We have all heard stories about the little one-room schoolhouses where education was provided in the earliest years of the American Republic. Attendance was voluntary and many children rarely came to learn. Boys generally went to school during the winter months, when their labor was not needed on the family farm. Strict schoolmasters kept the boisterous boys busy with memorizations and, when an error was made, responded with either physical punishment or the humiliation of a dunce cap. Girls were often only allowed to attend the local school during the summer, when reading was taught, but not writing. Additionally, some towns reduced their school costs by having the girls taught by untrained women, instead of educated male schoolteachers. The prevailing belief was that a woman had an essential domesticity and that educating girls would rob them of a content mind and their feminine charms.

At the time of the American Revolution, many adult white men were close to being illiterate, or perhaps only able to read from the Bible. It has also been estimated that up to half of all women at the time had difficulty even signing their name to documents. Education initially remained as it had been in colonial times, with the notable exception of a few communities, such as the Quakers or the Pennsylvania Germans, who emphasized the teaching of both boys and girls. Increasing taxes to pay for better schools was sometimes so vehemently rejected that it resulted in stories of the tax collector being tarred and feathered.1

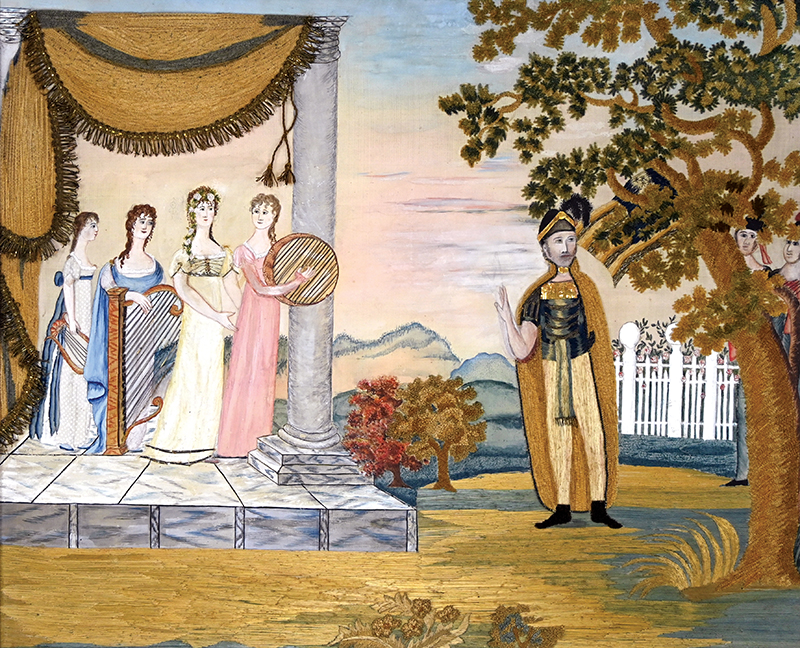

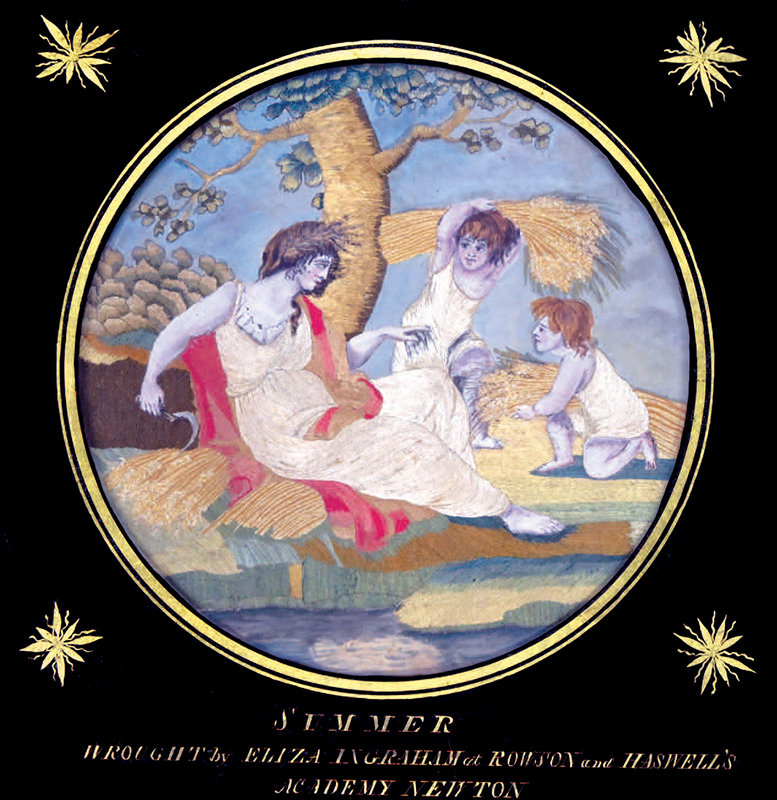

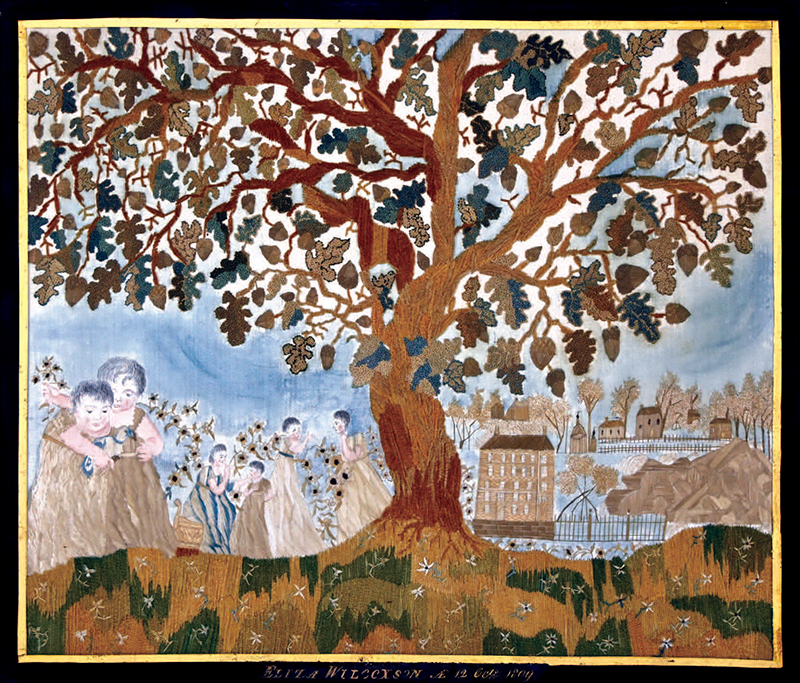

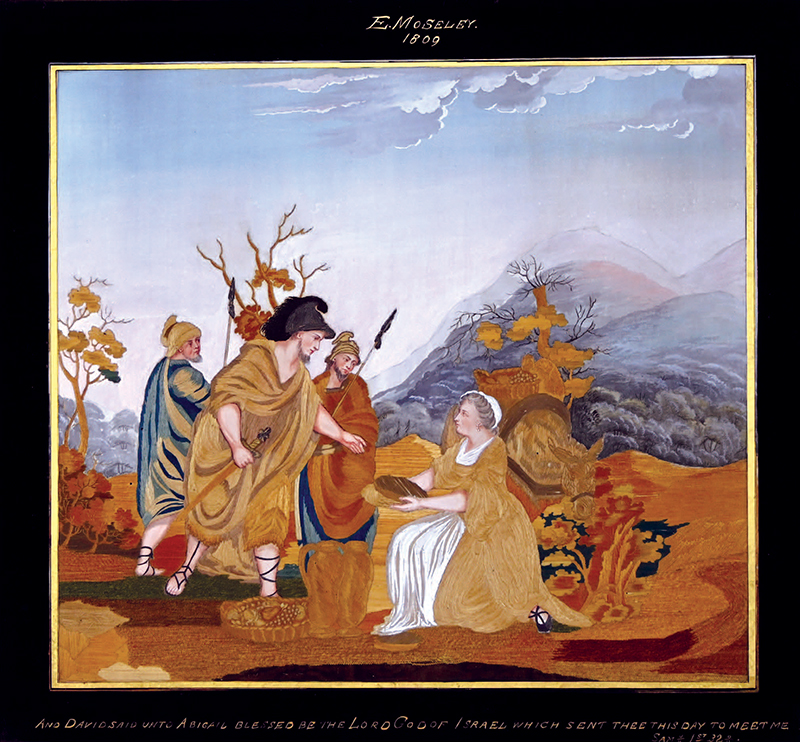

