A New York gallery maven and a forward-thinking collector, both women, drew the boundaries of the new field of American folk art collecting.

In May 1950, The Magazine ANTIQUES debuted its first issue dedicated to American folk art. Editor Alice Winchester invited a dozen leading voices to define the contours of the emerging field. One of the entries was sunvited a dozen leading voices in the field to define the contours of the emerging field. One of the entries was submitted by powerhouse dealer Edith Halpert, who opened her comments with the following quip: “Fortunately for historians, professional writers, curators, and technical experts, there are no absolute definitions in art, and not many indisputable attributions—not even a standard terminology.” [1]

Halpert’s tactfully open-ended declaration served a practical purpose. She had partnered with sculptor Berthe Kroll Goldsmith to purchase a gallery space at 113 West 13th Street in New York’s Greenwich Village in 1926. The accessible downtown location targeted middle-class buyers who lived in modest homes. There, Halpert displayed works by artists such as Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Elie Nadelman, William and Marguerite Zorach, and others, alongside carved and painted colonial furniture, bookcases, fireplaces, and other domestic trappings not typically found in museums.

It was no coincidence that the gallery was populated by both artworks and antiques. Halpert and her artist friends, many of whom she met through Hamilton Easter Field’s artists’ colony in Ogunquit, Maine, had summer residences furnished with inexpensive, rustic decor found in barns, yard sales, and local resale shops. William Zorach would recall in his autobiography, “All of us were picking up early American furniture and antiques. Not only were they much more beautiful than the regular manufactured products but they were much cheaper.” [2] Many of the Ogunquit artists, most notably Kuniyoshi, integrated these vernacular forms, such as furniture and weathervanes, into their compositions.

In 1929 Halpert established a gallery on the second floor of her building on West 13th Street that sold folk art and such “Americana” as weathervanes, figureheads, trade signs, and more. The bold silhouettes, bright colors, and utilitarian aspects of these selections complemented the formal qualities of the contemporary works offered in her downstairs gallery. In her insightful 2019 exhibition catalogue Edith Halpert: The Downtown Gallery and the Rise of American Art, Rebecca Shaykin noted: “For Halpert, there was no conflict in focusing on both folk and contemporary art. Not only were sales of Americana helping to keep her business alive, folk art acted as a ‘puller-inner,’ a kind of art perhaps more readily appealing to many potential buyers, who might then be exposed to more challenging work by her modernists.” [3] Perhaps just as important, the lower price points of these decorative objects appealed to consumers in the wake of the stock market crash of 1929.

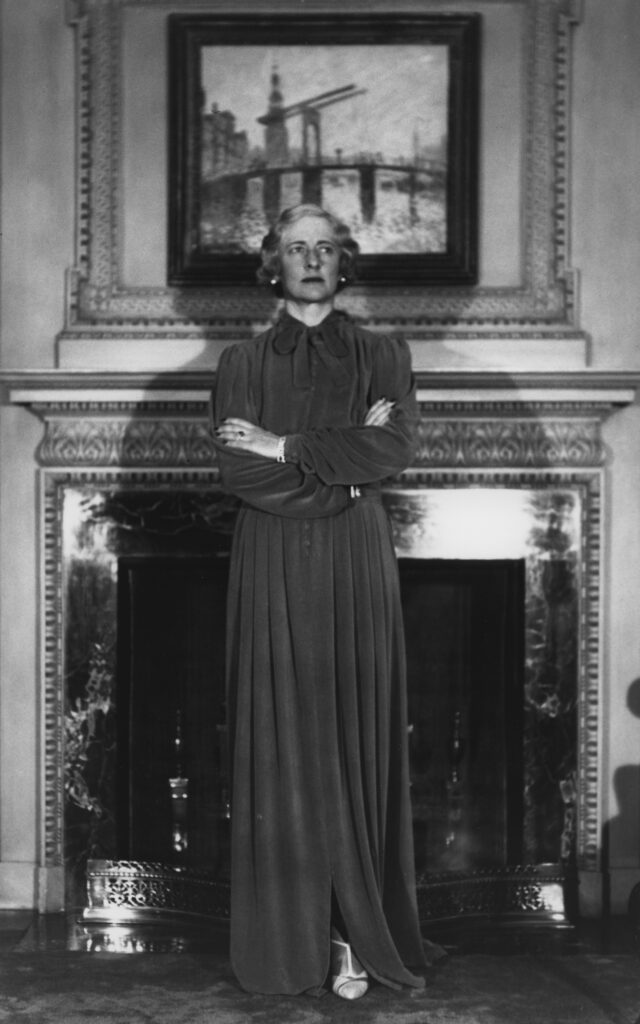

Halpert deftly weathered the economic vicissitudes of the 1930s, successfully marketing both folk art and modern fine art to adventurous collectors. Clients ranged from first-time buyers to elite patrons like Abby Aldrich Rockefeller. In 1940 she decided more space was required and moved to East 51st Street in Midtown. By 1941 her enthusiasm for American art and objects had reached Electra Havemeyer Webb, a sugar heiress and collector with a penchant for the avant-garde.

