopping for the night in Tannersville, they hiked up the hill the following morning. While Wheeler rested on a rocky outcrop, her brother wandered away to find Thomas Convery, the farmer who owned the 108-acre property. Thurber bought it on the spot, appreciative of the rugged scenery but also of the land’s potential for development. That summer, the siblings built two houses close upon each other, and for the next five years they nested, inviting friends to come and camp or stay. In Wheeler’s small cottage, Pennyroyal, her daughter Dora sketched guests’ portraits on the plaster wall; the one of Samuel Clemens in profile is still there, visible through a hole in the grasscloth wall covering that has been surrounded by a frame and matting (Fig. 30). The Thurber cottage was a more substantial log cabin named Lotus Land. It burned to the ground in 1943.

But this busy pair could take only so much rest and relaxation. Having incorporated the Catskill Mountains Camp and Cottage Company the previous year, in 1888 Thurber bought the adjacent 458-acre Parker farm, partnering with his brother-inlaw Thomas Wheeler (1818–1895), his friend Samuel Coykendall, president of the Ulster and Delaware Railroad, and the latter’s son-in-law Henry Martin. Thurber’s architect nephew Dunham Wheeler (1861–1938) drafted plans for an inn, the Bear and Fox (Fig. 5), and three cottages, while Wheeler’s Associated Artists provided the upholstered furnishings. Dora painted the inn sign depicting a bear and fox dancing by the light of the moon. Simple furniture came from a local factory, Lockwood and Baldwin, in nearby Hunter, New York. A young visitor in 1892, Maud Appleton McDowell, remembered the inn as a “very primitive, simple bark building with partitions so thin that Mark Twain once said: ‘You could hear a man in the next room change his mind.’ These walls were made of burlap stretched across the studdings and a hatpin (we wore such things in those days) could be stuck through from one room to the other, for I tried it one day.”1

Candace Wheeler laid out the roads and hiking trails with the help of Calvert Vaux, best known as the co-designer of New York City’s Central Park and Brooklyn’s Prospect Park. Vaux’s Ramble in Central Park was inspired by the mountains of upstate New York; it was happy work for him to design the layout of the Thurber-Wheeler rustic colony. His name appears on the Cottage Company’s letterhead as “Consulting Landscape Architect” (Fig. 14). Now all that remained was for the Cottage Company to market the resort.

What began in 1888 with general advertisements for a healthy, simple mountain getaway from the summer heat of New York City soon became something more exclusive and distinct. Newport had its yachtsmen and the coast of Maine was dotted with old-money enclaves, but Onteora’s inhabitants were a crowd of Amazons and literary lions. Many of those who flocked there were, like Wheeler, successful professional women in the arts. Mary Mapes Dodge, author of Hans Brinker: or, The Silver Skates and founder-editor of St. Nicholas Magazine, built two cottages. General George Custer’s widow, Libbie, who re-made her husband’s reputation through memoirs and lectures, christened her cottage The Flags, after the regimental banners that hung over her fireplace (Figs. 22, 23). Ruth McEnery Stuart, a popular southern writer; Sarah Woolsey, who, under the pen name Susan Coolidge, wrote the What Katy Did children’s book series; Mariana Griswold (Mrs. Schuyler) Van Rensselaer, critic and first biographer of architect H. H. Richardson; Jeannette Gilder, playwright and editor of Critic magazine; and Lucia Gilbert Runkle (1844–1927), the first woman to write leaders for the New-York Tribune and later an editor at Harper and Brothers, all bought or built in Onteora. There were educators as well: Maria Kimball taught elocution at Vassar and Brearley and Ellen Churchill Semple lectured on geography at the University of Chicago.

Who were the men of Onteora? In the early days it seemed as if the entire staffs of Harper’s and the Century magazines took up residence. The poet and editor Richard Watson Gilder and his wife, artist Helena de Kay came, as did Frank Stockton, author of the short story “The Lady, Or The Tiger?” and Laurence Hutton, critic and essayist. John Burroughs, the nature writer, who lived nearby in Roxbury, was a frequent visitor. During World War I, Hamlin Garland, who later won the Pulitzer Prize for biography, brought his family to the mountaintop. There were medical men: Custer’s senior army surgeon James P. Kimball built, as did society doctor William B. Wood, who brought his star patient, actress Maude Adams (the first American Peter Pan), to Onteora to strengthen her lungs with mountain air. There were lawyers and businessmen, chiefly friends and associates of Frank Thurber; and a bumper crop of professors, from Brander Matthews and Cornelius Rybner of Columbia to Arthur Kingsley Porter of Harvard.