However, if one attends a major American antiques show, or visits a museum with a collection of early American artifacts, exhibited on the walls will be artistic creations that illustrate a very different view of the changes and improvements in education that occurred during the early years of the United States. On display will be extraordinarily intricate and impressively large silk-on-silk pictorial embroideries and memorials that were produced by American schoolgirls between 1790 and 1830 (Figs. 1–4). Why, just a few years after the revolution, did young women, generally between the ages of fourteen and twenty-one, create these highly elaborate embroideries? How were large numbers of young women able to produce objects that required up to a year of labor using expensive silk imported from China? And why did the embroideries often depict scenes from Greek and Roman mythology, which would have been so remote from their own lives?

These embroideries were the product of the new academy schools that grew out of an emerging emphasis on education and its transformative powers. Starting in the 1790s, hundreds upon hundreds of private academies that charged tuition were organized throughout the country to provide education beyond that offered in the local public schools. American education became a blend of public schools for elementary learning, private academies for advanced studies, and colleges for the training of physicians, lawyers, and the clergy. Literacy was enhanced by slowly introduced educational reforms including age-based teaching, textbooks authored by Americans, encouraged regular attendance, and the beginnings of formal teacher training. America changed within a single generation into a country with almost universal literacy in the white adult population.

Many academies were started by community leaders in a burst of public spirit, while some were business enterprises begun by teachers or ministers who were often encouraged to establish a school for the prestige and opportunity it would bring to a community. Although paying for this education often stressed even a middle-class family’s finances, private academies became the centers for advanced learning and were seen as a pathway to success and higher socioeconomic standing. In 1790 the median age in America was just under sixteen years, allowing many students to be affected by these new educational opportunities. Samuel Whiting, who wrote a popular reading guide for young ladies’ academies, expressed in 1820 this novel sentiment: “The foundation of knowledge and virtue is laid in our childhood. . . . It is education that makes the man, or the woman.”2 In 1815 Baltimore’s Niles’ Weekly Register rejoiced at the development of an “almost universal ambition to get forward.”3 The academies helped foster the transformation into a literate population that was able to participate in the commerce, politics, and dynamic changes that occurred during the early nineteenth century.

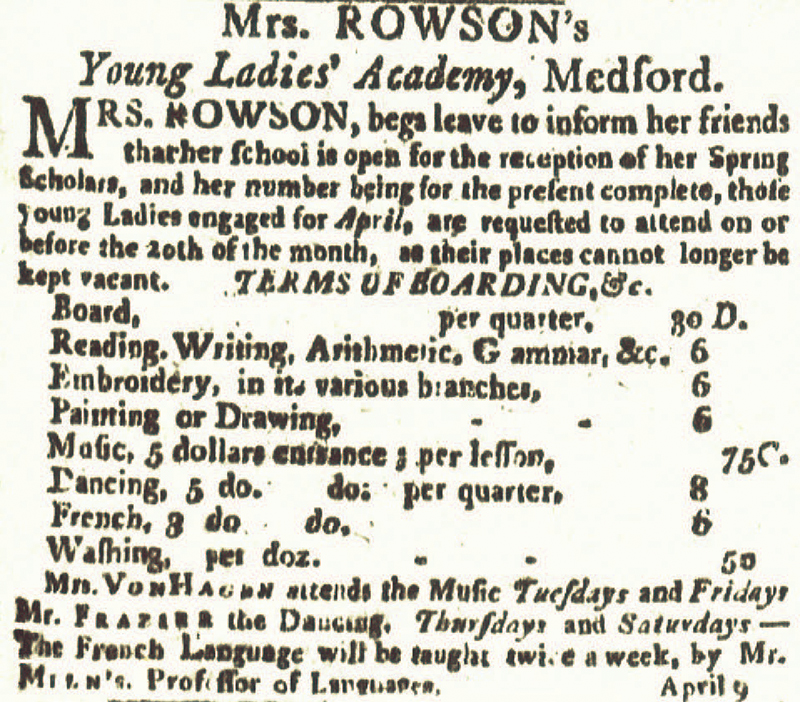

While some academies accepted both girls and boys, perhaps a majority were young ladies’ academies that were often opened and run by enterprising women teachers. Fifty-five women advertised their academies between 1800 and 1830 in Boston newspapers.4 This represented the first time that organized advanced education was available to American women. One commentator in Philadelphia wrote in 1810 that an “astonishing revolution of sentiment and practice with respect to the education of women has, of late, been accomplished in America.”5 The cost to educate young women was considered to be justified as it would result in a “Republican motherhood,” whose dignified and educated character would uphold the spiritual and moral guardianship of the family and be passed on to the men and children in their lives.6

