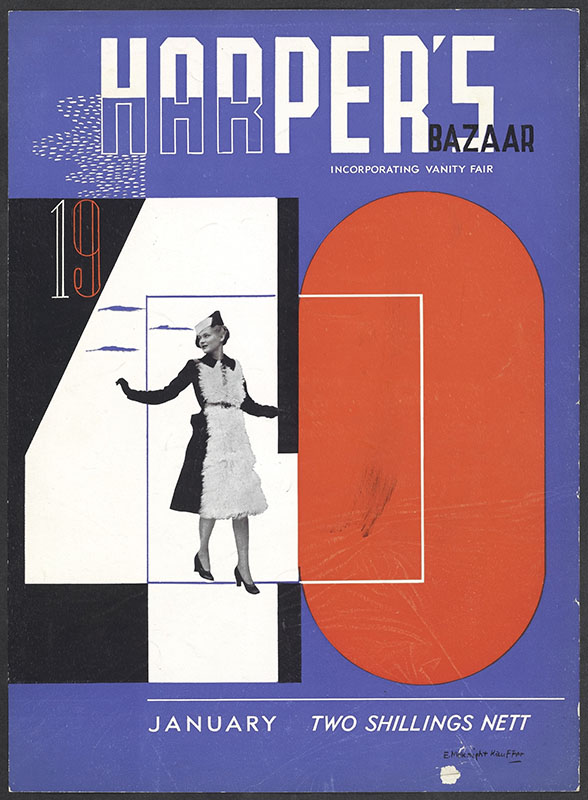

For nearly twenty years between the two World Wars, E. McKnight Kauffer, an American, was the most celebrated graphic designer in England (Fig. 8). He was best known for his eye-catching posters, but his book covers and illustrations, graphic identities, carpets, stage sets, costumes, and ephemera were also among the most arresting of his era. Kauffer’s distinctive artistic perspective quickly gave rise to such an outstanding reputation that, by the early 1920s, one of his clients could placate a waiting public between designs by papering billboards with a label: “A New McKnight Kauffer Poster Will Appear Here Shortly.”

