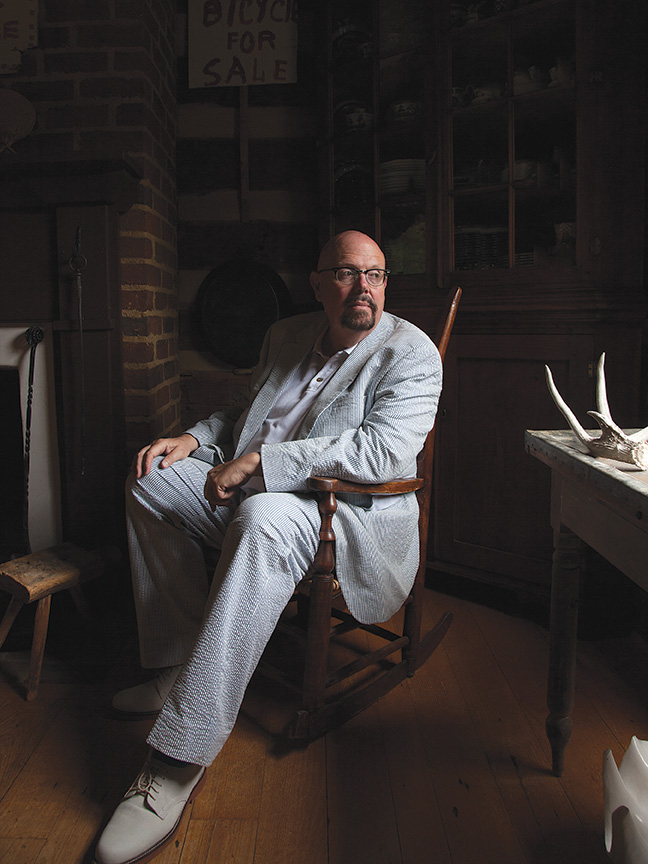

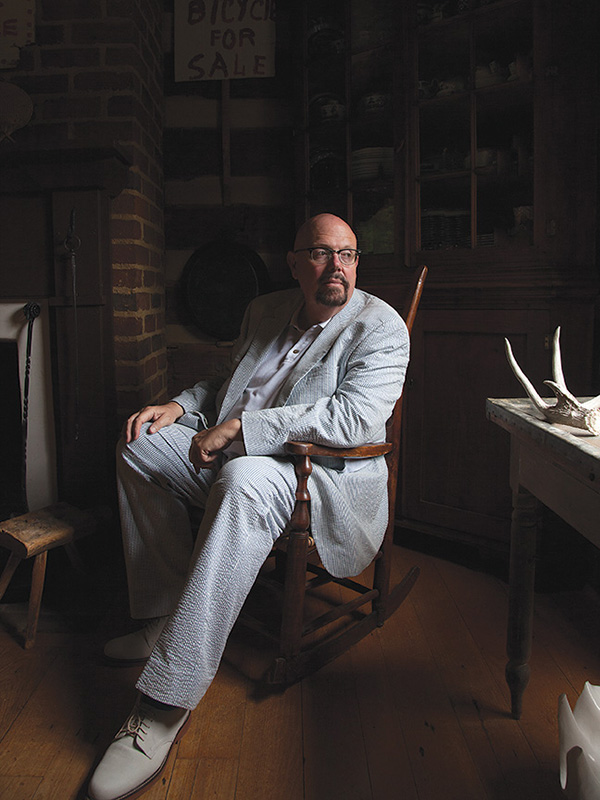

Can there be more than one Robert Hicks operating out of a cabin called “Labor in Vain” somewhere near Nashville, Tennessee? You might be forgiven for thinking so. The Robert Hicks whose essay appears below is also a best-selling novelist (The Widow of the South, A Separate Country, and the forthcoming The Orphan Mother); a former music publisher and artist manager for a range of genres, from country to alt rock; a maker of award-winning, hair-raising small batch bourbon; a preservationist whose focus is on Civil War sites, including the battlefield at Franklin, Tennessee; and a collector of southern material culture with a unique sense of what collecting can mean in the South.

My older brother once summed up my passion for collecting by saying, “Robert was born with more of the ‘hunter-gatherer genes’ than most other kids.” While he may be right, I would like to believe there is something deeper, more worthy in this passion than simple DNA.

Sally Mann introduced her collection of photographs in Deep South by recounting an English traveler’s observation that Europeans have so often identified with the region because of what they call the “lingering aftertaste of defeat.” She went on to explain that “Europe is a continent of defeated nations, but in America only the South has known the tread of the occupier’s boot and the homeward shamble of defeated soldiers.” The traveler’s conclusion was that “pain is a dimension of old civilizations; the South has it, the rest of the United States does not.”

So how’s that to begin an essay on collecting? My point in all this is that if the scarlet thread of defeat does still run through the South, then surely I can make a case that my passion is not just DNA at play, but is born out of some southern need to hoard up what is left. Faulkner wrote an entire novel about the loss that motivates southerners in Absalom, Absalom! beginning with Quentin Compson trying to answer his roommate’s questions about what the South is. Surely, I can use it as the foundation for a piece on collecting.

Truthfully, I can’t remember a time when I didn’t collect. Under my bed, as a child, there were shoe boxes filled with fossilized shells from our driveway, leaves from our lawn, and myriad baseball cards, lead soldiers, coins, stamps, books, and just about anything else that somehow inspired me. With a passion for collecting things came my earliest attempts at connoisseurship, way before the word entered my lexicon. Somehow the concept of “good, better, best” was there from the beginning as I honed my collector’s eye, whether it was for shells, rocks, leaves, stamps, or bottles.

