Decades before the wildly popular German writer Karl May (1842–1912) entranced European readers with his fanciful tales of Native Americans (despite never having set foot in the American West), a scholarly German prince, Maximilian of Wied (1782–1867), came here to do the serious work of documenting tribal life along the Missouri River. Accompanied by Karl Bodmer, a young Swiss artist in his employ, the prince arrived in 1832 with a sense of urgency, keenly aware of the mutability of Native cultures in the face of Manifest Destiny: “the beginning of settlement,” he wrote, “is always the destruction of everything else.”1

He’d not been here long before he also sniffed the zeitgeist of the Jacksonian era with bracing accuracy: “It is incredible how much the original American race is hated by its foreign usurpers.”2

The prince was a naturalist, an ethnographer, and an intrepid adventurer in the mold of his friend and mentor Alexander von Humboldt, and yet, as he later said, if he’d had any idea of the hardships of this journey he might not have undertaken it. We should be immensely grateful that he did. After a grueling but fruitful two years, much of it spent following the trade route of the American Fur Company up the Missouri River from Saint Louis to what is now Montana (and back down again), he and Bodmer returned to Europe and embarked on various ventures to issue the prince’s journals with Bodmer’s illustrations of flora, fauna, and Native life. None of these editions was especially successful, nor were they quite what Maximilian envisioned. Cheaper versions eventually circulated widely and that is where Karl May, the J. K Rowling of his day, found much of the inspiration for his characters Winnetou and Old Shatterhand, captivating readers from Adolf Hitler to Milan Kundera and creating the European phenomenon roughly translated as Indianthusiasm.

Ironically, we have had far more than our share of would-be Karl Mays in this country in print and on screen and yet none has had anything like May’s enduring popularity; after all, their creators did not have Maximilian of Wied to lean on. Despite faults and flaws May’s tales endure with some two hundred million copies in print but it is the prince’s work . . . and Bodmer’s, too, that should captivate us now.

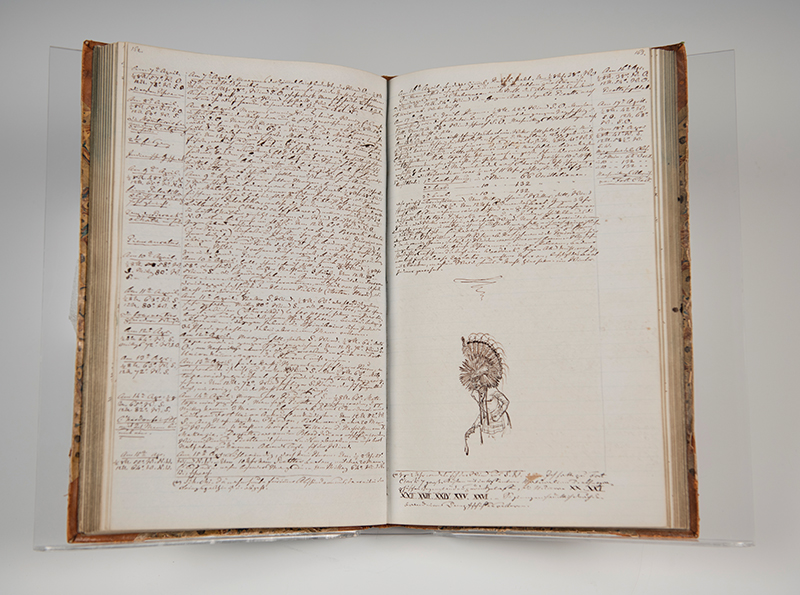

After his death, Maximilian’s journals and Bodmer’s original watercolors languished in Wied until the 1950s, when they were brought to this country, exhibited, and eventually donated to Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha by the InterNorth Art Foundation (later the Enron Art Foundation). Editions of the journals and the watercolors are available here for anyone willing to pay a steep price for them, as I did during a long winter spent hoping for a break in the pandemic that would allow me to visit Omaha to see the originals. I have grown quite fond of the prince over these months of reading his journals and gazing obsessively at the riveting watercolors. Yes, he has his fair share of Eurocentric moments, but mostly he is careful, respectful, meticulous with his efforts at ethnography, and appreciative of Indigenous cultures. Why is the one-volume edition of his Travels not better known? It would be a healthy antidote to Francis Parkman’s The Oregon Trail, surely one of the most repellent books in the American canon.