The daughter of Louisine Waldron Elder and Henry Osborne Havemeyer, Electra was born in 1888 to the kind of privilege afforded by America’s Gilded Age. Her parents were energetic collectors of Asian ceramics, Dutch Old Master paintings, French impressionism, and more. As a young child, a rare double portrait of Electra and her mother was executed by Mary Cassatt, a good friend of Louisine. Artworks by Paul Cézanne, Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, among others, surrounded Electra as she came of age.

While her parents had successfully imparted a love of art to their daughter, what Electra decided to collect caused some consternation. According to family lore, Electra was at Hilltop, the family home in Stamford, Connecticut, in 1907, when she spotted a carved and painted shop figure—what she called a “cigar store Indian”—outside a nearby shop. She purchased the figure for fifteen dollars and arranged for its delivery. Upon its arrival, Louisine reportedly asked Electra, “What have you done?” [4] Electra kept the figure despite her mother’s protests, fondly naming it “Mary O’Connor” after her governess (Fig. 3).

In 1910 Electra married James Watson Webb, a scion of the Vanderbilt family. Living between residences on Long Island, New York City, and Shelburne, Vermont, Electra continued to collect. She recalled, “all the time I was trying to find old wallpapers, furniture, rugs and prints that would look well . . . the closets and attics were filled. I just couldn’t let good pieces go by—china, porcelain, pottery, pewter, glass, dolls, cigar store Indians, eagles, folk art. They all seemed to appeal to me.” [5] For many years, she displayed her collection of “American folk sculpture”—which included many purchases from Edith Halpert—at the tennis court at her home in Westbury, Long Island. In the mid-1940s the Webbs began preparing the Westbury house for sale and devoted more energy to their home in Vermont. Shelburne Museum was incorporated in 1947.

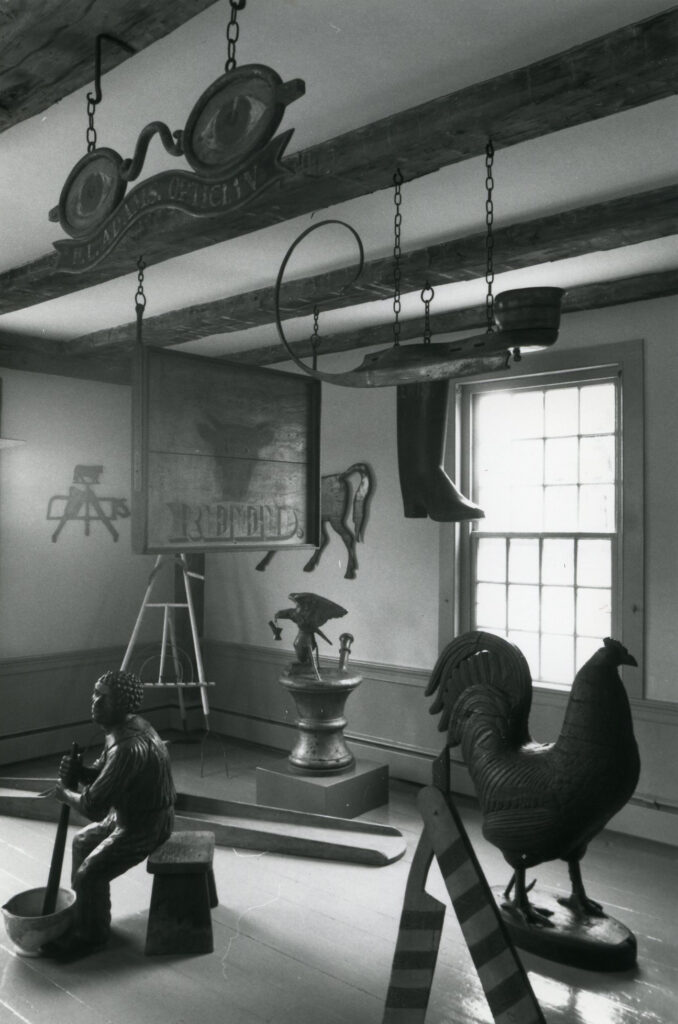

Conceptualized as “an educational project, varied and alive,” the museum provided a convenient outlet for displaying and sharing the “collection of collections” Electra had gathered over previous decades. The museum grew to include everything from buildings and boats to furniture, textiles, ceramics, glassware, paintings, sculpture, carousel figures, tools, and more. One of the things that distinguished the institution was its embrace of everyday material culture not necessarily tied to the histories of America’s elite. When the museum opened to the public in 1952, there were an estimated nine thousand objects exhibited in nine buildings.

