Two summer exhibitions explore works in the most elusive yet expressive of mediums

American watercolor painting, though never entirely neglected, is having a particular moment with an exhibition devoted to the medium at Harvard University’s Fogg Art Museum and an exhibition about the working methods of Georgia O’Keeffe at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. Although the MoMA exhibition features work in a number of media that O’Keeffe explored, watercolor emerges from both of these shows as an especially expressive medium. The two exhibitions are both team efforts by multiple curators who bring to bear a range of expertise that enables the group to explore, in the case of the Fogg, the diverse effects possible in one deceptively simple medium, and, in the instance of the MoMA show, to take seriously the materiality of O’Keeffe’s work. In so doing, MoMA draws attention to the artist’s dynamic use of watercolor, which suited her intense interests in landscape and atmosphere.

The great potential of watercolor, as the Fogg curators argue, lies in its very unpredictability: it is, they note, “a medium uniquely shaped by forces outside the artist’s control.” This fact was demonstrated to me recently by the Cuban-born artist Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons in her Nashville studio. As she embarked on a new watercolor painting, her hand hovered over the sheet of paper as she used a spray-bottle to wet the surface. Then she quickly distributed the pigment over the paper, after that standing back to watch where it pooled.

One can imagine Georgia O’Keeffe having engaged in a similar process to make a work like Blue Hill No. II (1916), on loan to MoMA from the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe. Produced during the short time she took summer classes and taught at the University of Virginia between 1912 and 1916, O’Keeffe “flooded the sheet with blue in order to describe the curve of a hill in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley.” The base of the hill is suggested by a lighter color blue, which blooms through what was evidently a particularly watery pool of paint, into the darker slope above it. Several depressions in the hillside are suggested by deep blue patches of watercolor. Although the contours of the Virginia hill seem to have resulted mostly from happy accidents, O’Keeffe’s control of the medium is obvious at the crest of the hill where a fine band of reserved white paper shows through to separate the land from the lighter sky above.

The use of a reserve, an area of paper where there is no paint and the base material—or support—shines through, is one of the strategies the Fogg show explores through examples by some of the acknowledged experts in the watercolor medium, including Winslow Homer, John Singer Sargent, Helen Frankenthaler and others. Additional “material matters” are also examined in the show, as well as in the accompanying catalogue, to provide a deep understanding of how those artists who excelled at watercolor were able to harness the various potentialities of the medium while avoiding its unique pitfalls. At the same time, the exhibition provides an overview of watercolor production from the 1880s to 1990; included in the works from the later decades are a number of small, abstract paintings by contemporary artist Richard Tuttle, whose essay “Six Sunday Thoughts on My Work with Watercolor” is published in the extensively illustrated catalogue.

