When Edith Gregor Halpert opened a gallery in Greenwich Village in 1926, the art world was a different place. New York was not yet its capital; Paris was. Only a handful of commercial art galleries in Manhattan dealt with American art, then narrowly defined as art with an American subject by an American-born artist, usually long dead, such as Winslow Homer and the painters of the Hudson River school.

Halpert, however, firmly believed in the quality of the American art of her era. Her aim was to teach her fellow citizens to value the art of their own country, in their own time. Over the forty-three years of her career, Halpert’s Downtown Gallery represented a diverse group of artists, working in a variety of styles—women, Jews, immigrants, and artists of color, from Stuart Davis and Ben Shahn to Georgia O’Keeffe and Jacob Lawrence. She believed ardently that American art, like America itself, was pluralistic.

Edith Halpert and the Rise of American Art, a forthcoming show at the Jewish Museum in New York, explores her groundbreaking career. The following excerpt from the exhibition catalogue describes Halpert’s relationship with the great patron of the arts Abby Aldrich Rockefeller. Halpert helped to introduce her to both American modernism and to folk art, and Rockefeller in turn was, of course, instrumental in the founding of two of the premier cultural institutions in both fields: the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum at Colonial Williamsburg.

Not all art was difficult to sell. In January 1928, two months after Stuart Davis’s first solo show at the Downtown Gallery, Halpert had her first runaway success with an exhibition of American landscapes, a sweeping survey of the genre going back to 1848. Her intention was to demonstrate that painters of the younger generation could hold their own against such venerated masters as Childe Hassam and George Inness. For this project Halpert sought loans from fellow dealers and friends. One of them, the architect Duncan Candler, was able to borrow Winslow Homer’s Shark Fishing (1885) from a private collector who chose to remain anonymous. Halpert hung this riveting watercolor in an alcove alongside a contemporary example by William Zorach and an early mountainscape by John Marin, the latter on consignment from the gallerist Alfred Stieglitz.

One visitor offered a phenomenal $14,000—over $200,000 today—for Homer’s Shark Fishing, but to Halpert’s dismay she was told the anonymous owner was not interested in selling. A few days later, an unassuming, elegantly dressed middle-aged woman came to the gallery to inquire about the Zorach and Marin that flanked the Homer watercolor. “They are not for sale,” lamented Halpert. “I am holding them for the idiot who refused to sell the Homer for so much money.” “I am the idiot,” the woman replied. It was Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, daughter of the late Nelson Aldrich, who had been a powerful senator and one of the country’s wealthiest men, and now wife of John D. Rockefeller Jr., heir to the Standard Oil fortune. She promptly purchased the Marin and Zorach.1

It should come as no surprise that Abby Rockefeller and Halpert became fast friends. The heiress was an advocate for the rights of women, Jews, and African Americans. Her patronage of the Downtown Gallery’s spirited young director and diverse artists was, in some sense, an extension of her social activism. But above all she was an audacious collector of art, particularly (and in contrast to her husband’s enthusiasms) modern and contemporary work. Rockefeller became Halpert’s client in 1928, and she spent more than $20,000 at the Downtown Gallery in that year alone.

