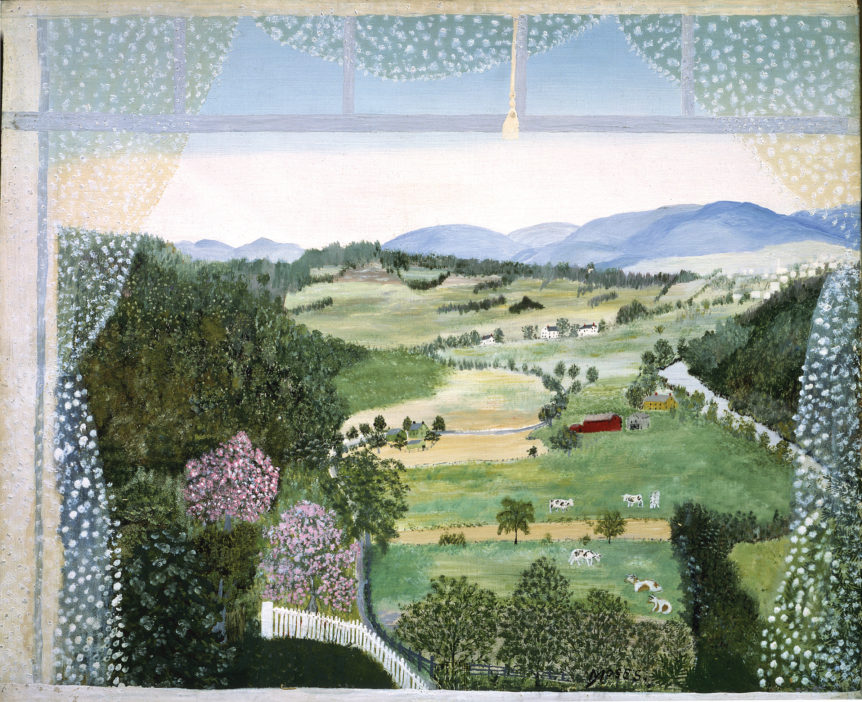

Fig. 1. Hoosick Valley (From the Window) by Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses (1860–1961), 1946. Signed “MOSES.” at lower center right. Oil on pressed wood, 19 ¼ by 22 inches. Private collection; photograph courtesy of Galerie St. Etienne, New York, © 2017 Grandma Moses Properties Co., New York, NY.

Since their introduction to the American public, Anna Mary Robertson Moses and her work have been perceived as folksy, quintessential slices of apple pie Americana. Her first solo exhibition, at the Galerie St. Etienne in October 1940, was titled What a Farm Wife Painted. Moses was an unknown artist whose appeal seemed to be rooted as much in her humble origins as in her art. Over the course of the next decade she became a celebrity, her work exhibited in museums across the country and distributed to millions of American homes via greeting cards. Today, Moses is arguably the best-known artistic autodidact of the twentieth century. Her work is often regarded as exceptional, operating outside the mainstream of art history. This perception of Moses as a self-taught naïf, disconnected from the larger culture of her time, belies a much more complex story. Moses’s work was far more in tune with the artistic zeitgeist of mid-twentieth-century America than one might imagine.

Fig. 2. Silver Coast by Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011), 1958. Oil on canvas, 39 by 41 inches. Bennington College, Vermont, © 2017 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

In a span of just eighteen months, April 1938 to October 1939, Moses’s paintings traveled from a women’s exchange at the W. D. Thomas Pharmacy in Hoosick Falls, New York, to an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art—Contemporary Unknown American Painters, curated by Sidney Janis. From its inception in 1929, MoMA had what art historian Thomas E. Crow called “a dual commitment” to European modernism and the art of the “common man” in America.1 It was from within this complex historical nexus of “folk art” and modernism that Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses was catapulted to international fame. In MoMA director Alfred H. Barr’s preface to the catalogue of the 1938 show Masters of Popular Painting: Modern Primitives of Europe and America, he stated that “the purpose of this exhibition is to show, without apology or condescension, the paintings of some of these individuals, not as folk art, but as the work of painters of marked talent and consistently distinct personality.”2 Barr’s statement of purpose is still relevant today, nearly eighty years later, as we continue the art historical struggle to break down such deeply rooted biases as the false dichotomies between “high” and “low” art, and artists who are classified as “insiders” or “outsiders.”

