In the early twentieth century, the town of Woodstock, New York, in the lee of the Catskill Mountains, evolved into one of the leading art colonies in the United States. Traditional, modern, and experimental artistic styles were practiced there. Painters ranged from exponents of the evocative and moody tonalist landscape aesthetic that came into vogue around 1900, to the gestural and emotional abstract expressionists, who exploded to global acclaim in the 1950s. Woodstock was also home to an active community of decorative artists, an outgrowth of the establishment in 1902 of the Byrdcliffe arts and crafts colony on a mountainside overlooking the village. An astounding roster of America’s leading artists thrived for decades in Woodstock, as full-time residents or summertime migrants, typically from New York City, about a hundred miles south. They included George Bellows, Birge Harrison, John F. Carlson, Eugene Speicher, Andrew Dasburg, Alexander Archipenko, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Bradley Walker Tomlin, and Philip Guston—in short, many of the important contributors to the development of American art during the last century.

One thing Woodstock lacked in the early years was a place for artists to show their work to the public. This year marks the one hundredth anniversary of the founding of the Woodstock Art Association, the forebear of what is today the Woodstock Artists Association and Museum. In September 1919 Dasburg announced that he and fellow painter Henry Lee McFee would form a gallery exhibition space in Woodstock. They were soon joined in the effort by Carlson and artists Frank Swift Chase and Carl Eric Lindin. Certificates of stock were sold to interested parties—two hundred shares were offered at $50 apiece to raise $10,000 to erect a gallery. The long and low-slung colonial revival building, designed by the unfortunately named New York architect William Alciphron Boring, was completed in 1921 (Fig. 11), and exhibitions there attracted the steady attention of local and national press. Thanks to a bequest from the artist Dorothy Varian and contributions from stockbroker Belmont Towbin and his wife, artist Phoebe Towbin, an expansion was completed in 1992, providing a space for historical exhibitions, drawn primarily from the museum’s permanent collection.

The formation of that collection can be credited to an energetic and resourceful group of artists and art lovers, who, in the late 1960s and early 1970s, realized the importance of ensuring that future generations would have the opportunity to study the achievements of the creative talents who have made their home in this Catskill community of New York State. The association made its first acquisitions in 1973, and in the course of nearly a half-century the institution has built an exemplary collection of more than two thousand paintings, drawings, watercolors, prints, and sculptures, as well as items of furniture, ceramics, and other works of decorative art. These have come to the association principally through the donations of artists and their descendants as well as from local collectors and townspeople. In celebration of its one hundredth anniversary, the association has published a new volume on the permanent collection—the first in more than thirty years. A discussion of some of the paintings featured in this new publication illuminates some of the colony’s fascinating history and artistic achievements.

The Woodstock School of Landscape Painting was in operation from 1906 to 1922 under the auspices of the Art Students League in New York City. In 1911 Birge Harrison relinquished his position as head of the school to his former pupil and assistant John Carlson, who, in turn, hired his own former student Frank Chase as his assistant. Chase specialized in painting the streams, trees, and mountains of the region, and preferred picturing the seasons of autumn and winter (Fig. 3). Like Harrison he often found his subjects among the “houses of the little village itself, seen from the flat meadows.”1 During his early years in Woodstock Chase practiced Harrison’s tonalist mode of landscape painting and paid special attention to the subtlest of tone separations.

