from The Magazine ANTIQUES, July/August 2016 |

With a boost from Broadway, the caretakers of Hamilton Grange cast new light on the charms of Alexander Hamilton’s once bucolic home.

The Broadway musical Hamilton has created something of a second American Revolution, reviving American promise in the person of a penniless bastard orphan who washed up on these shores and be came…Alexander Hamilton! It is this reprise of the old dream that has sent scores of people, most of them like me who know the show only from its cast recording, to Ron Chernow’s biography, exhibitions of Hamiltoniana at the New York Public Library, the Museum of the City of New York, and the New-York Historical Society, and on walking tours of Hamilton sites in lower Manhattan and Hamilton Heights.

The ten-dollar founding father without a father/ got a lot farther by working a lot harder/ by being a lot smarter/ by being a self-starter –Hamilton, Act I

Politically astute and historically savvy, the show casts African-American and Hispanic actors as the white Founding Fathers and gives those hoary figures enough hip-hop wit and wisdom to infuse Broadway with a bracing dose of democratic pride . . . at around $1,000 a ticket. Alexander Hamilton would have appreciated the contradiction.

Up in Harlem, Hamilton Grange is feeling the glow. Last year there were more than thirty-five thousand visitors. In the first six months of this year they have already equaled that number. They have a sweet story to tell in this house, the only one Hamilton ever owned, which was itself orphaned in the late nineteenth century as the street grid of the city marched north, with no place for a pretty yellow building that sat aslant of the new geometry. And so its porches were removed and it was taken from 143rd Street to Convent Avenue near 141st Street, where it was mashed up against the bulky Romanesque church of St. Luke’s and used as a rectory in one of the least felicitous pairings in a city known for them. It wasn’t until 1924 that the orphan acquired some stature as the former home of a certain Founding Father. After that the story gets better, culminating in 2008 when the National Park Service moved it across the way to Saint Nicholas Park, restored the porches, and gave it the charming rural aspect it had when the Hamiltons moved there with their seven children in 1802.

By 1802, two years before his early death, the most urban and urbane of our Founding Fathers was finally ready for his version of the pastoral. Adams had his fine New England farm, Jefferson and Washington their plantations, Madison and Monroe were similarly blessed. But the “founding father without a father” had no great liking for peace and quiet until sex and politics put him out of the game. “A disappointed politician you know is very apt to take refuge in a Garden,” he wrote, describing the project he and architect John McComb Jr. had designed on some thirty acres with fine views though no river frontage.

He called it the Grange in honor of the Scottish estate he liked to think of as part of his ancestry. It probably represented the only tangible emblem of his American success though the truth is he really couldn’t afford it. And surely there were people, his wife especially, who thought this rural envelope where he walked in the woods, read to his children, and often lay in the grass with them until sundown, would contain his increasingly reckless spirit. It didn’t, but that gets ahead of a story that belongs as much as anything to the people who have restored the Grange so beautifully.

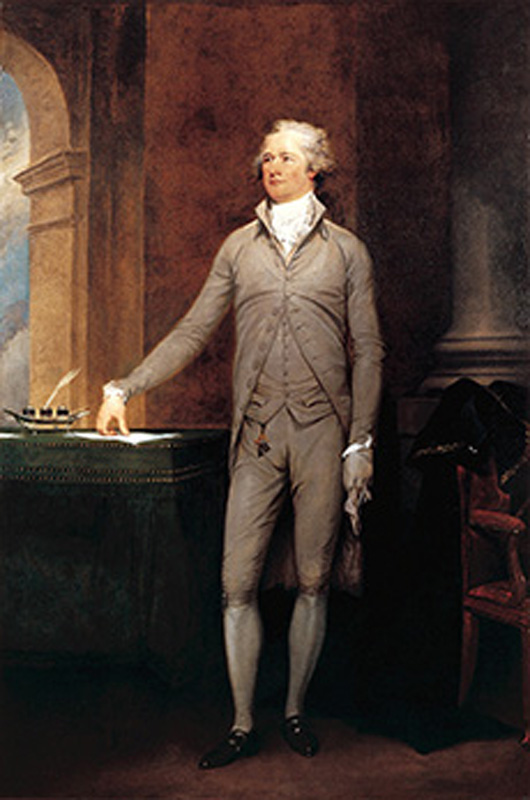

I went there first with Steve Laise who was chief of cultural resources for Manhattan sites during the National Park Service’s relocation and restoration of the Grange. The goal, he told me, was to create the impression of the family’s life in the two years between 1802 when they moved in and Hamilton’s death in 1804. They were both imaginative and rigorous in doing this. Thus the copy of the great John Trumbull portrait of 1792 that hangs in the hall would not have been there, but it was obtained to give visitors an immediate sense of Hamilton’s grace and his aesthetic. The entrance hall, Hamilton’s small office, and the beautiful octagonal parlor and matching dining room are the only rooms that have been interpreted, but they are probably the only rooms that mattered even back then. This is not an opulent house. It was well but not lavishly furnished and it was highly functional, designed, Laise tells me, to be operated by very few servants, possibly only one, though it is difficult to say, since the English basement where the washing and cooking took place was left behind when it was first moved.

