When collectors of early nineteenth-century American folk portraits get together, the discussion often includes someone asking, “Hey, did you ever see that wonderful painting we found hidden away in this little-known museum?” America is filled with local history museums, town libraries, and regional art museums containing some of the finest examples of early American portraiture.

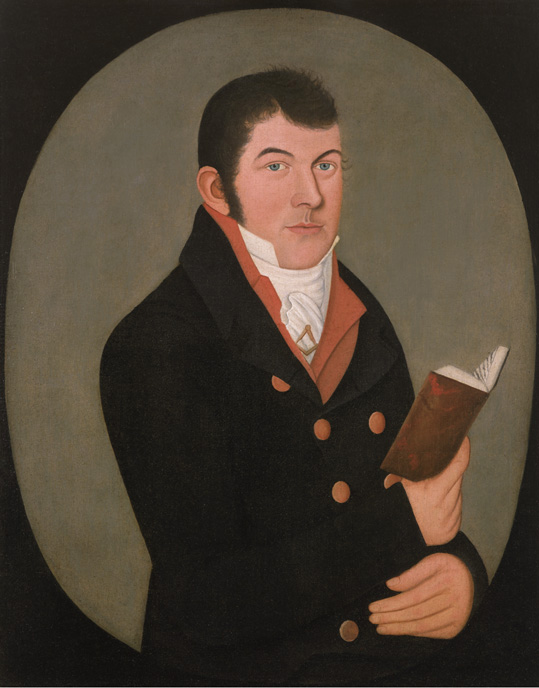

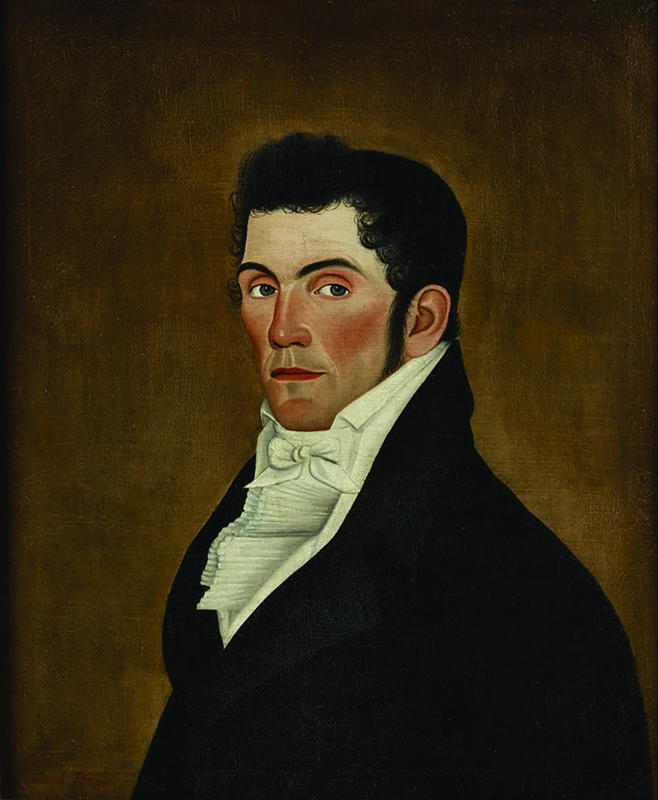

The Sterling Historical Society in Sterling, Massachusetts, is one of the museums that is often mentioned. Located in a historic Federal house and filled with objects of the town’s history, the museum is run by volunteers and is only open for three hours per week on Tuesday mornings. Displayed on the second floor are portraits by the so-called Burpee-Conant limner, an artist whose actual name had been forgotten. The pseudonym is derived from four portraits, showing two sisters, Relief and Sophia Burpee, who married two brothers, Jacob and Samuel Conant (Figs. 1a, 1b, 2a, 2b). Three of the portraits remain in Sterling, where they were painted, while the fourth, of Sophia Burpee, is in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC. The portraits of Samuel and Sophia were probably painted at the time of their November 1813 wedding. He is holding roses, a symbol of love and an unusual feature in a man’s portrait at this time, that complement the white roses in his bride’s hair. Relief and Jacob had married three years earlier in 1810, yet both the brides and husbands are wearing similar clothing and are seated on almost identical chairs. These similarities reinforce the close relationship between the two couples and suggest that all four portraits were painted at the same time. Both Sophia and Relief died in late 1814, likely victims of a typhoid epidemic that swept through the town, so 1813 or 1814 is assumed to be when the portraits were painted.