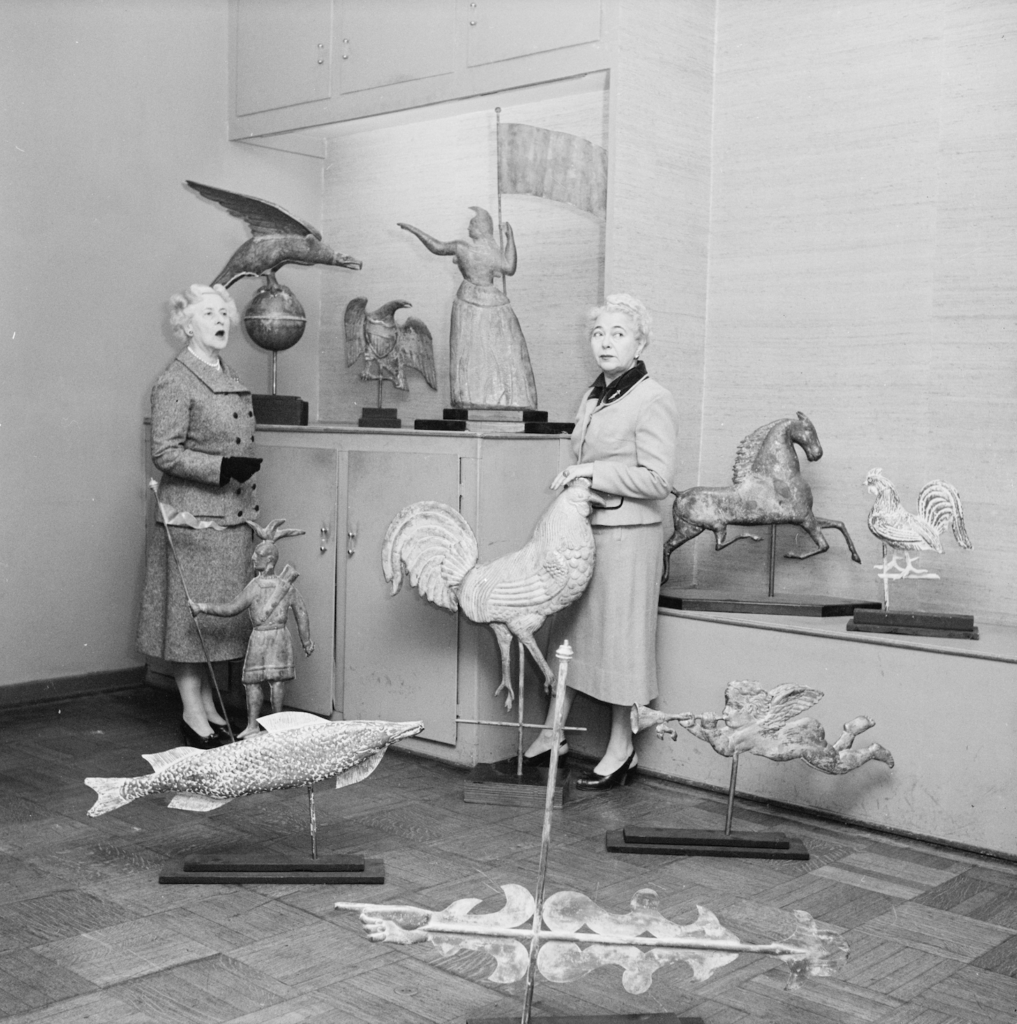

In June 1950 Edith had formally announced her connection to Electra by organizing A Museum Collection: Folk Art Sculpture, a show that served two purposes. First, it presented utilitarian, vernacular, folk art objects in a sanitized context typically reserved for fine art: weathervanes and carved figures were presented in clean, modern, spaces that connoted a formal museum gallery. Second, the exhibition provided a preview of what was soon to come at Electra’s vast museum.

While Electra Webb worked with a range of dealers and collectors, her relationship with Halpert was unquestionably the most critical for defining the museum as a center for American folk art. Edith frequently sent lists of objects on offer to Electra with specific thoughts on how a particular piece might distinguish a gallery or drive a narrative. In turn, Electra turned to Edith when she had questions about the fuzzy contours of what, exactly, constituted the relatively new field of “folk art.”

