Difficult times for the American Folk Art Museum went public in 2011, when its building, a gem by the architects’ Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, was sold to the Museum of Modern Art. Despite much vocal opposition, MoMA eventually reduced that gem to rubble in 2014, making way for nothing comparable on 53rd Street. So much for the legacy of the brave little folk art museum? Not at all. Even during its darkest days, the museum soldiered on with solid exhibitions in its tidy galleries at 2 Lincoln Square, and then, in 2015, roared back with something more surprising, pathbreaking, and revelatory than anything MoMA can claim to have done. When the Curtain Never Comes Down blew apart a lot of conventional categories, including those of performance and even outsider art (see Ricardo Resende et al., “Disturbers of the peace: A selection of artists from the American Folk Art Museum’s When the Curtain Never comes Down,” The Magazine ANTIQUES, July/August 2015). Its twenty-seven artists, mostly unknown (and not collectible) enacted their creations in clothing, music, film, audio recordings, and other mediums, unsettling our responses, accustomed as we are to recognizable categories and the comfort they give us. These were public displays of private obsessions, performances that entranced, moved, puzzled, and thrilled. It was a gas.

These artists do not “manage” their stigma; they enact it, and that is bound to fascinate as we each find works that touch on us. This is, I think, what art brut, and especially Photo Brut, can be about

The force behind that exhibition was Valérie Rousseau, who joined AFAM as curator of twentiethcentury and contemporary art in 2013. Five years and several notable exhibitions after Curtain, Rousseau has mounted a companion piece of sorts, Photo Brut, work by some forty contributors from several countries whose uses and abuses of the camera fit the criteria of art brut as defined by Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985) as lying outside recognizable precincts of academic art (though it should be noted that Dubuffet was not interested in photography). Drawn primarily from the collection of the French filmmaker and collector Bruno Decharme, who brought Rousseau in as a partner for the initial 2019 exhibition in Arles, Photo Brut is not a survey according to Rousseau, but simply a first look at this material. The impressive catalogue, with its sophisticated typography and homemade touches (rough cardboard covers), contains an appealing interview with Decharme as well as enough French theoretical flourishes here and there to grace a Festschrift for Roland Barthes. While it serves as the catalogue for AFAM’s exhibition, there are some notable differences between the two shows.