My collecting took a giant leap forward one Saturday at the Nashville Flea Market, sometime in the spring of my senior year in college. It came in the form of a rather large walnut pie safe from Indiana. Without knowing it, I had passed through a doorway into the world of adult collecting. As I filled that longing to collect, I began a parallel quest, to understand. That pie safe, like so many of the other things I have dragged to my cabin over the years, was eventually “upgraded” but it had set me on my way. Simple, primitive American furniture gave way to the quest for specifically southern, plain-style forms, which eventually led to more specifically Tennessee examples. Over the years I have owned seven or more sugar chests and I’m not dead yet.

Like every good collector I have known, much of the strength of my collection rests on who you know and what you learn from them. The list of those who have guided me is long, but at the top would be Dr. Benjamin Caldwell, Rick Warwick, John Bivins Jr., Andrew Glasgow, Jane and John Luna, and Deanne Levison. Each in their own way and in their own fields helped me fill that need to hoard up what is left. Along with passion and knowledge the other key to collecting is a lot of dumb luck. As one who normally defines luck as the result of hard work, it’s hard for me to admit that much of my collection has been the result of happy accidents along the way. Yet I have no doubt that any serious collector can give example after example of how an object found them more than they found it.

Collecting southern furniture eventually led me to the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts (MESDA) in Winston-Salem, where I spent three summers at its Summer Institute and afterwards traveled around with the late John Bivins, one of its “resident scholars” of sorts. There, my passion for southern furniture exploded in several directions—southern textiles, tinwork, iron-work, and ceramics. I use the term ceramics to cover a panoply of forms from early eighteenth-century English salt-glaze and redware to contemporary southern face jugs and utilitarian wares such as chicken waterers and storage crocks.

Some of my time with John Bivins was spent in the Low Country in and around Charleston. Using the aforementioned “good, better, best” of connoisseurship, I discovered the African-American sweet-grass coiled basketry of the late Mary Jane Manigault and began to collect and commission her baskets. She was the best in her field, just as Burlon Craig was of the North Carolina face jug makers or Mark Hewitt still is as a traditional potter.

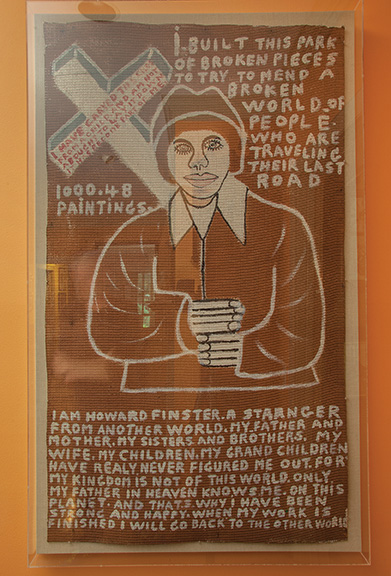

About the time I was discovering MESDA, an article appeared in Esquire about a Baptist minister in Summerville, Georgia, who had been called by God to create sacred art. As I was on my way to Florida for a wedding, I located Summerville on a map and decided to pop by.

Little did I suspect as I pulled into Rev. Howard Finster’s “Paradise Garden” the impact that he and outsider art would have on my life. What was supposed to be an hour-long stop turned into a six-hour layover and a life-changing experience. I had come face-to-face with one of those artists who had littered the landscape of the rural South I had traveled all my life, proclaiming the gospel to a dying world.

While repentance was at the center of his creation of sacred art, there was so much more to Howard and his work. His conviction that he had been called by God to turn the world away from sin and destruction and toward the Light by creating art had me hooked.

Without realizing how far this encounter was to take me, I had already found the perfect complement to nineteenth-century southern material culture. Then and there, I became a collector of outsider art. Just as the South of my ancestors, the South I was born into, seems forever destined to struggle with issues of race, loss, and redemption, so these men and women, working outside the framework of the art world, search for answers within that struggle.

Over the years to come, there were many visits to Howard’s. Long hours were spent in his Paradise Garden as he laid out his vision for saving humanity through art. I was like a hog in pig slop and kept bringing friends down to meet him.

I soon learned from my friend Andrew Glasgow that there were more of these artists out there. The South seemed to be peppered with men and women who felt called to create art—sometimes sacred, sometimes far from it.

Using marked-up maps and scribbled notes, I began to lay out what I called “art cruises” through Alabama, Mississippi, Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, and Georgia. At the heart of this collecting was the time spent one-on-one with the artists: Raymond Coins, Mary T. Smith, Jimmy Lee Sudduth, Georgia Blizzard, Mose Tolliver, Rev. B. F. Perkins, Vannoy “Wireman” Streeter, Homer Green, James Harold Jennings, and a legion of others.

My Ford F-150 pickup (not exactly the perfect art mobile) would come back to my cabin loaded with treasures. And with each return, my cabin looked less and less like anything that might one day make the pages of The Magazine Antiques. Gone was the once fairly traditional furnishing scheme as it gave way to a mixture of the past and present, all overridingly southern.

This is the world I inhabit: a cabin where a ticket to Andrew Jackson’s impeachment, a collection of picture nails, and a classical sofa in its original horsehair can rest in perfect ease with paintings by William Aiken Walker, Gilbert Gaul, Carroll Cloar, and Will Henry Stevens along with jars of green beans my great-grandmother canned over a hundred years ago. Whether it be Dr. Hezekiah Oden’s secretary bookcase used by Nathan Bedford Forrest after the Battle of Franklin or Rev. Howard Finster’s version of the Last Judgment altar in the Sistine Chapel, renamed by Howard Shortest Message: Up or Down, everything comes with a story.

Faulkner continues to remind us that we southerners are nothing without stories. Truth is, the back-story of an object is often as important to us as the object itself. Like the older folks in my childhood, I still want to know “who your people are.” After all, I am a southerner.

Photography by Don Freeman