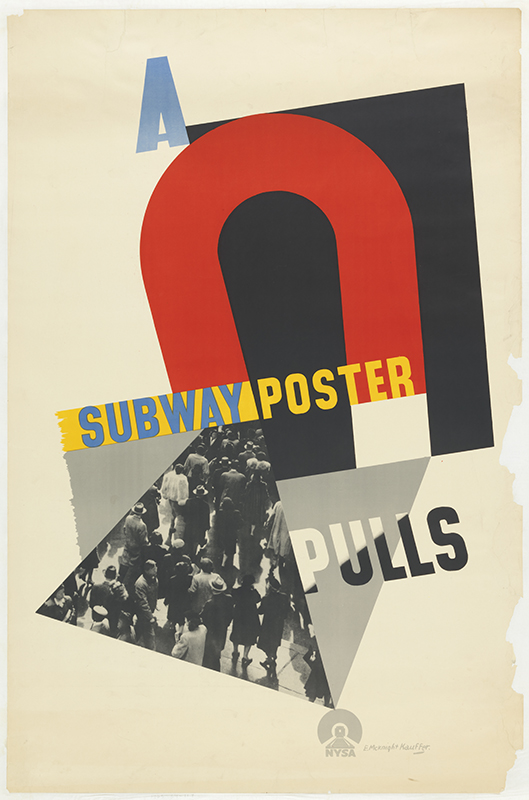

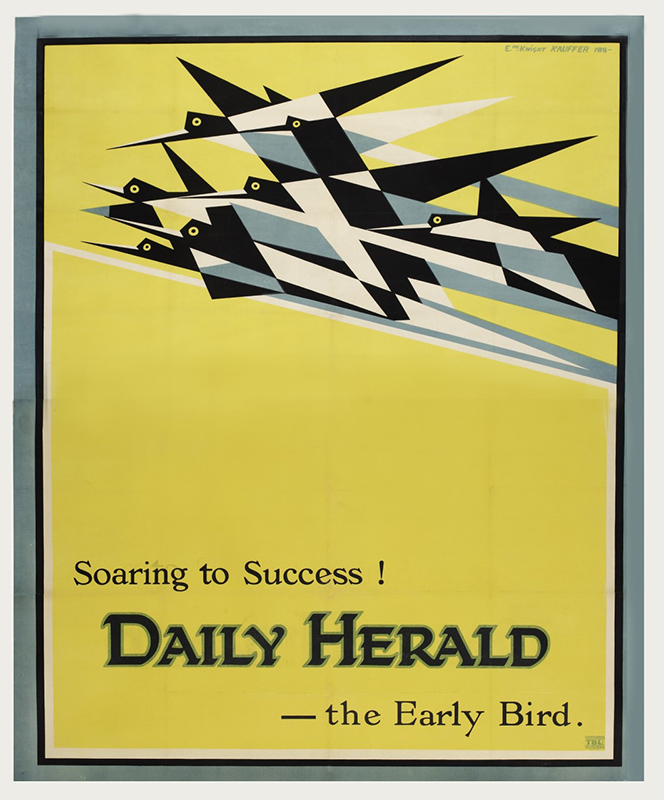

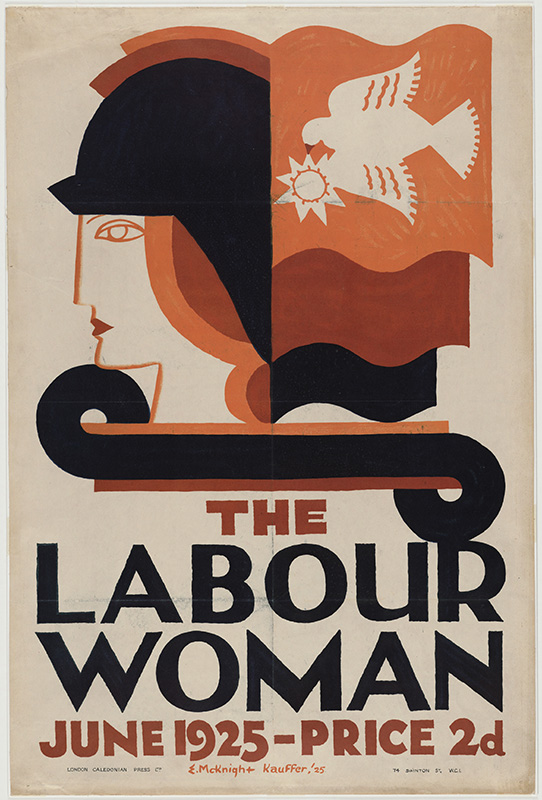

A man of populist conviction, Kauffer believed fervently that modern art should move beyond the walls of museums and galleries to infiltrate all elements of daily life. His belief that innovative expression should be matched by social and cultural engagement marked him as a modernist. From the outset of his career until his death, Kauffer championed the principle that a designer held a responsibility not only to his client but also to his public. A poster, he believed, was a work of art that served the dual purpose of informing people and aiding industry. It was an opportunity both to share important information and to introduce people to a new way of seeing. Kauffer’s genius lay in his ability to synthesize conventions of the avant-garde and to adapt them to the needs of a client and to respond to the public’s desire to be challenged. Although “E. McKnight Kauffer” was for a time a household name, it was not synonymous with one style, but evocative of many. Kauffer constantly sought to metabolize what he saw in contemporary visual culture and make it relevant and new to an awaiting audience.

Fig. 4. Winter Sales Are Best Reached by the Underground, designed by Kauffer, 1921, published by Underground Electric Railways of London Company, printed by Vincent Brooks, Day, and Son, London. Lithograph, 39 5/8 by 24 5/8 inches. Collection of Merrill C. Berman; photograph © Merrill C. Berman Collection.

