Fig. 1. Faith, Hope, and Love by Mary Lizzie Macomber (1861–1916), 1894. Signed and dated “M.L. Macomber/ –1894–” at upper right. Oil on canvas, 33 by 24 inches. Private collection; photograph © Roy Miles Fine Paintings/ Bridgeman Images. Collection; Roy Miles Fine Paintings.

Boston-based Mary Lizzie Macomber (pronounced MAK-um-ber) was among the late nineteenth-century American artists who closely emulated the figurative work of the English Pre-Raphaelites (Fig. 6). She was especially enamored of Dante Gabriel Rossetti and followed his example by painting decorative allegorical artworks depicting contemplative, ethereal young women in flowing gowns. Instead of the femmes fatales and fallen women in works by Pre-Raphaelite men, meant for the male gaze, Macomber created chaste and reverent embodiments of spiritual ideals.

While her works align with the typical construction of the feminine identity in the United States in the late nineteenth century—exhibiting qualities such as grace, refinement, gentleness, purity, and piety—she also took a symbolist approach. Probing a psychological, deeper realm of female experience, she made reference to and spoke to the women of her time, conveying their inner strengths, intellect, and sorrows. Macomber might have been chastised for impropriety in a more explicit type of art, but allegory provided her with a covert and flexible language, allowing her to circumvent patriarchal standards that demeaned women’s abilities and suppressed their aspirations.

Forgotten after her death in 1916, when European modernism dominated the American art world, Macomber’s intriguing, multidimensional art will receive long-overdue scrutiny in a forthcoming exhibition at the Fall River Historical Society in Massachusetts. The show will exemplify how the perspectives of American women artists—frequently omitted from the hierarchical art historical canon—are essential to a full account of the era’s art and culture.

Fig. 2. St. Catherine by Macomber, 1896. Signed and dated “M.L.Macomber./ 1896.” at center right and inscribed “Copyrighted.1896. by.M.L. Macomber” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 32 7/8 by 24 1/8 inches. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of the artist.

Private and reclusive, Macomber never married and was often unwell. In a self-portrait dated 1900, she appears dignified and, wearing an olive-colored velvet cloak with fur trim, dressed to go out in public (Fig. 3). Yet most of her face is in shadow under a broad-brimmed hat. Just as there are often double meanings in her art, here she is both seen and unseen. Macomber was said to have built walls around herself and at her death, she was memorialized as an artist whose life consisted of a “secluded and little heralded struggle for the realization of an ideal, of spiritual ethereal beauty.”1 However, she did seek recognition. From 1889 until her death, she actively showed her work in important annual exhibitions and expositions, receiving much attention and admiration. In 1893 two of her paintings were lent to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. In 1902 she was called “Boston’s famous woman artist” in the Boston Sunday Post. 2 In 1905 an article in the Providence Sunday Journal remarked: “Some critics even go so far as to acclaim [Macomber] the greatest woman artist in America.”3 Whereas many women artists struggled to be noticed, after 1901 Macomber was represented by Boston’s pre-eminent art dealer, Robert C. Vose, at the Vose Galleries (whose archives today hold images of her many sold and lost works). She also completed commissions for a devoted group of patrons.

Macomber was born on August 21, 1861, in Fall River, about fifty miles south of Boston, then the nation’s largest textile manufacturing center. (And where another notable Lizzie, the alleged axe murderer Lizzie Borden, was born a year earlier.) Although Macomber had distinguished Pilgrim and Quaker ancestors, her family belonged to the middle rung of Fall River society. Her father, Frederick W. Macomber (1825–1886), was a jeweler and watch repairer. He served as a deacon in Fall River’s First Congregational Church and wrote poetry in his spare time, an activity he encouraged his daughter to engage in as well. At age nineteen, over his objections, she decided to pursue an art career, studying privately with the still-life painter Robert S. Dunning (1829–1905). Macomber’s first works, now lost, were still lifes in the manner of Dunning, who took pride in her success and for whom she held enduring admiration.