Literary types were thick on the ground, but none as famous as Samuel Clemens, who visited with his family on several occasions and rented Balsam Cottage across from the inn in 1890 (Fig. 15). What a coup this was for Wheeler, who, in her autobiography, Yesterdays In a Busy Life, devoted an entire chapter to her friendship with Clemens, whose home in West Hartford, Connecticut, she had helped decorate in the early 1880s. Now the Mark Twain House and Museum, it is a rare intact example of the first Associated Artists’ design work. Clemens, who was not above poking fun at Wheeler’s high-flown intellectual coterie, told this anecdote about the local farmers’ response to the Onteorans:

The resorters were a puzzle to them, their ways were so strange and their interests so trivial. They drove the resorters over the mountain roads and listened in shamed surprise at their bursts of enthusiasm over the scenery. The farmers had had that scenery on exhibition from their mountain roosts all their lives, and had never noticed anything remarkable about it. By way of an incident: a pair of these primitives were overheard chatting about the resorters, one day, and in the course of their talk this remark was dropped: “I was a-drivin’ a passel of ’em round about yisterday evenin’, quiet ones, you know, still and solemn, and all to wunst they busted out to make your hair lift and I judged hell was to pay. Now what do you reckon it was? It wa’n’t anything but jest one of them common damned yaller sunsets.” 2

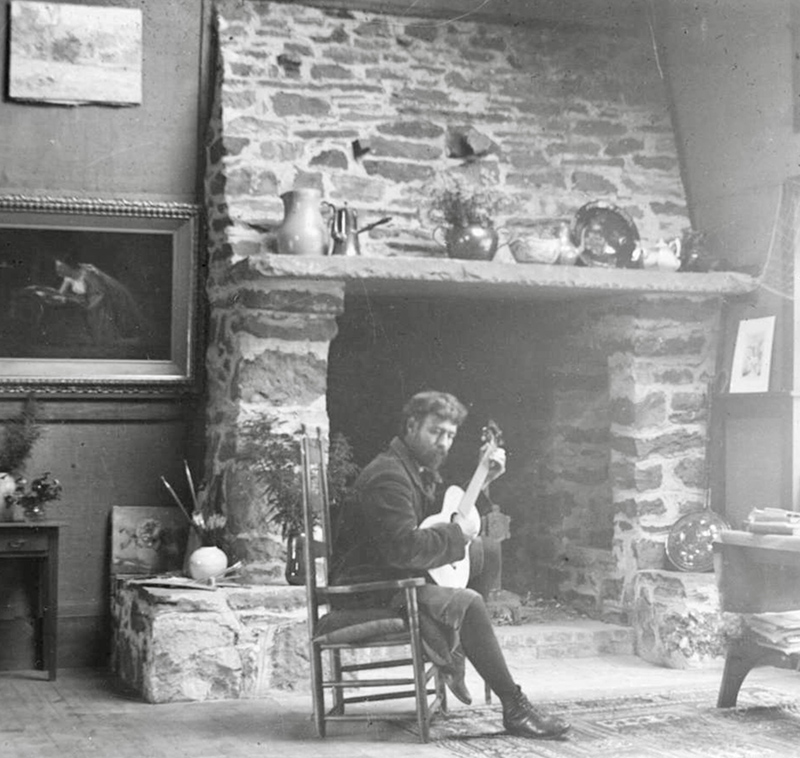

James Carroll Beckwith (1852–1917), one of the earliest cottage builders, was perhaps the best known of Onteora’s artists, but there were enough so that the colony developed a reputation as an artists’ retreat. John White Alexander built his studio just down the hill from Beckwith’s, while Edwin Howland Blashfield and Albert Herter rented cottages. George Bellows spent a summer in Onteora in 1912, executing ten paintings during his stay. He exhibited one of these, Evening Glow, at the 1913 Armory Show. Beckwith and the Canadian painter and architect George Agnew Reid both held summer schools in Onteora for a number of years. The pupils were young women who wished to study painting without the expense of a European sojourn. American impressionists Clara McChesney and Elizabeth Wentworth Roberts both cut their teeth learning to paint there. Beckwith detested the work, but it paid the bills.