In art and life, Kauffer was “as a bird, forever in flight, forever searching for a place to come to rest.” Born in Great Falls, Montana, in 1890, he was restless from an early age. He spent his childhood in Evansville, Indiana, leaving school before the age of fourteen to paint scenery for the town’s Grand Opera House. While still a teenager, he left home for good. He joined a traveling theater company as a scene painter, then found work in California, first on a fruit ranch and later at Paul Elder and Company, an influential bookshop in San Francisco. Over a period of just two years, Kauffer passed through Chicago and Baltimore in the United States, Algiers in North Africa, Naples, Venice, Munich, and Paris on the Continent, and Durham in the northeast of England before establishing himself in London by early 1915. As he experimented stylistically during this period, Kauffer also tried out a variety of monikers: Edward Kauffer, Edward Leland Kauffer, Edward McKnight, Edward Kauffer McKnight, Edward McKnight Kauffer, and finally E. McKnight Kauffer. But to his friends, he went by Ted.

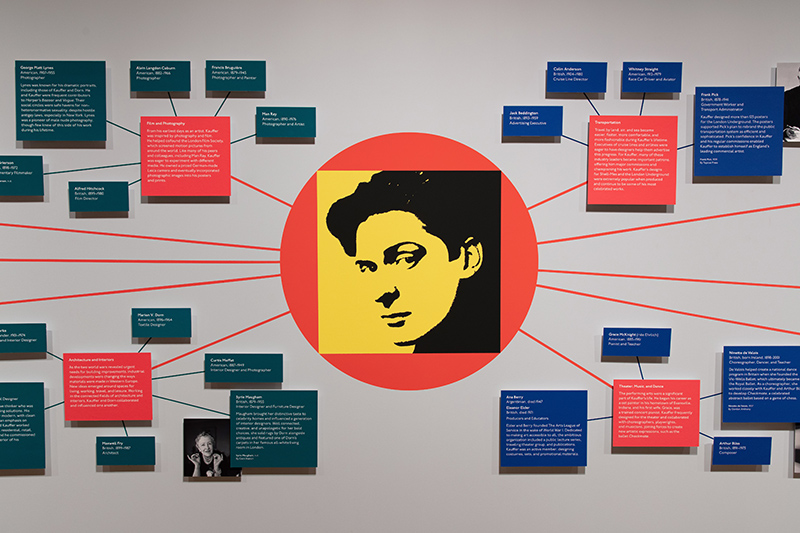

Personal relationships were the crux of Kauffer’s creative life. He was handsome and charming, described by arts patron Sir Colin Anderson as “like a slim, russet eagle in appearance . . . cultured, intelligent and hypersensitive.” A voracious reader and consumer of culture, Kauffer formed close friendships with writers, critics, and artists. Arnold Bennett, Sir Kenneth Clark, T. S. Eliot, Mary Hutchinson, Aldous Huxley, Marianne Moore, S. J. Perelman, and Virginia and Leonard Woolf were just some of the members of his circle. As his star rose, Kauffer always worked to elevate others, helping artists including Man Ray and Zero (Hans Schleger) to establish themselves in London, and drawing William Faulkner to the attention of Alfred and Blanche Knopf.

Kauffer grew professionally alongside his romantic partner and later wife, the American textile designer Marion Dorn (Fig. 9). They collaborated on rugs and interior design projects and shared clients, including the Fortnum and Mason department store and Orient Line cruises. Dorn achieved many independent design successes during her years in London, but Kauffer’s fame at times overshadowed hers. She once wrote to Hutchinson, with whom she was very close, “I had a terrible week . . . with those parties at Claridges and since I have had a little publicity, I am called in brackets—wife of E. Mack. Kauffer—in today’s Observer. Because obviously no woman must ever be said to do anything on her own. I expected it but it made Ted wild.”

The end of the Great War brought a new emphasis on the value of art as a support for industry. A new and distinct role emerged, that of the modern designer, a development to which Kauffer contributed substantially in the London of the 1920s and ’30s. In its inaugural issue of October 1922, the journal Commercial Art promoted art’s use in commerce as “constant, immense and indispensable” and called upon both artists and progressive businessmen “to show the way and make the sacrifice of giving a good example.” Kauffer championed the belief that the promotion of anything from dry cleaning to an antacid was an occasion for graphic innovation, but he also insisted that a designer “must remain an artist. He must be more interested in [commercial] art as an art than as a business.” And he was indeed more artist than businessman —his artistic integrity and perfectionism often came at the expense of his financial stability, somewhat ironically given his commitment to a sector that aimed at a productive combination of the two. While maintaining his distinctive point of view, however, Kauffer believed firmly that direct engagement with clients was essential to his profession, “an absolute necessity in obtaining good results.”

