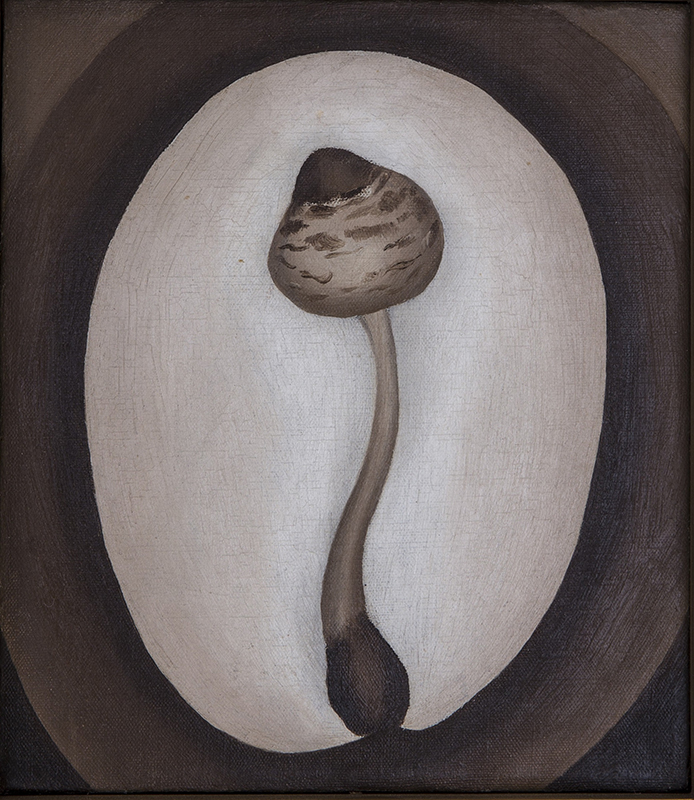

Fig. 1. Whirl of Life by Ida Ten Eyck O’Keeffe (1889–1961), 1936. Oil on canvas, 36 by 25 7/8 inches. Collection of Paul and Sherlea Taylor. Except as noted, all photographs © 2018 Dallas Museum of Art.

Georgia O’Keeffe looms over American art of the twentieth century, her fame subsuming those who traveled in her life’s orbit. Because she outlived nearly all her family and friends, she shaped her story and the roles of others in it without fear of challenge. And so she did with her younger sister, Ida Ten Eyck O’Keeffe, whose artistic talent was sufficiently threatening to compel Georgia to malign her sister’s gifts for posterity by portraying her as a minor talent unworthy of serious consideration.

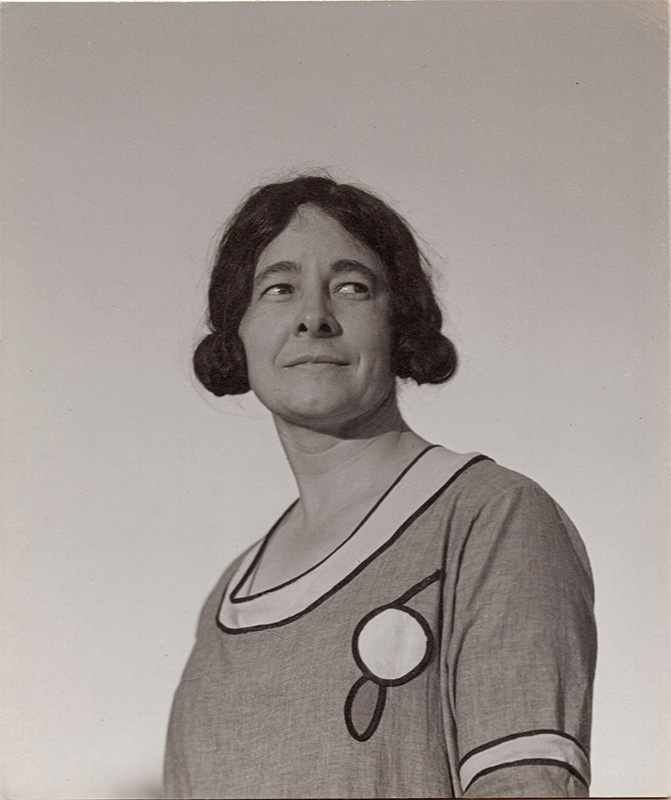

Fig. 2. A portrait of O’Keeffe by Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946), 1924. Gelatin silver print, 4¼ by 3½ inches. Collection of Michael Stipe.