Although all children, under the newly evolving system, were taught similar basic academic subjects, a boy’s education would often include navigation, Greek, and Latin, while girls were taught ornamental arts such as needlework, music, and drawing to enhance their gentility and taste. Benjamin Rush’s Thoughts on Female Education, published in Philadelphia in 1787, suggested that women’s education should concentrate on the useful branches for their future roles as wives and mothers.7 Printed sermons, such as one by Reverend John Bennet published in 1792, provided the guidance that the “accomplishments of a woman, may be comprised under some, or all of the following articles; needle-work, embroidery, &c. drawing, music, dancing, dress, politeness, &c. To weild [sic] the needle with advantage, so as to unite the useful and beautiful, is her particular province, and a sort of ingenuity, which shows her in the most amiable and attracting point of view.”8 Another commentator noted that with education, a woman’s “refinement of manners, and a cultivated mind” gained numerous benefits, and, that by attending an academy, “you will see the best of good breeding . . . a preciseness, and affection of manners.”9

The young ladies’ academies offered an extensive curriculum of academic and ornamental art classes (Fig. 5). Mrs. Saunders and Miss Beach’s academy in Dorchester, Massachusetts, advertised in 1819 that instruction was given in “reading, writing, arithmetic, ancient and modern geography, astronomy, use of globes, history, rhetoric, botany, composition, English and French,” and, at an extra cost, in the ornamental arts, including “drawing, painting in oils, crayon and watercolors, painting on velvet, ornamental paper work, drawing, coloring maps, plain sewing, tambour work, and needlework” (Fig. 7). Music and dancing instruction were also available, and the students had the use a library with more than fifteen hundred volumes.10 Along with local pupils, the more prominent young ladies’ academies regularly attracted students from distant towns and even different states. They boarded either in the academy building with the headmistress or with trusted local families.

In Connecticut, Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy emphasized grammar, composition, rhetoric, and reading, as well as geography and history. Students were required to write compositions examining a woman’s proper traits and abilities, as well as to read and discuss a wide range of books. During the many hours spent each week embroidering (Fig. 10), students read aloud from the texts illustrated in their embroideries and listened to serious discussions on many topics. As John Pierce Brace, who succeeded Sarah Pierce as head of the school, wrote: “Our object has not been to make learned ladies . . . . there is a more useful, though less exalted and less brilliant station. . . the education for time and eternity of the next generation.”11

While intricate embroideries by American women from earlier in the eighteenth century are found in small numbers, the young ladies’ academies produced a crescendo of needlework.12 In the majority of schools, samplers and memorials of varying quality were produced. However, complex silk-on-silk pictorial embroideries were generally the products of the more prominent academies in the larger towns, where the headmistress or a teacher was highly skilled in needlework techniques and could provide the extensive individual guidance needed by each student.

Examination of unfinished embroideries reveals the sequence of tasks required in their production. A piece of silk was first tightly stretched over a wood frame and the design was drawn on it. The images most commonly chosen were from classical mythology, scripture, and contemporary literature, with an emphasis on stories containing a strong moral message, extolling the joy of education, or emphasizing the inner strengths of woman (Figs. 11–13). Scenes from the classical world were particularly popular, as the republics of antiquity were often seen as inspirational models for the new American nation (Figs. 14–17). The young women became immersed in the stories and the aesthetic qualities of the needlework they were embroidering.

The sources for these images included prints and book illustrations, patterns laid out by professional artists, and designs made by the girls themselves (Fig. 18). In Philadelphia, Samuel Folwell and his son Godfrey were artists with a large business designing and painting the embroideries for their family’s academy as well as several other schools in the Philadelphia area (Fig. 19).13 Charles Codman advertised in Portland, Maine, in 1823 that he did “Drawings for Ladies Needlework, also figures and sky colored for the same.”14 Some academy teachers even noted in their advertisements that they had studied with professional artists to enhance their ability to teach art.