It must be nice, it must be nice to have Washington on your side –Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr in Hamilton

Few of the furnishings are original, but most of them, like Hamilton’s desk, have been meticulously reproduced from originals in the Museum of the City of New York and elsewhere. Of these, Laise points with particular pride to the four-bottle silver wine cooler in the dining room. It is a copy of the one Washington gave the Hamiltons in 1797, soon after publication of the disastrous pamphlet in which Hamilton felt compelled to detail his affair with Maria Reynolds in order to clear his name of financial impropriety. Washington’s note to Alexander and Eliza pointedly says, “Mrs. Washington joins me” in expressing “every sentiment of the highest regard, I remain your sincere friend and affectionate and honorable servant.”The wine cooler stayed with Eliza until her death and was, Laise notes, a kind of life preserver for the Hamiltons.

The pianoforte tells another story. Though in need of restoration, it is the one that Angelica Church gave her niece Angelica Hamilton, who played it as her father sang. After the death of her beloved brother Philip in 1801 Angelica lost her mental bearings, and when the family moved to the Grange she continued to play the songs Philip had loved. Someone should finance its restoration so there is music in this house. It couldn’t have been so quiet here with seven children, frequent guests, and that antic fellow who eventually dug his own grave with talk.

I ended both my visits to the Grange in a kind of Hamilton euphoria, not so unusual I have since learned. Ron Bourgeault of Northeast Auctions, who might be expected to cross-examine every chair and epergne, tells me he arrived unannounced one day with two of his employees who had read about the Grange in connection with the Broadway show. He admired the reproductions, the two simple but spacious octagonal rooms, the dining room’s mirrored doors bringing the park inside, and the engaging video and interactive displays in the visitor center downstairs. Most of all, he and his companions were captivated by their guide, an African-American volunteer in his forties, a man from the neighborhood as it happens, who took them around with so much evident pride and enthusiasm. “Thank God it was moved,” Bourgeault says of the house. “Thank God for the play.” It’s like that up there.

Saint Nicholas is a ribbon park that runs downtown for several blocks from where it starts at the Grange. It has a surprisingly rural feel, rocky and grassy almost like the ridge where the Grange was originally sited. It’s peaceful, too, and easy to imagine when you listen to the part of Hamilton where Alexander sings of the quiet uptown as he and Eliza mourn young Philip’s death in a duel to defend his father’s honor. Guaranteed to bring out the handkerchiefs of everyone who hasn’t had their tear ducts surgically removed, this is the passage I thought of as I left the Grange the second time. I thought, too, of the careful man who had first taken me through the house, and of the volunteers and park rangers whose enthusiasm is so infectious. I give them my standing O.

In these comments, Steve Laise, the former National Park Service chief of cultural resources for Manhattan sites, guides us through the relocation, restoration, and furnishing of Hamilton Grange.

A “Sweet Project”

In 1799 Alexander Hamilton playfully wrote to his wife, Elizabeth, of his “sweet project,” which was to become the genteel home of his imagination. We also learned from his correspondence that, throughout his collaboration with noted architect John McComb Jr. and builder Ezra Weeks, Hamilton remained personally and passionately involved in the details of design and construction.

Hamilton’s thirty-two-acre property was typical of a “gentleman’s farm,” with a cowshed, springhouse, and other useful outbuildings. But the Grange could never have been mistaken for a simple farmhouse. Elevated front and rear entrances, ornamental balustrades, and a lovely triple-hung sash window, flanked by smaller windows with an alternating star-and-circle tracery, declare that this is a sophisticated design in the latest style.

In the absence of original plans or other detailed documentation, the restoration of the Grange as built depended largely on what the house itself could tell us. A painstaking examination conducted by the National Park Service revealed that a great many alterations had been made over time. But the eloquent voice of the remaining structure spoke clearly of Alexander Hamilton’s vision.

Steps Toward Preserving the Grange

The National Park Service project to relocate the Grange followed its rescue by St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in 1889, when it was moved to Convent Avenue, and the subsequent opening of the house as a historic site by the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society in 1924.

