Jeremy Frey, master Passamaquoddy basket maker, has taken traditional Indigenous forms to new heights.

Long before catching the exhibition Jeremy Frey: Woven, originating at the Portland Museum of Art in Maine and now at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Connecticut, I was well aware of his Passamaquoddy community, not far from where I live during summers on the coast of Maine.

The tribe is one of five in the Wabanaki Confederacy, translated as “People of the Dawnland,” and I share with them, at our longitude, being among the first to witness the sunrise over America—a kind of liquid gold that edges over the horizon and, from where I see it, spills across a bay.

During my early Maine summers, I recall an older woman coming down the woodland path to my house carrying a large basket filled to the brim with smaller ones. This was my introduction to the Passamaquoddy technique of basket weaving with brown ash from the forests and sweetgrass harvested along the shores. Over the years, I purchased quite a few until she disappeared, and each summer I make a display of them—lidded boxes with spiky folded points or curls, earth-colored bowls, vase shapes with colored horizontal stripes.

Imagination was integral to those designs, which enhanced the practical with twists and colors in a long tradition of “fancy” baskets made by generations of Passamaquoddy women, a popular trade commodity from colonial times into the nineteenth century. Men, on the other hand, made the pack baskets slung over their backs for hunting or to stash into the bows of canoes, a practice archaeologists claim has lasted more than thirteen thousand years.

Jeremy Frey was born into generations of a renowned basket-weaving family, including his mother and first teacher, Frances “Gal” Frey, and he was in his twenties when, at her suggestion, he began at a workshop as a pounder, splitting ash wood for the baskets.

The exhibition’s excellent catalogue begins with the Wabanaki creation legend that Glooskap, a mythological figure, shot an arrow at an ash tree, and the tribe came out of the bark. No sooner did Frey master the technique of the fancy basket forms, first as an apprentice and then as a mentor, than his ingenuity kicked in, immediately raising possibilities of new shapes and molds and integrating other materials to a level not achieved by others.

The film Ash (2023), produced by Frey with filmmaker Joshua Reiman, follows Frey from his walk in the forest to select a perfect ash tree to the completion of a master basket. There is a quiet patience about the film as we see him carry a trunk out of the forest, watch him pound and then split the liberated lengths of wood with a knife into strips, sometimes down to 1/32 of an inch in diameter, like a thread. Finally, we observe the slow, seemingly inconceivable, meticulous weaving of the basket, using splints both natural and dyed in bright colors. Yet, there

is a pervasive sadness to the film in learning that the emerald ash borer, which first arrived in Michigan, is now decimating the brown ash in Maine, thus threatening the continuity of Frey’s art.

Frey’s early ash and sweetgrass fine-weave baskets remind me of my first purchases from the older woman, with points and curls, but already at a notch far above. His Basket within Basket, for example, his first of this genre, consists of five baskets inserted into one another, each with different exterior woven characteristics and designs. Or take his baskets inspired by the squat, spiny, globular shells called tests, from sea urchins, that are perhaps the most beautiful and variegated in color of the many shells that wash up on Maine beaches. Frey fabricated at least thirteen such baskets between 2007 and 2022. One can easily trace his evolution of the idea in them, building over time into a grand finale piece titled Green Point Urchin, with bright green points accentuated with black inserts against the natural tones of ash.

It is a marvel of interpretation. Frey is never at a loss for a new form or embellishment—no sooner does he reach completion of one, he says in Ash, than he has the next design in mind. He has remained completely sui generis in his art, despite being exposed to other traditions by attending national gatherings of tribal weavers over time. He has borrowed only one important element, his signature woven ring finial on basket covers, suggested to him by a native Hawaiian weaver who taught him how to make it.

Frey’s baskets—whether tall, bulbous, or squat in shape—are mostly woven with contrasting combinations in brilliant colors, like the alternating vertical turquoise stripes and horizontal blue folded points of Defensive. He often incorporates an array of other natural materials, including cedar and birch bark as well as porcupine quills, the latter woven into lids to depict the typical wildlife of Maine, such as loons, bears, or an eagle or blue jay. Frey’s so-called

double-walled baskets, in which one basket is nestled into another like a lining, are made using a brilliant technique that appears almost impossible to achieve.