Fig. 8. Photograph of Kauffer by Maud B. Davis, c. 1920. Gelatin silver print, 8 by 6 inches. Collection of Simon Rendall; photograph by Hugh Gilbert.

Fig. 9. Marion Dorn (1899–1964) in a photograph by Carl Van Vechten (1880–1964), 1936. Photographic print, 9 7/8 by 7 3/8 inches. Collection of Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale Collection of American Literature; photograph © Van Vechten Trust.

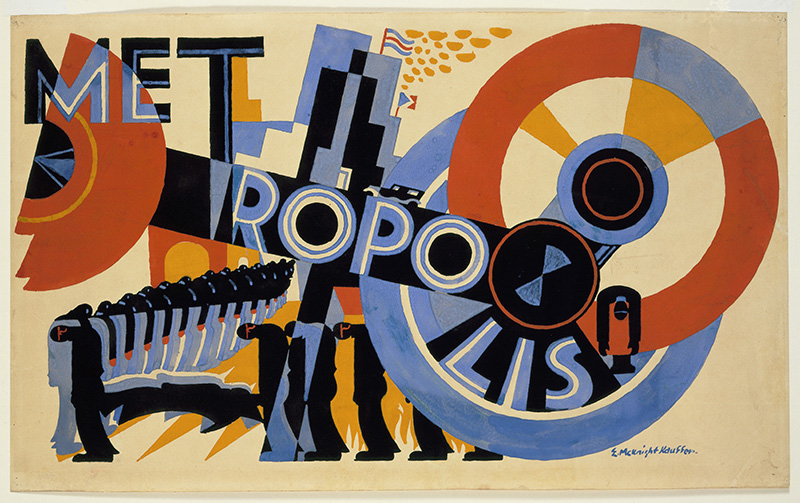

Not everyone was convinced, however, of the value that Kauffer’s sophisticated style could bring: in 1926 the film company Gainsborough Pictures rejected several of his poster designs. Kauffer was at the height of his celebrity at the time, and the slight made headlines: “Posters Too Good for the Films,” the papers reported. Both works had been designed to promote Alfred Hitchcock’s thriller The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog. “They are sort of Futurist and quite attractive,” a Gainsborough executive is quoted as saying, “but for one thing we did not want the public to think the film was one of these expressionist pictures like ‘Dr. Caligari.’” Despite the rejection of his posters, Kauffer remained involved in the project, ultimately designing the film’s titles. Another film poster Kauffer designed, Metropolis, was also never produced (Fig. 15).