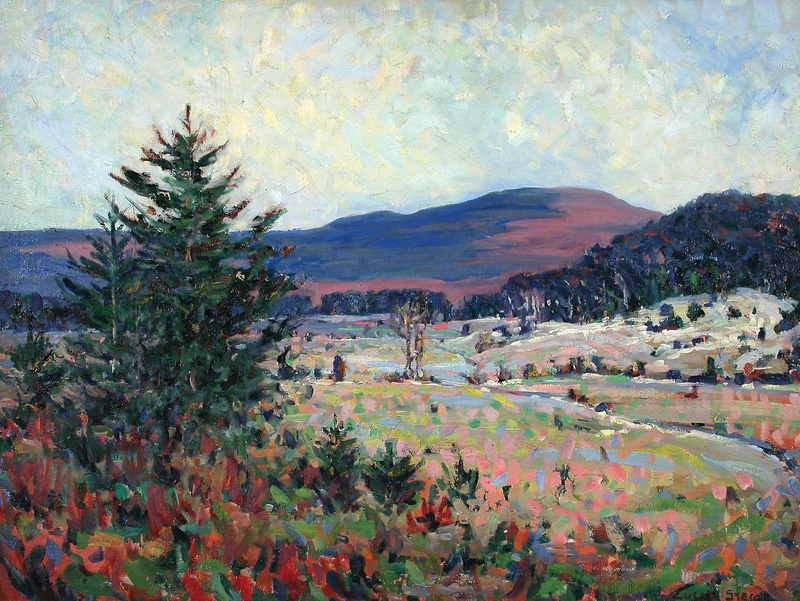

Zulma Steele trained as a landscape painter in Woodstock with Harrison, and her earliest landscapes reflect his influence. In about 1910 she adopted a more modern and impressionistic approach, and within a few years was creating landscapes (Fig. 5) featuring bold, pure colors, simplified shapes, and strong rhythmic patterning, which harken back in spirit to Arthur Wesley Dow, her former teacher at Pratt Institute. Occasionally, Steele applied paint in tiny dot-like strokes, recalling the pointillist canvases of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac.

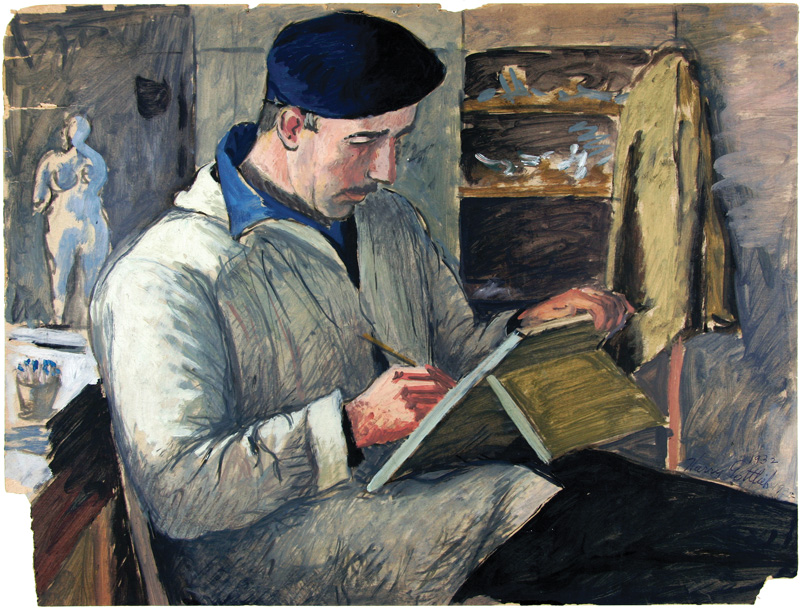

Andrew Dasburg had a major impact on the Woodstock art colony in the early decades of the twentieth century. From 1906 to 1908 he studied with Harrison; in the spring of 1909 he traveled to Paris, where he became aware of the newest developments in art, and in the years ahead began to work under the influence of Paul Cézanne and the cubists. In 1910 Dasburg returned to Woodstock, and over the course of the next few years he and his fellow modernists Henry Lee McFee and Konrad Cramer formed a tight artistic circle and met regularly to look at and discuss one another’s work. A few months after the closing of the Armory Show in 1913, Dasburg traveled to Monhegan Island in Maine (Fig. 4). There he painted alongside George Bellows, Leon Kroll, Randall Davey, and others. At this time he fell fully under the spell of Cézanne influence, applying thick block-shaped brushstrokes using a forceful, cutting, and thrusting motion—taking Cézanne’s beloved Provence out to sea.

McFee traveled to Woodstock to study with Harrison in the summers of 1909 and 1910. Delighted with country life and the companionship of fellow artists, he stayed on. In around 1912 he came to the realization that his paintings “were plastic, and the more I simplified, the more did I achieve a unit, or the promise of one. Space, I began to see, could be as important as the thing itself, if it was shaped, modeled, realized as thoroughly as the object. This very naturally led to an interest in Cubism.”2 The earliest cubist paintings by McFee that have surfaced date from 1915. Over the next decade he placed faceted glass bowls and vases on tables at the center of his still-life compositions (Fig. 6) so that their edges appear to dissolve into the surrounding space and the other assorted objects around them, while augmenting the neutral colors of analytic cubism with hues of gold, rose, and pale blue.