On the heels of the museum’s premiere, On the heels of the museum’s premiere, Electra wrote, “what [category] do you suggest for furniture with early stenciling and early painting. Does this come under Folk Art, and if so what category. Then I am starting to sort out quilts. Some I believe are Folk Art, and some are just quilts. I find it is very hard to decide what is folk art as I visit other collections.”[6] Electra trusted Edith’s judgment and keen eye so much that she affectionately referred to the dealer as Shelburne Museum’s “Fairy Godmother.”

In addition to more traditional, nineteenth-century folk sculpture, Edith encouraged Electra to expand her collection of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century American paintings. In the last decade of her life, Electra purchased paintings from of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century American paintings. In the last decade of her life, Electra purchased paintings from Halpert as well as dealers and collectors like Harry Shaw Newman and Maxim Karolik. Her collection of American paintings grew to include works by established American artists like John Singleton Copley, Thomas Cole, and Winslow Homer, as well as extraordinary portraits, landscapes, and marine paintings by lesser known “folk” painters such as Erastus Salisbury Field, William Matthew Prior, and James Bard. The bifurcated nature of Electra’s painting collection was by design; she would later explain, “only by contrast between the work of the untutored and the formally trained can one comprehend and study the development of art in America.” [7]

In May 1952 Edith reached out to Electra, imploring her to consider works by twentieth-century modern artists, writing: “To me, the link between folk art and modern art is very strong, and I am convinced that the Shelburne Museum as a whole will not only serve as a living document of past achievement but will also inspire contemporary artists and craftsmen toward higher goals.”[8] Edith was relentless, sending along books about modern painters Arthur Dove and John Marin, and encouraging Electra to see connections between past and present. Archival documents reveal that she was receptive, writing to Edith to ask her opinion about artists including Thomas Hart Benton, George Inness, Thomas Eakins, Jack Levine, Reginald Marsh, Paul Manship, Malvina Hoffman, and others.[9]

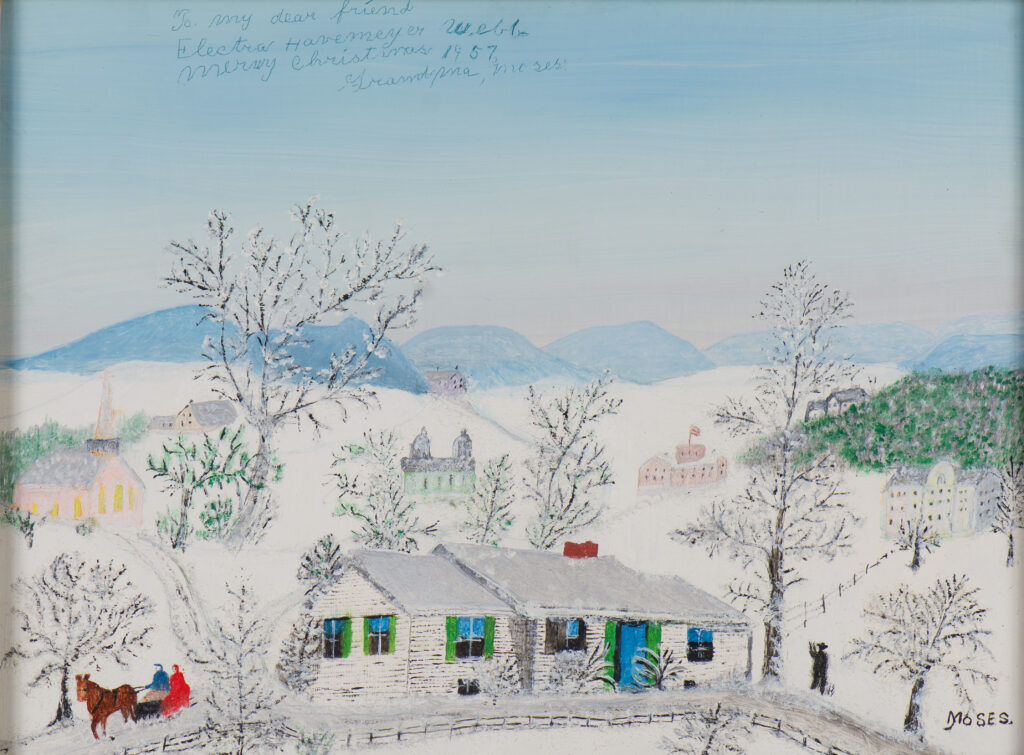

By the late 1950s, whatever reservations Electra might have had about acquiring modern art by living artists for the museum had evaporated. She had spent several decades patronizing the young Italian American painter Luigi Lucioni, whose photorealistic portraits, still lifes, and landscapes became synonymous with twentieth-century realism in northern New England (Fig. 10). When the state-of-the-art Webb Gallery of American Art at Shelburne opened in 1960, in addition to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century paintings and antique furniture, visitors could enjoy paintings by Anna Mary Robertson “Grandma” Moses.

