In the 1890s a charismatic brunette in her twenties appeared on the Manhattan cultural scene. A South Carolina native, she had just adopted a new name, Hettie Anderson, and she found work posing for artists. By 1906 she was known as “the Goddess-like Miss Anderson,” as the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens wrote. He considered her “the handsomest model I have ever seen of either sex,” and he relied on her stamina for “posing patiently, steadily and thoroughly in the spirit one wished.”1

Artworks inspired by Hettie Anderson are widely scattered: in murals, etchings, gold coins, statues, and at least one skyscraper finial. Yet while featured in high-profile commissions, she avoided the limelight. One photo of her is known to exist, along with a few dozen pages of her correspondence (Fig. 2). Newspaper reporters briefly mentioned her, noting for instance that she was “of the heroic type,” and no one seems to have actually interviewed her.2 The scandalous lives of her colleagues like Evelyn Nesbit and Audrey Munson, meanwhile, made headlines and attracted biographers.3 What is clear from the evidence trail is that Anderson inspired figures exuding calm, dignity, and beauty. “She was a quiet, purposeful person who was very professional and respected as a powerful entity—which resulted in beautiful artworks,” says Willow Hagans, an independent researcher and an Anderson cousin. Willow and her husband, William E. Hagans, who died in 2015, started publishing scholarly articles about Anderson in the 1990s (while also coauthoring a comprehensive book about the Swedish painter Anders Zorn’s trips to America).4 They had first learned about Anderson around 1980 from William’s South Carolina–born maternal grandmother, Jeanne Wallace McCampbell Lee, whose grandmother Martha Lee Wallace was Anderson’s maternal aunt.

The family is African American—southern bureaucrats labeled them “colored” or “mulatto.” Anderson, known to her family as Cousin Tootie, was considered an embarrassment by relatives who battled racism while pursuing careers in medicine and other professional fields. She was rarely discussed “because she takes off her clothes in public,” Lee told the family.

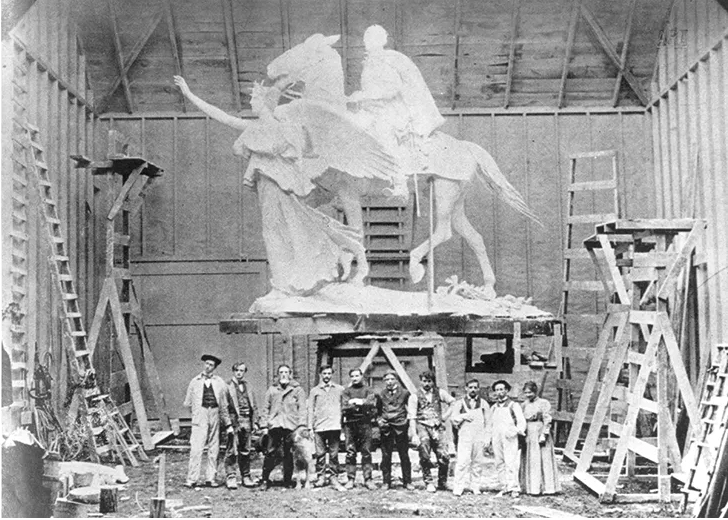

I first learned of Anderson last fall at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition, Making the Met, 1870–2020. On view was a gilt-bronze sculpture, acquired in 1917: a reduced scale version of Saint-Gaudens’s larger-than-life allegorical depiction of winged Victory, part of the General William T. Sherman monument at Grand Army Plaza in midtown Manhattan (Fig. 1). With one arm outstretched and the other grasping a palm frond, Victory leads the weary conqueror on horseback. “She has a certain fierce wildness of aspect, but her rapt gaze and half-open mouth indicate the seer of visions: peace is ahead and an end of war,” the artist and educator Kenyon Cox wrote in 1905.5

Making the Met’s label noted that Anderson was Black, had posed for a number of artists in New York, and later worked at the Met. That poignant last phrase made my eyes sting: she could have been standing right where I was standing, looking at a version of her younger self covered in gold. I wondered what that was like. Henry Duffy, the curator at the Saint-Gaudens National Historical Park in Cornish, New Hampshire, soon connected me to Willow Hagans. She and I have been collaborating ever since and puzzling over the mysteries of Cousin Tootie.

