When I visited artist Abigail Tulis at her studio in Long Island City’s Silks Building a few months ago, every available surface served as either a temporary plinth for her sculptures, or was strewn with her drawings and paintings. Putti flounced across the pages of colorful deckled-edge paper on a big flat file in the middle of the room, keeping company with Sybil-like figures emerging from ornate architectural settings, and erotic paintings that recalled Greek red-figure pottery. Against the wall by the double-height windows squatted a scuffed-up tea table Tulis had scrounged from the street, its legs extended with twisted metal piping that gave it a distinctly insect-like appearance; nearby, a huge watercolor stretched across the floor next to a collection of plaster nudes. The long-legged table and the watercolor, along with a polychrome terra-cotta bust of a soldier (after a sculpture by Verrocchio), would soon be on their way to Booth Gallery in Manhattan, where Tulis was scheduled to participate in an exhibition on contemporary surrealism. She had a lot of work to do to get ready for the show—on top of that, she was getting ready to move studios, too.

“I decided to become an artist when I was thirteen,” Tulis says. Not a contemporary artist, per se. “I thought everything that was being made today was garbage and I just dismissed it.” Home-schooled in Chattanooga, Tennessee, she’d grown up reading classic literature—Dante’s Inferno, The Lord of the Rings, and the Brontë sisters—as well as taking painting and ballet classes, and running around in the woods. At fifteen she apprenticed to local sculptor Cessna Decosimo, a maker of bronze figures for courthouses and parks. One of her earliest artistic efforts under his tutelage was a copy of the Belvedere Torso.

“[Decosimo] was very much part of the more figurative movement that you could say [realist] painter Jacob Collins was also a part of,” Tulis says, and it was at Collins’s school, Grand Central Academy (now Grand Central Atelier), a certificate-granting program also in Queens, that Tulis matriculated when she turned eighteen. At the time, it seemed like a perfect fit. “I kind of thought, ‘Oh, they’re making old style paintings, that’s what I want to do,’” she says. But, as she explains, “I got there and I was like, I’m not really interested in neoclassicism, I’m not interested in David. I’m not interested in Bouguereau.”

