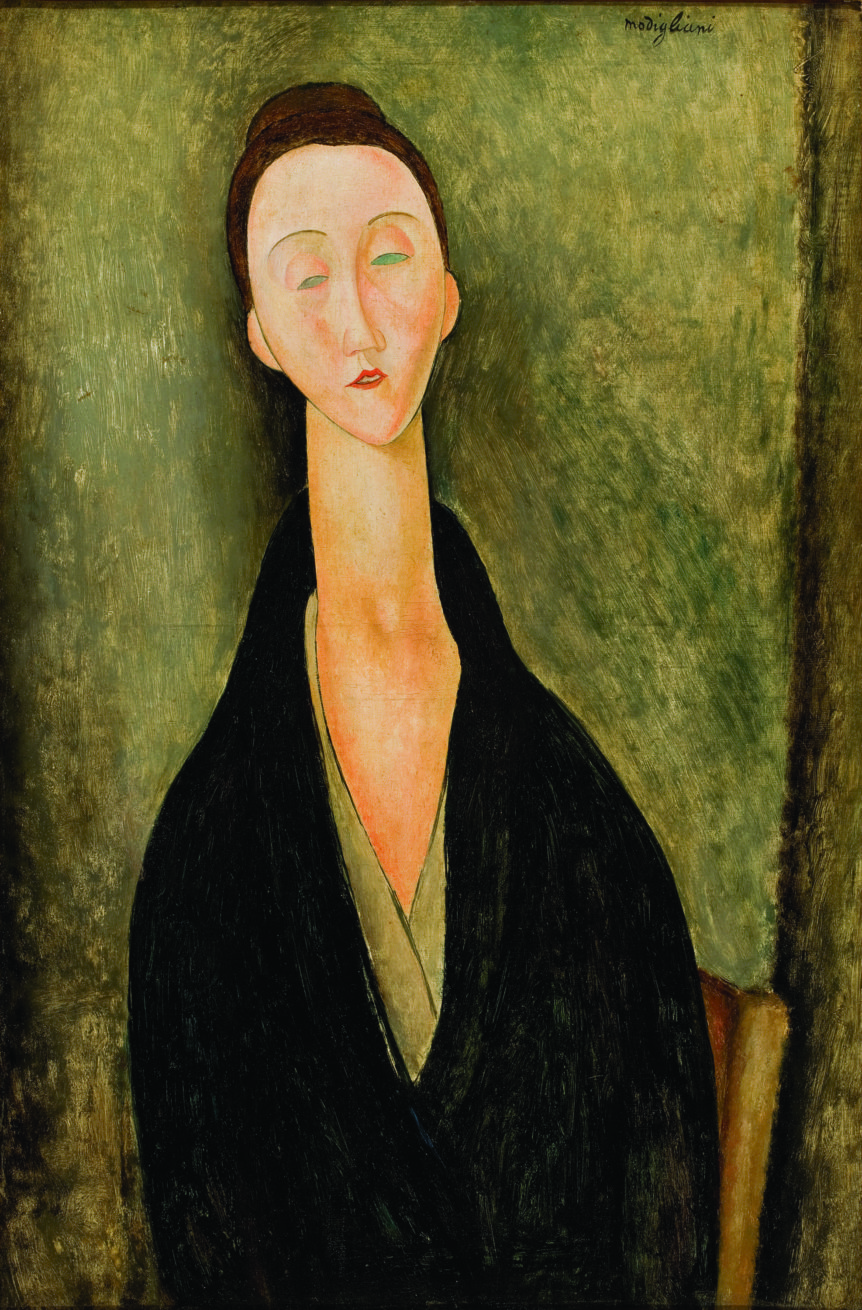

Fig. 1. Hanka Zborowski by Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920), 1916. Signed “modigliani” at upper right. Oil on canvas, 18 by 15 inches. Private collection.