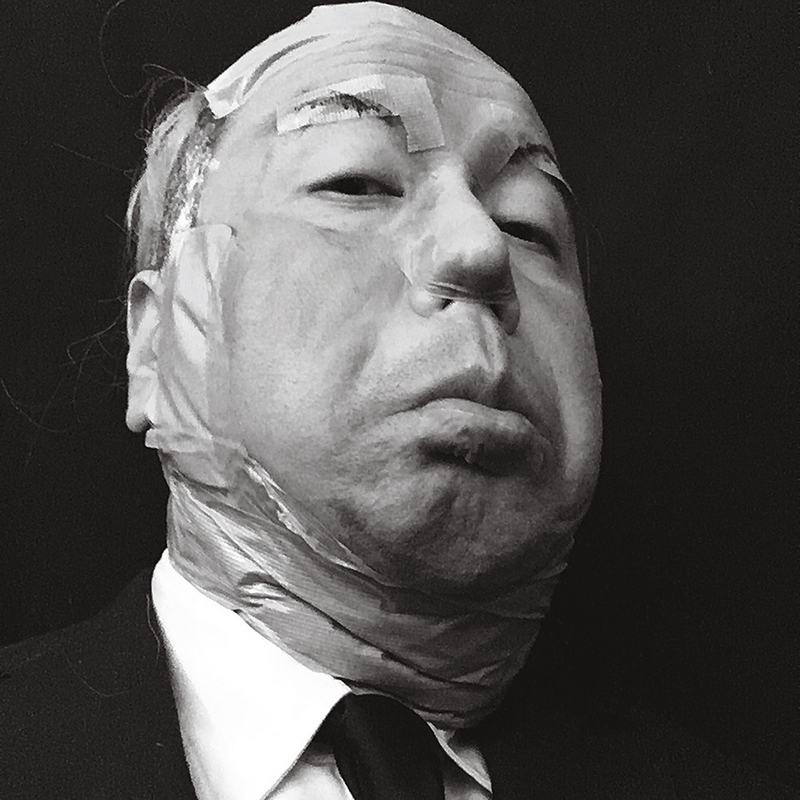

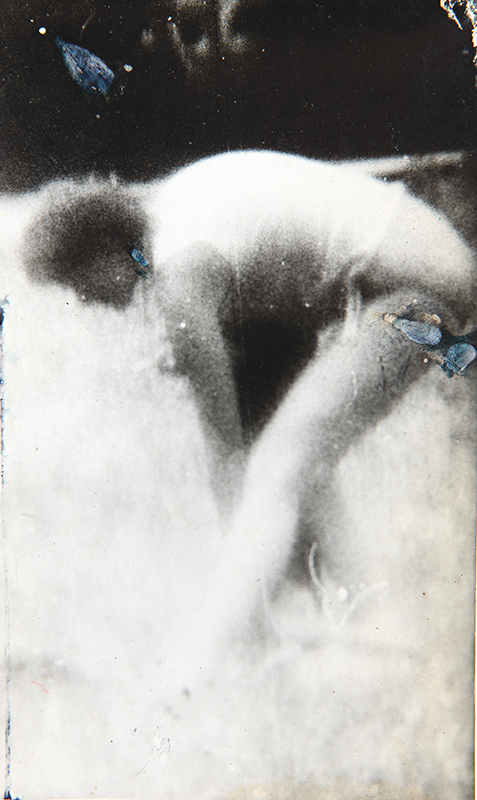

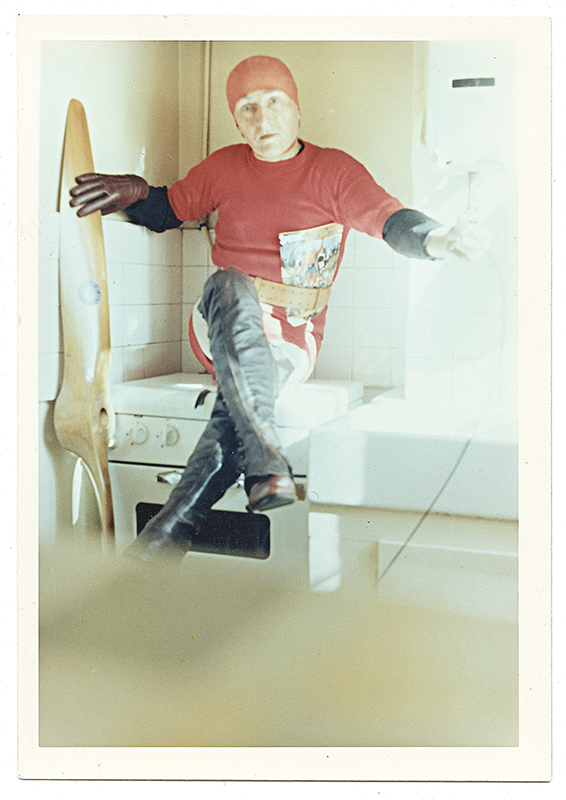

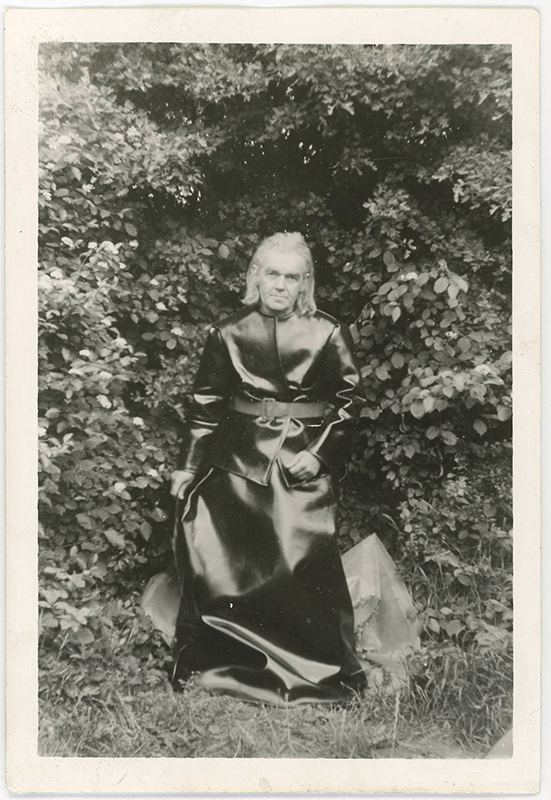

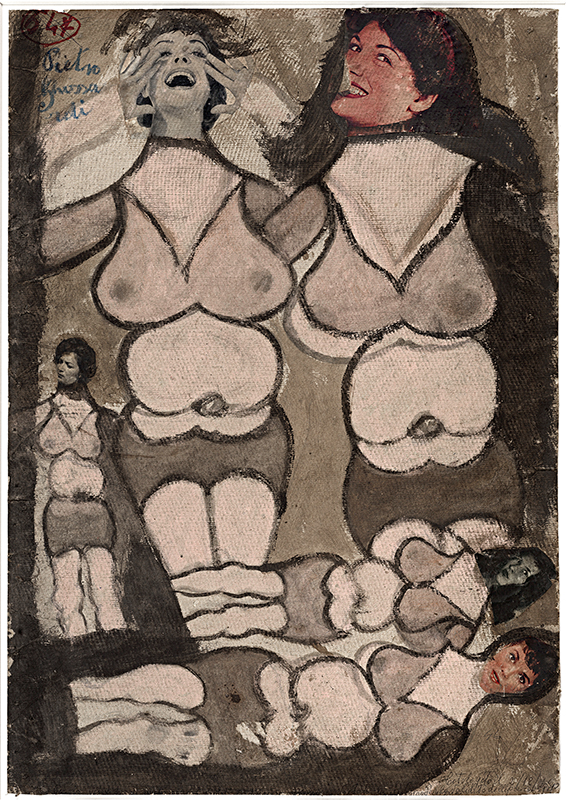

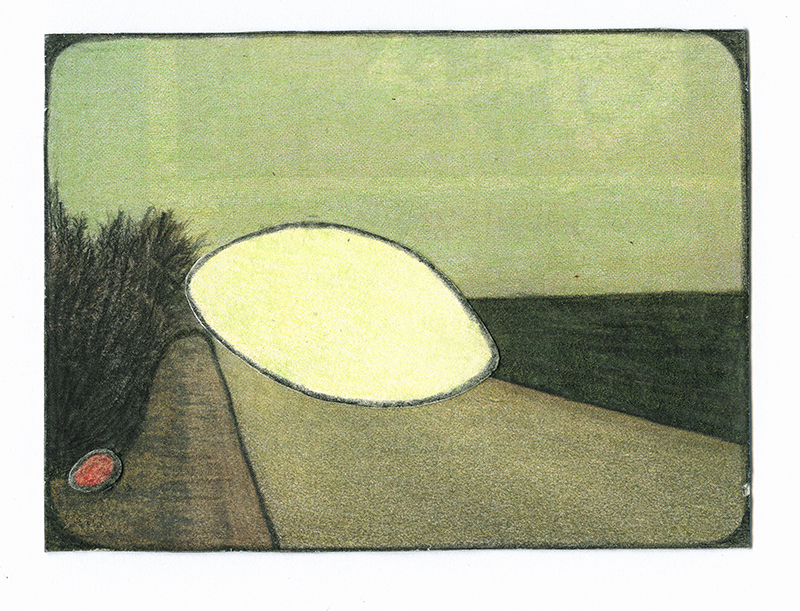

The AFAM version omits ten or so of the artists seen in Arles, while adding works from its own collection (more pieces by Eugene Von Bruenchenhein, Lee Godie, and others) as well as some from private collectors and other institutions. The wall labels are succinct renditions of the catalogue copy, and the four categories into which this vast assemblage of some four hundred works were arranged have been retained: “Performing” (stagings, role playing), “Private Affairs” (explorations of sexuality and desire), “Reformatting the World” (transformations