Fig. 3. Grandma Moses by Jean Gambotti, c. 1950. Signed “Par Jean Gambotti/52 rue Brancion/Paris, 15e/France” at lower right. Ink on paper, 8 ⅛ by 10 ½ inches. Bennington Museum, Vermont.

Fig. 4a. Clippings used as source materials for Moses’s In Harvest Time. Courtesy of Galerie St. Etienne.

While Moses entered the art world through no less an arbiter of taste than MoMA, over the course of the 1940s her exploding popularity outside the marble halls of museums and her overwhelming commercial success made her work suspect to the majority of American art critics. Most positioned Moses and her work in direct opposition to the darker, angst-ridden strains of modern art, notably abstract expressionism. Yet, she still served in many ways as the perfect symbol of a modern artist, unshackled by the expectations of the art world. Her insistence on painting “happy” pictures could be seen as unexpectedly bold in the context of a morose postwar world. Exemplifying this attitude is a caricature of Moses, sent to her by an admirer from Paris (Fig. 3). The drawing depicts Moses as a cross between a benign farm wife and a wild woman who painted on any surface she could find. The cartoon calls to mind Hans Namuth’s iconic photographs of Jackson Pollock, the other American artist taking the postwar world by storm, dancing around an unstretched canvas on his studio floor, flinging skeins of house paint directly out of the can.

Fig. 4b. Clippings used as source materials for Moses’s In Harvest Time. Courtesy of Galerie St. Etienne.

Like Pollock and other abstract expressionists, Moses had a personal, deeply felt approach to painting. Her autobiography is replete with childhood recollections built around metaphors connecting life to earth’s natural rhythms and detailed, almost transcendent descriptions of her experiences in nature. While Moses’s paintings are often referred to as “memory paintings,” seemingly factual visual records of her lived experience, it is often forgotten that she was, first and foremost, an artist, not a historian or documentarian. Her mind was occupied by the unlimited possibilities of the imagination, and she felt very little obligation to record

Fig. 4c. Clippings used as source materials for Moses’s In Harvest Time. Courtesy of Galerie St. Etienne.

“facts” in the traditional sense of the word. In an interview she clarified that while she did make careful observations of nature, her basic approach to landscape painting was deeply intuitive: “I look out the window sometimes to see the color of the shadows and the different greens in the trees, but when I get ready to paint I just close my eyes and imagine a scene.”3

Fig. 5. In Harvest Time by Moses, 1945. Signed “MOSES.” at lower left. Oil on pressed wood, 18 by 28 inches. Kallir Family Foundation, New York, © 2017 Grandma Moses Properties Co., New York, NY.

Helen Frankenthaler emerged on the national stage a few years after Moses. Her lyrical abstractions of atmosphere, personal associations, and place are often cited as the next step, after Pollock, in the supposedly linear progression of modernism.4 Frankenthaler’s approach to landscape was not all that different from Moses’s, even if the end products are markedly so. Describing the creation of her 1952 masterpiece, just three years after graduating from Bennington College, Frankenthaler recalled, “I painted Mountains and Sea after seeing the cliffs of Nova Scotia. It’s a hilly landscape with wild surf rolling against the rocks. Though it was painted in a windowless loft, the memory of the landscape is in the painting.”5 Much like Moses, Frankenthaler held the landscape inside herself and simply let it pour out, literally in her case, splashing thinned oil paints directly from a coffee can onto unprimed canvas. As much as Frankenthaler’s paintings might be built upon the memory or evocation of a specific landscape, they were equally tied up with the formal elements of art. For Frankenthaler the most successful paintings walked a tightrope, balancing pictorial depth with the flatness of the canvas. “The ‘why’ of how a picture best works for me involves how much working false space it has in depth . . . . It’s a play of ambiguities.”6 Silver Coast (Fig. 2) was painted during Frankenthaler’s 1958 honeymoon with fellow artist Robert Motherwell, and like Mountains and Sea, walks a tightrope between the suggestion of place (in this case the coast of Portugal; note the striped beach cabanas at lower left), and the formal elements of painting.

Fig. 6. Bennington by Moses, 1945. Oil on pressed wood, 17 ¾ by 26 inches. Signed “MOSES.” at lower right. Bennington Museum, © 2017 Grandma Moses Properties Co., New York, NY

Fig. 7. View of Bennington, Vermont, photographer unknown, c. 1910. Halftone-printed postcard, 3 ½ by 19 ½ inches. Moses used the postcard as a source for the painting in Fig. 6. Bennington Museum, gift of Mrs. George Atwood.