We have located portraits that can be attributed to the Burpee-Conant limner that are signed by John Tolman. However, there were dozens of men with this common name, which made it quite difficult to correctly identify which of them was the artist. Fortunately, the 1918 revised and enlarged edition of William Dunlap’s important History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States mentions Tolman, noting that he “painted in Boston and in Salem, Mass, about 1816 and evidently travelled over the entire country as a portrait painter. His home was in Pembroke, Mass.”

Even so, during the first half of the nineteenth century, three men named John Tolman were associated with the small town of Pembroke: an older shipbuilder and seaman who died in 1831, a date after which the artist was still actively painting; the artist; and the artist’s son, who was born in 1807. Not unexpectedly, over the years, information about these three men has become intermingled, so it is necessary to clearly describe the artist. He was born in Marshfield, Massachusetts, on September 3, 1777, one of nine children of Benjamin (1742–1824) and Marcy/Mercy Thomas Tolman (1743–1835). He was living in Abington, Massachusetts, when he married Averick Everson (1782–1854) of Pembroke on October 13, 1802. That same year, he purchased a home in Pembroke with four acres of land, along with twenty-seven additional acres of farmland in Marshfield. This home would be maintained through the birth of ten children and until his death in 1863.

No specific information has been uncovered about Tolman’s artistic training, but he may have had an introduction to Boston artists through William Tolman, whose birth date suggests he was probably John Tolman’s older brother. William was a gilder and frame maker who was listed in the Boston city directories from 1805 to 1815. Local artists frequented his shop; for example, the portrait painter Ethan Allen Greenwood recorded in his account book on February 15, 1815, that he “Rec’d 7 frames from Tolman, prepared & gilt by him.”

The earliest portraits attributed to John Tolman are those of Olive and Joseph Morse, which are dated 1807 (Figs. 3a, 3b). As this is the year the Morses married, these may have been wedding portraits painted in Newbury, Massachusetts. The next likenesses we know of that are attributable to the artist are those of the Burpees and Conants, painted in 1813 or 1814 in Sterling. About the same time, Tolman painted a portrait of Horatio Gates Buttrick, signed and dated “Tolman Pinxt / 1814” (Fig. 4). During 1814 Buttrick was living either in the adjacent town of Westminster, Massachusetts, or in the Sterling home of his uncle Francis Buttrick, who was a business partner of the Conants. Francis Buttrick’s signature appears repeatedly in Conant family legal papers, either as a witness or as the town’s justice of the peace. Horatio Gates Buttrick was revered in his lifetime as the son of Major John Buttrick, one of the American militia commanders at the Battle of Concord during the Revolutionary War. Major Buttrick’s fame rests on the suggestion that it was he who ordered “the shot heard round the world,” described in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Concord Hymn.”

Sterling was an unlikely location for a large number of oil-on-canvas portraits to have been produced at the time, since it was a small agricultural community with a limited number of possible clients for an itinerant portrait painter. Tolman’s mother was born in Sterling and he was probably visiting Moses and Rebecca Thomas, his maternal uncle and aunt, who were still Sterling residents.