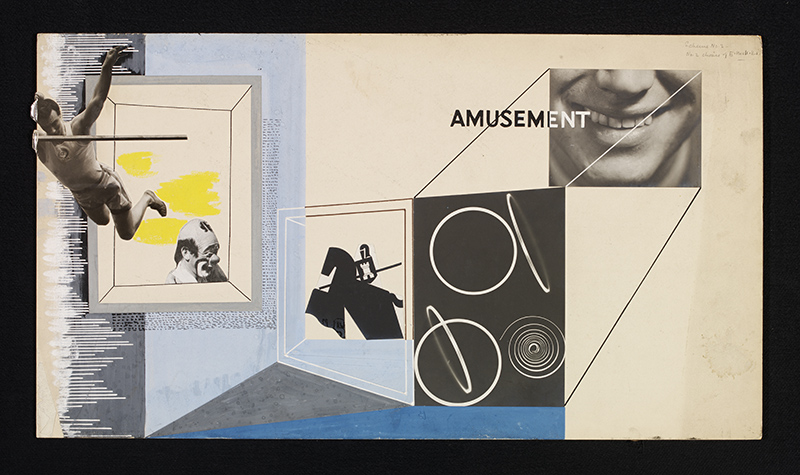

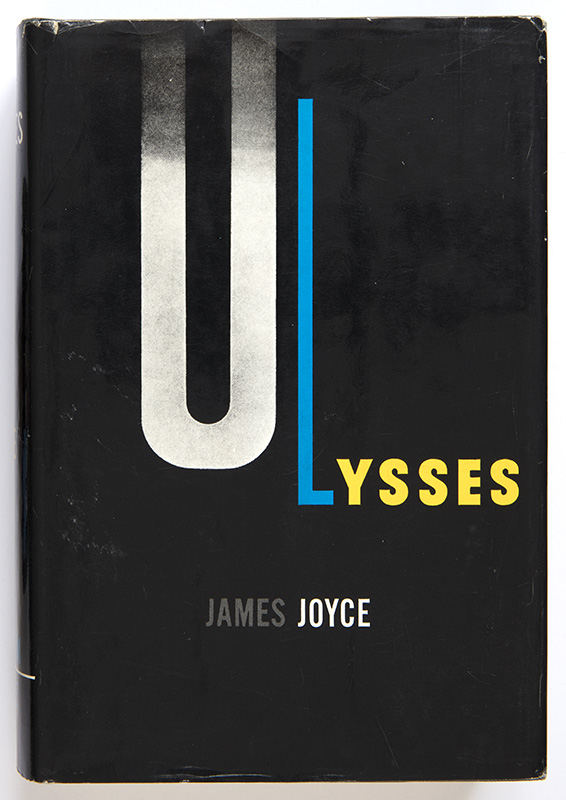

Meanwhile Kauffer was finding an increasingly large market for his book jackets and illustrations. Many publishers sought out his aesthetic to captivate new audiences, and by the mid-1920s literary design made up a significant part of his practice. This steady work continued for the rest of his career. Kauffer regularly collaborated with the Hogarth Press, founded in 1917 by the Woolfs; Nonesuch Press, founded in 1922 by his friend Sir Francis Meynell; and the reinvigorated Curwen Press. Each published affordable and finely produced editions of fiction and poetry, by authors including Bennett and Eliot. Kauffer also worked regularly for larger publishers, including Chatto and Windus, Victor Gollancz, Doubleday, Doran, Random House, and Alfred A. Knopf.

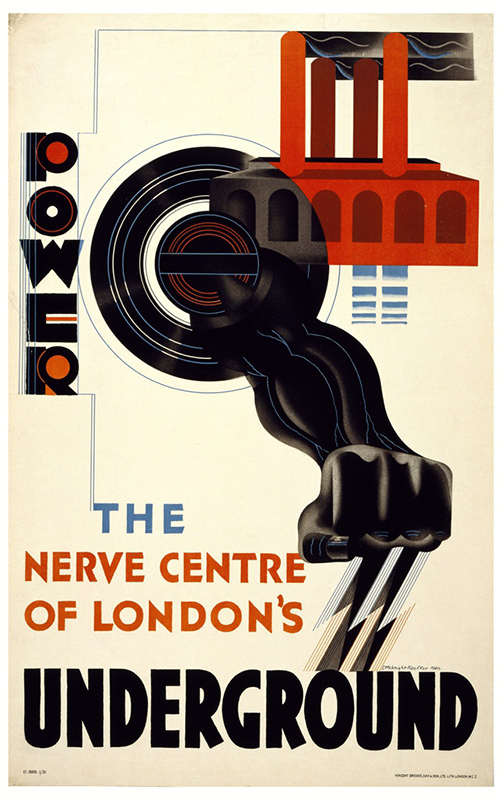

Driven both by the reputation of his talents and the nature of his personality, Kauffer forged client relationships with those who shared his ideals. One formative example deserves recognition here. In Frank Pick, a top manager of the London Underground transit system and founding member, in 1915, of the Design and Industries Association, Kauffer discovered a like-minded individual dedicated to raising the creative potential and public appreciation of design through the company’s station architecture and posters (Fig. 1). It was in large part through these posters for the Underground that Kauffer was able to develop his own stature, whether he was promoting an open-air destination with a pastoral landscape or encouraging museum attendance with a cubist composition.