of received images), and “Conjuring the Real” (spirit photographs and other images of paranormal phenomena). That these categories will seem to overlap and possibly contradict one another will be an inevitable response of some visitors. That’s as it should be. As Valérie Rousseau observes, nothing about this exhibition resembles the experience of attending a traditional photography show. Nor is it meant to.

Fig. 5. Pose 3, 29 mai 71 by Marcel Bascoulard (1913–1978), 1971. Gelatin silver print, 5 1/8 by 3 ½ inches. American Folk Art Museum; photograph courtesy of Galerie Christophe Gaillard, Paris.

Fig. 6. Untitled by Lee Godie (1908–1944), c. 1950. Gelatin silver print, 4 ¾ by 3 ¾ inches. Collection of Kevin O’Rourke; photograph by Adam Reich.

What exactly are we looking at? For anyone who winces as I do when people tiptoe around the issue of pathology in art brut, Bruno Decharme is refreshingly forthright. Acknowledging the subjectivity of his collection—some works speak to him while others do not—he wades right in with this definition: “the category of brut photography comprises pictures, prints, photomontages, and photocollages made by creators outside the art world and conventional art circuits, who live in a mental institution or in solitude and marginality.” Rousseau sheds especially welcome light when she characterizes the works in the Performing section as “unironic,” formulations of “something that is both unsayable and simultaneously very close.” I think that observation applies to much of what we see in all four sections—and our responses to seeing it.