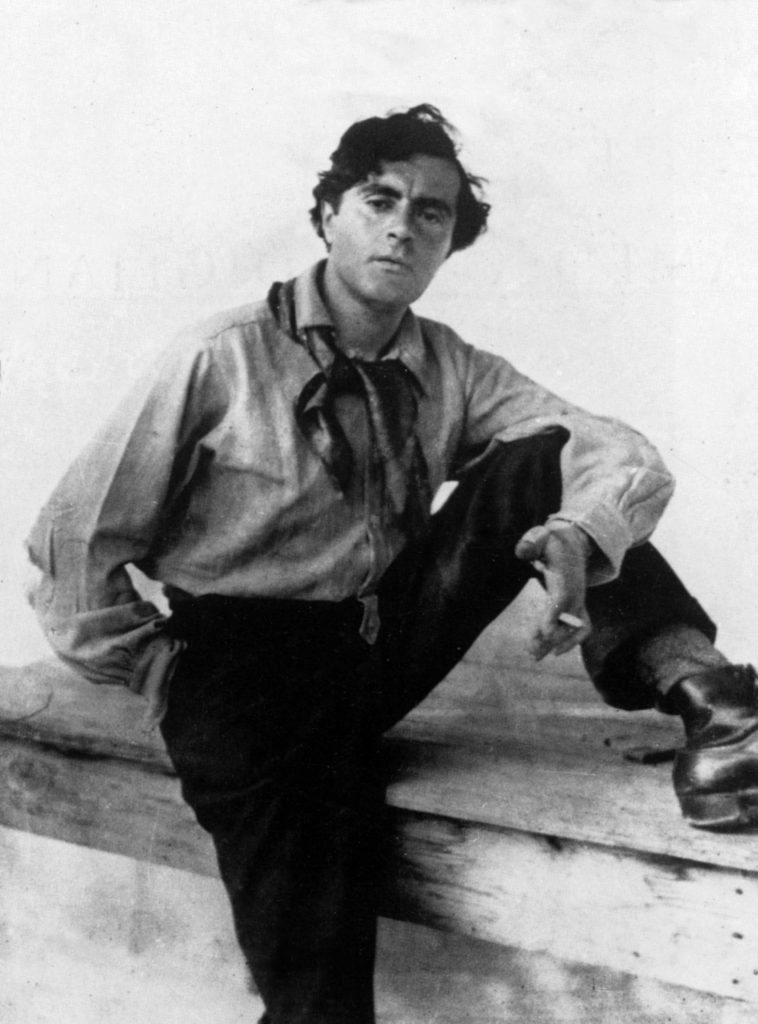

A legendary, near-mythological figure in early twentieth-century art, Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920) is perceived today as the bohemian artist par excellence. Living and working in Paris in the first decades of the twentieth century, Modigliani was supremely gifted, handsome, and charismatic. His body, though, by the time he reached his late twenties, was ravaged by the effects of tuberculosis, alcohol, and drugs. Stories of his drinking binges, hashish and cocaine use, and all-night rabble-rousing sometimes overshadow his formidable contribution to twentieth-century art.