Throughout his life the German-born Konrad Cramer was open to working in new techniques, styles, and mediums. Barns and Corner Porch of 1922 (Fig. 2) is made up of a combination of oil paint and collage (a glued-on photograph of leaves at left of center and a piece of corrugated cardboard painted red at far right of center). The artist transplants the synthetic cubist paintings and collages of Braque and Picasso to a rural American setting. Cramer’s work may partly have been created in response to Max Weber’s iconic painting Chinese Restaurant (1915, Whitney Museum of American Art), turning that urban subject on its head.

Charles Rosen initially came to Woodstock to teach landscape painting in 1918, following Carlson’s resignation from the Art Students League’s summer school. Two years later Rosen left New Hope, Pennsylvania, and settled in Woodstock. Sometime around 1923 he built a house next door to the residences of his close friends Eugene Speicher and George Bellows. Under the influence of Dasburg, Rosen now turned to Cézanne as his guiding light. In his works (Fig. 8) Rosen shows a greater concern for geometry and the intricate play of geometric forms, and a new interest in stressing independent rhythmic patterns. He abandoned the frequently brilliant and varied palette of his impressionistic New Hope landscapes, but in time incorporated deeper and more decorative or ornamental shades of red, blue, green, and yellow.

Yasuo Kuniyoshi first came to Woodstock in 1917, when he took a landscape painting course at the league’s summer school with Carlson. Eventually he and his wife, the artist Katherine Schmidt, built a modest house on a hillside property on Ohayo Mountain Road. In his landscapes of the early 1920s (Fig. 7) Kuniyoshi worked primarily from imagination and memory, favored a flattened perspective, and placed elements on an upright-oriented plane. By then he had come under the influence of American folk art, initially inspired in this direction by the collector and art writer Hamilton Easter Field. His landscapes of the time continue to show the influence of the feathery impressionist brushwork of Renoir.

The Woodstock Artists Association used the purchase funds generated by the bequest of Karl E. Fortess in 1993 to acquire Doris Lee’s folk-art inspired likeness of Cecile Forman (Fig. 13), a woman known for her stylish dress who first received recognition as an artist for her charcoal portraits of film stars, which were featured in the Brooklyn Eagle, New York Sun, and Brooklyn Times-Union in the mid-1930s. Forman studied at the Art Students League and, later, at the Woodstock summer school with Kuniyoshi and Arnold Blanch. There, she became great friends with Doris Lee, with whom she was in touch on a daily basis for years after moving to the town. Between 1978 and 1984, she gave works to the association’s collection by Speicher, Arnold Blanch, Stuart Edie, Sydney Laufman, and Fletcher Martin.

Visual artists began to settle in the Maverick art colony in nearby West Hurley, New York, following the end of World War I. The initial settlers there were musicians, writers, and philosophers. In the fall of 1921 Harry Gottlieb went to Maverick on the advice of a friend after he managed to save enough money to be free for a whole summer to paint. Maverick founder Hervey White agreed to rent him one of the cottages on a year-round basis if he brought in other couples, with the promise that White would charge the couples only $100 a year to rent one of the colony’s simple, almost primitive structures.