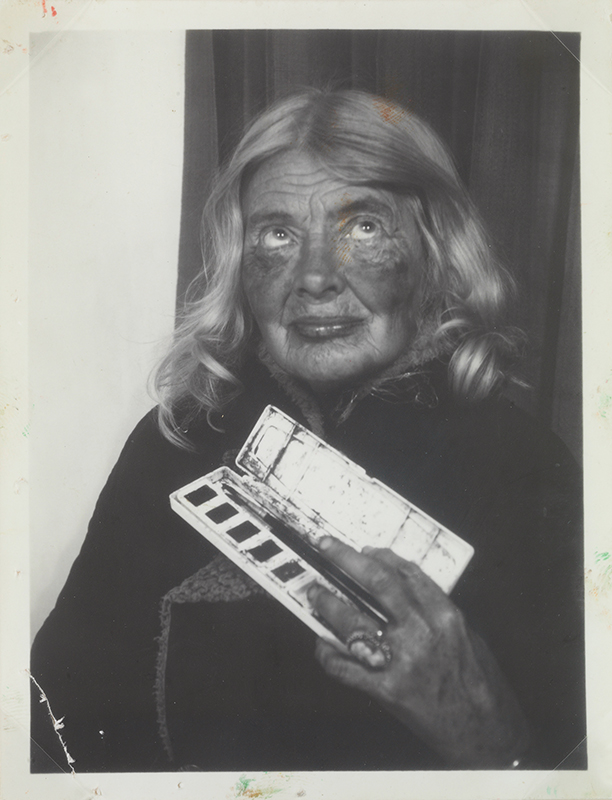

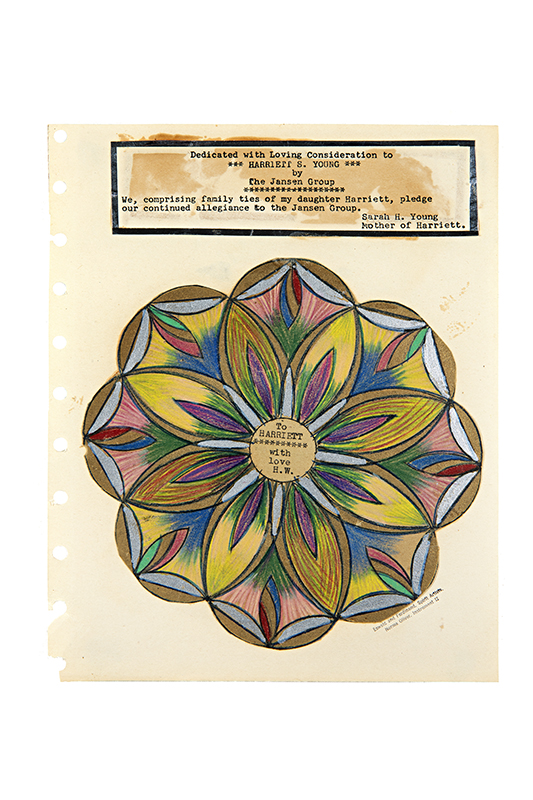

Fig. 7. Dedicated with Loving Consideration to Harriett S. Young by the Jansen Group by Norma Oliver (1893–1979), 1947. Colored pencil on paper with collaged typed inscriptions, 10 5/8 by 8 ¼ inches; and gelatin silver print 9 3/8 by 6 7/8 inches. Decharme Collection; photograph by Ilan Weiss.

So hang on to that last phrase about the “unsayable” as well as to Decharme’s criterion of subjectivity as a license to take your own ride through this exhibition. In the spirit of art brut we should all be free to overturn and/or improvise on the categories arranged here, to turn away from some works, embrace others. Doing so as I paged through the catalogue helped me to approach the question of whether we should be trespassing on these lives and their private ways with reality to begin with. After all, some of this work was not meant to be seen. Miroslav Tichy, for instance, was especially emphatic that he did not want his photographs of women in public places exhibited—although they were shown more than once in his lifetime (Fig. 2). And even when the work is made public, as in Ichiwo Sugino’s photographs of his altered face posted on Instagram (Fig. 1) or the self-portraits that Lee Godie sold outside the Art Institute of Chicago (Fig. 6), do we deform their private imperatives with our gaze?

If so, what excuses our trespass? I think what redeems the whole enterprise of collecting and viewing these photos comes with the small shocks of recognition we each may experience here and there. These works are by artists who have been stigmatized in one way or another and have turned to the healing property of artistic self-expression. It is my view that they may call forth in us a certain recognition. After all, as the sociologist Erving Goffman has pointed out, we are all stigmatized in small (or large) ways that we conceal or manage during the rituals of everyday life. These artists do not “manage” their stigma; they enact it, and that is bound to fascinate as we each find works that touch on us. This is, I think, what art brut, and especially Photo Brut, can be about, as these artists successfully liberate art-world codes, categories, and clichés along with themselves, and perhaps us.

For all the rule-breaking surprises of Photo Brut, the exhibition is undeniably white and male, which is no doubt why Rousseau is emphatic that this is only a first look at what must be a vast body of work as yet uncollected and unexplored. When I ask her why, out of some forty artists, there are only four women, she suggests that greater shame and thus isolation may attend women’s status as outsiders, which is, I suppose, another way of saying that women may have been socialized to manage their stigma differently, less overtly, than men. Whether that is true, and whether it is true for nonwhites as well, will be a matter to be seen and explored eventually. In the meantime, as we experience the work of artists responding to difficult personal imperatives, we have been liberated to recognize our own.

Photo Brut: Collection Bruno Decharme and Compagnie is on view at the American Folk Art Museum in New York City from January 24 to June 6.