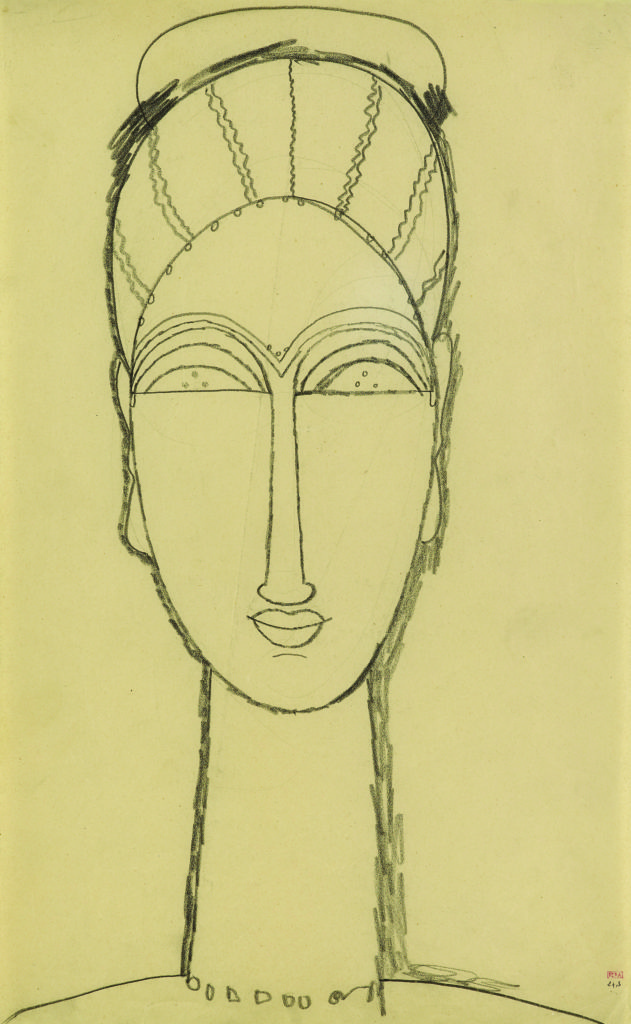

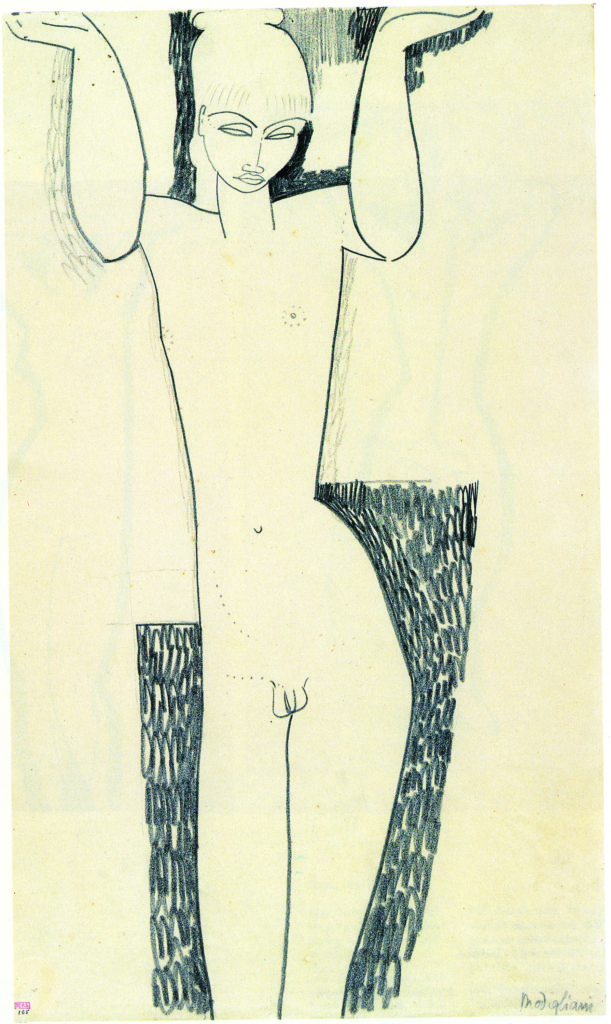

Fig. 2. Female Head, 1911–1912. Black crayon on paper, 16 ¾ by 10 3/8 inches. Courtesy of Paul Alexandre Family / Richard Nathanson, London; photograph by Prudence Cuming Associates, London.

During a career that lasted only some fourteen years, he established a considerable reputation among his peers as a painter, sculptor, and draftsman. He lived in dire poverty, although collectors, curators, dealers, and critics began to take notice of his work in the years just before his death. He was known for his idiosyncratic approach to the figure, especially portraits, which featured elongated necks, prominent noses, and “gazeless” eyes, a motif he borrowed from his hero, Paul Cézanne.1 Modigliani incorporated into his work a wide range of art-historical references, from late medieval sculpture and mannerist painting to cubism and African art. After his death at age thirty-five, he achieved a level of popular and critical acclaim that can be compared only to that of Vincent van Gogh, and more recently, Jean-Michel Basquiat, whose stars burned so brightly—and briefly.

Fig. 3. Amedeo Modigliani, c. 1912. PVDE /Bridgeman Images, New York.

Modigliani surveys are rare in the United States, and the Jewish Museum’s Modigliani Unmasked is an especially ambitious attempt to separate artist from legend, fact from fabrication, by means of an in-depth examination of the artist’s works on paper. The show was organized by Mason Klein, the museum’s curator responsible for its 2004 blockbuster Modigliani: Beyond the Myth. The present exhibition contains about 125 drawings, twelve paintings, and seven sculptures by the artist, including the only 3-D version he ever produced of his beloved Caryatid theme. Also on view are a number of examples of the ancient Cycladic, Egyptian, African, and Asian artworks that inspired Modigliani. The bulk of the drawings, many never before shown in the United States, were loaned by the family of Paul Alexandre (1881–1968), a doctor and collector who was Modigliani’s close friend and early patron from 1907 until 1914. (Alexandre lost touch with the artist during World War I, when he served as a medical officer on the Western front.) Modigliani Unmasked considers the drawings as key to the artist’s lifelong exploration of his own identity as an outsider—an Italian Jew living in the anti-Semitic environment of Paris in the years following the infamous Dreyfus Affair.