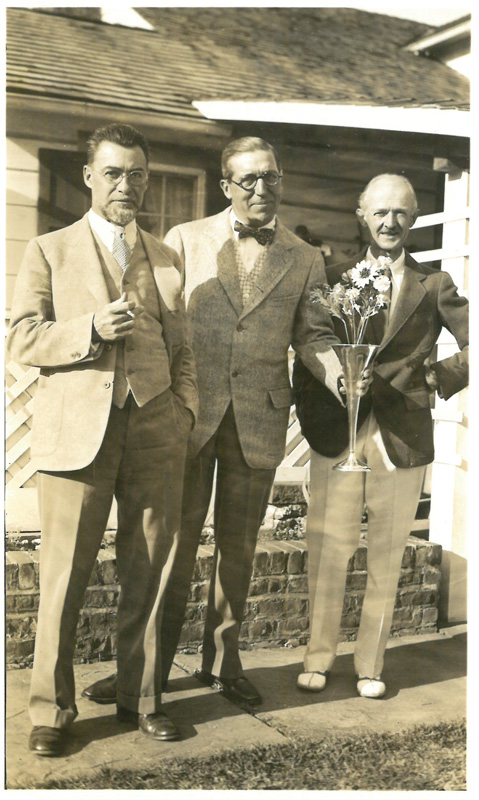

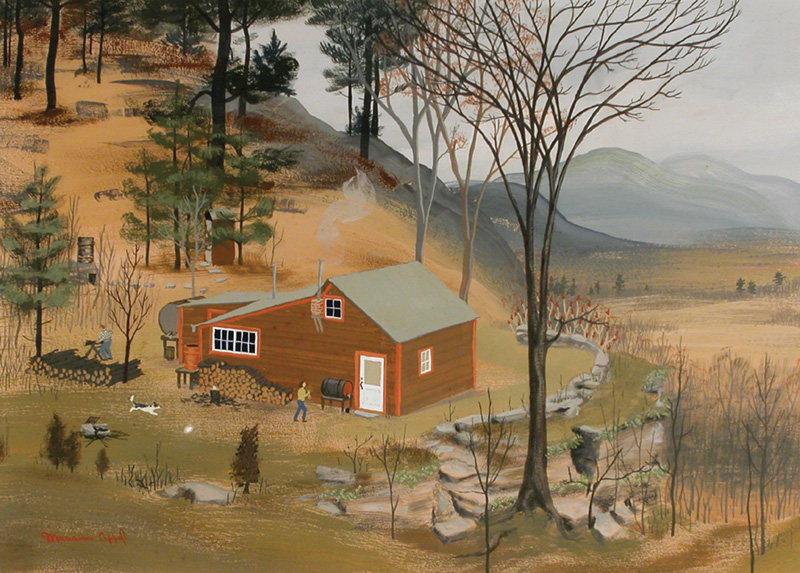

Gottlieb convinced his former fellow students at the Minneapolis School of Art and the Art Students League John B. Flannagan, Hannah Small and Austin Mecklem, and Arnold and Lucille Blanch to join him and his wife, artist Eugenie Gershoy. Mecklem’s house is featured in a painting by his second wife, Marianne Appel (Fig. 12), whose flat, reductive style, with its absence of cast shadows, is a perfect metaphor for the stark basic living conditions experienced by the pioneering settlers at Maverick. In 1932 Gottlieb painted a portrait in gouache of Carl Walters (Fig. 14), who became one of the most beloved artists to work in the art colony. Walters was part of the wave of ceramic sculptors that developed in America in the 1920s that also included Henry Varnum Poor and Waylande Gregory.

In 1993 Karl Fortess donated three works to the Woodstock Artists Association by Philip Guston, who also was a longtime resident at Maverick. Fortess and Guston’s friendship was formed in part by their mutual ties to the art department at Boston University, where they both taught. My Coffee Cup (Fig. 1) reveals the radical change of direction in Guston’s art after he and his wife settled full-time in Woodstock in 1967, and the artist moved from abstraction to narrative figuration, often including objects found in his studio—cups of all kinds, cigarette butts, shoes, and books—coexisting with things that lived in his fantasy, such as the butterfly that sits on the rim of the coffee cup.

In recent years, the Woodstock Artists Association has become more proactive in its purchase of important twentieth-century works for the permanent collection. Among the recent acquisitions are a winter landscape by association co-founder Frank Chase (Fig. 3), a ceramic sculpture of a hippo by Walters, and a crayon drawing of a lion by Guston, all bought with the help of donors. In the future, the institution has hopes of escalating its purchasing activity, increasing its holdings of art by contemporaries, and further expanding its facility. It is anticipated that the new publication on the permanent collection will add to the education of the public and students of American art alike on the subject of this unique art colony’s glorious history, entice new and exciting gifts to the collection, add additional funds for acquisitions, and aid in increasing understanding of what has made Woodstock such a wonderful home for the arts for more than a century.

1 Birge Harrison, “Painting at Woodstock: The Work of a Group of American Landscape Painters,” Arts and Decoration, vol. 2, no. 7 (May 1912), p. 247. 2 Henry Lee McFee, “My Painting and Its Development,” Creative Art, vol. 4, no. 3 (March 1929), p. xxix.