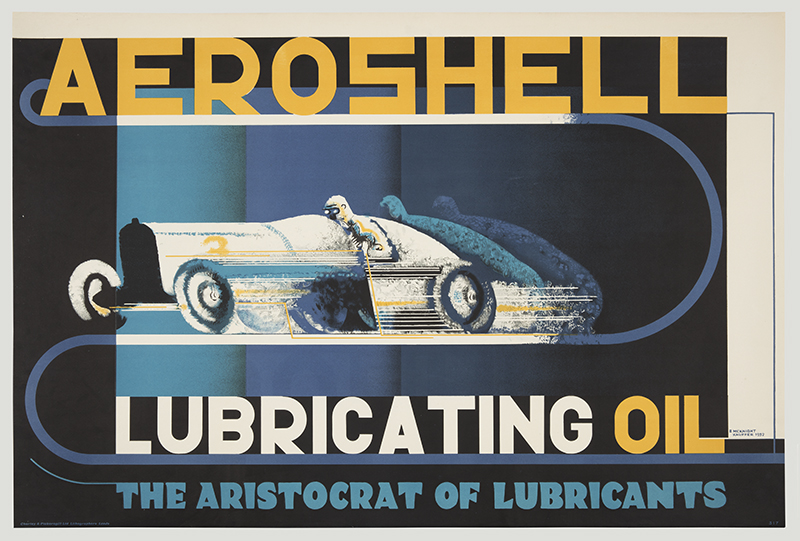

In the early years of his career, Kauffer produced some designs for the oil company Shell-Mex and B. P. (Fig. 7). With the arrival of Jack Beddington, the company’s forward-thinking publicity manager, in 1928, that relationship flourished into one of his most significant collaborations. In exhibitions in London in the 1930s, Beddington presented the company’s advertisements, guidebooks, and posters in the context of fine art. Sir Kenneth Clark, director of the National Gallery and a close friend of Kauffer’s, wrote the introduction to the catalogue for Exhibition of Pictures in Advertising by Shell-Mex and B. P. Ltd., at Shell-Mex House, calling the company “among the best patrons of modern art” for the last seven or eight years. In New York in the 1940s, advertising executive Bernard Waldman tenaciously championed Kauffer’s talent, helping him to secure numerous commissions. Among the most significant was the American Airlines campaign, for which Kauffer produced more than thirty posters (Fig. 5). Waldman, his wife, Marcella, and his daughter, Grace, became Kauffer’s adoptive family.

The volume of Kauffer’s poster output, as well as the frequent changeover of posters in London’s transport system, meant that the city’s hurrying commuters and pedestrians experienced his images repeatedly in their daily lives. As a contemporary critic observed, Kauffer eagerly responded to the quickening pace of contemporary life, designing posters for the “fastmoving” public and aiming to “express the message in the simplest and most direct form.” He evoked a different form of swift communication, among the fastest known at the time, in describing the poster as “not unlike a terse telegram that gets to the point quickly.” The emergence of new and efficient ways of communicating and traveling in the first half of the twentieth century provided Kauffer both with abundant new clients and with subjects for posters—from air mail and telephones to ocean liners and trains.

In fact, fleeting opportunities for experiencing Kauffer’s dynamic designs could be found in myriad aspects of contemporary leisure: his set and costume designs for ballets and the theater appeared on stages around the world (Figs. 14, 17), his display designs attracted attention in exhibition halls and shop windows, his clever greeting cards filled mailboxes, and his striking packaging sold laundry detergent and textiles. For those clients ready to depart from tradition at home, Kauffer’s designs modernized domestic spaces; his book jackets lined the shelves of private libraries, his murals and tapestries brought pattern and color to interior walls, and his and Dorn’s carpets lined the floors of some of London’s first modern apartment buildings. The multiplicity of Kauffer’s output, breaking down creative boundaries, contributed to his status as a modern designer. As Francis Meynell reflected, “Kauffer was an example of the abandoned truth that art is indivisible: that a man with the root of the matter in him can paint or design rugs (as he did for Arnold Bennett) or make posters or illustrate books or decorate a room or parti-colour a motor-car (as he did for me) or scheme an advertisement.” Intersecting with the fields of architecture, interior design, literature, publishing, the performing arts, and retail, Kauffer and Dorn’s projects brought them into a network with some of the most prominent proponents of English modernism—figures including composer Arthur Bliss, architect/ designers Serge Chermayeff and Wells Coates, architect and artist Frederick Etchells, fashion journalist Madge Garland, artist and interior designer Curtis Moffat, playwright George Bernard Shaw, and choreographer Ninette de Valois.