Fig. 3. The Olive Cloak by Macomber, 1900. Inscribed “The Olive Cloak/ M. L. Macomber 1900” on the back. Oil on canvas, 27 5/8 by 22 1/8 inches. Private collection; photograph by Tim Pyle.

In the fall of 1884, Macomber gave up her Fall River studio to live in Boston. Enrolling at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts—where her instructors were Otto Grundmann and Frederic Crowninshield—she shifted her focus to the figure. When her father died in April 1886, she dropped out of school, reportedly due to a nervous breakdown. She then moved to a cottage in the Waverley section of Belmont, Massachusetts, a suburb of Boston, to live with her widowed mother, Mary W. Poor (1831–1906). While recuperating from her breakdown, Macomber set aside painting, but in December 1886 she began working for Art Amateur—the nation’s leading journal of, in the magazine’s term, “household art.” For four years, she also produced patterns for items such as portières and piano-stool cushion embroidery.

Macomber resumed painting in 1888 while studying under Frank Duveneck, during his brief spell teaching art in Boston. Working from posed models, and sometimes using herself as a model, Macomber produced two types of imagery: her own interpretations of religious and mythological subjects and allegories she invented. In the latter, instead of depicting preset symbols, she created unique personae and narratives. In a long article on her work, published in New England Magazine in 1903, the well-known Boston art critic (and Winslow Homer biographer) William Howe Downes lauded her originality, noting that instead of “certain graphic rebuses overladen with archaic symbols for the edification of the erudite,” Macomber was inspired by ideas of “real spiritual significance” in works “new to pictorial art.” Yet Downes also praised Macomber for work that remained within acceptable limits for a woman artist. He commended her for adhering to “the spiritual feelings and aspirations of her own sex.” He explained: “the soul of a woman is of a different order . . . from that of men” and observed that women failed as artists when they “folded their wings, and preferred to walk, rather than fly.” This, he reasoned, is because women “cannot walk so far as men.”4 Thus, Downes encapsulated the era’s biased view that women could be innovative, but only in a realm apart from the real world of achievement and productivity, which belonged to men.

Fig. 4. The Bearer of the Soul by Macomber, 1915. Inscribed “Macomber 1915/ Reproduction rights reserved” at upper right. Oil on canvas, 50 1/4 by 40 inches. Huntsville Museum of Art, Alabama, Sellars Collection of Art by American Women.

At the start of her career in the 1890s, Macomber’s art featured delicate color harmonies, soft contours, symbolic details, and grainy, fresco-like surfaces, suggestive of early Renaissance paintings, such as those of Botticelli and Fra Filippo Lippi. An example is Faith, Hope, and Love, exhibited at the National Academy of Design annual in 1895, in which she situated idealized representations of the three theological virtues in a pyramidal arrangement typical of a Renaissance altarpiece (Fig. 1). However, the women appear less beatific than joyless, concentrating with fixed, trancelike gazes. Here, Macomber perhaps suggests that virtue was not, in fact, innate to women, and instead requires cultivation and effort. The figure representing Love stares disconsolately at the crown in her lap—a hint that, for Macomber and all women, virtue could also be an unwanted burden.

Fig. 5. An Instrument of Many Strings by Macomber, 1897. Signed and dated “M L Macomber/ 1897” at upper right. Oil on canvas mounted to cradled wood panel, 34 by 29 1/2 inches (framed). Delaware Art Museum, Wilmington, F. V. du Pont Acquisition Fund.

