She was an independent woman from the landed gentry who defied the stereotypes of her class and gender to become a celebrated artist. He was the most exciting and innovative ceramics designer of England’s Victorian age, who collaborated with William Morris to create beautiful interiors for wealthy clients.

Why haven’t Evelyn and William De Morgan become household names? Evelyn’s reputation has undoubtedly been sidelined by canonized male painters, and William’s ceramics have often been overlooked in an artistic hierarchy that favors painting. The exhibition A Marriage of Arts and Crafts: Evelyn and William De Morgan celebrates the life and work of these exceptional artists, reclaiming their rightful place at the center of the Victorian art world. Featuring more than seventy ceramics, paintings, and drawings of unique beauty, the exhibition offers a rare, comprehensive opportunity to experience the work of the De Morgans.

By the time William and Evelyn met in 1883, they were both well-established artists. Evelyn had been born to upper-class parents in London in 1855. Although they had old-fashioned ideals, Evelyn’s parents encouraged their daughter’s education. Her knowledge of the world and strong will led her to refuse her parents’ wishes to be presented as a debutante. Instead, she made the steadfast decision to become an artist. Her father seems to have been supportive of the decision, hiring a drawing tutor to train her. She was admitted to the newly established Slade School of Art at the University of London in January 1873, affording her an innovative art education that would shape her future.

The Slade had been established a few years prior to Evelyn’s admission with two clear objectives: to admit women on the same terms as men, and to instruct its pupils primarily in the study of the live model. Evelyn could be sure her work would be judged on merit and not overlooked because she was a woman. Winning a number of medals for drawing, composition, and painting, along with a full scholarship, she excelled at the Slade. As early as 1876, the same year she graduated, she was exhibiting her paintings and selling her works to notable lords and members of Parliament.

Evelyn’s early work was characterized by her desire to fit in. She made beautiful paintings that adhered to the demands of taste to secure buyers and compete with male artists. The key style her work can be associated with is the aesthetic movement, an artistic style and philosophy championed by Oscar Wilde and others that valued form over function and promoted the credo “art for art’s sake.” Helen of Troy exemplifies the style of the medievalist Pre-Raphaelite branch of the aesthetic movement (Fig. 2). Helen stands in the center admiring her own beauty surrounded by blooming roses and white doves; it is a picture that highlights the seductive power of beauty.