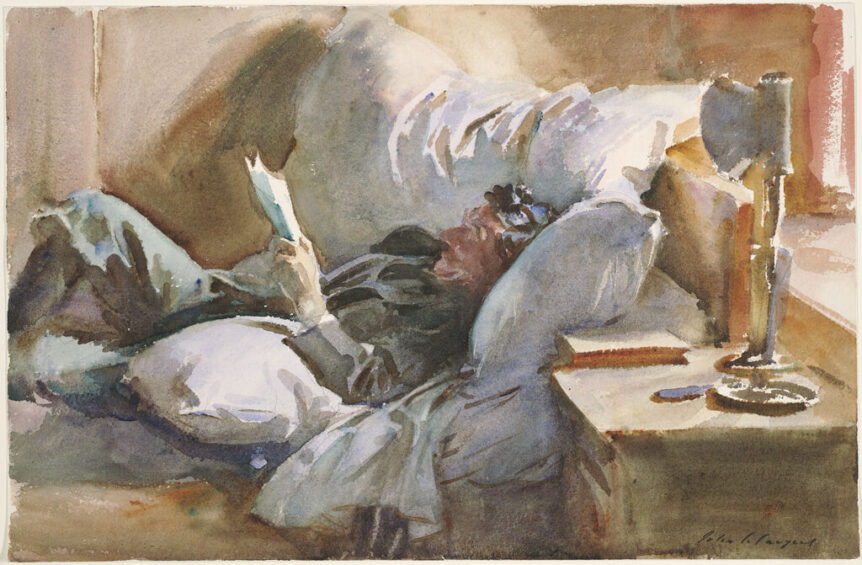

The Fogg curators point out that in the mid-twentieth century, “watercolor’s reach [extended to a] diverse array of artists, many of whom turned to watercolor to address challenging economic conditions, personal hardship, illness, and marginalization.” From the eighteenth century onward, the portability of the medium, and the relatively modest investment in materials it requires, had opened it to a wide range of practitioners, both amateur and professional. The exhibition emphasizes the latter, for instance, Sargent, whose mother, Mary Newbold Sargent, was a dedicated amateur watercolor painter, as Paul Fisher documents in his recent biography, The Grand Affair: John Singer Sargent in His World (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022). Fisher has attuned us to the psychological undercurrents of Sargent’s portraits, especially those that depict, often obliquely, his emotional intimacies with men. In Man Reading (c. 1905, Harvard Art Museums), now on exhibit at the Fogg, Sargent achieves a seemingly spontaneous and intimate picture of an unnamed subject, likely because the means of watercolor were so much more portable and less intimidating than those he mobilized for his famous Gilded Age society portraits.

Among the artists whose presence in the show demonstrates the diversity of practitioners of watercolor alluded to by the curators is Beauford Delaney, the African American painter whose work inspired James Baldwin to rhapsodize, in an essay written in 1964 for an exhibition of Delaney’s work, “that life, that light, that miracle are what I began to see in Beauford’s painting […].” For Baldwin, Delaney’s light had “the power to illuminate, even to redeem and reconcile and heal.” Given that Baldwin made this statement in the midst of the Civil Rights movement, his was a significant claim for the medium’s potential.

It is a potential that has not been completely realized, but some contemporary artists, of diverse backgrounds, are demonstrating how a medium sometimes associated with amateurism or merely decorative work, can be used to create expressive images in which the unique properties of watercolor draw in the viewer to offer some of the emotional experiences that Baldwin hoped paintings could. For instance, Campos-Pons uses watercolor to address her identity as a woman of color in the Global South. She also revisits some of the sites earlier watercolorists were drawn to, such as the Penobscot Bay region of Maine. Her large-scale watercolor, Untitled #4 (2012-17) records her vision of Swans Island, located between Deer Isle and Mt. Desert Island, both favored locales for early modernist painters in watercolor like John Marin whose work is featured at the Fogg. The very size of Campos-Pons’s watercolor starts to give the medium the “power” that Baldwin imagined for it. Like O’Keeffe exactly a century earlier, Campos-Pons explores the unpredictability of watercolor by allowing it to flow and bloom into darker and lighter areas, as a means of expressing the fluidity of the waters she depicts. Along the high horizon line, the artist perfectly captures the impression of the tiny, heavily wooded islands that seem to float on Penobscot Bay in midsummer. The image invites the viewer to immerse themself in it and to experience the peace and healing Baldwin hoped watercolor could achieve. More, as the image of a fragile landscape it is a call to value and preserve our natural world at a moment when it has never been so vulnerable.

Summer has always been a time for watercolor: the minimal and portable supplies required by the medium meant that artists could be nimble and capture many different views of multiple destinations. O’Keeffe, for instance, exhausted herself making watercolor pictures of the Virginia landscape in 1916, reporting, “Oh, I’m simply soaked with mountains of all kinds—So full I’m almost nauseated—Drunk with it.” In later summers, as the MoMA exhibition demonstrates, O’Keeffe would explore different landscapes, including places like coastal Maine, where other watercolorists were also drawn—both before and after her. In the work of O’Keeffe, as in that of other twentieth- and twentieth-century artists, watercolor depictions of the natural or human-made landscape coincide with, or sometimes eventually give way to, purely abstract paintings. For instance, in 1916 O’Keeffe also produced a pair of small-scale watercolors, titled simply Red and Blue (one on loan to MoMA from the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, and the other from the Myron Kunin Collection of American Art in Minneapolis). Such works which take as their subject the pigment itself, its interaction with the support, and the qualities of color and light the medium are capable of. They show the important—but often overlooked—place of the medium in the history of modern art.

American Watercolors, 1880-1990: Into the Light is on view at the Fogg Art Museum in Cambridge, MA, through Aug. 13, 2023 and Georgia O’Keeffe: To See Takes Time is on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York through Aug. 12, 2023