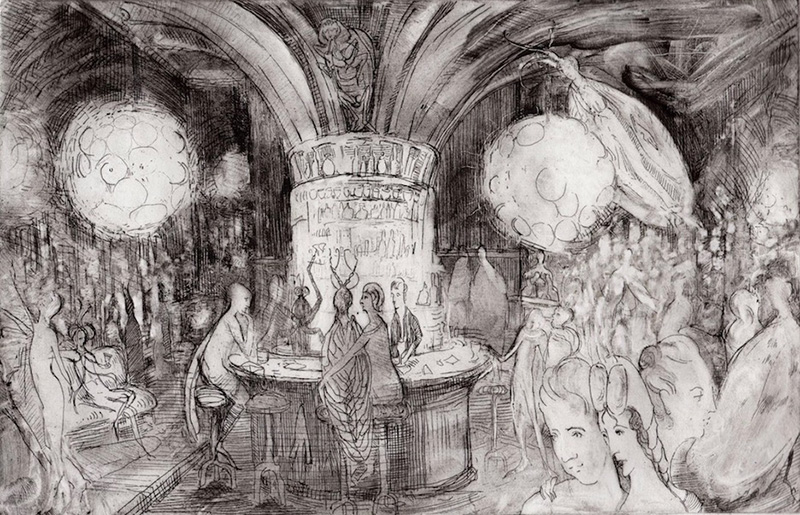

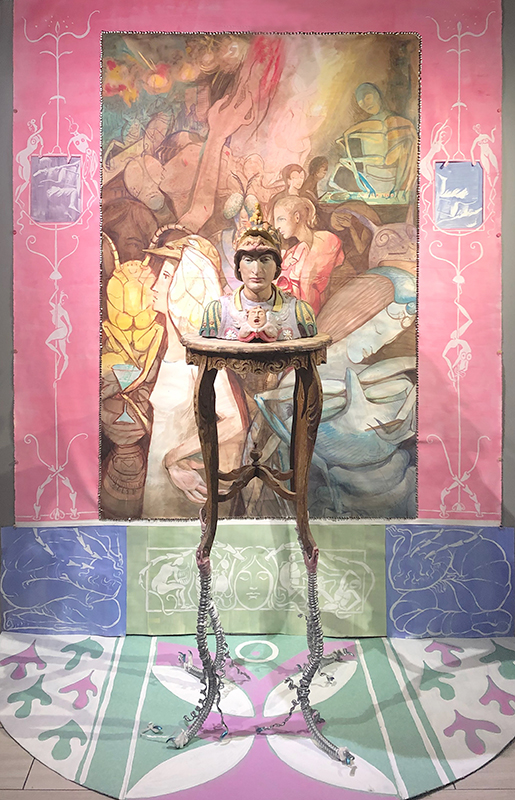

What chafed Tulis in particular was the lack of attention she says composition was receiving. It’s the element of design that Tulis—who likes to describe her works as short stories or poems—uses to introduce narrative into her work. Take, for example, the watercolor that lay on her studio floor when I visited. Entitled Berlin Club, LES, New Year’s [Eve After Heartbreak], it depicts a colorful, well-dressed crowd of patrons at Berlin, a nightclub in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. The scene is framed by an architectural frieze of millennial pink that’s sprinkled with whimsical porcelain-white nudes, as well as photographic self-portraits that evoke bas reliefs. Berlin Club was hung on the wall at Booth Gallery—“like a fake fresco,” Tulis says—and in front of this backdrop sat the bust of a soldier on its metal-legged plinth. “It’s like he’s coming out of the painting,” Tulis explains. “When you pair [Berlin Club and the bust] together . . . there becomes a story that he went to the club, and an unsuccessful conquest has taken place.”

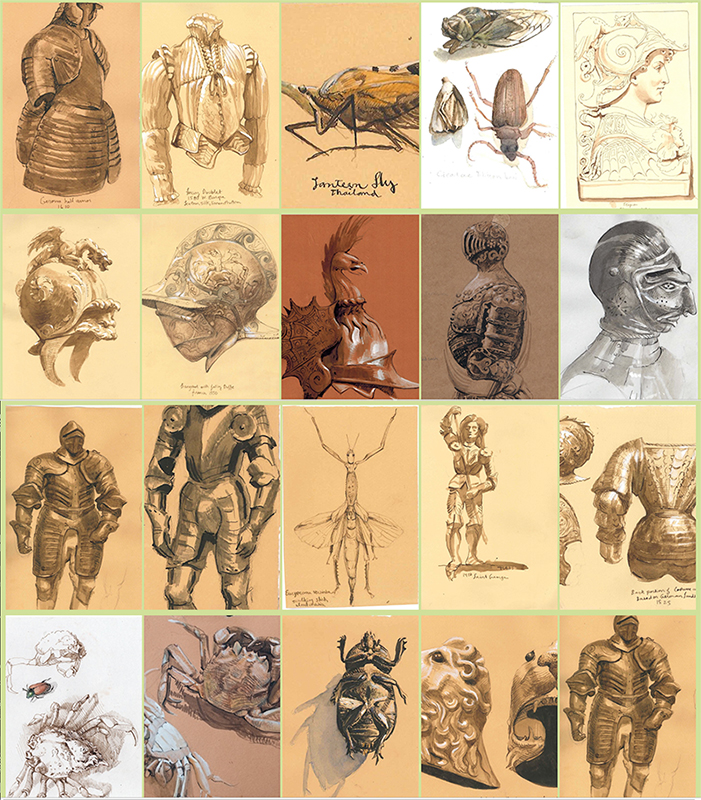

There’s something peculiar about Berlin Club: most of the people look like . . . well, sort of like insects. In fact, entomological elements are apparent everywhere in Tulis’s oeuvre. Tulis explains the irruption of this motif into her practice as the result of a visual connection she made. While a participant in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s copyist program, which allows artists to paint or sculpt objects in the museum’s galleries, Tulis spent a significant amount of time sketching armor in the Gothic halls. After observing some insects in Chattanooga, she “realized [armor and insects] have the same [visual] language.” Although grotesqueries and the macabre are hallmarks of contemporary realism—from the work of Polish cult favorite Zdzisław Beksiński to fantasy drawings posted on the website DeviantArt—it would be incorrect to see Tulis’s use of arthropod imagery as symbolic of deformation or decay. With their eye-catching colors and contours, insects are “like more expressive people,” she says, or “souls that are very sensitive and need protection.”