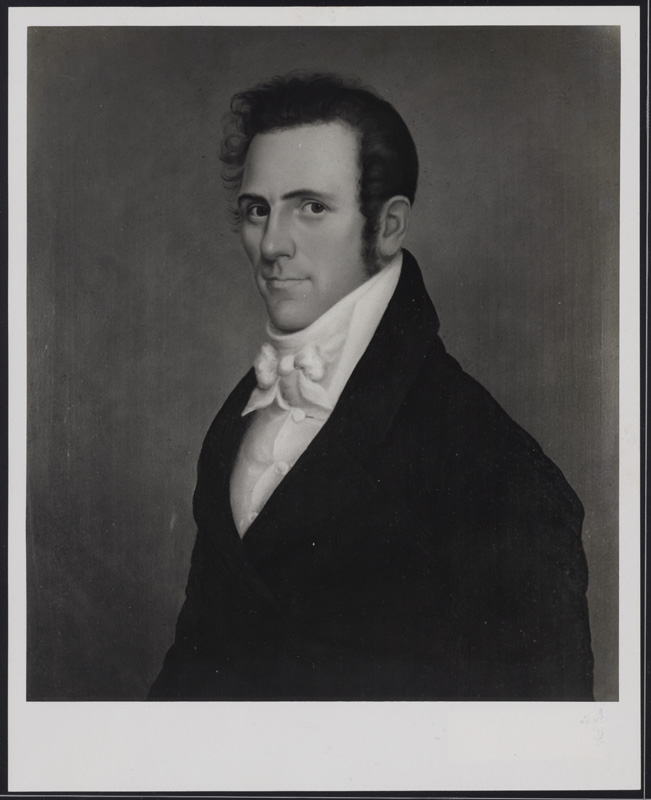

His portraits are often found in pairs depicting a husband and wife. Older sitters generally wear austere dress that is plainer, less colorful, and with few adornments in comparison to that of younger sitters’ highly decorative clothing (Figs. 5, 6). Portraits of children seem to have been painted on smaller canvases than adult portraits (Fig. 8). A comparison of the faces from several portraits with the signed image of Horatio Gates Buttrick reveals that they were painted by the same artist (Figs. 7a, 7b, 7c).

The power of Tolman’s paintings is derived from their striking simplicity in a reductive style that shows only what must be there. Bold, crisply defined lines create meticulously outlined shapes that are often filled with bright coloration. Sharp lines surrounding the figure flatten the image, so that the sitter appears to be seated right at the edge of the canvas. Everything is focused on the sitter, who communicates directly with the viewer, almost staring back. The backgrounds are empty and undefined, in contrast to the often colorful and visually heightened image of the sitter. Occasionally, drapery above the sitter is used to create a more formal presentation. The unusually bright light that falls directly on each sitter seems to come from the viewer’s world, not from the world of the portrait. Almost all chiaroscuro, the tonal contrasts of light expected to be seen as the effect of the sitter’s volume, and almost all shadows, have been eliminated. The strength of the image makes the sitter’s high social status seem obvious.

The sitter’s body is most often presented with a quarter-turn to the viewer. This distorts the torso into a side view that either eliminates or minimizes one arm, while the face is further angled toward the viewer. Some of the portraits demonstrate a distinctively awkward linear perspective so that the figure sits solidly, but stiffly. The sitter’s face is lightly modeled with facial creases and the skin tonality predominating, the nose is highlighted by a sharp shadow, and a single dramatic line defines the inner lips, with shaded creases extending down from the corners of the mouth. Hair is usually painted in great detail: soft ringlets for the women, while some of the men show a style popular at the time with strands of the hair brushed forward. Other characteristics are the way eyelids are painted, and the D-shape construction and darker color of the inner ear auricle. Paint is consistently thinly applied without visible brushstrokes, except in costume details such as women’s laces and men’s jabots, which often have a slight impasto to suggest volume.

The early 1800s was a difficult economic time for a portrait painter. Beginning in 1807, Thomas Jefferson’s embargo prohibited the import or export of goods and greatly damaged the American economy. The War of 1812, which lasted to 1815, also affected every American life. Then, the Panic of 1819 resulted in a depression that produced a general economic collapse that lasted, in several regions of the country, into the mid-1820s. Portrait painters traveled constantly to seek sitters who had both the desire and affluence to commission their work. Tolman joined the many itinerants on the road.