Anderson was born Harriette Eugenia Dickerson in 1873 in Columbia, South Carolina.6 Before the Civil War, the family was designated “free colored persons”; they owned land and earned wages. (Her grandfather Henry Lee, a carpenter, and her grandmother Eliza Lee were likely the offspring of white slaveowners and formerly enslaved Black women.) Her mother Caroline Lee Scott (1839–1928), a seamstress, acquired a cluster of houses in Columbia while still in her twenties. Nothing is yet known about Benjamin Dickerson, listed in documents as the father of Hettie and her older brother, Charles. Caroline’s sister Martha married Andrew Madison Wallace, a bricklayer and musician who had been born enslaved (along with two brothers and their mother) by his father, an Irish-born Catholic priest. In the 1850s Martha and Andrew had escaped to Canada by steamship with their children; they returned to Columbia around the time Anderson was born.

As the region recovered from wartime damage, relatives helped found an Episcopal church and prospered as physicians, dentists, pharmacists, professors, pastors, and civil servants. Among the new higher educational opportunities available were two schools, Benedict College and Allen University (both extant, historically Black institutions today). Although records of Anderson’s formal education have not been found, her letters show sophistication and confidence. But by 1900 or so, with local economies in decline and Jim Crow brutalities worse than ever, virtually all of Anderson’s relatives moved to cities in the Midwest and Northeast.

In Manhattan, Anderson—no one knows why she adopted that last name—and her mother rented an apartment in a sepia-colored brick building on Amsterdam Avenue at Ninety-Fourth Street. She worked as a seamstress and occasionally as a store clerk, while modeling and likely studying at the then-new Art Students’ League on West Fifty-Seventh Street. She also spent weeks at a time at sculptors’ country studios, including Daniel Chester French’s estate Chesterwood in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. “Because she was so much in demand, she could pick and choose which artists she wanted to pose for,” Hagans says. “She maintained control.”

