If impressionism was born on the boulevards and in the ateliers of Haussmann’s Paris, the two succeeding stages of the modern movement, post-impressionism and fauvism, derived their energy and even their existence from artists fleeing the capital. Although Paul Gauguin, at the vanguard of this renunciation, originally headed north and west to misty Brittany, he soon turned his sights to the South of France, and many others followed him there. A new show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Vertigo of Color: Matisse, Derain, and the Origins of Fauvism, examines the remarkably fruitful summer that the two artists of the title spent in Collioure, just miles from the Spanish border, in 1905.

Precisely because the migration of French painters did so much to put that part of the world on the map, it is hard for us to appreciate just how foreign the fishing villages of St. Tropez, Cap Ferrat, and Collioure once seemed to these artists. Surely the little coastal towns were part of France, the center of the universe, but they were not the France that one knew, the France that mattered, which is to say, the industrialized North.

By the time Henri Matisse and André Derain arrived in Collioure, a number of artists had already preceded them. Paul Signac, who had such a powerful influence on the young Matisse, stayed in the town as early as 1887, while Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh went one year later to Arles (also in the South, but on the other side of the country). When Matisse and Derain visited it, Collioure was a small fishing village, rich in donkeys and white houses, but with few accommodations for strangers. As such, it was quite unprepared for the likes of Matisse and his family, let alone for André Derain, who arrived a few weeks later, dressed like a Parisian fop, trailing trunks, suitcases, and parasols. The thirty-five-year-old Matisse moved into the Hôtel de la Gare beside the train station, and only with difficulty could he prevail upon the harpy who owned the establishment, one Mme Pare, to allow him to bring his wife and three children over from the nearby city of Perpignan.

Amid the humble, unsophisticated life that Matisse and Derain discovered in Collioure, an existence that seemed to be scarcely one step up from savagery, one sensed the enduring resistance of the Albigensian heretics of the Middle Ages to the hegemony of the North. Like Gauguin’s “discovery” of Brittany and then Tahiti, the arrival of Matisse and Derain was a step along that path to primitivism, which, two years later, would result in Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and Matisse’s own Blue Nude (Fig. 7).

Above all, Matisse and Derain had come for the light. And in that light they found color saturated to a degree of intensity that French painting had not seen in centuries. It is tempting to find in the pervasively gray Parisian climate, bred into its inhabitants for generations, an aversion to the harsh purity of the colors that now revealed themselves to the new arrivals in Collioure. A generation earlier in “Art Poétique,” Paul Verlaine had enjoined his fellow members of the symbolist movement to seek “pas la couleur, rien que la nuance,” not color, only the gradations of color.