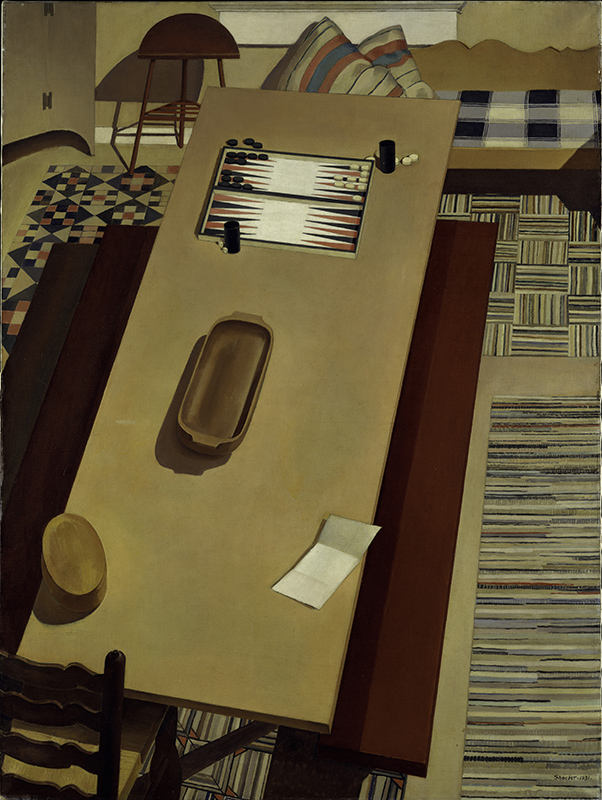

Rockefeller did not make big, expensive purchases. Instead, she preferred small works—watercolors, drawings, and especially prints—by as many artists as possible, Peggy Bacon, Walt Kuhn, Charles Sheeler, and Max Weber among them. Halpert also established a lucrative side business with her; in the summers when she traveled to Europe she would buy paintings and prints by French artists—Pablo Picasso, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Georges Rouault, Pierre Bonnard—for her client on commission.

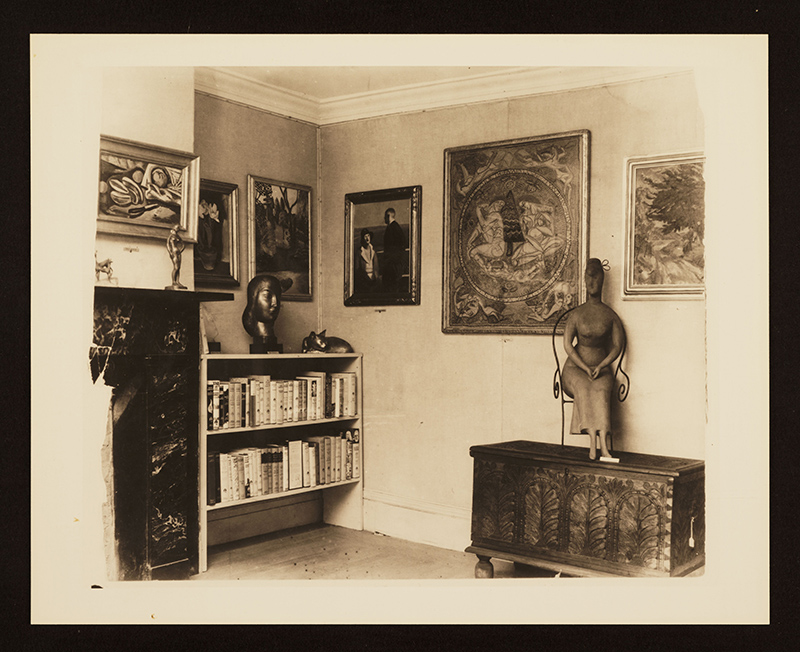

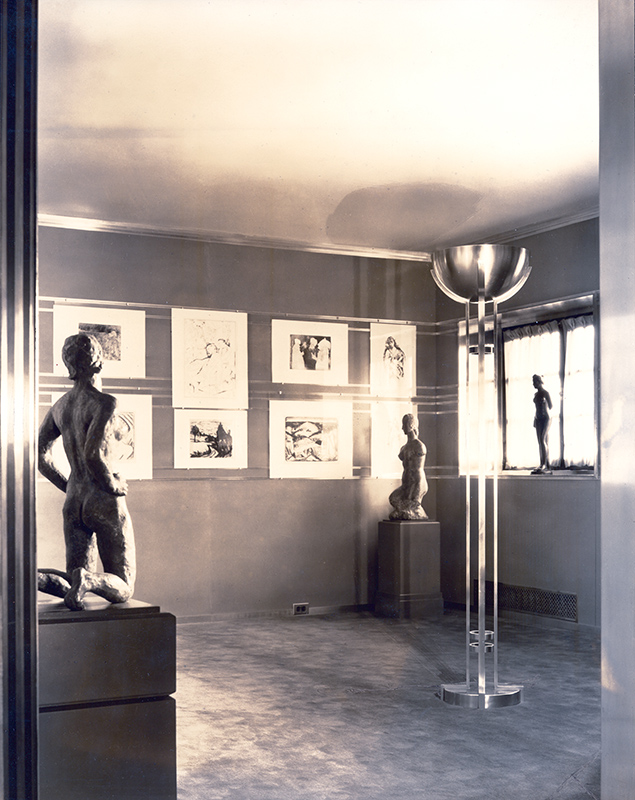

Rockefeller became the patron saint of the Downtown Gallery in its early years; in turn, Halpert became her most trusted art advisor. The young gallerist persuaded her client to build a private gallery in her Fifty-Fourth Street town house, and commissioned Donald Deskey to design the interiors, done in gray Bakelite walls with matching carpeting. Horizontal channeled metal strips on the walls allowed artworks to be changed easily; Halpert later imitated this system in her own gallery. Over the years Rockefeller’s Topside Gallery was filled with modern and folk art purchased under Halpert’s guidance.

