At the New York School of Interior Design on May 6 the Manitoga Design Industry Council convened a panel, “Russel Wright—The Growing Relevance of Organic Modernism,” that included landscape architect Carol Franklin; noted textile designer, author, and collector Jack Lenor Larsen; and mid-century furniture designer Jens Risom to discuss the relevance of Russel Wright on today’s design environment.

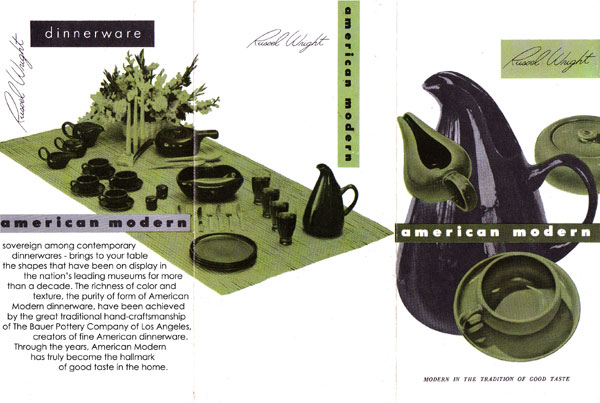

This panel, which was moderated by Donald Albrecht, curator at the Museum of the City of New York, and Katy Moss Warner, president emeritus of the American Horticulture Society, served effectively as a celebration of Dragon Rock (Wright’s home built into the site of a former quarry) and Manitoga (the larger site of 75 acres Wright acquired in 1942) located near Garrison, New York. Albrecht, who curated an exhibition on Wright at the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, in 2001, provided an overview of Russel and Mary Wright’s non-elitist aesthetic of “casual elegance”—epitomized by Wright’s iconic American Modern dinnerware. He discussed Wright’s career as a series of concentric and evolving circles, beginning with Wright’s early experience with set design and ending with Wright as an environmental designer as seen through his intricate series of pathways and constructed views at Manitoga.

Oceana wood line, 1935.

Larsen recollected first meeting Wright in the 1950s at Wright’s Manhattan townhouse, and their subsequent trips to Southeast Asia. For him, Wright’s work hasn’t become dated, but he is most enthusiastic about designs executed prior to World War II for their simplicity and interest “in the common man,” a trend Larsen believes was not characteristic of most post-war practitioners, including himself.

Both Larsen and Risom (who went on to hire Wright’s lawyer) pointed to Wright’s insistence on royalties negotiated for the life of the executed design—an important yet overlooked aspect of Wright’s pioneering career. According to Risom, Wright designed “for normal people,” at a time (the 1940s and 1950s) when contemporary design was a hard sell with the interior design community, because of its threat to their traditional modes of working and making a profit. He stressed that Wright’s comprehensive approach to design truly carried through on his promise of “design for easier living”—a mantra that still resonates today.

Turning to landscape, which occupied much of Wright’s later years, Franklin recalled seeing Wright speak at RISD (slowly, poetically, and a bit boringly), discussing his celebration of the American native garden of the Hudson Highlands. She mentioned the 19th-century horticulturist and landscape architect Andrew Jackson Downing (who authored widely influential design books of cottages and country houses) as a forebear, and, like Albrecht, also viewed Manitoga as an evolution from Wright’s beginnings in set design, with landscape revealing itself through contrasts and progressions. She likened his approach to the Japanese tour garden, with the notion of a “journey of discovery” that was especially effective with children (Wright’s own daughter Ann, grew up at Manitoga). Franklin credited Wright with bringing a human scale to landscape design and saw this same sensibility reflected in the sensuality of his product designs.

Perhaps of greatest relevance for us today was Wright’s search “for the way we live now,” an acknowledgment that successful design is shaped by modern lifestyles and not the other way around.