Macomber highlighted female self-determination in St. Catherine, for which she won the 1897 Dodge Prize—awarded for the best painting by a woman— in that year’s National Academy of Design annual (Fig. 2). The work depicts Catherine of Alexandria, a fourth-century noblewoman in Roman-ruled Egypt, renowned for her intellect. On receiving a vision of the Virgin and Child, Catherine renounced the Roman gods and her many suitors in favor of Christianity and chastity, for which she was martyred. Whereas most artists showed this subject in the guise of Catherine’s “mystical marriage,” in which she is metaphorically teleported to the feet of the Virgin and Child and marries the latter—even though he is still an infant—Macomber used a painting as the vehicle of Catherine’s epiphany (no doubt a reference to her own means of life fulfillment). She also set the scene in Catherine’s era, including such details as a tiled floor, marble bench, Greek amphora, and wall mosaics—their spiked wheel patterns anticipating how Catherine would be tortured. With her face in profile, the haloed figure turns from her books to gaze at a painting propped against a pot. On close inspection, you can discern that it is a painting of the Virgin and Child, and Catherine seems to look directly at the Virgin, who, surprisingly, is a mirror image of her. The two women are dressed and posed alike. Macomber’s implication may be that Catherine’s self-awareness, not a religious vision, was the source of her enlightenment. In 1898 Macomber gave the painting to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Pre-Raphaelite influence is especially apparent in An Instrument of Many Strings, which was purchased in 2019 by the Delaware Art Museum, in recognition of its parallels to works in the museum’s large English Pre-Raphaelite collection—much of which was donated by the Delaware industrialist Samuel Bancroft Jr. (Fig. 5). The work resembles Rossetti’s Veronica Veronese (Fig. 6). Both paintings depict red-haired, long-necked women in green dresses, who listlessly pluck musical instruments—a violin in Rossetti’s painting and a kithara in Macomber’s. Using rich tones and textures inspired by the art of Veronese, Rossetti portrayed a languid subject listening to the song of a caged bird, implying her sexual longing. Macomber evoked Fra Angelico in her softer-toned image of an angelic figure with a gold halo behind her head. Showing her melancholic subject turning away from her instrument, Macomber suggests that, instead of hearing what she plays, she is listening to the music in her mind, which constitutes her real instrument of many strings.

Fig. 6. Veronica Veronese by Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828– 1882), 1872. Initialed and dated “D G R 1872” on desk at right. Oil on canvas, 58 by 49 3/4 inches (framed). Delaware Art Museum, Samuel and Mary R. Bancroft Memorial.

Fig. 7. Study for Isabella by Macomber, c. 1908. Oil on academy board, 8 by 5 inches. Fall River Historical Society, Massachusetts; Pyle Photograph.

A change occurred in Macomber’s art after the turn of the century. Proud of her Quaker and Protestant heritage, she was dismayed when her religious images led some to the assume that she was Roman Catholic. She subsequently focused on her invented allegories. Working in a more painterly style with a richer palette, she turned to ponderous themes of death and the power of memory “for good or ill,” often using her art to cope with her sustained grief at the death of her younger sister Jessie from rheumatic fever, when Jessie was twelve and Mary was sixteen.5 In Memory Comforting Sorrow—exhibited at the National Academy of Design in 1902—Sorrow, her head buried in her hands, is not soothed by the harp music played by a severe-looking Memory (in which the artist’s profile is recognizable) (Fig. 12). Macomber implies that while memories can preserve love, they can also intensify the pain of remembering a lost loved one. In Stella Maris—its title referring to the Virgin Mary as “a guiding star” on the way to Christ—and Night and Her Daughter Sleep of 1902, Macomber represented the Virgin as a protective spirit, easing the passage of a young woman’s soul from this life to the next (Fig. 8). In 1904 Macomber was sleeping in her studio in Boston’s Harcourt Building, when a fire broke out. After crawling down a smoky corridor, she escaped through a window to reach safety. Some of her paintings were saved but many were damaged or destroyed by the flames. Other artists who lost works in the fire include William Paxton, Joseph DeCamp, and William Worcester Churchill.

Fig. 8. Night and Her Daughter Sleep by Macomber, 1902. Oil on canvas, 30 by 24 7/8 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, purchase made possible by Emily Tuckerman.

In 1908, struggling to regain a sense of purpose, Macomber channeled her devastation into Isabella, in which she portrayed the grief-stricken protagonist in Keats’s 1818 poem, Isabella and the Pot of Basil, tenderly cradling the urn containing the exhumed head of her murdered lover (Fig. 7). In 1908, two years after her mother’s death, Macomber took her first and only trip to Europe. There she became an admirer of Rembrandt, an influence demonstrated in late works such as Rosamond the Fair, one her few medieval subjects (Fig. 10). She lived in New York from 1909 until 1911, when she returned to Boston.