When the frame structure was first moved, the cellar and foundation were left behind, front and rear stairs and entrances were removed, and other alterations were made. Over time, the new site became crowded by buildings on both north and south sides, preventing the Grange from being experienced as intended.

Moreover, in settling the house on the new site, a lateral supporting cellar wall had apparently been omitted, eventually resulting in the instability of the floor in the center of the building. Other problems, including damage from water leaking through the roof, were discovered as we prepared the Grange to be moved a second time.

We realized that to move it the building needed to be lifted almost forty feet to clear the loggia of St. Luke’s. To secure the structure and prevent further damage, supports were placed throughout the interior, the chimneys were braced, and cables secured the house to the beams on which it was lifted. Nine dollies, each with its own propulsion and braking system, eased the Grange five hundred feet to St. Nicholas Park as we held our breath. In the end, the move went perfectly, no new damage had occurred, and we were ready to begin restoration.

Portrait of Alexander Hamilton

Inclusion of Trumbull’s magnificent likeness of Hamilton caused me more soulsearching than any other aspect of furnishing and decorating the Grange. Our goal throughout the restoration was to offer visitors an accurate impression of the home as Hamilton knew it, and there was no basis for assuming that Trumbull’s portrait would have hung there between 1802 and 1804. And yet…the easy grace and elegance of the figure speak to us of the refinement, achievements, and confidence of the man himself. We are not going to meet Alexander Hamilton as we enter his home, but when we view this portrait we recognize him as the author of the vision that guided the design of the Grange throughout. Here are the same sophistication, balance, attention to detail, and classic simplicity that we discover in the house. What better way to form an impression of the Grange as Hamilton intended it?

Our reproduction of Trumbull’s original was painted by Adrian S. Lamb (1901- 1988) and was a gift of the Partnership for New York City.

Elegance And Innovation

The Grange has several exciting architectural features. As originally sited, the elongated octagonal parlor and dining room were centered on the east-west axis, thus admitting maximum sunlight in both morning and afternoon. In addition, we discovered that the folding dining-room doors had been mirrored, so that when opened they reflected the exterior light. This feature has been reproduced and installed.

Enhanced lighting in the dining room was also provided by a mirrored silver plateau known to have been owned by Hamilton, which reflected the light of candles placed on the table and around the room. The room would also have held the four-bottle silver wine cooler that George Washington gave Hamilton in August 1797, a twin to one still found at Mount Vernon.

The selection of paint colors was based on samples of the earliest coat discovered through analysis of the many layers applied over the years. The Wilton carpets are of period design.

Furnishing the Grange

The Grange collection includes a few chairs, a pianoforte, and several other pieces known to have belonged to Alexander Hamilton, based on information in his cashbook and other sources. However, we had no way of really knowing what furniture had been in the Grange during his occupancy from 1802 to 1804. No inventory was taken at the time of his death. More critical was the fact that the family also rented homes in lower Manhattan, while Hamilton simultaneously maintained a law office downtown. Other museums generously allowed us to examine Hamilton-related items in their collections. We then located similar items “of the period,” found modern objects of traditional design, and had several accurate reproductions created.

We decided to furnish the parlor, dining room, study, and entry hall, reasoning that these were where Hamilton’s visitors would have been received or entertained, and so our visitors should experience them as well. In a way, we let the house itself tell us how it should be furnished. The delicate moldings, carved mantels, and other ornamentation reminded us that this was a showplace, to be furnished and decorated in the most stylish, yet graceful, manner available to Hamilton.

Notable Reproductions

The Museum of the City of New York generously allowed the cabinetry firm Fallon & Wilkinson of Baltic, Connecticut, to examine every detail of the Hamilton desk in its collection. Our resulting reproduction, used in the study to represent his “Secretary in the country,” is correct in every detail. Fallon & Wilkinson has also reproduced chairs from those in the Grange collection, as well as other items similar to those thought to have furnished the house.

As with the pianoforte that belonged to Angelica Hamilton, those objects that would have had the greatest meaning to the Hamiltons were chosen to be the basis for our presentation. These included the silver four-bottle wine cooler Washington gave the Hamiltons, which was sold out of the family in 2012. We felt that this thoughtful gift, coming just a month after the embarrassing revelation of the Maria Reynolds affair, must have been of huge personal significance to both Alexander and Elizabeth. We therefore requested permission to have a reproduction produced, and are delighted with the resulting masterwork by MJF Silversmiths of Williamsburg, Virginia, now in the dining room.

Photograph by Kevin Daley, National Park Service.