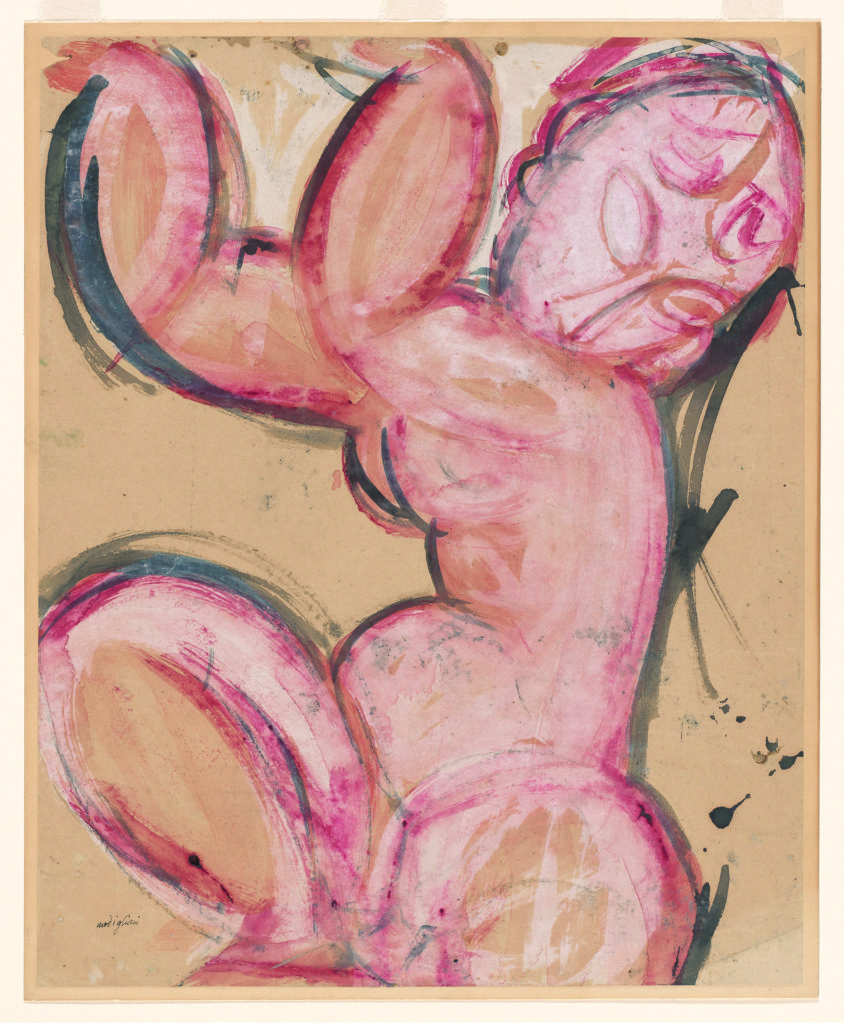

Fig. 4. Caryatid, 1914. Signed “modigliani” at lower left. Gouache and ink on paper, 22 ¾ by 18 ½ inches. Museum of Modern Art, New York, bequest of Mrs. Harriet H. Jones, licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, New York.

Born in Livorno, Italy, to parents who were prominent members of the local Sephardic Jewish community, Modigliani also had French ancestors who claimed to be descendants of the philosopher Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677). A sickly child who suffered from recurring chest ailments, Modigliani grew up in a cultured environment, appreciative of art, music, and literature. He learned French at an early age and took an interest in drawing. Eventually, he studied art in Florence and at the Royal Institute of Fine Arts in Venice. But Paris, the center of the art world, beckoned, and in 1906 he relocated there, eventually settling in the émigré community of avant-garde artists in Montparnasse.

Fig. 5. Caryatid, c. 1914. Limestone; height 36 ¼ inches. Museum of Modern Art, New York; Mrs. Simon Guggenheim Fund, licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, New York.

