“Singularly gifted.” “Superb promise.” “Still young.” “Modern art in his death has had a heavy loss.” Those excerpts come from a poignant unsigned essay in the New York Herald of February 5, 1922, and commemorate an artist largely lost to history: Swiss-born Paul Thévenaz, dead at the age of thirty, victim of a burst appendix while a houseguest on a thunderstorming weekend in Rye, New York. He was not only talented, but handsome, sociable, and adored. “Everyone is sad and full of bitterness about that beautiful life being snuffed out,” John Wanamaker staff decorator Ruby Ross Goodnow (later Wood, 1880–1950), a commissioner of multiple works from Thévenaz, wrote in her diary, which remains in private hands. “I went to bed early and cried myself to sleep. I wonder if anyone was ever more beloved than Paulet?”

Educated in Geneva as a dancer and artist, Thévenaz lived briefly in Italy before heading to France, where he had an intense affair with Jean Cocteau, who was shattered by its abrupt end. By 1917 he was in America, having already established himself well enough in Manhattan to warrant a profile in Vanity Fair, where he was described as a “Rhythmatist,” which was apt since he had also been rigorously trained in what came to be known as the Dalcroze method of eurhythmics.1 Swiftly, Thévenaz gained a following as a portrait artist, an allegorical painter, a muralist, and a dancer, befriending forces in interior design and the decorative arts such as Goodnow and Elsie de Wolfe and attracting a society clientele. Heiresses Alice DeLamar (1895–1983) and Florence Blumenthal (1875–1930) were his champions, the former a philanthropic lesbian and Thévenaz intimate, the latter the soignée first wife of George Blumenthal (1858–1941), a president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. For them, Thévenaz completed two of his most highly regarded wall mural projects. One was populated with images of contemporary film stars for DeLamar’s private motion-picture screening room at her estate in Glen Cove, New York.2 The other was for the subterranean swimming pool in Blumenthal’s Fifth Avenue mansion, which he transformed into an undersea garden of fish, flowers, shells, seaweed, and mermaids, its centerpiece being a nude woman (seemingly Mrs. Blumenthal, if the facial features can be trusted) floating amid the marine life like an aquatic belle dame sans merci. Who knows what Thévenaz could have accomplished if he had had more time? One of his lovers, poet Witter Bynner (1881–1968), compared him to the British poet Rupert Brooke (1887–1915), similarly extinguished too soon, hailing him as “a sunlit youth . . .eclipsed among artists.”3

The majority of Thévenaz’s works seem to have been lost or have faded into obscurity, some the victims of demolition (DeLamar’s screening room and the Blumenthal pool area, among them). One notable survivor, though, can be seen as close to its full glory as possible: a ceiling mural executed for the Casino at Vizcaya Museum and Gardens in Miami, Florida, newly restored to its full technicolor glory after years of battering from the elements, a near-disastrous roof leak, and some quite peculiar (if possibly well-intentioned) interventions. Reaching the Casino takes a certain commitment, it must be admitted. One drives through a surprisingly narrow gateway past a thicket of tropical overgrowth to the magnificent house museum at the edge of Biscayne Bay, traverses the gardens, and climbs a steep and dramatic flight of stairs to be transported to another world within an already unworldly place.

In the context of today’s bustling, over-urbanized, and skyscrapered Miami, the operatic villa and its vast formal and fantastical gardens almost seem to emerge from a dream: glistening and decaying all at once, almost as if they were an illusion not reality, a testimony to wealth, vision, artistic talent, and connoisseurship, though not necessarily in that order. In the words of former conservator Lauren Hall, Vizcaya is “one of the most magical of houses,” but it is also at risk—troubled by the rising waters of Biscayne Bay, threatened by hurricanes, and beholden to the heat and humidity of a subtropical climate. It is a curator’s dream and a conservator’s nightmare. “It is,” says Kelly Ciociola, a previous conservator and a long- time consultant, “in a particularly precarious position.”

Vizcaya was conceived as the winter home of the world-traveling Chicago industrialist and heir to the International Harvester fortune, James Deering (1859–1925), who created it in association with his friend and advisor, artist and interior decorator Paul Chalfin (1874–1959). Described in Goodnow’s diary by architect Philip Trammell Shutze as “the finest painter ever turned out by the Accademia Roma,” Chalfin worked on the design, construction, and furnishing of the house and in general oversaw the entire 130-acre project, which lasted from 1914 to 1921. (The property today has been much reduced.) Architect F. Burrall Hoffman (1882–1980) designed the house and many of the accessory buildings. Diego Suarez (1888–1974), of Colombian and Italian descent and Italian training, oversaw the gardens. Another architect, Phineas Paist (1873–1937) of Philadelphia, was hired by Chalfin in 1916 and either designed or refined many of the yet-to-be-finished buildings. Vizcaya’s architectural roots are Italian, but like so many historic buildings in Florida, it is part old, part new, part borrowed, and part invented. The late architectural historian Carolyn Pitts accurately and amusingly identified it as “a mélange of Baroque, Rococo, Mannerist, and Louis XIV, adapted to a beach house in South Florida” in the National Historic Landmark nomination form for the estate.