In one, Navigating Tradition, the exterior strands of smooth natural ash, both light and dark, symbolizing bark, contrast with a vibrant interior of dark purple and red in checkerboard and striped designs. In another, Double-Walled Point Basket, colorful points of red with black linings spiral around the exterior, while the dark green and black checkerboard and striped patterns of the interior are separated by brown concentric circles.

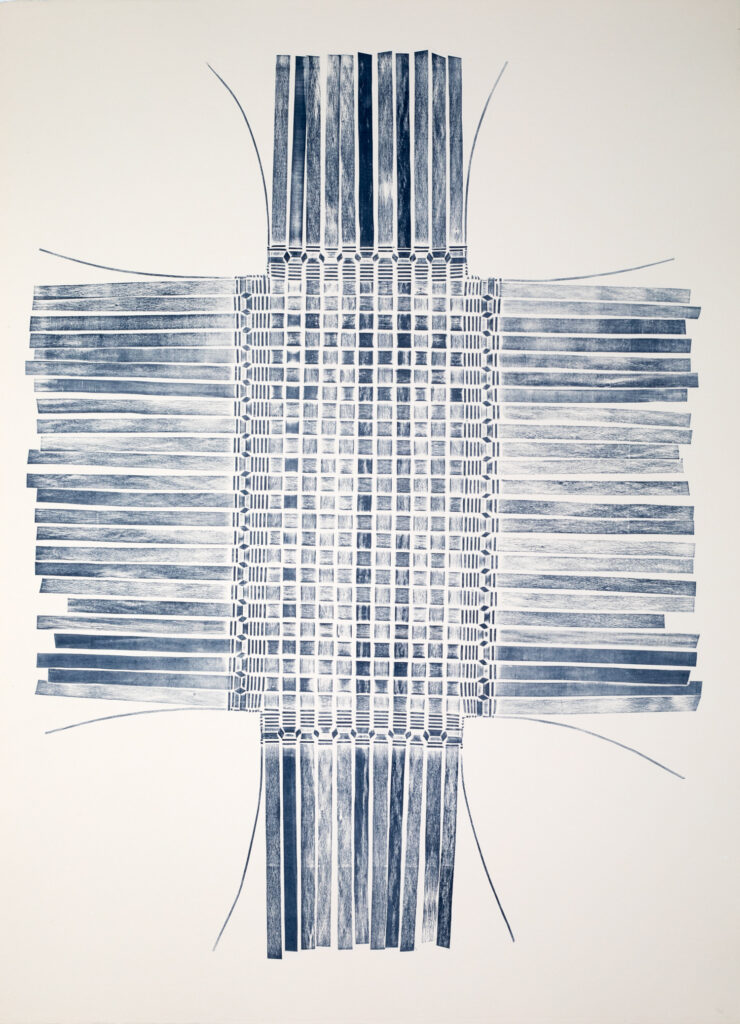

Beyond the baskets themselves, Frey’s work with the Wingate Studio, publishers of fine art etchings in New Hampshire, has yielded another method of studying his techniques—a revelatory series of monoprints of the layouts of his crisscrossed weaving patterns at the birth of a basket or woven box. Especially commanding is one with a round base and radiating splints.

Frey’s work brings to mind other utilitarian vessels that over time have evolved into art, not simply as archaeological remnants of their cultures, but as evolutions in their designs for beauty’s sake. I think of ancient urns that became priceless objects of display, no longer for storing wine. With Frey’s sculptures, we are witnessing a singular moment in basket-making history, when an artist takes the same materials and techniques utilized for centuries by others and refines them into a new form to stimulate visual appreciation and pleasure.

I cannot end this story without mention of one particular basket by Jeremy Frey called First Light. Woven into its round, multicolored lid is my sun rising through a red and golden streaked sky and spilling across a dark blue wavy sea. Here Frey has captured the Wabanaki dawn, symbolic of an entire oeuvre that is taking basket weaving into a new day.

Jeremy Frey: Woven is on view at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, Connecticut, until September 7.

PAULA DEITZ is the editor of The Hudson Review, a magazine of literature and the arts.