Posters calling for federal farm benefits. A warning that “Inflation means Depression.” Paintings of bombed villages and starving children. A look inside a prenatal clinic and a plea for care. The themes of Ben Shahn’s work are certainly relevant today. Is that a strong enough word? Prescient? Prophetic? Frustratingly routine?

Through his long career, Ben Shahn consistently trained his eye on human rights. And though the first stop of this exhibition at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid was timed to coincide with the 125th anniversary of the artist’s birth, the adapted show’s May opening at New York’s Jewish Museum is well-timed to meet our own particularly fraught moment. As show curator and professor of art history at James Madison University, Laura Katzman, writes in the catalogue, “Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity highlights the currency of Shahn’s art and its continued relevance by focusing on the artist’s commitment to social justice, through the lens of contemporary diversity and equity perspectives.” Or as Shahn put it, writing in 1966: “[William] Blake, in ‘Marriage of Heaven and Hell,’ said that righteous indignation over injustice was the truest worship of God. And I guess I am filled with righteous indignation most of the time.”

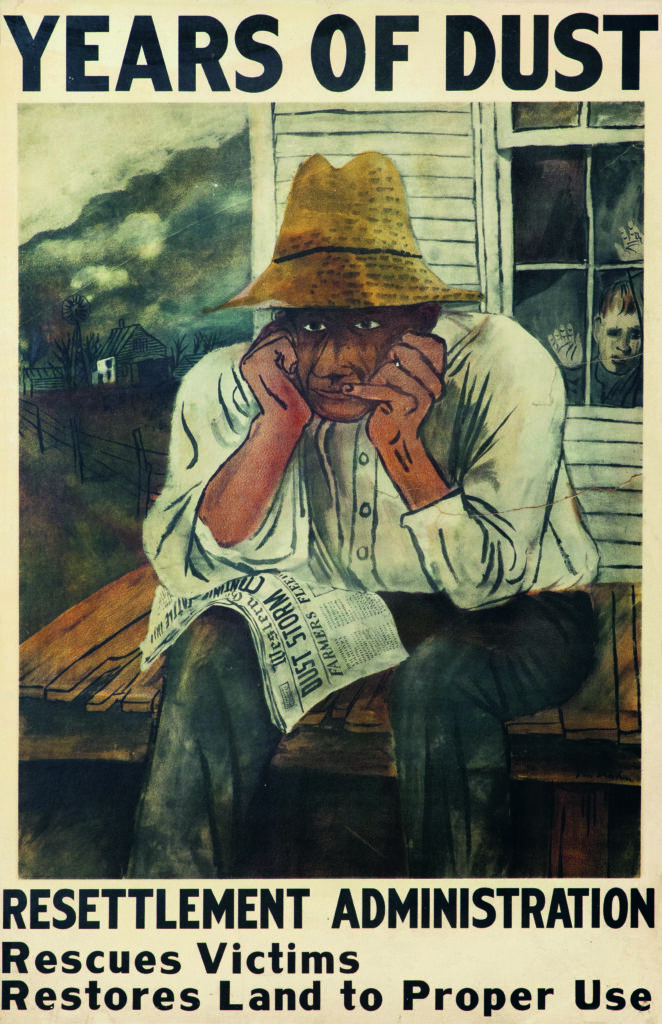

Whether his gaze was leveled on the effects of the Great Depression and the New Deal, the rise of fascism and the destruction of World War II, the nuclear arms race and the Cold War, civil rights, or workers’ rights, Shahn strove to document his era’s conflicts in a way that was widely accessible, both in its emotional resonance and through the wide visibility of his murals and posters.

Shahn’s family emigrated from Russian-held Lithuania in 1906, and his early training was as a lithographer. That launchpad comes as no surprise in the exhibition’s section titled “A New Deal for Art,” which examines his early work as a traveling photographer and creating murals and mass-produced posters for various government projects.

He had an affinity for lettering and languages that influenced this graphic work and would follow him throughout his career, even as he explored different mediums and more abstract styles. Another section of the show, “Spirituality and Identity,” studies Shahn’s lyrical later work in which typography frequently references the biblical stories and Hebrew texts from his early years in Lithuania and Brooklyn.

Much of the work between these two periods illustrates Shahn’s range as an artist and documentarian. He often worked from reference photographs and newspaper photos, many of which are included in the exhibition alongside the final artworks. All told, the show brings together 175 pieces, including paintings and watercolors, preparatory studies, prints, photographs, and commercial designs, highlighting the fluidity of the artist’s style, mastery of various mediums, and adherence to the show’s throughline: Shahn’s guiding principle of nonconformity.

This was, he said, the only way forward for artistic innovation and positive societal change.

—Katy Kiick Condon

Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity • Jewish Museum, New York• May 23 to October 12 • thejewishmuseum.org