The Thurbers and Wheelers may have founded Onteora, but it was Reid who shaped the community for the new century. He and his wife, Mary Hiester (1854–1921), a painter he met in Thomas Eakins’s drawing class at the Pennsylvania Academy, came from Toronto to the mountaintop in the summer of 1891. Reid, who habitually wore a bright red tam-o’-shanter, built his cottage down the hill toward Tannersville. Bonnie Brae, as he dubbed it, was a charming, English-inflected arts and crafts bungalow with tonalist murals (Fig. 28), and it made Dunham Wheeler’s stick-style cottages, cheaply built and with smoky chimneys, look primitive and old-fashioned. Reid earned Wheeler’s displeasure beginning in 1894, when the commission for Onteora’s church, All Souls, went not to Dunham but to him (Figs. 24, 25). When it was enlarged in 1910, Reid designed some of the stained glass and painted angel murals in the apse. At the rear, over a fireplace, Dora Wheeler painted a memorial to her father, Thomas Wheeler, who died in 1895: a glance back and forth tells exactly why Reid’s art prevailed. In all, Reid got the commissions for about twenty cottages, as well as two churches and the library. Design in Onteora was no longer Candace Wheeler’s sole domain: others had begun to craft a different kind of community. She wrote disparagingly in her autobiography of this second phase in the life of Onteora, where new “people came and brought their down cushions with them.” 3

The divide between resorters and the Camp and Cottage Company was inevitable. The former, who in 1895 created an association to address issues of sanitation, road maintenance, and water supply, found themselves in opposition to the company, whose focus was land and cottage sales. During summer droughts, water had to be carted up from Tannersville in barrels and delivered on horse-drawn sledges to each cottage. There was no sewer or water system, and the original cottages had no cooking amenities. Meals were to be had at the Bear and Fox Inn, but cottagers soon realized the inconvenience of this and built themselves add-on kitchens. Wheeler’s ideal of summer life was closer to camping than it was to the comforts of home. At Pennyroyal, she had no kitchen—she cooked outside in a lean-to shed. Most did not see eye to eye with her on the subject.

Then in the financial panic of 1893, the Thurber grocery firm went bankrupt. Frank Thurber’s remaining asset was his land in Onteora. This he sold to his wealthy friends to keep afloat, but they were the down-cushion types, and by 1903 they had wrested control of the community from the Cottage Company, which was dissolved. The Onteora Club organized in its place as a stock corporation, as it remains to this day. Reid became the club’s managing director and oversaw the installation of the first water system. Wheeler wanted nothing to do with this new state of affairs. She even considered starting another community in keeping with her rustic vision, but at age seventy-six, it was beyond her power. Her brother, a realist, remained an important figure in the new club governance until his death in 1907.

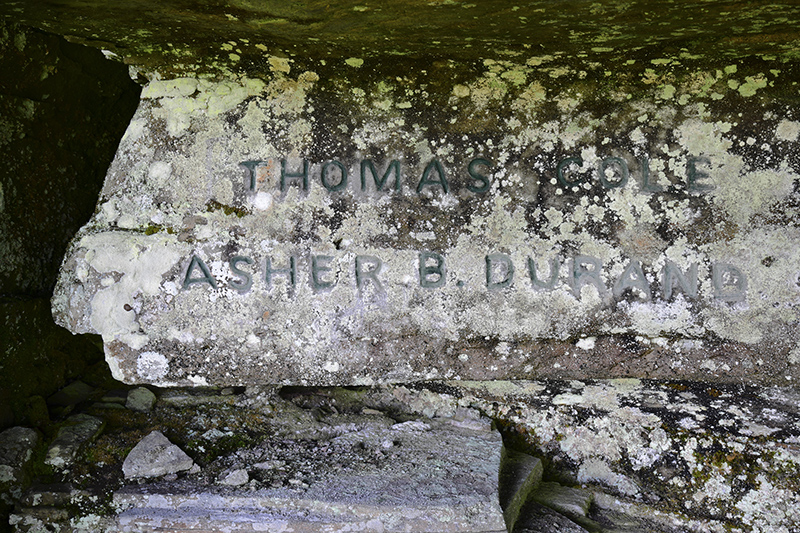

Divisive issues aside, Onteorans came to the mountaintop to relax and have fun. There was always an event on the Fourth of July—a dance, or a steeplechase with jockeys on hobbyhorses racing in front of the inn. Wheeler loved to produce pageants, with everyone draped in cheesecloth or portieres to represent classical figures and harvest tableaux. In 1896 she superintended a procession to the top of Onteora Mountain, where, in a shallow cave, she had built a stone bench over which the names of her friends among the Hudson River painters were carved (Fig. 9). She christened it Artist’s Rock.