From their earliest art lessons in Wisconsin to the classrooms of Chatham Episcopal Institute (today Chatham Hall) and the University of Virginia’s summer sessions in Charlottesville, the sisters studied with the same teachers, thereby sharing the same pedagogic roots. (Interestingly, in those early years the family thought Ida possessed the greater talent.) In the 1910s, both sisters taught art at a succession of schools in the South. And, in 1918, both sisters arrived in New York City—Georgia having been plucked from her teaching position in Canyon, Texas, by Alfred Stieglitz, and Ida entering the three-year nursing program at Mount Sinai Hospital.

Fig. 3. Variation on a Lighthouse Theme II, c. 1931–1932. Oil on canvas, 20 by 14 inches. Private collection.

Beyond the juvenilia of her three years at Chatham, no works by Ida survive from her years of teaching in the 1910s. Her earliest works as a serious artist emerged during an extended private nursing assignment in the home of the Stoeckel family in 1925 in Norfolk, Connecticut. Inspired by the work of James Abbott McNeill Whistler in the Stoeckels’ library and the natural setting of their vast property, she created several of her first paintings. Her correspondence with Alfred Stieglitz at this time reveals that, in spite of all of her prior training and work as an art instructor, she had never received instruction in oil painting—a situation typical in the education of young women presumably destined to become wives and mothers. Oil painting was considered the purview of professionals, who, at that time, were assumed to be male.

Fig. 4. Creation, c. 1936. Signed “Ida O’Keeffe” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 23 by 28 inches. Photograph courtesy of the Gerald Peters Gallery, Santa Fe.

Even though she was a newcomer to the medium, Ida progressed by trial and error, frequently seeking advice from Georgia. She persisted, making quick progress, and by 1926, Stieglitz wrote to a friend that her work showed “incredible talent.”1 In late 1927 she was included in an exhibition curated by Georgia for the Opportunity Gallery and, seeking not to be perceived as riding her sister’s coattails, she exhibited under the name of “Ida Ten Eyck.” One of the five paintings shown was Still Life (Fig. 10). Painted at Lake George during the summer of 1926, the work possesses naive charm and reveals, as well, a debt to Whistler in the composition of space that clearly follows his Arrangement in Grey and Black: Portrait of the Artist’s Mother No. 1 (1871).

Fig. 5. Star Gazing in Texas, 1938. Inscribed “Ida TenEyck O’Keeffe/ Spring Lethargy, Texas/ 1938” on the back. Oil on canvas, 27 ¾ by 33 ¾ inches (framed). Dallas Museum of Art, general acquisitions fund and Janet Kendall Forsythe Fund in honor of Janet Kendall Forsythe on behalf of the Earl A. Forsythe family.

The positive critical response Ida received compelled her to pursue formal training, and in the fall of 1929 she entered the Teachers College of Columbia University, completing both bachelor’s and master’s degrees in fine art. The experience was transformative for her art, and key to that metamorphosis was the tutelage of Charles James Martin, with whom Georgia had also studied in 1914. He emphasized essence and interpretation over representation and helped Ida, as he had Georgia, to adopt dynamic and abstracted interpretations of visual phenomena. His impact is clearest in Ida’s series based on the Highland Light at North Truro on Cape Cod, in which she employs forceful compositional devices, including that of Dynamic Symmetry, a methodology that derives from the Fibonacci sequence that was widely practiced at the time (Figs. 3, 11).

Fig. 6. Portrait of a Banana Tree, c. 1946. Signed “Ida Ten Eyck O’Keeffe” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 30 by 35 inches. Collection of Elizabeth Behrens Ellis; photograph by Rebecca Vera-Martinez.