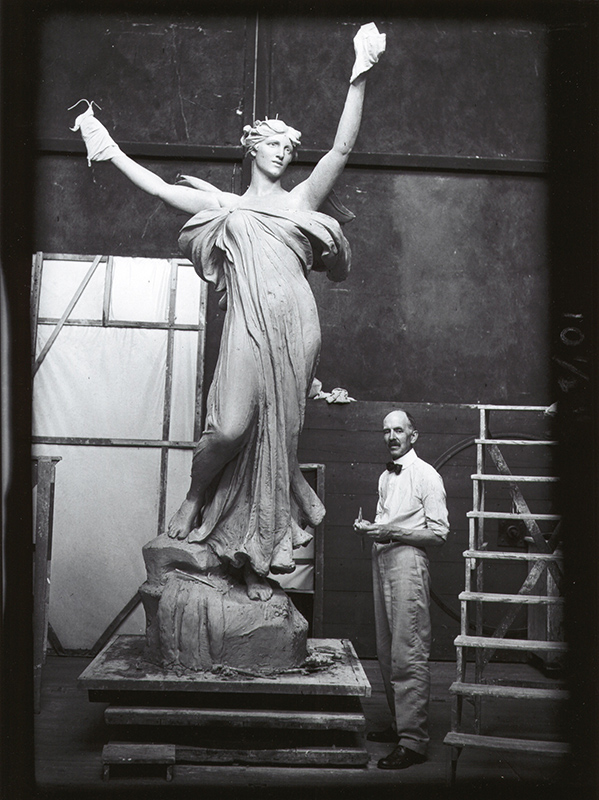

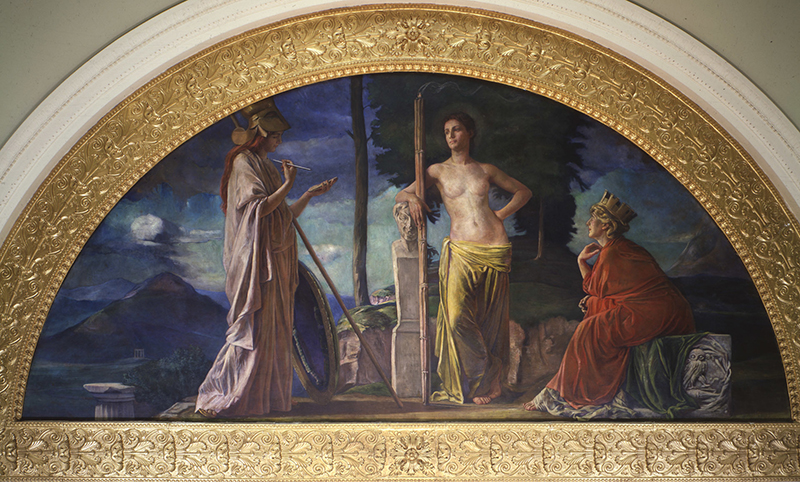

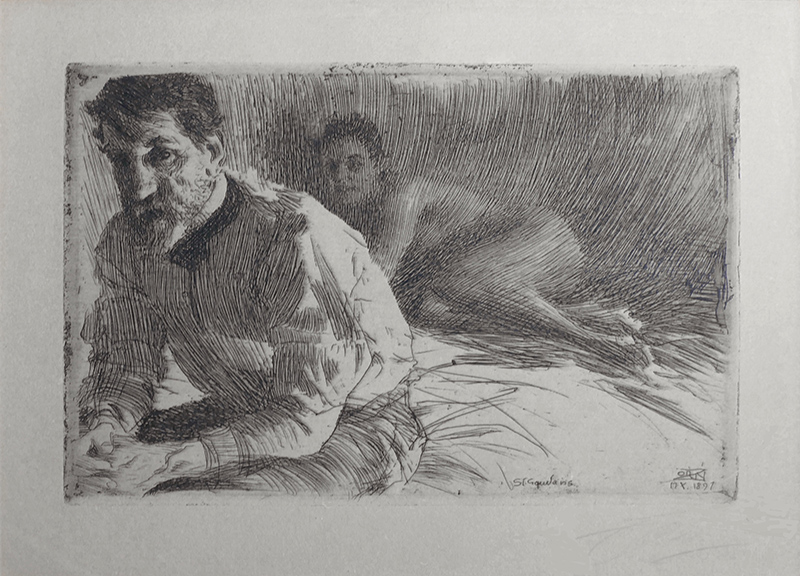

In the late 1890s, artist John La Farge rendered her as a willowy Athenian deity for a lunette mural at Bowdoin College’s domed Walker Art Building (Figs. 7, 8). In an etched 1897 portrait by Zorn, she appears radiant behind a haggard Saint-Gaudens (he would soon be diagnosed with terminal cancer) while taking a break from modeling for Victory (Fig. 9). A few years later, she posed as Liberty for Saint-Gaudens’s coinage designs commissioned by President Theodore Roosevelt—who praised the results as “daring and original,” rivaling ancient Greek precedents and “worthy of this country” (Fig. 10).7 While Saint-Gaudens was perfecting prototypes for a twenty-dollar gold coin, he wrote about Anderson to the sculptor Adolph Alexander Weinman, saying: “I need her badly.”8

Saint-Gaudens gave Anderson her portrait bust in plaster, his first draft of Victory’s head—he genericized the monument’s final version, removing any “overmuch ‘personality,’” as his son Homer later noted (Fig. 4).9 First Sketch of Head of Victory Sherman Monument was cast in bronze at some point. In early 1908, just months after the sculptor’s death, Anderson copyrighted the artwork.10

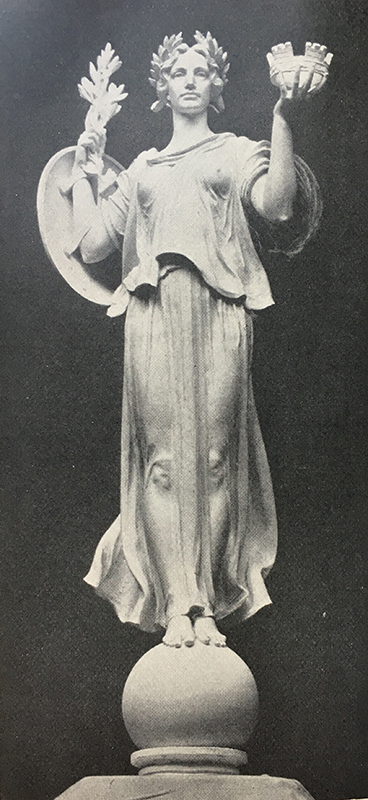

By that time her clients included Weinman; she is said to have posed for his Civic Fame, a gilded goddess crowning what is now called the David N. Dinkins Manhattan Municipal Building (Figs. 12, 13).11 French hired her for Truth, a bas relief of a seer bearing a looking glass and a crystal ball on a bronze vestibule door of the Boston Public Library; The Spirit of Life, a bronze goddess holding a bowl and pine bough in Congress Park in Saratoga Springs, New York (Fig. 6); and Mourning Victory, the centerpiece of a Civil War memorial at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord, Massachusetts. Anderson also posed for French’s Angel of Peace on the grave of the blueblood developer Rutherfurd Stuyvesant in northern New Jersey,12 and Sculpture, an allegorical figure on the grounds of the Saint Louis Art Museum portraying a seated woman holding a carving tool and cradling two unfinished human figures (Fig. 11). French lauded her “perfect faithfulness and thoroughness and conscientiousness” in the workplace.13 She was also hired often by his protégée Evelyn Beatrice Longman, who created numerous public monuments and cemetery memorials.14