Modigliani was proud of his Italian roots and Jewish heritage. “He never experienced anti-Semitism until he arrived in Paris,” says Klein.2 “He would often introduce himself, giving his name and hastily adding, ‘Je suis Juif (I am Jewish).’” The comment was something of a provocation in France at that time. Captain Alfred Dreyfus—the Jewish artillery officer convicted of military espionage on the basis of a false document—was finally exonerated the year Modigliani came to Paris. The poisonous, polarizing atmosphere surrounding the scandal lingered heavily.

Fig. 6. Adrienne, c. 1909. Blue ink on paper, 10 5/8 by 8 ¼ inches. Private collection, courtesy Richard Nathanson, London; Prudence Cuming Associates photograph.

That Modigliani explored his identity as an Italian expatriate Jewish outsider through his art, especially in his drawings, is the central premise of Modigliani Unmasked. Drawings, in fact, were his bread and butter, in a quite literal sense. He would hawk them for food and drinks in the cafés and bistros of Montmartre and Montparnasse. His favored subjects were his friends, including Paul Alexandre, Pablo Picasso, Max Jacob, Chaim Soutine, Jacques Lipchitz, and Jean Cocteau, among others. Female nudes and his majestic Caryatids are also frequent drawing subjects.

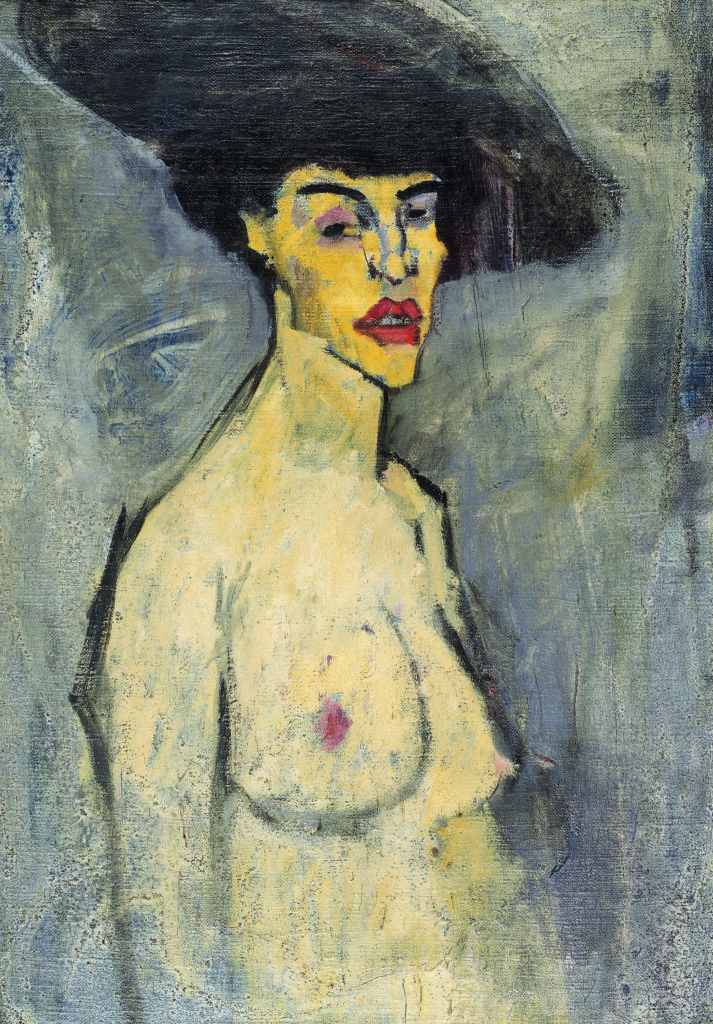

Fig. 7. Nude with a Hat, 1908. Oil on canvas, 31 7/8 by 21 ¼ inches. Reuben and Edith Hecht Museum, University of Haifa, Israel.