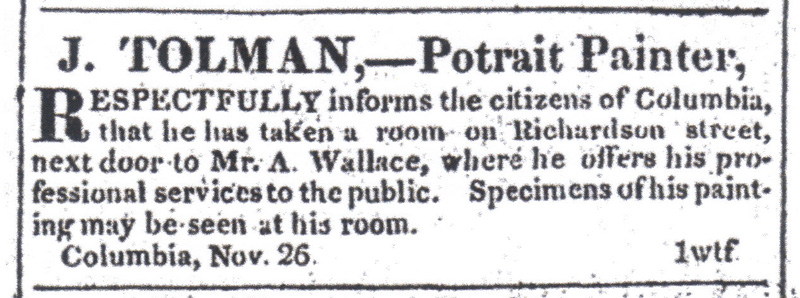

We have located thirty-four newspaper advertisements, published between 1815 and 1835, that allow us to follow Tolman’s travels. When arriving in a new locale, he ran newspaper advertisements stating that he had rented a prominent space where specimens of his work were displayed. The earliest advertisement that has been located appeared in the October and November 1815 issues of the Merrimack Intelligencer of Haverhill, Massachusetts. It announced that Tolman “has taken a room over the bank in Haverhill, for a few days; and solicits the patronage of the public.” The portrait of Ladd Haselton of Haverhill signed and dated October 1815 by Tolman, was painted during this visit.It displays all the characteristics of portraits ascribed to the Burpee-Conant limner.

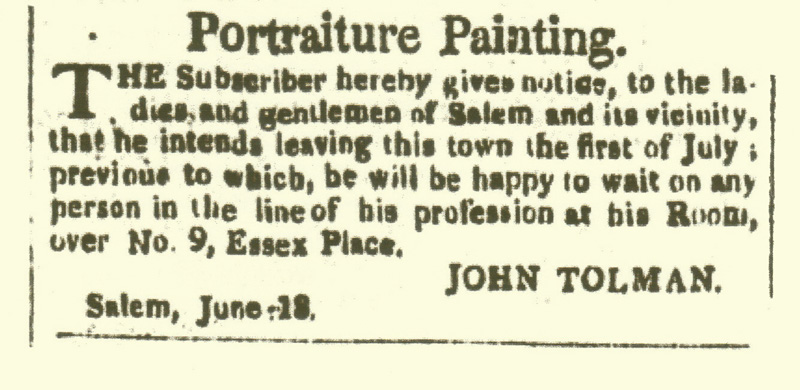

Tolman advertised in Salem, Massachusetts, on December 19, 1815; and in June 1816 he announced that “he intends leaving this town the first of July” for Boston (Fig. 10).

According to an old note accompanying Reuben Washburn’s portrait (Fig. 9), the sitter recorded in his diary on August 24, 1816, in Lynn, Massachusetts: “Paid Mr. John Tolman for taking our portraits $25.00” and “For Mr. Tolman’s board at the Hotel one week $3.00.” Apparently, in addition to the cost of the paintings, the sitters were sometimes charged for the artist’s living expenses during the time it took to produce the portraits. During October 1816 Tolman advertised that “specimens of his Painting can be seen” in New Haven, Connecticut.

Tolman’s advertisements then reveal a somewhat unusual itinerancy for a New England folk portrait painter. His hometown of Pembroke, located on the navigable portion of the North River, which empties into Massachusetts Bay, was particularly known for its shipbuilding industry and allowed for easy ocean travel along the East Coast. In November 1816 he visited Charleston, South Carolina, and placed several advertisements in the local newspapers. For the next two decades, he would routinely paint in a southern city during the winter months and then return to Pembroke and travel throughout New England for the rest of the year. This pattern provided a welcome escape to a warmer climate for the winter. It also suited his southern customers’ agrarian lifestyle, in which December through February were the more leisurely months of the year. Although several folk portrait painters are known to have traveled with their families, Tolman’s wife appears not to have accompanied him, since all of their ten children were born and raised in Pembroke.

It is possible that Tolman was following an itinerancy established by the portrait painter Cephas Thompson, who lived in Middleborough, Massachusetts, about thirteen miles from Pembroke. As early as 1808, Thompson spent the winter months in the South and then traveled through New England during the rest of the year. Thompson’s memorandum book describes his travels, and shows that the locations of his southern visits never overlapped with those in Tolman’s advertisements.