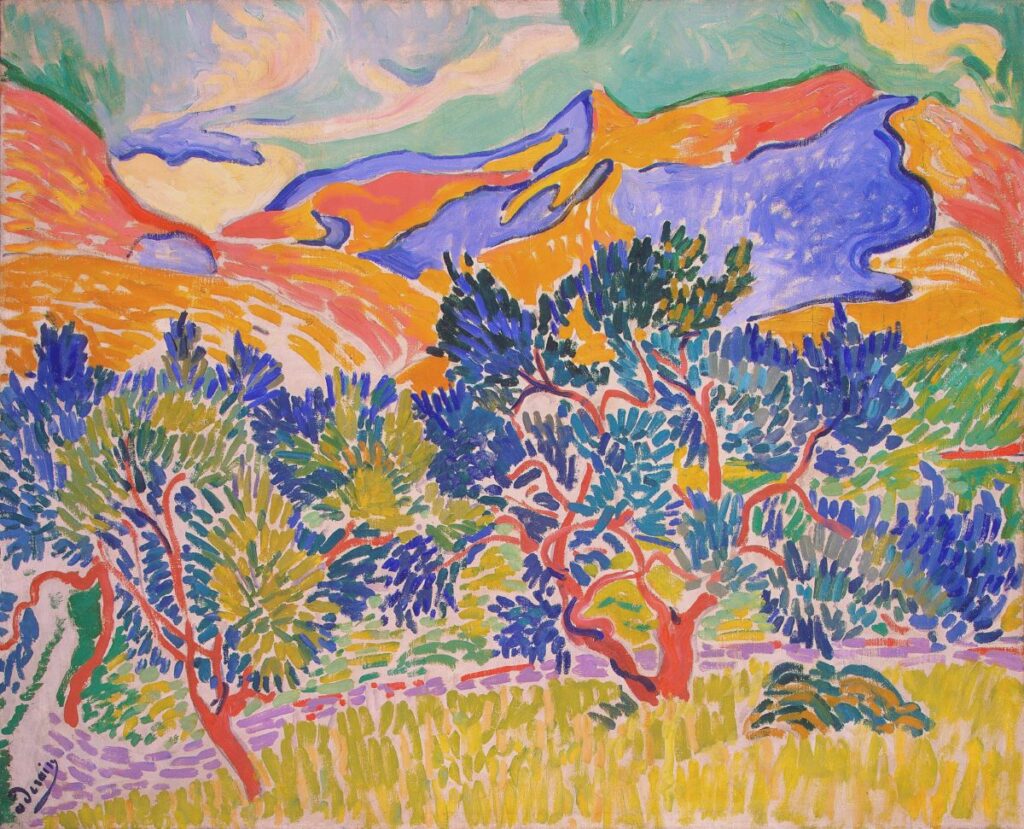

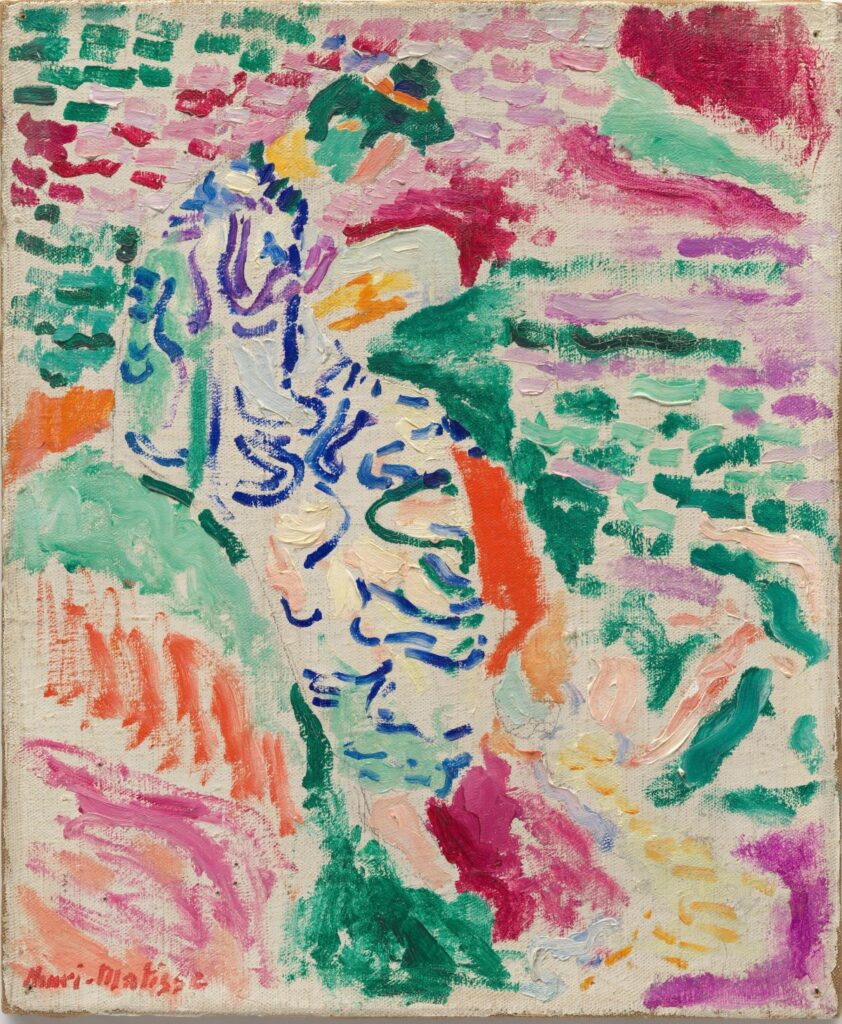

Matisse and Derain were having none of it. And in their refusal, fauvism was born and modernism entered its next stage, one more radical than anything that had gone before. Even the works of van Gogh, that child of drizzly Holland, seem to pull their chromatic punches when set beside the primal force, the ripe immediacy of what Matisse and Derain brought back from Collioure. The reds that surround Madame Matisse in Derain’s portrait of her in a kimono (Fig. 2), no less than the greens that define Matisse’s Landscape: Broom (Paysage: Les Genêts) reveal a use of color that seemed radically new to Western art (Fig. 3). In Mountains at Collioure, Derain could almost claim to have discovered the color orange, so bold is its use in this work, and so hesitant its application in earlier Western art (Fig. 4).