Fig. 9. Stella Maris by Macomber, 1902–1903. Signed and dated “M L Macomber/ 1902–03” at upper right. Oil on canvas, 24 1/8 by 20 1/8 inches. Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Henry H. Sherman.

Fig. 10. Rosamond the Fair by Macomber, 1915. Signed and dated “Macomber –1915–” at upper left. Oil on canvas, 18 by 14 inches. Delaware Art Museum.

Macomber’s first solo exhibition was held at Vose Galleries in 1913. Among many reviews, one in the Boston Globe acknowledged her “very distinct place in American art” and affirmed her role as the “symbolist of life in the feminine.”6 In 1914 she was one of the original members of the Guild of Boston Artists, where a show of her art in the following year consisted of eight paintings, accompanied by sonnets she wrote (in the manner of Rossetti). One of the paintings in the show, The Bearer of the Soul, features a tiny, winged newborn soul, indicating its capacity for growth over the course of a lifetime (Fig. 4) Here Macomber makes reference to the belief she also expressed in her sonnet written to accompany another work in the show, Love and Memory, 1915: that only by developing inner strength could women find the consolation and meaning in life that would enable them to meet death with acceptance.

Her poem was prescient. On February 4, 1916, after resisting the aid of doctors and hospitals, Macomber died in her Boston studio from pneumonia at age fifty-four. Her Fall River funeral was attended by notable Boston artists, including DeCamp, John Joseph Enneking, Lilla Cabot Perry, and Bela Pratt. One month after her death, the City Art Museum in St. Louis held an exhibition of her work. “In the very recent death of Miss Macomber,” its catalogue stated, “American art has lost one of its noteworthy figures, whose life was spent in . . . a realization of an ideal, of spiritual ethereal beauty.”7 In her will, she left her estate to Robert Vose and cut out her elder brother, Walter (1855–1918), whom she had feared since childhood.