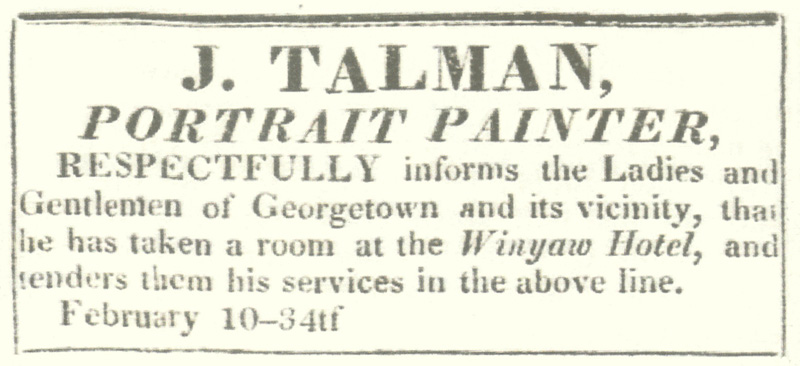

However, the major southern cities were crowded with artists. More than one hundred painters worked in Charleston between 1800 and 1825. Tolman visited Charleston at least twice, as well as other prosperous South Carolina towns such as the state capital of Columbia in 1822 (Fig. 11) as well as Georgetown, which gained its wealth from massive rice plantations. The Georgetown advertisement of February 1826 is his typical brief statement announcing that the public can be provided with a portrait and his location, but calls him J. Talman (Fig. 12).

Commissions for a newly arrived itinerant painter were difficult to obtain in a city where artists who had lived in the community for years dominated the local portrait business. Tolman often traveled to smaller towns where there may have been less competition for his services. In January 1817 he advertised in Camden, South Carolina, a small town 127 miles inland from Charleston, that “He will not receive any pay if his paintings are not done to perfect satisfaction.” During January 1820 he advertised in Savannah, Georgia, and during May 1820 in Augusta, Georgia.

In that same year Tolman’s hometown of Pembroke was divided into two townships, based on the areas served by the two Congregationalist churches. The western church, which included his home, became the town of Hanson, with a population of 917. With his active traveling, the twenty-seven acres of farmland purchased in 1802 was of little use to him, so in July 1828 Tolman sold it to his two eldest sons when the second of them reached age twenty-one.

Further information about John Tolman is presented in one of the first books written about early American folk portraiture: Some American Primitives: A Study of New England Faces and Folk Portraits by the early collector Clara Endicott Sears (1863–1960), published in 1941. Sears’s major collection of folk portraits has remained intact and can be seen today at the Fruitlands Museum, which she established in Harvard, Massachusetts. Her book is filled with interesting anecdotes about the itinerant portrait painters of the early nineteenth century and is still used as an important source of information. The lives and travels of these itinerant artists are described as one of the most picturesque phases of American life. One correspondent wrote to her: “my father was well acquainted with John Tolman . . . about eighty years ago. I learned from what he said that Tolman was an itinerant portrait painter, and self-taught artist. He traveled all over the country, practicing his profession. At one time he was stopped at a hotel in New Orleans, and the building totally collapsed while he was sleeping.”

Newspapers throughout the United States published detailed descriptions of the disaster, which occurred during the night of May 15, 1835, when the Planters’ Hotel on Canal Street suddenly collapsed into a pile of rubble. With some sixty to seventy people inside, the screams of the wounded brought out all of the city’s fire department, and “hundreds of citizens were exerting themselves to extricate the mangled and bruising bodies of the victims of this awful casuality.”With seven or eight people dead, the wounded “Mr. Talman [sic], portrait painter, had his arm greatly mashed.”

This was probably the end of Tolman’s itinerancy, as well as his painting career, as no advertisements or portraits have been located after this date. During 1839 Tolman again purchased farmland near his home, including nineteen acres in Pembroke and land in Hanson. This part of Massachusetts had become a major shoe production area and Tolman was described in later censuses, along with almost all of his neighbors, as a shoemaker. John Tolman died in Hanson at age eighty-five in 1863, the cause of death being “old age.” His probate listed $87.30 in household furniture, farm tools, and hay, $665.00 in real estate, and $258.94 due in notes held by the deceased.

It is highly gratifying to identify the Burpee-Conant limner portraits, painted some two hundred years ago, as the work of John Tolman and to describe the life of this early American artist.