While Moses may not have been familiar with terms such as “perspectival space” or the critic Clement Greenberg’s ideas about the integrity of the picture plane, her best landscapes demonstrate that she intuitively came to similar conclusions as Frankenthaler. Moses noted, “I like to paint something that leads me on and on into the unknown, something that I want to see away on beyond,”7 simultaneously expressing her interest in drawing the viewer into a false pictorial space while emphasizing an overriding desire to convey a sense of mystery or, as Frankenthaler may have put it, ambiguity.

Fig. 8. Lehigh Canal, Sunset, New Hope, PA by Joseph Pickett (1848–1918), c. 1918. Signed “Joseph Pickett Art, New Hope PA” at lower right and inscribed “Lehigh Canal, Sunset, New Hope, PA” at lower left center. Oil on canvas, 23 ¼ by 34 inches. Pickett’s work was shown in nearly all of the earliest museum exhibitions of American folk art in the 1930s, including the 1938 show Masters of Popular Painting: Modern Primitives of Europe and America at the Museum of Modern Art. Private collection; photograph courtesy of Galerie St. Etienne.

In paintings like Hoosick Valley (From the Window) (Fig. 1), Moses’s delicate, atmospheric transitions of color, from rich forest and vivid grassy greens in the foreground to softer minty and sage greens in the middle ground, melting into the soft blues of the background hills and sky, combine with the complex topography of Washington County’s rolling hills, dropping steeply downward into the river valley below before rising precipitously to a relatively high horizon line, to create a complex, slightly baffling effect of simultaneous depth and flatness.

Fig. 9. American Homestead—Summer, published by Currier & Ives, 1869. Hand-colored lithograph, 10 1/8 by 13 ½ inches. Moses used the print as a source for her Old House at the Bend of the Road. Shelburne Museum, Vermont, gift of Rush Taggart; photograph by Andy Duback.

While the subjects of Moses’s paintings often held deep personal significance, she was outright omnivorous when it came to stealing preexisting imagery for her work, echoing Picasso’s famous quip, “When there’s anything to steal, I steal.”8 The means by which Moses incorporated these sources into her paintings are complex and visually sophisticated. Some Moses paintings, such as The Old House at the Bend of the Road (Fig. 10), are based directly on Currier & Ives lithographs (Fig. 9) with expected adjustments to color and the substitution or addition of a new figure here or tree there. Far more interesting and aesthetically successful was Moses’s more common practice of cobbling her paintings together from many sources, rarely identifiable, into cohesive, balanced wholes. The majority of her paintings depend heavily on images taken from popular periodicals such as the Saturday Evening Post (Fig. 12), greeting cards, postcards (Fig. 6), chromolithographs, or just about any other image that passed through her hands. The majority of the people, animals, and buildings—and even some of the landscape elements—in her paintings were directly traced or adapted in some form from preexisting imagery. All that mattered to Moses was that the images carried associative qualities that stirred her memories and imagination. The most common method Moses used to transfer these images to her paintings was to directly trace them with pencil over carbon paper onto the pristine white surface of a prepared Masonite board. Rather than traditional pasted paper collage, this technique might be better called “uncollage,” a sort of reverse engineering that combines multiple unrelated image sources into a cohesive painted whole, leaving little trace of their disparate origins.9

Fig. 10. The Old House at the Bend of the Road by Moses, c. 1939. Oil on oilcloth, 10 ¾ by 12 ½ inches. Bennington Museum, gift of Sylvia Partridge, © 2017 Grandma Moses Properties Co., New York, NY.

Bringing together myriad unrelated clippings to make distinct new images echoes the practice of another of America’s best-known self-taught artists of the mid-twentieth century, Joseph Cornell. Though typically understood to be an integral member of America’s artistic avant-garde, Cornell, like Moses, came to his practice completely independent of any formal training. The introduction of surrealism to America, largely through the Julien Levy Gallery in New York, where Cornell first exhibited his work, provided a framework to understand Cornell’s assemblages of found objects and images as “fine” art. Though best known for his boxed constructions, found-image collage formed a critical aspect of Cornell’s artistic practice through much of his career. Cornell kept his source materials filed in his basement studio in some 150 loosely categorized, highly personal dossiers, which he described as “a diary journal repository laboratory, picture gallery, museum, sanctuary, observatory, key . . . the core of a labyrinth, a clearinghouse for dreams and visions . . . childhood regained.”10 This poetic description echoes Moses’s less-structured system: a wooden trunk filled with unsorted clippings that she would riffle through to find inspiration.