Silk thread dyed in a dazzling array of colors was used for the embroidery, along, occasionally, with wool, hair, metallic foil, sequins, pearls, velvet, and other materials. A variety of stitches, some surprisingly intricate, produced differing textures and patterns, resulting in a complex and highly enriched surface. The impression of a depth of view was created by using warm, brighter colors in the foreground and cooler, darker colors in the distance. Perspective and volume were further conveyed by overlapping objects, trees, and hills in conjunction with modulations of color. The individual approach of each academy’s teacher to the embroidery of her students makes it possible to attribute examples to several different schools.

Each embroidery, composed of thousands of stitches, required immeasurable patience and many months of effort. At the same time, the students were also attending academic courses. The portrait painter Susanna Paine described in her autobiography how she was able to pay for her own education by helping other girls with their embroideries in her spare time.15 The exquisite workmanship that is the hallmark of almost every embroidery demonstrates their importance to the students.

Faces, the sky, and other details in the composition were painted in watercolors, often by the experienced teacher or by a professional artist. The individual style of painting, particularly in the depiction of the faces, sometimes allows for an attribution to a particular academy or artist. Many artists advertised that they did this specialized work, such as John Roberts, who in 1803 in Portland, Maine, offered to paint “all kinds of FANCY and EMBROIDERY WORK for schools and individuals.”16

Framing of the finished embroidery was commonly done in an elegant style. The needlework was often placed behind glass with a reverse-painted black border edged in gold—creating a formal theatrical proscenium—which sometimes included inscriptions, such as the girl’s name, the scene’s title, date of completion, or the academy’s name. This was then placed into a gold-leafed frame. Newspaper advertisements for the framing of needlework were regularly published. Louis Lemet had a framing shop in Albany, New York, where he advertised in 1810 that for patrons “who may please him with the framing of NEEDLE WORK, he offers to PAINT THE HEAD GRATIS.”17 On occasion, the framer’s label has remained on the embroidery’s back and provides valuable information about the location where it was made.

An 1813 invoice from Lydia Bull Royse’s academy in Hartford, Connecticut, to a young girl’s father charged $7.62 for fourteen weeks’ tuition and $27.00 for twelve weeks of board, while her embroidery costs were $2.12 for drawing the design, $5.09 for silk, and $5.50 for painting the picture.18 The needlework’s expense totaled $12.71, almost double the cost of her tuition, and the embroidery still had to be framed.

Many young ladies’ academies had public commencement exercises and exhibitions. The students demonstrated their skills in rhetoric and performed in short plays, while their embroideries, penmanship, and drawings were proudly displayed. Large public crowds often attended these events, and the local newspaper published details. This demonstrated the academy’s success with its students and enhanced the public prominence of the school.

Each girl returned home with her embroidery, where it would be proudly displayed. It was the equivalent of a diploma that announced her artistic and practical skills as well as her advanced education. The work affirmed and symbolized her feminine accomplishments, including knowledge, superior taste, and gentility. Here was a well-educated and discerning young woman who would make an ideal companion for both the heart and mind in a marriage.

In the period from 1790 to 1830, silk-on-silk pictorial embroideries were artistic creations that were the height of fashion, bringing a new level of conceptual dramatization to the walls of American homes. These three-dimensional illusions created a realistic spatial perspective that far exceeded those found in portraits or prints. They also presented the viewer with the engaging challenge of understanding and participating in the illustrated story—absorbing its moral message, enjoying depictions of exotic places and dress, or reveling in scenes of heroic drama. An embroidery’s vivid colors and varying textures would shimmer and shine in the flickering light of the fireplace. Each visitor to the home would examine, discuss, and admire the embroidery and the young woman who made it. As an object to delight the eye and engage the mind of a viewer, a silk-on-silk pictorial embroidery was as captivating then as virtual reality is to us today.

The aesthetic influence of silk-on-silk embroideries was deep and wide-ranging. American artist John Trumbull remembered how his older sister’s needlework affected him: “These wonders were hung in my mother’s parlor, and were among the first objects that caught my infant eye. I endeavored to imitate them.” As an older man, he related that his experience with these embroideries set the course of his life in a direction far away from the legal career his father insisted he undertake.19

During the 1820s, and continuing into the 1830s, there were numerous calls for the young ladies’ academies to stop spending their students’ time on ornamental achievements. It was argued that the production of these large embroideries was frivolous and that schools should be teaching a curriculum solely focused on improving a girl’s mind. When Lydia Huntley opened her Hartford, Connecticut, young ladies’ academy in the 1820s, she omitted teaching ornamental subjects at the request of the girls’ parents.20 Over the next few years, the production of elaborate pictorial embroideries gradually came to an end.