My desire to get to Omaha is far less urgent now that many of the original Bodmer watercolors have come to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in a pathbreaking exhibition, Karl Bodmer: North American Portraits. This exhibition of thirty-five portraits, six landscapes and genre scenes, and a few aquatints is a work of many years and many hands and I recommend its superb catalogue, Faces of the Interior: The North American Portraits of Karl Bodmer, as one’s guide through some complex, enticing, but dangerous terrain.

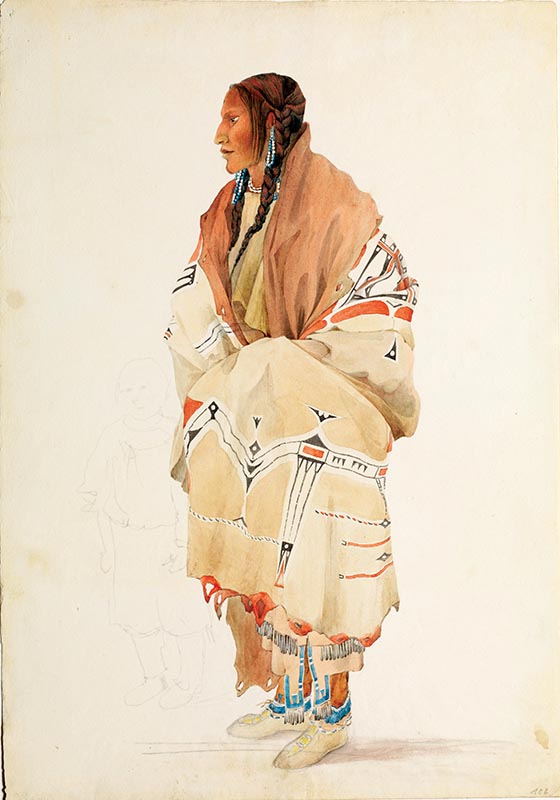

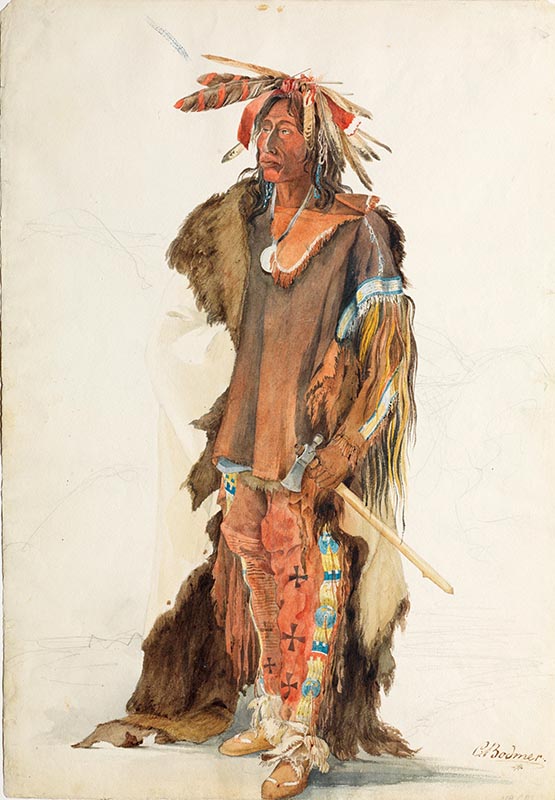

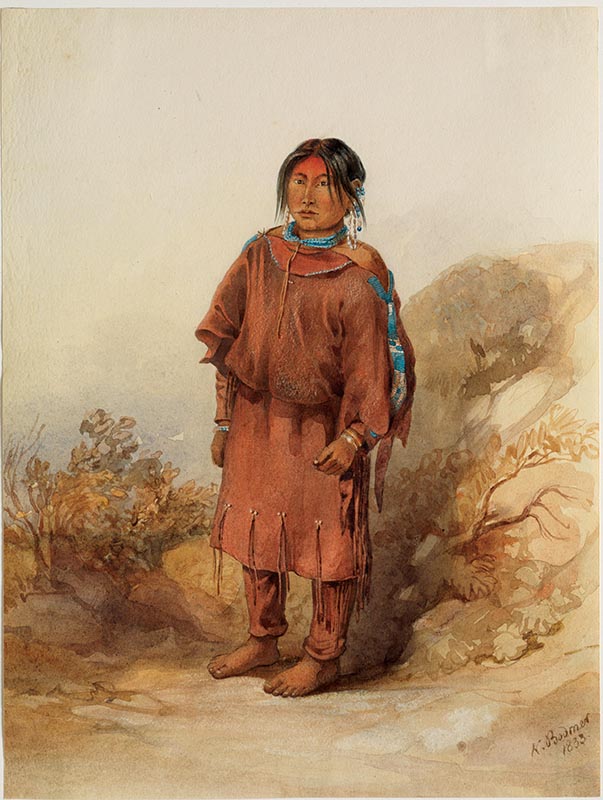

In the young Bodmer, whose work had theretofore been limited to picturesque landscapes rather than portraiture or natural history, Maximilian had a superb draftsman he could shape to his purpose, and that purpose was a scientific fidelity to detail. And there is where the catalogue comes in, cautioning us from a too-credulous reading of these portraits as documentary fact without detracting from what Annika Johnson, Joslyn’s associate curator of Native American Art, describes as their “unprecedented level of detail and nuance.” In addition to information on how the American Fur Company mediated the experience of Maximilian and Bodmer in Indian Territory, you will also find a superb analysis of the way Maximilian’s enlightenment values shaped Bodmer’s work; a sparkling interview with Gerard Baker, who grew up on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in North Dakota and has illuminating observations on both Bodmer and Maximilian; and a precise analysis of Bodmer’s occasional rearrangements of reality, especially as he reworked his compositions for printmaking.

What you won’t find are the wall labels that Annika Johnson and the Met’s curators Thayer Tolles and Patricia Marroquin Norby commissioned from Indigenous people. Because Johnson sees a good part of her mission at Joslyn as engaging Native communities, and because she has done extensive work on George Catlin, who painted at the same time as Bodmer with very different results, I asked her about both.

Can you describe the efforts you and the other curators have made to bring Native perspectives to bear on Bodmer’s depictions of tribal life? Do the wall labels you commissioned help us to look at non-Native art through a Native lens . . . or is that not the point?

Annika Johnson: Thayer Tolles and I decided to invite Indigenous scholars, artists, and tribal elders to contribute to the exhibition by way of writing wall labels. When Patricia Marroquin Norby joined the Met as inaugural Associate Curator of Native American Art in Fall 2020, we were excited to welcome her as a collaborator in this effort to expand the interpretation of the watercolors. An important part of our curatorial process was having extensive discussions with the Indigenous contributors about Bodmer. I can speak to my own experience during this process and say that it transformed my thinking about the significance and challenges of this body of work, and about the potential for future avenues of interpretation.