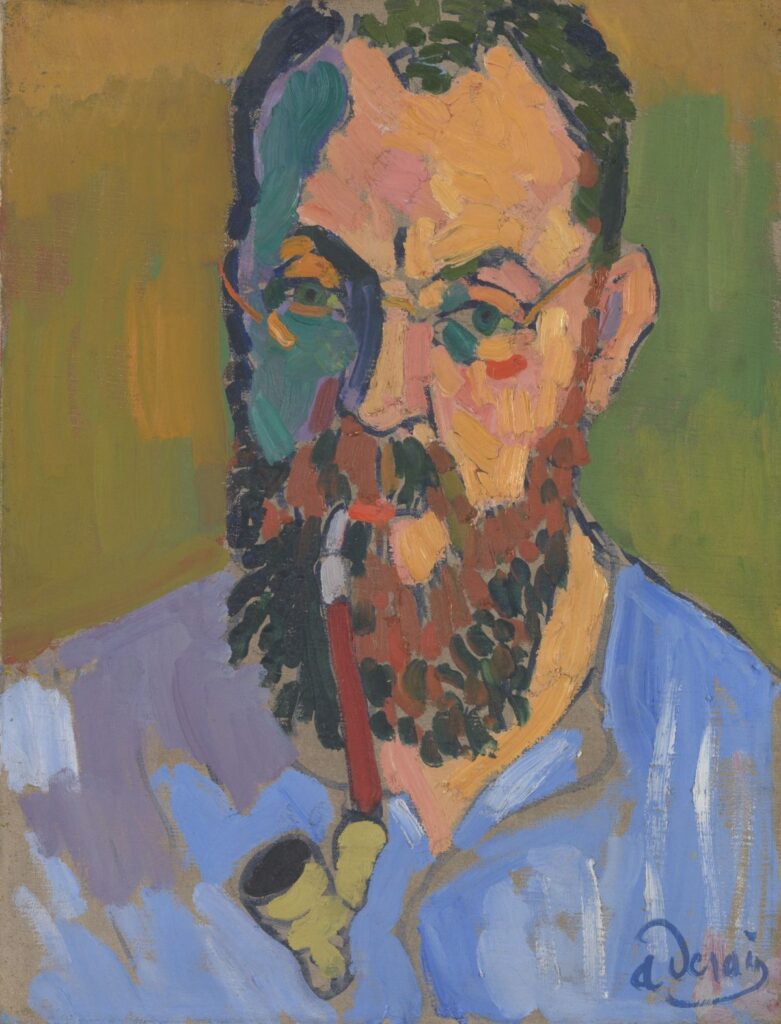

By the time the two artists had completed their nine-week sojourn in the South, Matisse returned to Paris with fifteen completed oil paintings, forty watercolors, and almost one hundred drawings, while Derain brought back thirty works on canvas, twenty watercolors, and fifty drawings. The paint was scarcely dry on them when, only a few weeks later, they were included in the annual Salon d’Automne, which opened in the Grand Palais on October 18, 1905. Derain submitted five paintings and four pastels to the show, among them The Drying of the Sails at Collioure and, possibly, the portrait that he painted of Matisse himself (Fig. 8). Matisse, for his part, submitted two watercolors, three drawings, and five paintings (one completed after his return from Collioure), among them the famous Open Window, Collioure and La Japonaise: Woman Beside the Water (Figs. 1, 5).

This was the occasion upon which the critic Louis Vauxcelles famously described the artists as fauves—“wild beasts”—and thus coined the name given to fauvism (as he would coin the term cubism two years later). In Salle VII of the Grand Palais, it happened that two very classicizing busts by the beaux arts sculptor Albert Marque were set among the works of Matisse and Derain and several like-minded painters. “The candor of these busts,” Vauxcelles wrote in the October 17 edition of Gil Blas, “is surprising in the midst of the orgy of pure color: Donatello among the wild beasts [fauves].”1

The catalogue of the present exhibition, eager to make the case for the art on view, would have us believe, according to an essay by Dita Amory, that “at the close of summer, Derain and Matisse departed Collioure with a body of work that would reinvent painting.” The author is referring not only to the “discovery” of color for its own sake, but also to the final rejection of the divisionism—more commonly known as pointillism—that had defined the work of Georges Seurat and Signac nearly a generation before. This rejection seemed, to the two artists involved, to be a crucial advance. “Fauvism,” Matisse would later declare, “overthrew the tyranny of divisionism.”2 But tyranny is surely too strong a word for a style used mostly in pallidly lovely landscapes. There were many other options open to the painters of the day, in the works of van Gogh, Gauguin, and Paul Cézanne, to name only the most eminent. Furthermore, adherence to the pointillist technique, an adherence that had always been fairly limited, was fading fast by the time Matisse and Derain hit the beaches of Collioure.

Their sojourn in the South of France was to be important for a different reason: it was an essential step in the ultimate liberation of Western painting from its fealty to retinal reality, a severance that would become an accomplished fact only a year later, in Matisse’s Joy of Life from 1906, even though it is already suggested in the figures that populate his Luxe Calme et Volupte of 1904. What seemed so radical and new in the works from Collioure was an insistent intuition of freedom, even emancipation, from the dictates of that mimetic obligation that had weighed on Western painting since the time of Masaccio five centuries before. We can almost feel, indeed, we can almost smell the fresh sea breeze prying wide the casements in Matisse’s famous masterpiece Open Window, Collioure. And through that window we see in the offing, beyond the potted plants and the boats bobbing on pink waters beneath a purple sky—the future of Western art.

Vertigo of Color: Matisse, Derain, and the Origins of Fauvism is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art to January 21, 2024.

1 Quoted in Ann Dumas, “The Salon d’Automne of 1905: A Baptism of Fire,” in Vertigo of Color: Matisse, Derain, and the Origins of Fauvism (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2023), p. 53. 2 Quoted in Vertigo of Color: Matisse, Derain and the Origins of Fauvism, p. 62.