Fig. 11. Catchin’ the Turkey by Moses, 1955. Signed “MOSES.” at lower left. Oil on pressed wood, 12 by 16 inches. Bennington Museum, © 2017 Grandma Moses Properties Co., New York, NY.

One of Cornell’s collages, created for the cover of a special thematic issue of the avant-garde arts magazine View (Fig. 13), published in January 1943, is particularly consonant with Moses’s work. The overarching theme of the issue was “Americana Fantastica,” and like Moses’s paintings, Cornell’s collage draws on familiar tropes of resonant, stereotypical American imagery. Unlike Moses’s work, the jarring juxtapositions are intended to be provocative and to create both visual and psychological tension as well as humor. Occasionally, Moses also created the humorously surreal image, such as Horseshoeing (Fig. 16), with its speeding train and horses headed full-tilt toward a group of stationary figures only a few feet away. Cornell allowed his source material to speak for itself, pasting his cutouts directly, often onto a larger found landscape image or other found surface, without alteration beyond their re-contextualization. Moses, on the other hand, dramatically altered and abstracted the source material in her borrowings. She transferred only their bare outlines, which she then painted over in loosely applied strokes of color, obliterating any illustrative detail while maintaining the original source’s associative quality. The real magic in Moses’s paintings is that she was able to pull together such disparate images into cohesive, reassuring wholes, as though they were always meant to be together, as though they were her own memories.

Fig. 12. Clipping from the cover of the Saturday Evening Post, August 18, 1951, showing a detail from Evening Picnic by John Philip Falter (1910–1982) that Moses used in Catchin’ the Turkey. Courtesy of Galerie St. Etienne.

Moses was a toddler when Édouard Manet painted Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1863) and died just as Andy Warhol’s work ushered in postmodernism. Her life spanned the entire history of modern art, and in many ways her work anticipated ideas about appropriation, commercialism, and the manufactured nature of nostalgia that would take the art world by storm in the decades that followed. As unlikely a comparison as it may seem, Warhol (Fig. 14), who was a major collector of folk art and served on the board of the American Folk Art Museum in New York, had a surprising amount in common with Moses. Beginning his career as a commercial illustrator in the 1950s, he was just as voracious as Moses in “stealing” and adapting his imagery from popular printed sources. Given his penchant for celebrity and the intersection of art and commercialism, it is hard to imagine he wasn’t drawn to Moses’s work, shown at the prestigious Carnegie International exhibitions in his hometown of Pittsburgh every year from 1945 to 1950 and printed on plates and fabrics used to decorate homes throughout America in the 1950s.11 This is not to make a claim of direct influence; rather, it is astounding how resonant Moses’s practices were with larger trends in the art world, and how little it has been noted.

Fig. 13. Americana Fantastica, cover of View, 2nd ser., no. 4 (January 1943), designed by Joseph Cornell (1903–1972). Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute Library, Williamstown, Massachusetts; photograph by Michael Agee, © 2017 Visual Artists and Gallery Association (VAGA).

Moses’s art didn’t take part directly in the intellectual underpinnings of modernism or postmodernism, yet her work is modern, is postmodern, without trying to be. After the craze for “primitives” in the 1930s and ’40s, the works of Moses and others like her were positioned outside the supposedly linear progression of modernism proper, not significant in their own right but as inspiration for mainstream, avant-garde artists. Art historian Donald Preziosi, in a catalogue essay for the groundbreaking 1992 Los Angeles County Museum of Art exhibition Parallel Visions: Modern Artists and Outsider Art, which looked at the relationship between so-called insider and outsider art in the twentieth century, posited an approach in which “modernism is expanded beyond the interlinked series of avant-gardist practices canonized by art history and museology,” wherein “all manner of artistic practices become, in effect, part of the ‘story’ of modernism.”12 With this look at Moses’s own artistic practice, I hope we can begin to understand her not as an anomalous self-taught, folk superhero but as a real contributor to the story of American art of the twentieth century. Moses created visually sophisticated paintings that melded her memories of growing up in rural, nineteenthcentury America with her more recent experiences in an increasingly modernized, homogeneous America, saturated with printed images that often drew upon nostalgic tropes of a romanticized golden age that was just beyond the direct experience of most viewers. Built on a foundation of selective memory and the associative power of popular imagery, her paintings have become a part of America’s collective consciousness, providing viewers an eternally longed-for “promised land” ever since they made their way beyond the boundaries of Washington County, New York, nearly eighty years ago.