1 The artist has been called variously the Burpee-Conant, Conant, and Merrimac limner. The Sterling Historical Society has two additional attributed portraits of sitters whose identities have not been confirmed. Sophia Burpee’s schoolgirl art in the historical society and elsewhere led to the incorrect conjecture that she could be the artist. 2 Deborah Chotner, American Naive Paintings (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 1992), pp. 74–77. 3 William Dunlap, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States, ed. and rev. Frank W. Bayley and Charles E. Goodspeed (Boston, MA: C. E. Goodspeed and Co., 1918), vol. 3, p. 338. That Tolman’s home was in Pembroke is described in several additional sources, including: Henry Wyckoff Belknap, Artists and Craftsmen of Essex County Massachusetts (Salem, MA: Essex Institute, 1927), p. 13; and Mantle Fielding, Dictionary of American Painters, Sculptors and Engravers, rev. ed. (Green Farms, CT: Modern Books and Crafts, 1974), p. 370. 4 An extensive examination of men named John Tolman living in New England and New York did not find another individual described

as a portrait painter. Genealogical information was obtained from

ancestry.com, familysearch.org, and thomastolmanfamily.org. The artist advertised once as John Tolman Jr., but only in his first advertisement, published in Haverhill, Massachusetts, in 1815. John Broad

Tolman (1806–1891), a Lynn, Massachusetts, merchant, and John R. Tolman have been incorrectly identified as the artist. 5 Georgia Brady Barnhill, “‘Extracts from the Journals of Ethan A. Greenwood’: Portrait Painter and Museum Proprietor,” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, vol. 103, part 1 (1993), p. 121. 6 In 1834 Buttrick became the superintendent of buildings at Hamilton College in Clinton, New York, which began a long relationship between his family and the college. His portrait remains at Hamilton College. 7 See Edwin Conant papers, 1792–1888, American Antiquarian Society, Worcester, Massachusetts. 8 Buttrick is a familiar name as a relative, Ebenezer Butterick, a tailor in Sterling, Massachusetts, in 1863 developed home sewing patterns printed on tissue paper that allow complex garments to be cut out of fabric and assembled. It is today a worldwide brand. 9 Merrimack Intelligencer (Haverhill, MA), October 14 and November 25, 1815. 10 Norman Hudson, Antiques at Auction (Cranbury, NJ: A. S. Barnes and Co., 1972), p. 354. The portrait is inscribed “Ladd Haselton, AE 24/ Painted by J. Tolman, Oct 1815” on the back. This published image is of a poor quality. 11 Belknap, Artists and Craftsmen of Essex County Massachusetts, p. 13. 12 Salem (MA) Gazette, June 18 and July 2, 1816. 13 Columbian Register (New Haven, CT), November 9, 1816. 14 Tolman advertised in both the Charleston Times and Charleston Courier during November 1816. 15 Deborah L. Sisum, “‘A Most Favorable and Striking Resemblance’: The Virginia Portraits of Cephas Thompson (1775–1856),” Journal of Early Southern Decorative Arts, vol. 23, no. 1 (Summer 1997), pp. 1–101. Thompson’s visits to the South ended in 1822, while Tolman continued to 1835. 16 Anna Wells Rutledge, “Artists in the Life of Charleston Through Colony and State from Restoration to Reconstruction,” Transactions of The American Philosophical Society, new series, vol. 39, part 2 (1949), pp. 101–260. 17 The artist’s name has been incorrectly written as Tollman, Toleman, Talman, and Tallman. 18 Camden (SC) Gazette, January 16–February 6, 1817; Columbian Museum and Savannah Daily Gazette, throughout January 1820; and Augusta Chronicle and Georgia Gazette, May 20, 1820. 19 Clara Endicott Sears, Some American Primitives: A Study of New England Faces and Folk Portraits (Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1941), p. 290. This quote appears to be from Ethel G. Tolman, who is acknowledged in the book’s foreword. 20 Baltimore Gazette and Daily Advertiser, May 29, 1835, p. 2. 21 We gratefully thank Ralph and Susanne Katz as well as Michael Heslip for the suggestion of a relationship between the Horatio Gates Buttrick portrait and the Burpee-Conant limner.

Michael R. Payne and Suzanne Rudnick Payne are collectors and members of the American Folk Art Society. This is the nineteenth article they have published about early American folk portrait painters.