Variation on a Lighthouse Theme VII, and Toad Stool (Fig. 7)—created in Tennessee during the summer of 1932— find parallels in the work of artists of the Stieglitz circle, with which Ida would have been most familiar. The diagonal beams streaming from her lighthouse perform the same compositional function as the “lines of force” observed in Charles Demuth’s My Egypt, a precisionist work exhibited with Stieglitz in 1930. Similarly, the nesting ovals of Toad Stool find resonance with the organic circular forms of Arthur Dove’s works, such as Silver Sun (1929; Art Institute of Chicago).

Fig. 7. Toad Stool, 1932. Oil on canvas, 8 by 7 inches.

Ida’s Highland Lighthouse series and works from Tennessee debuted in New York City in March of 1933 at the Delphic Studios. The previous month, Catherine O’Keeffe Klenert, the fourth of the five sisters, had also exhibited there and, Georgia, resenting her sister exhibiting on what she saw as her turf, demanded that they cease doing so. While Catherine gave up painting altogether, Ida’s refusal to do so ultimately drove a wedge between her and Georgia. The sisters, though once close, became estranged and remained so for the rest of their lives.

Fig. 8. Young Banana Plant, 1939. Signed “Ida Ten Eyck O’Keeffe” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 14 by 9 inches. Collection of Judge B. Michael Chitty and Elise Chitty.

Ida O’Keeffe launched her career as an artist against the backdrop of the Great Depression. Single and self-supporting, she found it necessary to supplement her income by doing research for businesses, writing short stories and educational materials, and executing a mural under the Public Works of Art Project. Focusing fully on her own work was a luxury she would never be able to afford.

Fig. 9. Ozark Lime Kiln, 1938. Signed “Ida Ten Eyck O’Keeffe” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 22 by 26 1/4 inches. Collection of Kelly Kissel.

In the fall of 1934 Ida accepted the first in a succession of temporary teaching positions, which required her repeated relocation. She took jobs along the East Coast, in the Midwest and in the South—a scenario that mirrored Georgia’s peregrinations before her rescue by Stieglitz in 1918. The demands of those positions left little time for Ida to develop a stylistically cohesive body of work and her exhibitions of the late 1930s juxtapose abstract works such as Creation (Fig. 4) and Whirl of Life (Fig. 1) against Regionalist-inspired works like Ozark Lime Kiln (Fig. 9) and Star Gazing in Texas (Fig. 5). In this mix, as well, were realistic works such as Young Banana Plant (Fig. 8), created during a visit to Cuba.

Fig. 10. Still Life (Still Life with Fruit), 1926. Oil on canvas, 20 by 16 inches. Peters Family Art Foundation; photograph courtesy of Gerald Peters Gallery.

After moving thirteen times in ten years, Ida’s nomadic existence came to an end when she settled in Whittier, California, in the early 1940s. Stylistically, her work returned to realistic representation in still lifes, landscapes, and works such as Portrait of a Banana Tree (Fig. 6). Although she never exhibited in New York again, she became an active and valued member of the Whittier arts community, teaching and exhibiting there and at other venues around Southern California until her death in 1961. Georgia, as if forgetting her culpability in obstructing her sister’s professional ambitions, would muse that Ida’s was “in some odd way . . . a wasted life.”2 Now, thanks to the exhibition Ida O’Keeffe: Escaping Georgia’s Shadow, Georgia’s will no longer be the final word on Ida and her life and work.

Fig. 11. Variation on a Lighthouse Theme VII, c. 1931– 1932. Signed “IDA O’KEEFFE” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 26 1/8 by 20 ¼ inches. University of California, Irvine, Institute and Museum for California Art, Buck Collection; Vera-Martinez photograph.

The exhibition Ida O’Keeffe: Escaping Georgia’s Shadow, organized by Sue Canterbury and on view at the Dallas Museum of Art to February 24, 2019, is accompanied by a scholarly catalogue of the same title, published by the museum and distributed by Yale University Press.

SUE CANTERBURY is the Pauline Gill Sullivan Associate Curator of American Art at the Dallas Museum of Art.

1 New York Sun, April 27, 1940, clipping, Ida O’Keeffe Papers, University of Oregon. 2 Georgia O’Keeffe to Claudia O’Keeffe, January 24, 1961, Archives of American Art, reel 4,390.