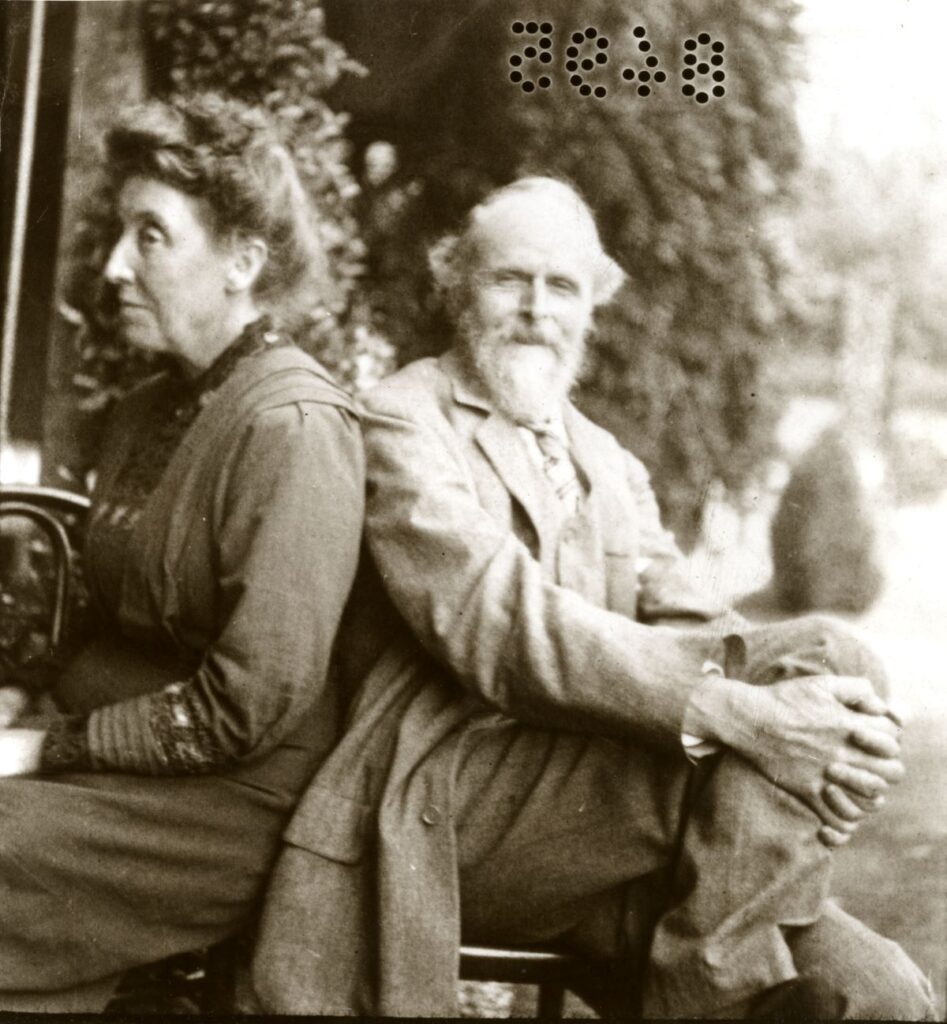

Evelyn exhibited in the most important avant-garde exhibitions of the period: at the Grosvenor Gallery and the New Gallery in London, and in other galleries across England. Her network of friends and patrons led her to become acquainted with the journalist Walter Bagehot, whose circle included the ceramics designer William De Morgan. In 1883, at a costume party hosted by Bagehot, William noticed Evelyn dressed as a tube of rose madder paint and said to her, “I’m madder still!”* From this moment on, the De Morgans were united in their lives and in their art.

William was much older than Evelyn and was friendly with painters and artists from the generation before hers, such as Henry Holiday and Simeon Solomon, whom he had met at the Royal Academy Schools during his formative years as an artist. William had a very different childhood from Evelyn, having been born to Augustus De Morgan, the celebrated mathematician, and Sophia Frend, the social-reform campaigner and celebrated spiritualist and psychic medium. Sophia and Evelyn formed a special bond, with many of Evelyn’s paintings depicting Sophia’s spiritualist vision. Earthbound (Fig. 3) shows an elderly miser so concerned with material wealth that he fails to see emancipated spirits ascending to the celestial realm, or the angel of death looming with her cloak of oblivion. The message is clear: live a non-materialist, spiritual life on earth to progress to a higher realm upon death.

William also went against his parents’ wishes in order to become an artist. It seems that his father wanted William to follow him into academia and become a mathematician. William instead enrolled at Cary’s Art Academy in Bloomsbury, London, to learn to draw from casts of antique sculptures and ultimately passed the entrance examination of the Royal Academy Schools in 1859. After four years of study and showing limited skill as a painter, he met William Morris and was so enchanted by the designer and socialist thinker that he decided to leave the academy and become a designer himself.

The first ten years of William’s professional career in the decorative arts were dedicated to the design and manufacture of stained glass, which he enjoyed and found profitable. It was during his preparation of stained glass that he noticed something remarkable. If he starved his glass kiln of oxygen, the prepared glass would misfire, causing an iridescent metallic layer to adhere to the surface, rather than form a transparent yellow stain. De Morgan was reminded of ninth-century examples of lusterware from Syria and Egypt he had encountered in the British Museum, and vowed to dedicate his life to re-creating this lost art. He reached his peak with the style in the 1890s when he was able to produce lusterware in three different colors, a technique unmatched by ceramists today. In glistening silver and copper on an ethereal blue base, this pottery is known as De Morgan’s “moonlight suite,” his Moonlight Lustre Galleon punch bowl being a particularly fine example (Fig. 4).