Fond of pageantry and costume as Onteorans were, it was not long before small theaters began to pop up. Maude Adams had an outdoor amphitheater on her property, Kiskadden, and she invited the children of Onteora to take part in plays (she gave each child a silver charm to commemorate their participation). Her 1905 Peter Pan costume was designed by her neighbor, the painter John White Alexander, and sewn by his wife. Adams was painted wearing her Peter Pan outfit, standing at the Artist’s Rock the following year by Sigismund Ivanowski. Other cottages also made room for dramatic productions. Ben Ali Haggin (1882–1951), society portraitist and partner in Florenz Ziegfeld’s Follies, produced an elaborate pantomime, “In A Convent Garden,” at his mother’s Wildmuir Cottage in 1922. In 1926 Edward H. Jones paid for a proper, dedicated theater. It opened the following year with Rip Van Winkle, and plays, both for adults and children, have been a feature of Onteora summers ever since.

Even artists and writers need exercise, and there was no lack of opportunity for hiking either on the club property or the wider mountain landscape. A nearby stable had horses and carriages for rent and there was a tennis court in front of the inn. In 1896 a six-hole golf course stood just below the church—ten years later it was moved and expanded on the neighboring Mattice farm, which the Camp and Cottage Company had bought in 1900. The farmhouse became a sports center, replaced in 1940 by the current field house, and four tennis courts were put in. Bill Tilden, the American tennis great, learned the game as a child on Onteora’s clay courts. In 1924 a pool was added to the field house amenities, and just before the Depression began, the Mattice farm swamp was drained, dammed, and dredged to make a small lake. What is left of Wheeler’s original vision? Many of her small, simple cottages have grown out of all recognition. A kitchen, a new porch, a wing added over time meant that original buildings have been swallowed up in additions. Most retain some of their rustic charm, however, with bark slab siding, decorative shingle courses, Dutch doors, interior birch bannisters, and porches with spectacular views. The early Associated Artists cottages are easy to spot: they’re smaller, with floors that slump down the mountain; board-and-bead siding with a dado of painted burlap or Japanese grass cloth; and large, smoky fireplaces that throw no heat. In contrast, Reid’s arts and crafts cottages are larger, have proper foundations and fireplaces that work well, and some have furniture designed by the architect.

The winding roads and woodland trails that Wheeler designed with Vaux are still there, and Wheeler’s sense of community still thrives. The fairs, smaller in scale, take place at the library every summer, and the theater is a locus for children and adults. While the Bear and Fox Inn closed in 1960, the field house now serves meals and provides accommodation. It also houses the club’s collection of paintings by resident artists. All Souls Church is open to all comers, and is a favorite spot for weddings. Surely Wheeler would approve of the Mountaintop Arboretum, founded in 1977 by Peter and Bonnie Ahrens as a sanctuary devoted to the cultivation of native and exotic species that offers diverse educational programming on 178 acres. In her autobiography, Wheeler wrote that Onteora “grew by an accident of friendship, the human instinct for congenial companionship, the desire to draw people whom we loved into an almost unknown realm of beauty. . . . where we could build a camp or cabin and live the wild life for a little space.”4 Her words still ring true today.

Fig. 30. A sketch of Clemens by Dora Wheeler (1856–1940), c. 1886, can be seen on the living room wall at Pennyroyal.

1 Maud Appleton McDowell, The Joy of Memories (privately printed, 1937), p. 29. 2 Mark Twain, “Chapters from My Autobiography, VIII,” North American Review, vol. 186, no. 624 (November 1907), pp. 327–328. 3 Candace Wheeler, Yesterdays in a Busy Life (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1918), p. 323. 4 Ibid., pp. 287, 268.

JANE CURLEY is an independent curator specializing in children’s literature, who works frequently with the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art. She earned a PhD in art history from Yale University. Her summers are spent in Onteora, where she lives in a crooked Associated Artists’ cottage. She has been the club historian for many years.