Following on this success Halpert began to encourage Rockefeller to turn her personal passion for collecting into a public good. She suggested that Rockefeller spearhead a committee of ten women who would each contribute $10,000 annually to a fund for living American artists. The art purchased with their contributions could be exhibited in a small gallery within the Metropolitan Museum of Art, she proposed—an experimental concept that might lead to a more robust contemporary art program there down the line. “I shall not go into the needs for such a collection in our metropolis—the logical art center of this country,” Halpert wrote to Rockefeller in June 1929, but she did stress the importance of women being involved in this scheme. Many of her top clients at this time were society women—Edith Wetmore, Mary Quinn Sullivan, Aline Liebman—who, she thought, were more receptive than most men to the American avant-garde. “To me it seems fitting that women should foster this plan. Tradition points to greater courage in women towards reform and new ideas. . . . Women have more time to devote to the arts as can be judged from the attendance at all art functions.”2

In fact, Abby Rockefeller had already been thinking along these lines, but even more ambitiously. In the winter of 1928 she, together with her fellow art collectors Lillie P. Bliss and Mary Sullivan, began to form a plan to build their own progressive New York institution, not bound by the conservative tastes of the Metropolitan. At this Museum of Modern Art they would be able to exhibit and eventually donate the kind of contemporary art they felt deserved attention. The new museum opened to the public on November 7, 1929, just a few days after the stock-market crash that precipitated the Great Depression. Eventually, the bulk of Rockefeller’s modern art collection—two thousand works, including sixteen hundred prints—was given to the museum. Of these, at least 550 had been purchased from, or on the recommendation of, Edith Halpert.

Abby Aldrich Rockefeller was not alone. In the boom years before the Depression, as cities across the United States were expanding, affluent collectors of art were contemplating the founding of public art galleries and other arts institutions. Of these, many began to pay attention to American artists, often through the efforts of Halpert. The number of new museums whose founding collections were shaped or influenced by her is startling. In this early period her clients included Duncan Phillips, founder of what is now the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC; Edward Root, the Hamilton College arts professor who left significant collections to both the Munson-Williams-Proctor Arts Institute and the Metropolitan Museum of Art; and Louis E. Stern, a New York City lawyer and avid collector of nineteenth- and twentieth-century French art, who became interested in the Downtown Gallery through his love of prints. His collection of more than three hundred artworks was later bequeathed to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Others were to come.

This did not happen by chance. From the outset, Halpert had sought clients outside New York, advertising in national arts magazines. Through lengthy correspondences she developed relationships with collectors across the United States, as far away as California. William Preston Harrison, for example, purchased a number of watercolors for his local public art gallery, now the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “Los Angeles certainly has cause to be indebted to you for your generosity and good taste,” Halpert wrote to him in January 1927. “If every municipality had a Preston Harrison, art would not be the almost ‘unknown quantity’ [it is] in this country—limited to those few who not only have understanding but who care to express themselves.”3 It was her goal to find them all.

Edith Halpert and the Rise of American Art will be on view at the Jewish Museum from October 18 to February 9, 2020. This article is excerpted and adapted from the exhibition catalogue, Edith Halpert, the Downtown Gallery, and the Rise of American Art, by Rebecca Shaykin (Jewish Museum, New York, in association with Yale University Press, 2019). Reprinted by permission.

1 Halpert was very fond of this anecdote and repeated it often. There is, however, a record of Rockefeller visiting the gallery a month earlier than the opening of the landscape show in January 1928, with her son Nelson; see Diane Tepfer, “Edith Gregor Halpert and the Downtown Gallery, 1926–1940: A Study in American Art Patronage,” PhD diss., University of Michigan, 1989, pp. 289–293. 2 Edith Halpert to Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, June 5, 1929, Archives of American Art, Downtown Gallery Records, reel 5490, frames 976–977, cited in Lindsay Pollock, The Girl with the Gallery: Edith Gregor Halpert and the Making of the Modern Art Market (New York: PublicAffairs, 2006) 3 Edith Halpert to William Preston Harrison, January 12, 1927, AAA Downtown Gallery Records, reel 5490, frame 679.

Rebecca Shaykin is an associate curator at the Jewish Museum