The graceful and energetic lines in each of these works demonstrate a sense of fortitude and clarity of vision that belies certain popular misconceptions of the artist as an inebriated genius at work. In the 1958 biography of her father, Modigliani: Man and Myth, Jeanne Modigliani noted that the artist’s contemporaries she interviewed for the book stated that they “never saw Modigliani or any other artists paint or draw while under their [drugs and alcohol] influence. However full of genius their visions then may have been, their real creative work could be done only when their heads had cleared.”3

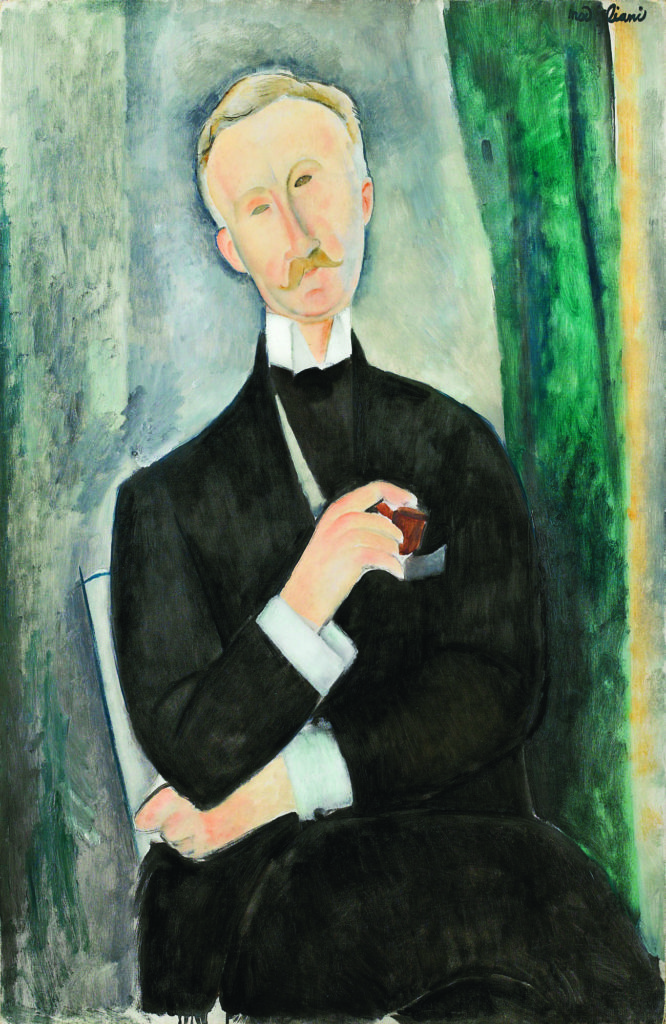

Fig. 8. Portrait of Roger Dutilleul, 1919. Signed “modigliani” at upper right. Oil on canvas, 39 ½ by 25 ½ inches. Collection of Bruce and Robbi Toll.

Many of the drawings feature schematic renderings of heads. These well-known images relate to the sculptures that preoccupied Modigliani between 1909 and 1914, when he worked closely with Constantin Brancusi, and studied works of tribal art at Paris’s Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro.