William established De Morgan and Company in 1872 at his family home in Chelsea. He began by buying blank plates and tiles to decorate in luster glaze; Running Antelope Dish is typical of his work from this early period (Fig. 5). William ran the business in Chelsea for a decade before he outgrew the terraced house and moved to be closer to Morris in a factory at Merton Abbey, outside London. Here, his designs became more creative as he finally had the space and expert staff to throw pots to his own design, matching the shape to the surface decoration. Fish and Net vase from this period is a triumph; the net pattern twists and grows as the bulbous vase swells (Fig. 6).

Following a long engagement, William and Evelyn married on March 5, 1887, both bringing their own skills, talents, and professional networks to this most unusual Victorian marriage. The ceremony was held at St. Pancras Registry Office, going against the norm of a church wedding. They moved to their first home together in Chelsea, which had been purchased six months earlier by Evelyn under her maiden name, demonstrating her position as the primary breadwinner. Far from being intimidated by this, William was incredibly supportive of his wife’s career and independence, and would later go on to publicly support the women’s suffrage movement, using his public platform to speak out about inequality. He became vice-president of the Men’s League of Women’s Suffrage in 1914 with the hope of furthering their campaign. Evelyn’s painting The Gilded Cage depicts a wealthy woman trapped in her home in a loveless marriage as revelers pass by outside (Fig. 7). She is likened to a caged canary, beautiful but denied autonomy and freedom. It was a situation familiar to many women in Victorian Britain, and Evelyn’s confidence to paint the scene shows her ambition to speak out in favor of the suffrage movement.

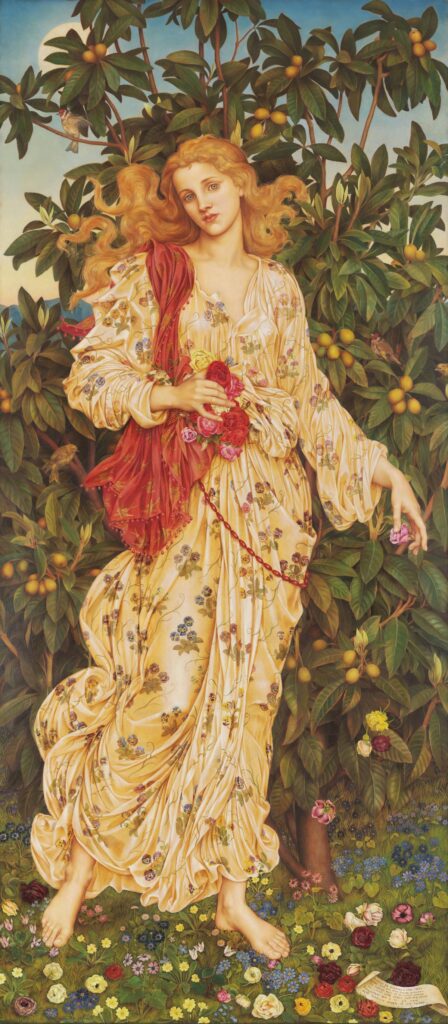

The De Morgans spent six months of each year in Florence starting in 1890, primarily to avoid cold London winters, which were bad for William’s health. Both artists benefitted from being in Italy and viewing Renaissance art. In particular, Evelyn’s Flora is a stunning tribute to Italian art (Fig. 8). The goddess of spring, who Evelyn associated with the city of Florence, is the star of the eponymous painting. In a contrapposto pose suggestive of Sandro Botticelli, Flora is meticulously painted in Evelyn’s signature gold, so the figure literally shines.

The De Morgans both continued to make art until the end of their lives. Although De Morgan and Company closed in 1907 due to financial difficulties, the ever-inventive William turned his hand to writing and was a successful author until he died in 1917. Heartbroken, Evelyn designed a beautiful headstone for them featuring two angels; she died two years later. They left a legacy of artworks that are not only beautiful but also promote the ideals of equality and inclusion of their makers.

A Marriage of Arts and Crafts: Evelyn and William De Morgan is on view at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, California, to January 7, 2024.

SARAH HARDY is the director of the De Morgan Museum in Barnsley, England. A version of this article originally appeared in ArtLetter, the patron magazine of the Crocker Art Museum.

* Quoted in A. M. W. (Anna Maria Wilhelmina) Stirling, William De Morgan and His Wife (New York: H. Holt, 1922), p. 194