Despite an appalling ego, Chalfin was talented, and beyond all else, an amazing shopper. Even before Vizcaya was a concept or Deering a client, he had been accumulating furniture, art, decorative objects, fragments—ornamental, decorative, artistic—with no immediate purpose in mind, and, as was the wont of the times, pieces of rooms to use in the palatial mansions being erected by America’s very rich. He also ultimately took credit for almost everything at Vizcaya. By the 1950s, both Hoffman and Suarez, each of whom had left the project before it was completed, began to reclaim the narrative, and, on Hoffman’s part, filing a lawsuit. Paist, on the other hand, remained with Chalfin long enough to see the unfinished architectural projects to completion, among them the Casino.

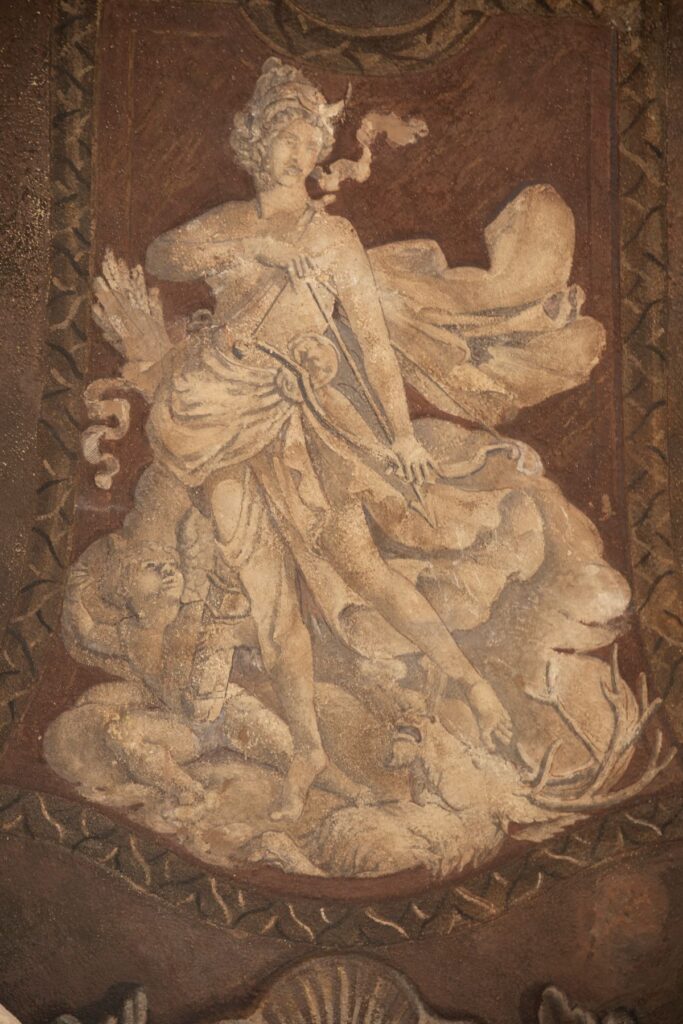

Chalfin had already brought in other contemporary artists to work at Vizcaya: sculptor Alexander Stirling Calder (1870–1945), whose works adorn the breakwater in the form of a giant stone boat; muralist Robert Chanler (1872–1930), who painted the pool area; and the decorative ironwork artist Samuel Yellin (1884–1940), who left his mark all over the house and its grounds. Then there was Thévenaz. The Swiss youth had met both Chalfin and Deering in Europe earlier and, being openly gay, as was Chalfin, he ran in the same social circles. In 1920, just as his career was blossoming, Thévenaz was asked to take on a challenging project at Vizcaya: to complete a ceiling in the Casino, a building that marks the southern end of the garden, atop a mound that Suarez created to deflect the glare from the lagoon behind it. From a distance, the Casino, inspired by a similar garden structure at Italy’s Villa Farnese, seems almost mirage-like, “a folly that is also functional,” according to Ciociola. Even up close, it reveals itself slowly and remarkably as it rises above the landscape, a structure fashioned of oolitic limestone, coral rock, and stucco painted in a lime-based paint intended to impart an instant sense of antiquity. The center of the structure is an open-air loggia set atop man-made grottoes; the two single-story wings on either side are actually two stories, the lower level being below grade.