Fig. 14. Untitled from Flowers portfolio by Andy Warhol (1928–1987), 1970. Color screen print on paper, 38 inches square (sheet). Warhol’s Flowers series was derived from a photo of hibiscus blossoms published in the June 1964 issue of Modern Photography. The artist simply cropped and adapted the image to his own needs. His techniques for appropriating such popular imagery were surprisingly similar to Moses’s creative process, even if their intentions and end results differed significantly. Williams College Museum of Art, gift of the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, © 2017 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Grandma Moses: American Modern is on view at the Bennington Museum from July 1 to November 5. The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue published by Skira Rizzoli.

Fig. 15. Métropolitain by Fernand Léger (1881–1955), 1949, from Arthur Rimbaud, Les Illuminations (Grosclaude, Éditions des Gaules, Lausanne, 1949). Signed “F.L” at lower right. Lithograph with watercolor; 13 by 9 ⅞ inches (sheet). Leger, who was an early innovator of cubism and whose work was included in Alfred H. Barr Jr.’s 1936 exhibition at the Modern Museum of Art, Cubism and Abstract Art, was also a strong proponent of American folk art. He claimed the paintings of Edward Hicks and Joseph Pickett were some of the strongest works he saw during his time in America. Williams College Museum of Art, anonymous gift, © 2017 Fernand Léger Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

1 Thomas E. Crow, The Long March of Pop: Art, Music, and Design, 1930–1995 (Yale University Press, New Haven, 2014), p. 7. 2 Alfred H. Barr Jr., “Preface and Acknowledgment,” in Holger Cahill et al., Masters of Popular Painting: Modern Primitives of Europe and America (Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1938), p. 9. 3 Quoted in “Art:as Grandma’s Imaginings,” Time, vol. 52, no. 10 (September 1948), p. 42. 4 Henry Geldzahler, “An Interview with Helen Frankenthaler,” Artforum, vol. 4, no. 2 (October 1965), p. 37. 5 Quoted in John Elderfield, “The Pleasure of Not Knowing,” in Painted on 21st Street: Helen Frankenthaler from 1950 to 1959 (Gagosian Gallery, distr. Harry N. Abrams, New York, 2013), p. 9. 6 Quoted in Gene Baro, “The Achievement of Helen Frankenthaler,” Art International, vol. 11, no. 7 (September 20, 1967), p. 36. 7 Jane Kallir, Grandma Moses in the 21st Century (Art Services International in association with Yale University Press, New Haven, 2001), p. 221. 8 Quoted in Françoise Gilot and Carlton Lake, Life with Picasso (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1964), p. 317. 9 The term “uncollage” was coined by the artist and curator Todd Bartel. See Todd Bartel, “Bo Joseph: Attempts at a Unified Theory,” csw.org, published September 7, 2010. 10 Charles Simic, Dime-Store Alchemy: The Art of Joseph Cornell (New York Review of Books, New York, 1992), p. 37. 11 Email correspondence July 28, 2015, and conversation, August 4, 2015, with Blake Gopnik. I’d like to extend my thanks to Gopnik for sharing some of his yet-to-be-published biography of Warhol with me and noting the fact that Warhol would have undoubtedly seen Moses’s work at the Carnegie Internationals during the second half of the 1940s. 12 Donald Preziosi, “Art History, Museology, and the Staging of Modernity,” in Parallel Visions: Modern Artists and Outsider Art, ed. Maurice Tuchman and Carol S. Eliel (Los Angeles County Museum of Art in association with Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 1992), p. 304.

Fig. 16. Horseshoeing by Moses, 1960. Signed “MOSES.” at lower left. Oil on pressed wood, 16 by 24 inches. Collection of Harry L. Moses and the estate of Roy W. Moses; photograph courtesy of Bennington Museum, © 2017 Grandma Moses Properties Co., New York, NY.

Jamie Franklin, the curator at the Bennington Museum, was co-curator, with Thomas Denenberg, director of the Shelburne Museum, of Grandma Moses: American Modern. This article is adapted from his essay in the exhibition catalogue.