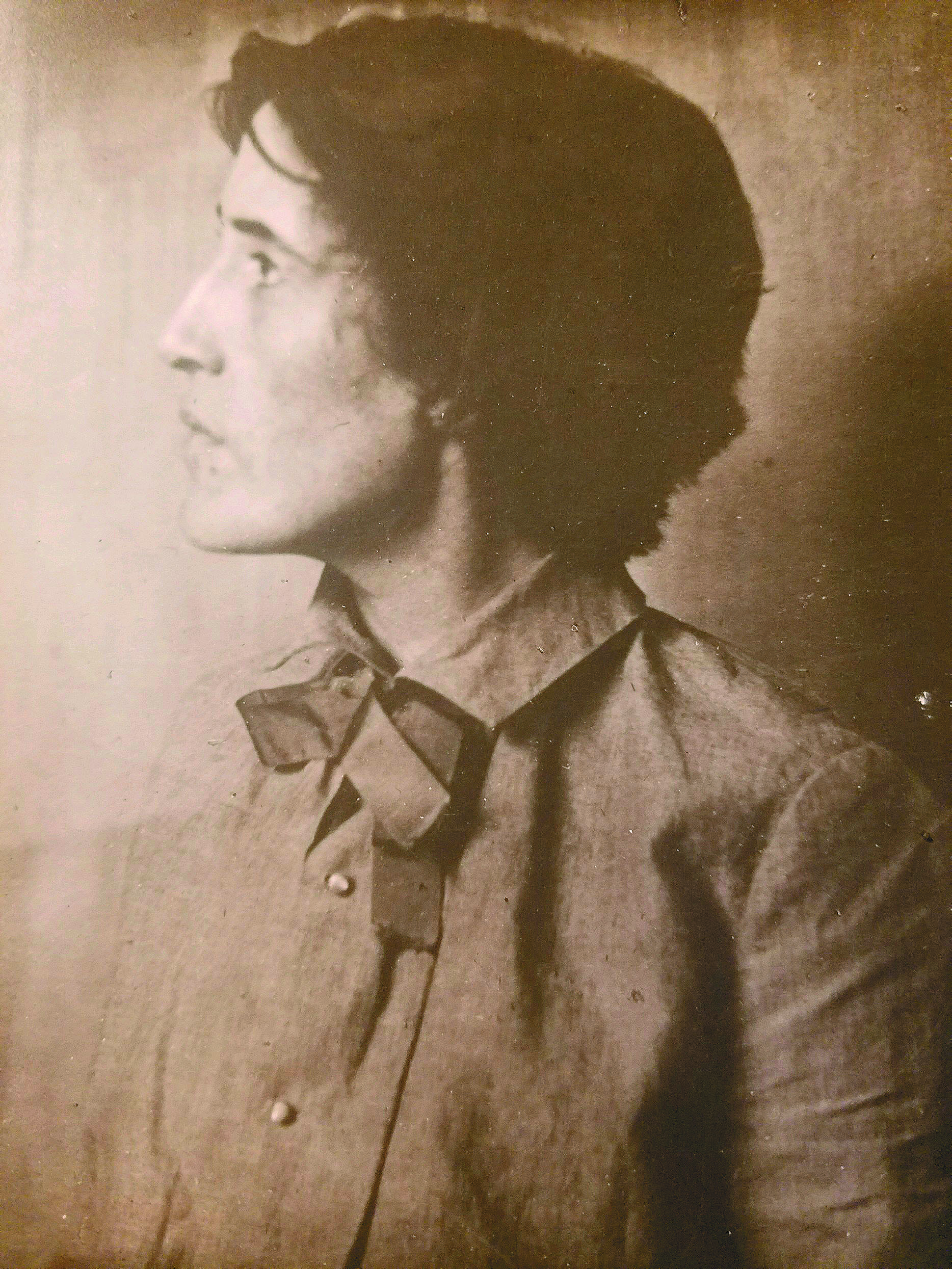

Fig. 11. Macomber in a photograph by Samuel Cooper Studios, Brookline, Massachusetts, 1903. Albumen print, 5 by 4 inches. Photograph courtesy of Vose Galleries, Boston.

An artist of understated perspicacity, Macomber found a means in the allegories she rendered that, in being deceptively unthreatening in their feminine subject matter, granted her the creative leeway to express messages of female empowerment. In her original art, constant productivity, and acclaim, she proved—contrary to Downes’s belief—that women could, indeed, fly and walk at the same time.

For consultation on Macomber’s life and art, thanks are due to Carey Vose, director, and Courtney Kopplin, gallery manager, Vose Galleries, Boston; Michael Martins, curator, Fall River Historical Society; and Heather Campbell Coyne, chief curator and curator of American Art, Delaware Art Museum.

1 An Exhibition of Paintings by Mary L. Macomber (St. Louis, MO: City Art Museum of Saint Louis, 1916), p. [2].

2 “New Works by Mary Macomber: Boston’s Famous Woman Artist,” Boston Sunday Post, Oc- tober 5, 1902, p. 24.

3 “Imaginative Work of a Boston Woman,” Prov- idence Sunday Journal, October 22, 1905, p. 28.

4 William Howe Downes, “Miss Macomber’s Paintings” New England Magazine, vol. 29, no. 9 (November 1903), pp. 282–283.

5 From her unpublished 1915 sonnet, “Love and Memory.” A handwritten copy of the poem is at- tached to the painting’s frame.

6 A[nthony] J. Philpott “Exhibition of Paintings by Mary L. Macomber,” Boston Globe, March 8, 1913, p. 9.

7 An Exhibition of Paintings by Mary L. Macomber, p. [2].

Fig. 12. Memory Comforting Sorrow by Macomber, 1901–1905. Signed and dated “M L Macomber 1901–05” at upper right. Oil on canvas, 30 by 25 inches. Fall River Public Library, Massachusetts; Pyle photograph.