Still in her twenties, Tulis manages to support herself entirely through her art, doing so in part by way of commissions she’s received from the likes of the C. S. Lewis Institute, interior designer Katie Ridder, and Ridder’s husband, the classical architect Peter Pennoyer. A few years ago, Pennoyer was building a house for himself and his wife in Millbrook, New York, and wanted a frieze on the third-floor exterior that would depict his beloved dachshund, Teddy. “Peter took a huge risk on me because I had never done anything like that before,” Tulis says. “I just had to figure out how to make something that I never made before.”

She borrowed some dachshunds and rabbits from friends and started to sculpt. Her first proposal, a busy composition of animals frolicking amongst carefully-observed foliage, was rejected by the project’s lead designer, Gregory Gilmartin, deemed too complex to be legible three stories up. Heading back to the drawing board, Tulis simplified her design. The final version consists of three simple panels, depicting, respectively: a dachshund running, a rabbit running, and a dachshund at rest. Cast in resin reinforced with fiberglass, the panels are mounted on a rounded bay. Tulis carefully thought through the effects that sunlight would produce on the panels over the course of a day. “I really wanted to use the sun cycle to tell a story of the dachshund jumping towards the hare—which is what’s illuminated in the morning—and then you see a satisfied dachshund resting when the sun sets.”

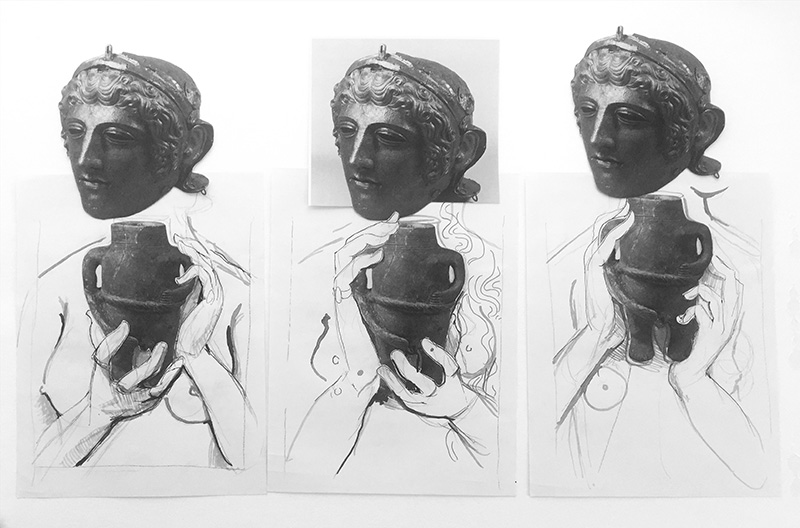

For her efforts, Tulis would win the 2017 Stanford White Award from the Institute of Classical Architecture and Art. But at the time she finished the commission she was unsatisfied. “I felt like I couldn’t speak the [sculptural] language that I was trying to use,” Tulis says. Her thoughts turned toward Europe and in 2015 she made her first sojourn to Italy, where she sketched everything that caught her eye. Receiving a second commission from Pennoyer, Tulis had the idea for a pair of tondos—circular relief carvings of the kind that became popular in Italy during the Renaissance—one depicting the Judgment of Paris, the other showing Dionysus flanked by a pair of maenads.

“I’m trying to make something in this larger [historical] dialogue, not just artistically, but spiritually and mystically,” Tulis says. Over the next year she wants to concentrate on decelerating her current Dionysian creative stage, and to help her focus she’s relocated from Long Island City to the bucolic town of Vianen in the Netherlands. The Covid-19 pandemic has ended up an unexpected ally in her quest for calm, she says: “Honestly, it’s just helping me get to my goal of an art nun life faster than I would on my own.”