During these discussions (and in their labels), the contributors not only shared their knowledge about the cultural significance of the sitters’ regalia and the importance of the sitters contributions to their communities, they also raised questions about what is missing from the portraits and journals, especially the absence of women’s stories in these works and how the portraits connect to the present and reveal (or conceal) truths about the past. Cultural continuity and change were also frequent topics of our discussions that come to the fore in the wall labels. The labels are powerful and will undoubtedly impact how viewers look at art of the “American West.” Maximilian provides a wealth of valuable information in his journals, as does Bodmer in his unparalleled rendering of a person’s regalia. Yet we must take these Eurocentric textual and visual interpretations with a grain of salt. We can no longer talk about Bodmer and Maximilian without discussing the colonization of Indigenous homelands and its ongoing legacy. This is not to disparage Bodmer and Maximilian and their work, which is widely regarded by Native and non-Native individuals as invaluable records of one moment in time. Rather, it is to say that we can’t talk about Bodmer’s portrait of an unnamed woman without discussing women’s powerful roles within their communities past and present and the Eurocentric biases that disregarded this; we can’t talk about Bodmer’s riverscapes without discussing the havoc wreaked by Western agriculture and infrastructure projects on the landscape.

The wall labels are a step toward activating these artworks. For instance, how might the Bodmer- Maximilian collection help efforts to revitalize Indigenous languages or to study traditional ecological knowledge? Can Bodmer’s portraits support the work of contemporary Indigenous artists who are studying nineteenth-century styles of regalia making? What stories do these portraits tell?

You have done extensive work on the American painter George Catlin, who painted many of the same tribes at roughly the same time as Bodmer and is better known here. How would you characterize the differences between the two painters and especially their interaction with the Native sitters?

Put in the broadest terms, Catlin was about quantity and Bodmer about quality. Catlin’s portraits were often executed quickly whereas Bodmer spent more time with his sitters, often completing portraits over the course of several days.

Bodmer’s ability to build a relationship with [Mandan leaders] Sih-Chidä and Mató-Tópe, for instance, was largely due to the amount of time the travelers stayed at Fort Clark alongside Mandan and Hidatsa villages, which totaled five months. They also stayed there in the wintertime, the season of storytelling when people mostly stayed put. Mató- Tópe was a major figure, known by Native and non-Native peoples, something Bodmer would have been especially attuned to. He even painted Mató- Tópe’s portrait twice. In exchange, the chief gave him a robe painted with his battle exploits, which speaks not only to the Mandan value of generosity but also to the relationship that the travelers were able to establish with their host communities. Sih-Chidä was clearly interested in Bodmer’s artistic practice as he visited Bodmer’s makeshift studio at Fort Clark constantly, even staying there at times. The two exchanged many drawings, and Sih-Chidä’s drawings are now in Joslyn’s collection.

Although Bodmer’s portraits have a stillness to them, they are not static, and this exhibition with its contemporary wall labels and catalogue essays brings them forward to engage the present and inspire future scholarship, exhibitions, and conversations. When Karl Bodmer: North American Portraits returns to Omaha and goes from there to the Amon Carter Museum, it will include a series of short films featuring descendants of the tribal communities Maximilian and Bodmer visited, who comment on the importance and the difficulties of Bodmer’s watercolors. By doing so it will help to dispel some of the nostalgia that often plagues our uses and abuses of Native cultures.

Just three years after Maximilian and Bodmer left the Missouri, a smallpox epidemic brought upstream by the American Fur Company added to the devastation wrought by whiskey, gunpowder, and deforestation, wiping out about a quarter of the tribal populations. Much would have been lost had the prince and Bodmer not stopped to record, consider, and appreciate all that they encountered.

Karl Bodmer: North American Portraits is on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York until July 25. The exhibition will travel to Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska, October 2, 2021, to January 2, 2022, and later to the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas.

1Karl Bodmer with annotations by David C. Hunt, Karl Bodmer’s America (Omaha, NE: Joslyn Art Museum, 1993), p. 86. 2Maximilian, Prince of Wied, Travels in the Interior of North America, 1832–1834 [1843], vol. 22 of Early Western Travels, 1748–1846, ed. Reuben Gold Thwaites (Cleveland, OH: Arthur H. Clark, 1906), p. 70.