The elegance and artistry of American silk-on-silk pictorial embroideries from the early years of the nineteenth century reflect the industry and education of a generation of young American women. They were an important aspect of early American decorative art history and provide a window through which to understand the changes in the educational institutions, the role of women, and the definitions of refinement and gentility that occurred in American society.

This article is dedicated to the memory of two old friends, Glee Krueger (1931–2018) and Betty Ring (1923–2014), who devoted themselves to researching early American schoolgirl needlework. We continue to appreciate their outstanding contributions to our knowledge.

1 For more on this topic, see J. M. Opal, Beyond the Farm: National Ambitions in Rural New England (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008); and Nancy F. Cott, Bonds of Womanhood: Woman’s Sphere in New England, 1780–1835 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1997). 2 Quoted in Lucia McMahon, Mere Equals: The Paradox of Educated Women in the Early American Republic (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2012), p. 70. 3 Niles’ Weekly Register, vol. 9 (December 2, 1815), p. 238. 4 Jacqueline Barbara Carr, “Marketing Gentility: Boston Businesswomen, 1780– 1830,” The New England Quarterly, vol. 82, no. 1 (March 2009), pp. 35–36. 5 Joseph Dennie, “Female Education,” Port Folio, vol. 4, ser. 3 (July 1810), p. 85. 6 Theodore Sizer et al., To Ornament Their Minds: Sarah Pierce’s Litchfield Female Academy, 1792–1833 (Litchfield, CT: Litchfield Historical Society, 1993), pp. 14–15. 7 Cott, Bonds of Womanhood, pp. 104–105. 8 John Bennett, Letters to a Young Lady (Newburyport, MA: John Mycall, 1792) pp. 148–149. The relationship of silk-on-silk embroideries to the emerging American Federal period style is discussed in such texts as Sumpter Priddy, American Fancy: Exuberance in the Arts 1790–1840, (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone Foundation, 2004). 9 Quoted in McMahon, Mere Equals, pp. 67–68. 10 Betty Ring, “Mrs. Saunders and Miss Beach’s Academy, Dorchester,” The Magazine ANTIQUES, vol. 110, no. 2 (August 1976), pp. 302–312. 11 Harriet Webster Marr, The Old New England Academies Founded Before 1826 (New York: Comet Press, 1959), p. 105. 12 Susan P. Schoelwer, Connecticut Needlework: Woman, Art and Family 1740–1840 (Hartford, CT: Connecticut Historical Society, 2010). Pictorial silk-on-silk embroideries were also produced in England at this time. Examination of the stitching and painting generally allows differentiation between American and English examples. 13 Samuel Folwell was first identified by Davida Tenenbaum Deutsch in “Samuel Folwell of Philadelphia: An artist for the needleworker,” The Magazine ANTIQUES, vol. 119, no. 2 (February 1981), pp. 420–423. 14 Quoted in Betty Ring, “Memorial embroideries by American schoolgirls,” ibid., vol. 100, no. 4 (October 1971), pp. 570–575. 15 Michael R. Payne and Suzanne Rudnick Payne, “Roses and Thorns: The Life of Susanna Paine,” Folk Art, vol. 30, no. 4 (Winter 2005/2006), pp. 62–71. 16 Quoted in Betty Ring, Girlhood Embroidery (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1993), vol. 1, p. 22. Many silk thread colors have faded with exposure to light for some two hundred years and it is sometimes startling to examine the more original coloration on the reverse of the embroidery. 17 Quoted ibid., vol. 2, p. 327. 18 Ibid., vol. 1, p. 212. 19 The Autobiography of John Trumbull, Patriot-Artist, 1756–1843, ed. Theodore Sizer (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1953), pp. 5, 82. 20 Glee Krueger, New England Samplers to 1840 (Sturbridge, MA: Old Sturbridge Village, 1978), p. 2.

MICHAEL R. PAYNE and SUZANNE RUDNICK PAYNE are collectors and members of the American Folk Art Society. This is the twenty-first article they have published about early American folk art.