Anderson, while maneuvering in the art world, apparently had little fear of the field’s power-brokers. Saint-Gaudens’s widow, Augusta, and son, Homer, had hoped to make replicas for sale of First Sketch of Head of Victory Sherman Monument, but Anderson refused. She insisted that the copyrighted piece would remain most valuable as “the only one in existence.”15 Museums borrowed it for a posthumous Saint-Gaudens retrospective that opened at the Met in 1908 and traveled widely. At the close of its showing in Indianapolis (at what is now the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields), workers accidentally shipped her bust to the sculptor’s family. Anderson wrote blisteringly to the museum’s director, William Henry Fox: “you have committed a grave error in allowing that Bust of mine to pass from your care” and sending it “just where I did not wish it to go.”16 Willow Hagans says Anderson “must have had nerves of steel and determination to defend that bust.” Homer Saint-Gaudens proceeded to scrub Anderson’s identity and the bust’s existence from publications about his father’s work, aside from a reference to an unnamed model “supposed to have negro blood in her veins.”17

It is not known what she told the Saint-Gaudens family or anyone else about her background. New York census takers listed her as “white.” But she definitely did not “pass” or “cross the line”—that is, she did not hide her ethnicity by cutting off family members. Her visitors over the years included her brother Charles Dickerson’s children—he became a horse trainer in southern New Jersey (and concealed his African American heritage)—and her cousin Jeanne Lee.

In the late 1910s, as modeling opportunities faded, French and Longman helped Anderson find work as a classroom attendant at the Met. Her duties included tidying up lantern slides used to illustrate lectures. The museum by then owned a Victory cast and a marble version of French’s Mourning Victory. (Casts of Saint-Gaudens’s Victory can also be found at institutions including the Carnegie Museum of Art, Toledo Museum of Art, and Arlington National Cemetery and on the market.)18 Henry Duffy wonders what her Met workdays were like: “Did she ever let on that she’d been a model? Did she ever tell anybody, ‘I posed for this artist’?”

By the 1920s, Anderson retired, in declining health— though she refused the Met’s offers of sick pay and suggested medical treatments.19 According to Charles’s granddaughters, she suffered a breakdown after seeing a lover killed in traffic on Amsterdam Avenue. Every evening, she would inexplicably open and shut a window, shouting the name of a cousin, Sarah “Sallie” Wallace Arnett, a church leader who likely disapproved of modeling careers. Anderson nonetheless maintained a comfortable nest egg in savings plus diamond jewelry, a grand piano, and a watercolor landscape of Samoa by John La Farge (now unlocated).20 Her 1938 death certificate listed “model” as her profession. She and her mother are buried in unmarked graves in a mostly white cemetery in Columbia, near Woodrow Wilson’s family members and Confederate memorials. In 1990 the Haganses bought the Saint-Gaudens bust at Christie’s in New York.21

Anderson’s peers among Belle Époque artists’ models, white and Black, have attracted recent scholarly attention. In 2013 the Morgan Library and Museum in New York gathered paintings of Miss La La, a Black circus aerialist who posed for Degas. The exhibition Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today (see James Gardner’s review in the January/February 2019 issue of ANTIQUES) was shown in 2018 and 2019 at Columbia University’s Wallach Art Gallery and the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. Last year, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston devoted galleries to Thomas McKeller, a Black bellhop from North Carolina who modeled for depictions of deities and soldiers in John Singer Sargent’s murals. Also last year, a book appeared about James McNeill Whistler’s Irish-born model and mistress Joanna Hiffernan (1839–1886),22 who helped run his business and raised one of his illegitimate children.

Beginning in mid-September, Anderson’s Athenian incarnation will loom a couple floors above the exhibition There Is a Woman in Every Color: Black Women in Art, at the Bowdoin College Museum of Art. And in 2023, artworks that Anderson inspired will be featured in the American Federation of Arts’ traveling show Monuments and Myths: The America of Sculptors Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Daniel Chester French.

I visit Victory in midtown Manhattan often. I eavesdrop as people take selfies below her sandaled feet. Almost no one reads the nearby plaque, explaining the symbolism of Union triumph and identifying Anderson. How fierce she looks, with anti-pigeon spikes atop her head, wings, and fingertips. How few other models of her time maintained their privacy and independence, and how fewer still had the sand to protect their own image by copyright.