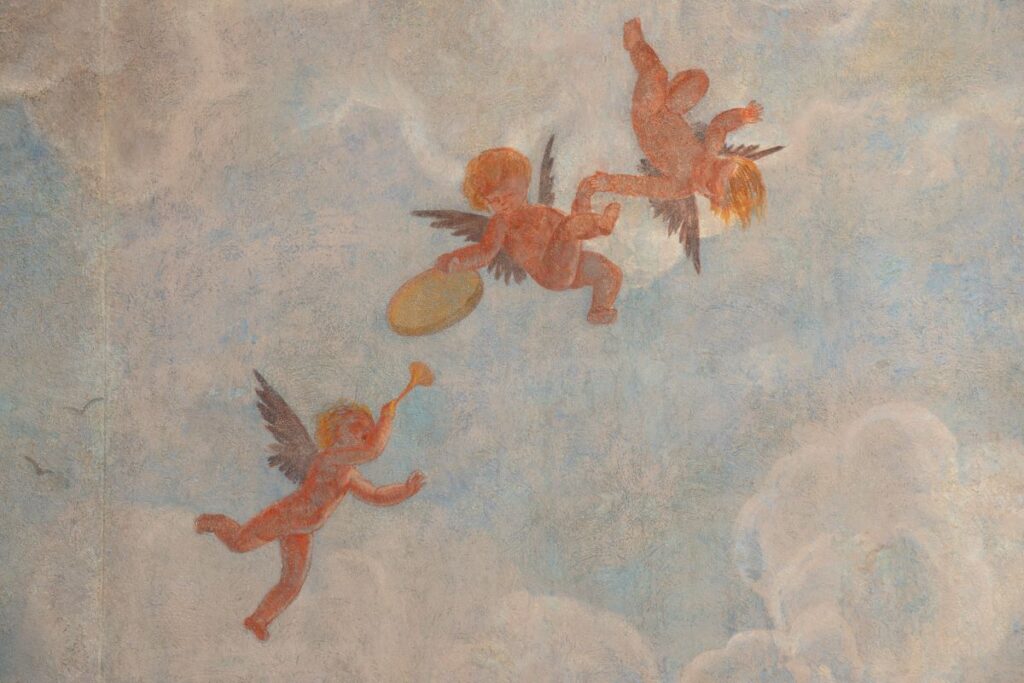

In 1914 Chalfin had purchased ten painted panels that had been produced in the studio of the rococo artist Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770), arguably the greatest painter of the eighteenth century. The panels were not the work of the master but rather in his style, works with a kinship to the 1761–1762 ballroom ceiling at Villa Pisani in the Veneto, entitled The Apotheosis of the Pisani Family, and a 1752 oil sketch called Allegory of the Planets and the Continents, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The latter was created as a proposal for the decoration of a staircase ceiling for the palace of Carl Philipp von Greiffenklau, prince-bishop of Würzburg. A fragment of an early letter from Thévenaz to Chalfin in the Vizcaya archives offers evidence of the challenges he faced in creating an exuberant central scene to be surrounded by the Tiepolesque panels. “Just before going any further,” he wrote, “I must tell you that the preparation of the canvas does not seem to be as solid as I thought. I may be mistaken about it, and I trust that no cracks will appear but I thought I had better tell you that, of course, I cannot take any responsibility [in] regards to possible troubles.” But the project was also the perfect opportunity for Thévenaz to pursue his interest in allegory, since the panels included six pudgy putti, along with Poseidon and Aphrodite and an array of classical ornament. Thévenaz, in turn, filled in the center with celebratory Renaissance figures and what Gina Wouters, a former Vizcaya curator, terms an “endless trompe l’oeil sky” hosting little cherubim.

The mural has endured multiple indignities since Thévenaz completed his work. Some years back, a roof leak forced Vizcaya’s conservators to remove two panels; the wood armature that held them in place was failing. One discovery led to another, and for a period a printed reproduction replaced the most damaged panels. For ArtCare Conservation—founded in New York but with offices in Miami and Los Angeles—the most recent restoration challenge was not merely technical and artistic but also required a certain amount of deduction. As ArtCare paintings conservator Lindsey Morris points out, “You could see where the Tiepolos were spliced together. There were elements that didn’t fit with the same style.” She and her fellow experts found evidence that Thévenaz had made some additions, among them a bouquet of flowers held by one putto. Other, later interventions, were not as welcome. A repainting in the 1980s—by whom and precisely when seems to be undocumented—gave the chubby little putti rippling pectorals and more masculine facial features. Those additions were creatively resolved by ArtCare’s Dafne Ozuna, an artist as well as a conservator, who positioned her young nephew (“very chunky” at the time, she said) in the poses of the putti to help her regain their softness.

“Our approach to treatment was to honor the original,” Sarah Linder of ArtCare says. “There was a lot of love put into it, but it was also a little scary.” Restoration at this scale involves forensics to find what Lindner calls “the elemental essence.” The team was able to identify the original material in the painting—the Tiepolo studio’s palette reflected that of the old masters, while Thévenaz used more Renaissance-based colors, mostly blue. ArtCare also spotted a nod to the era in which Thévenaz’s mural was painted: the bobbed hair seen on the female figures. “We approached [the restoration] with respect and reverence,” Morris explains. “And with the last touches and fills, we put it together, and it has become a masterpiece again.” The tale of Paul Thévenaz may be one of potential unfulfilled, but at Vizcaya, one promise has been kept.

1 Mary Louise Van Saanen, “Paulet Thevanas [sic], Painter and Rhythmatist,” Vanity Fair, August 1916, p. 49, available at oldmagazines.com. 2 Paul Thévenaz: A Record of His Life and Art Together With an Essay On Style By the Artist (privately printed by Alice DeLamar, 1922), pp. 129–132. 3 Witter Bynner, “A Poet’s Tribute to a Painter,” New York Times Book Review and Magazine, July 24, 1921, page 17.

BETH DUNLOP is the award-winning former architecture critic of the Miami Herald.