Just aJust as the Webb Gallery was being prepared for opening, Halpert sent a selection of artworks for Electra to consider, among them William Harnett’s Merganser; Walt Kuhn’s Bareback Rider; Kuniyoshi’s Festivities Ended; two unnamed works by Marin; Georgia O’Keeffe’s Poppies; Charles Sheeler’s Composition around Yellow #2 (1958) and Sun, Rock, and Trees (1959); and an unnamed painting by John Sloan.[10] [FN] In addition, she sent

These artworks aligned with many of the overarching themes and collections that already characterized Electra’s museum. Harnett’s Merganser was a tour de force of technical ability that related to her collections of decoys and her enthusiasm for waterfowl hunting. Kuhn’s Bareback Rider and Kuniyoshi’s Festivities Ended, a haunting vision of a deserted carnival painted at a time of intense American xenophobia and racism toward Japanese Americans, linked to the extensive collections of carousel figures and circus ephemera that populated the campus (Fig. 13). Paintings by Sheeler and O’Keeffe bound the bright colors and flattened perspectives of folk art to the museum’s gardens and rolling lawns dotted by lilacs and apple trees. Zorach’s New Horizons was perhaps the most poignant, with its emphasis on the bond between a mother and her child, a kind of coda to Mary Cassatt’s double portrait of Louisine and Electra done so many years earlier.

In the months following Electra’s unexpected death in November 1960, her son, James Watson Webb Jr., returned almost all the modernist works to Halpert’s gallery, feeling they did not fit the historical flavor of the museum.[11] Even so, Halpert continued her involvement at Shelburne Museum as a trustee and tireless advocate for American art.

Today, Shelburne Museum’s collection counts more than a hundred thousand objects displayed across thirty-nine buildings and forty-five acres in Vermont’s Champlain Valley, continuing to collect and present exhibitions with Electra Webb’s expansive vision in mind. Recent acquisitions of artworks by Stephen Hannock, Norman Rockwell, Harold Weston, and more reflect regional visual cultures of New England and larger histories of American creative expression.

Moreover, Halpert’s suggestion that the museum might serve to inspire living artists and craftspeople has held steady. Exhibitions of contemporary work by Karen Petersen, Paul Scott, David Sokosh, Mara Superior, William Wegman, and more draw from the past while reframing the present, providing opportunities for wonder, conversation, and exploration of America’s myriad material histories.

KATIE WOOD KIRCHHOFF is the Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen Curator of American Decorative Arts at the Shelburne Museum, where she focuses on its pre-1945 collections of American fine, folk, and decorative arts.

[1] “What is American Folk Art: A Symposium,” The Magazine ANTIQUES, May 1950, p. 358. [2] William Zorach, Art is My Life: The Autobiography of William Zorach (Cleveland, OH: World Publishing Company, 1967), p. 88. [3] Rebecca Shaykin, Edith Halpert, The Downtown Gallery, and the Rise of American Art (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019), pp. 100–101. [4] Quoted in Lauren B. Hewes and Celia Y. Oliver, To Collect in Earnest: The Life and Work of Electra Havemeyer Webb (Shelburne, VT: Shelburne Museum, 1997), p. 9. [5] Quoted ibid., pp. 17–18. [6] Electra Havemeyer Webb to Edith Halpert, June 2, 1952, folder 1952, box 9, Electra Havemeyer Webb Papers, Shelburne Museum Archives, Vermont. [7] Quoted in Bradley Smith, foreword to Lilian Baker Carlisle, Inaugural Selection of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century American Art at Shelburne Museum (Shelburne, VT: Shelburne Museum, 1960), p. 1. [8] Halpert to Webb, May 8, 1952, folder 1952, box 9, Electra Havemeyer Webb Papers, Shelburne Museum Archives. [9] Electra Havemeyer Webb, “Moderns I like,” before 1960, folder 36, box 3, Electra Havemeyer Webb Papers. [10] Edith Halpert to James Watson Webb Jr., July 24, 1961, Correspondence with Downtown Gallery 1960–1961, box 24, Electra Havemeyer Webb Papers. [11] James Watson Webb Jr. to Halpert, August 29, 1961, ibid.