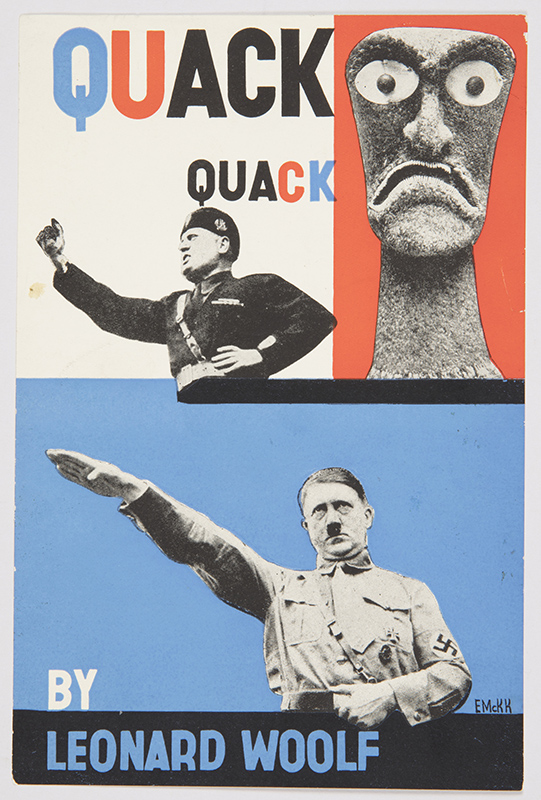

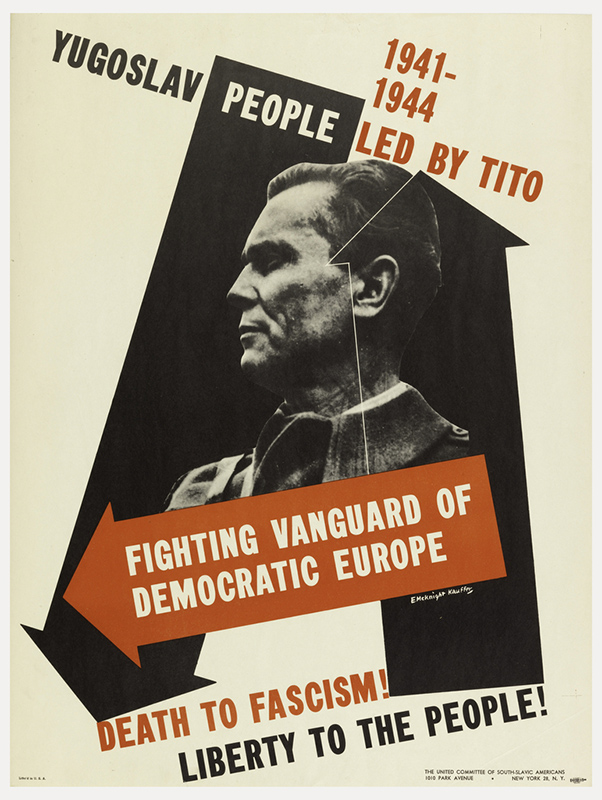

Kauffer was in many respects an activist, advocating for the importance of design in the service of the public good. In 1919, in the wake of World War I, he was a founding member of the Arts League of Service, an organization aimed at increasing access to art and culture through exhibitions on modern art, literature, dance, and music, as well as a traveling theater troupe that ventured throughout Britain. He continued to design for the ALS during the 1920s. Kauffer was known as progressive and socially liberal but was not especially engaged in politics in the 1920s and early ’30s. Despite this reputation, Kauffer participated in several harmful and insensitive commissions during this period. His ultimately unpublished illustrations for a special edition of Carl Van Vechten’s 1926 novel set in Harlem, whose title includes a racial slur, demonstrate that Kauffer was at best na ve about matters of race. His illustrations for the Earl of Birkenhead’s 1930 book The World in 2030 A.D. anchor a text that is imbued with misogyny and supportive of eugenics. His symbolic cover design for the 1932 fascist treatise The Greater Britain by Oswald Mosley seems to stand in contradiction to Kauffer’s stated beliefs, yet his active participation cannot be overlooked. But as political upheaval escalated in the 1930s, he became earnestly engaged with a range of worthy causes, lending his talents to organizations including the Peace Poster Service, the Association of Writers for Intellectual Liberty, the Union of Democratic Control, and others. Kauffer’s disdain for fascism is potently revealed in his powerful cover for Leonard Woolf’s 1935 critique of European dictatorships, Quack, Quack! (Fig. 12).

After the outbreak of World War II, Kauffer and Dorn moved to New York. Once there, Kauffer continued to support a sophisticated cultural response to wartime needs, working on commissions from the American Red Cross, the Greek War Relief Association, the National War Fund, and more. In 1947, to honor his war-relief efforts, he was named an honorary advisor to the United Nations’ Department of Public Information, and he designed a poster for the newly formed organization.

“I had never felt quite at home in my own country,” Kauffer once recalled, yet throughout his time abroad he had remained an American citizen. The restlessness that carried him across the United States and then to Europe in 1913 never truly abated. He had arrived in England as a refugee, fleeing Paris with his first wife, Grace McKnight Kauffer (n e Ehrlich), at the outbreak of World War I, but would recall, “I think even then, I had the idea in the back