1 Quoted in William E. Hagans, “Saint-Gaudens, Zorn, and the Goddess-like Miss Anderson,” American Art, vol. 16 no. 2 (Summer 2002), pp. 81, 85. My work has only been possible thanks to tireless input from independent researcher Willow Hagans. I am also deeply indebted to James Moske and Thayer Tolles, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Dana Pilson, Chesterwood, Stockbridge, Massachusetts; Henry Duffy, Saint-Gaudens National Historical Park, Cornish, New Hampshire; Erica E. Hirshler, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; Lahnice Hollister and Karen Strickland, historians in South Carolina; Pat Hoerth, biographer of Evelyn Beatrice Longman; the artist Amir Bey, whose ancestor Allen Lee was Hettie Anderson’s maternal uncle; Jonathan Briffault, Dartmouth College; Alina E. Kulman, Brown University; Alexandra Ward, Yale University Art Gallery; Jennifer B. Lee, Columbia University; and Marie Southard and Alicia Smith, granddaughters of Anderson’s brother, Charles Dickerson. A version of this article appeared in The New York Times in August 2021. 2 Among the unsigned articles mentioning Anderson are a syndicated news item, “H. E. Anderson,” March 20, 1896; and “The Young Women Who Posed for the Statues on the Dewey Arch,” New York Journal and Advertiser (American Magazine), September 17, 1899, p. 7. 3 James Bone, The Curse of Beauty: The Scandalous and Tragic Life of Audrey Munson, America’s First Supermodel (New York: Regan Arts, 2016); for Nesbit, see Simon Baatz, The Girl on the Velvet Swing: Sex, Murder, and Madness at the Dawn of the Twentieth Century (New York: Mulholland Books, 2018). 4 William and Willow Hagans, Zorn in America: A Swedish Impressionist of the Gilded Age (Chicago: Swedish-American Historical Society with American Swedish Institute, 2009). 5 Kenyon Cox, Old Masters and New: Essays in Art Criticism (New York: Fox, Duffield, 1905), p. 282. 6 I base this on insights from Lahnice Hollister’s and Karen Strickland’s exhaustive research in local archives, including courthouse and cemetery records, and from decades of research by Anderson’s cousin Amir Bey. 7 Quoted in Donn Barber, “The Forty-Second Annual Convention of the American Institute of Architects,” New York Architect, vol. 3, no. 1 (January 1909), n.p. 8 Saint-Gaudens to Weinman, January 2, 1906, quoted in Hagans, “Saint-Gaudens, Zorn, and the Goddess-like Miss Anderson,” p. 84. 9 Augustus and Homer Saint-Gaudens, The Reminiscences of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Edited and Amplified by Homer Saint-Gaudens (New York: Century, 1913), p. 290. 10 Copyright I 24585, filed February 8, 1908. 11 Charles H. Dorr, “A Sculptor of Monumental Architecture: Notes on the Work of Adolph Alexander Weinman,” Architectural Record, vol. 33, no. 6 (June 1913), pp. 522–523. 12 Tranquility Cemetery, Green Township, New Jersey. 13 Daniel Chester French to Henry Watson Kent, September 15, 1917, Harriet [sic] Anderson file, Office of the Secretary Records, Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives. 14 A biography by Pat Hoerth of underappreciated Longman is in progress. 15 Anderson to Homer Saint-Gaudens, January 13, 1908, quoted in Hagans, “Saint-Gaudens, Zorn, and the Goddesslike Miss Anderson,” p. 86. 16 Hettie Anderson to William Henry Fox, June 8, 1910, box 7, folder 21, IMA Exhibition Records, Archives, Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Indianapolis, Indiana. 17 Saint-Gaudens, The Reminiscences of Augustus Saint-Gaudens, p. 332. 18 A version sold for $2,047,500 at Christie’s, New York, American Art, May 22, 2017, lot 4. 19 Coworkers described her as depressed and convinced that she was being stared at and controlled by “hostile forces.” Harriet [sic] Anderson file, Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives. 20 From Our Hut at Vao-Vai, Samoa, which Anderson purchased in March 1911 for $25 at American Art Galleries, in New York, reproduced in John La Farge, Reminiscences of the South Seas (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page, 1912), p. 258. 21 Christie’s East, Nineteenth and Twentieth Century American Paintings, Drawings, Watercolors and Sculpture, May 31, 1990, lot 257. Christie’s did not respond to numerous queries about the provenance trail. 22 Margaret F. MacDonald, The Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan and James McNeill Whistler (New Haven: Yale University Press with the National Gallery of Art, 2020).

EVE M. KAHN, former antiques columnist for the New York Times, has written a biography of the artist Mary Rogers Williams (1857–1907) for Wesleyan University Press.