The kimono is Japan’s signature garment. It’s timeless and simple—the word means “the thing to wear”—but it’s hardly static. Kimonos range from basic to elegant to wild. Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk, an exhibition organized by the Victoria and Albert Museum—highlights are viewable online at vam.ac.uk—explores the T-shaped robe’s storied past and modern sizzle.

The kimono is at least a thousand years old. Once plain, everyday dress, it got its fashion wings in the 1600s with the emergence of a bourgeois class craving luxury goods. Fashion was a force in Edo-period Japan, the time between 1615 and 1868. More than a fancy vacation home, more than jewelry, more than art on the wall, the kimono and its material and production values proclaimed sophistication and wealth. It became the personal billboard of choice and a vehicle for social competition.

Kyoto, the center of luxury textile production, was Japan’s fashion capital; the kimono, high fashion’s foundation. Everyone wore it. By the early eighteenth century, Tokyo was the world’s biggest city and the country’s business and cultural capital. There, people of all classes deployed the kimono to strut their stuff.

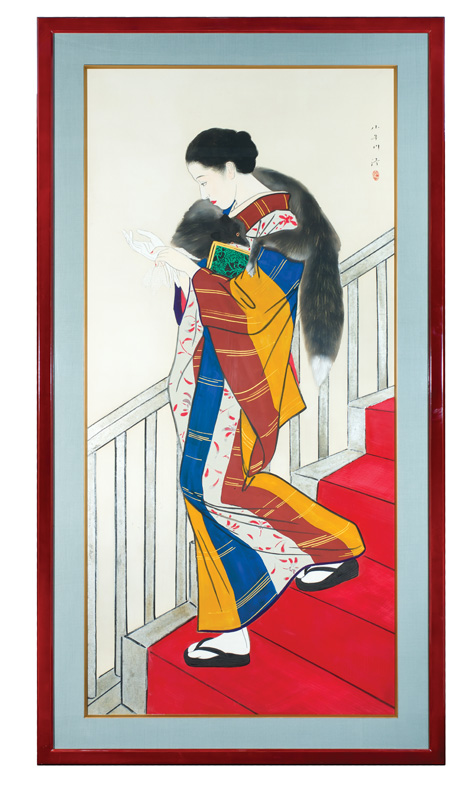

The kimono is best seen as a simple canvas, no flounces or furbelows allowed. It’s a straight-seamed garment secured with a waist sash. Unlike Western dress, which accentuates or disguises the body’s shape, the kimono’s flatness matters most. The body’s motion might highlight motifs but variations in the body’s shape rarely do.

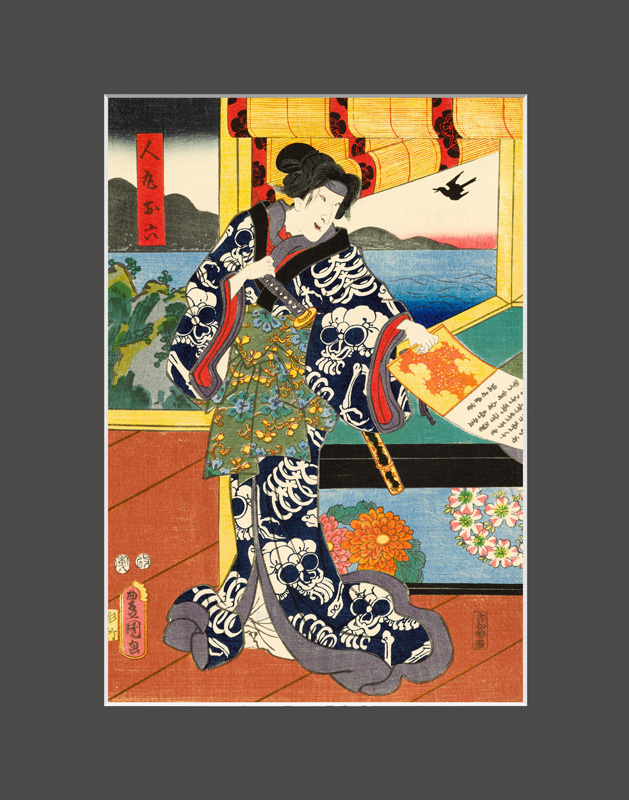

Designers and buyers splurged on exquisite embroidery depicting all kinds of imagery, and in riotous color. Tweaks in the basic form signaled status. Long, swinging sleeves meant the wearer was young and unmarried. Women from the samurai class had kimono designs created especially for them. Wedding kimonos then and now are major productions.

Historic kimono decoration could be abstract, figural, or calligraphic. Designs from the second half of the sixteenth century tended to place the dominant motifs on the right shoulder or the hem. Kimonos made between about 1800 and 1830 often featured single, undulating sweeps of color bordered by flowers and greenery. Satin weave silk kimonos and the finest silk embroidery made for a lustrous look. Passages of thread wrapped in gold or silver leaf added sparkle. Makers pushed chemistry to get exotic new colors. Kimonos for men were more restrained, but craftsmanship was no less exacting.

Japan opened itself to the world in the 1850s. Before long, a kimono export trade developed with design ideas batting back and forth from Europe to Japan. Japonisme was one of the nineteenth century’s central aesthetic movements, affecting fashion as well as art and architecture. Starting as a luxury lounging garment, the kimono eventually helped kill the corset. It’s the basis for the loose and layered look pioneered by Paul Poiret, Mariano Fortuny, and other couturiers early in the last century.

Closer to today, Thom Browne, Jean-Paul Gaultier, and Alexander McQueen gave the form a modern, dramatic twist, but perhaps the most famous kimono of all time clothed Obi-Wan Kenobi in seven Star Wars films. Call it a forceful fashion statement.