of my mind that someday I would go back and find my place.” He did indeed return briefly to the United States in 1921 hoping to establish himself there, but found limited opportunities and soon returned to England. A 1925 notice in the London newspaper the Daily Chronicle suggested that Kauffer intended to become a British citizen, but he never did. Instead, he remained an expatriate for twenty-five years. When World War II made his status as an American untenable in England, he left abruptly for New York and never returned.

Although Kauffer prized individual relationships above all, he struggled with the people he loved most. In 1923 he abandoned Grace and their young daughter, Ann, having fallen in love with Dorn. The decision to leave his daughter haunted him for the rest of his life. He and Dorn had a happy relationship for many years, championing each other’s work. In London and later in New York, they kept company with a tight-knit circle of peers who fed each other socially, creatively, and, at times, romantically. Despite their fame and professional success, Kauffer and Dorn weathered years of financial precariousness and bouts of emotional turmoil that led to several periods of separation. The challenges of their return to the United States ultimately proved too much for their relationship, and although they married in 1950, they were largely estranged in the final years of Kauffer’s life.

In many respects, Kauffer remained an expatriate on both sides of the Atlantic: an American designer in Britain, a British designer in America. Although this lack of belonging took its toll on those he loved, it was his stubborn resistance to settling that was the wellspring of his talent. He was always seeking something new, and he thrived when given the opportunity to use his creative abilities for the betterment of all. His firm belief that design was a responsibility distinguished him, for he held equal respect for the advertiser and the public. He took to heart the privilege of communication with all people in the fleeting moments of their lives. Kauffer was a modern designer for modern life.

This article is excerpted and adapted from E. McKnight Kauffer: The Artist in Advertising, the publication accompanying the exhibition Underground Modernist: E. McKnight Kauffer, on view at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, in New York to April 10. All notes and sources can be found in the catalogue, edited by Caitlin Condell and Emily M. Orr and published by Rizzoli Electa.

CAITLIN CONDELL is associate curator and head of drawings, prints and graphic design at Cooper Hewitt. EMILY M. ORR is assistant curator of modern and contemporary American design at Cooper Hewitt.