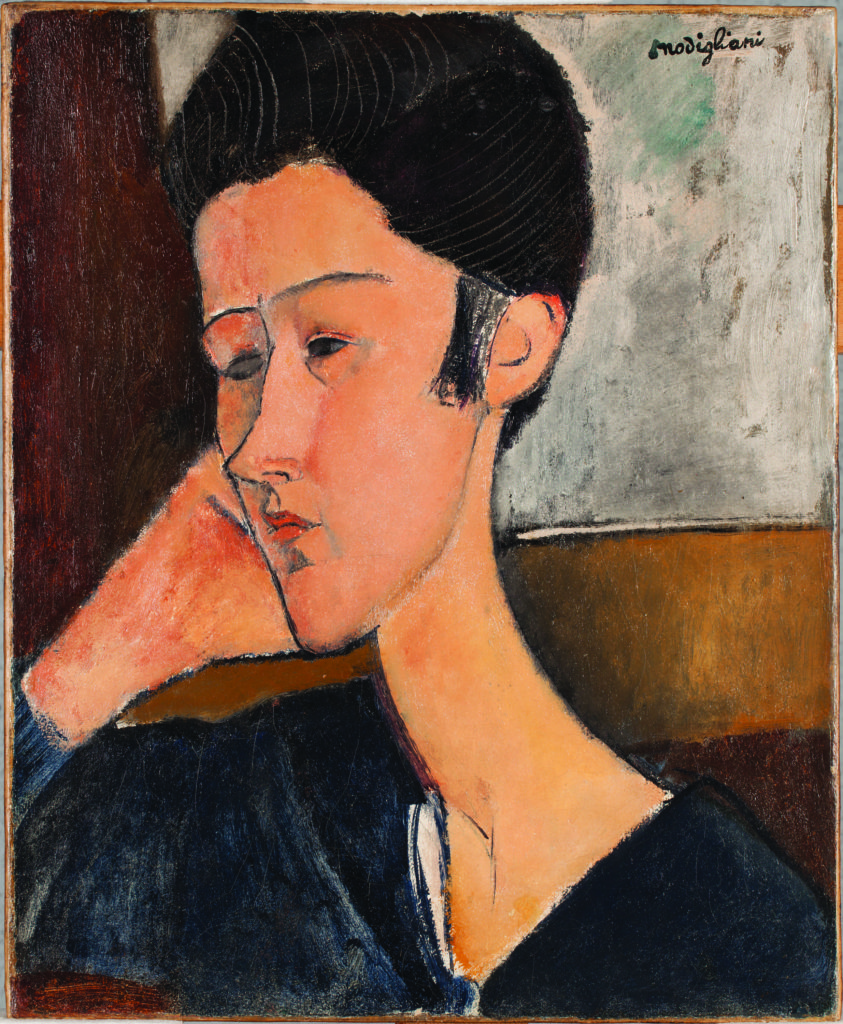

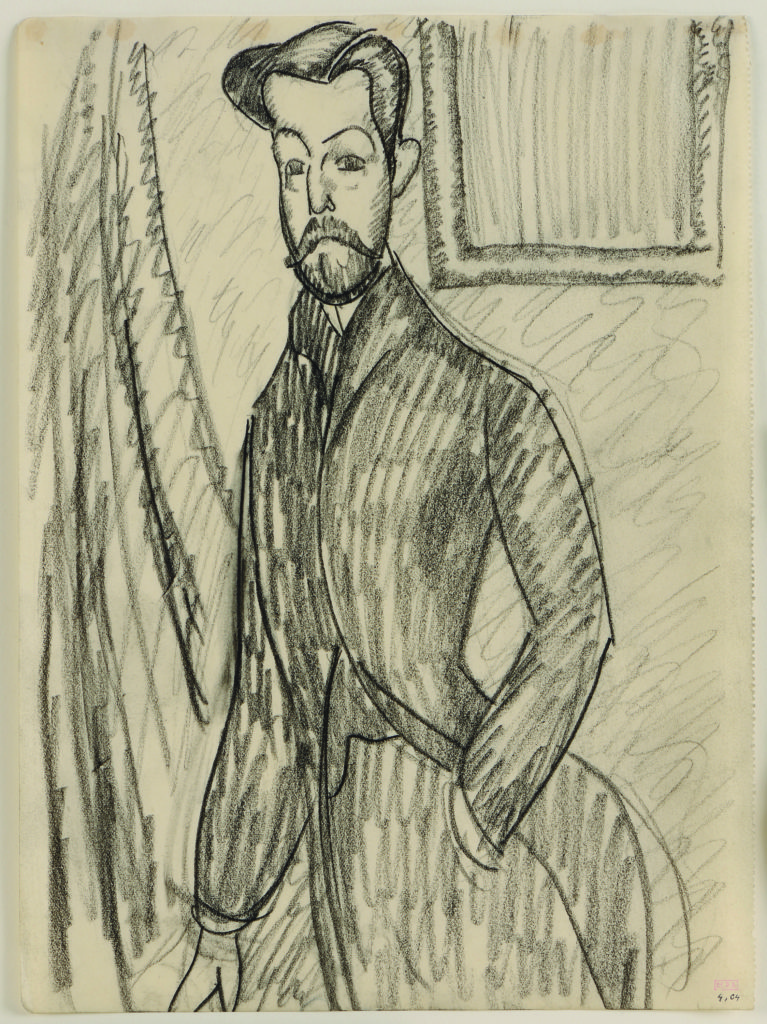

Fig. 9. Paul Alexandre with Left Hand in His Pocket, c. 1909. Black crayon on paper, 10 5/8 by 7 ¾ inches. Laure Denier Collection, courtesy of Paul Alexandre Family / Richard Nathanson, London; Prudence Cuming Associates photograph.

A series of self-portraits is especially poignant, including the now-lost Self-Portrait with Beard (1910), represented in the show by a photograph. In this important work, the artist shows himself in a beard and tunic, among other indications of “Jewishness” that were in circulation at the time.

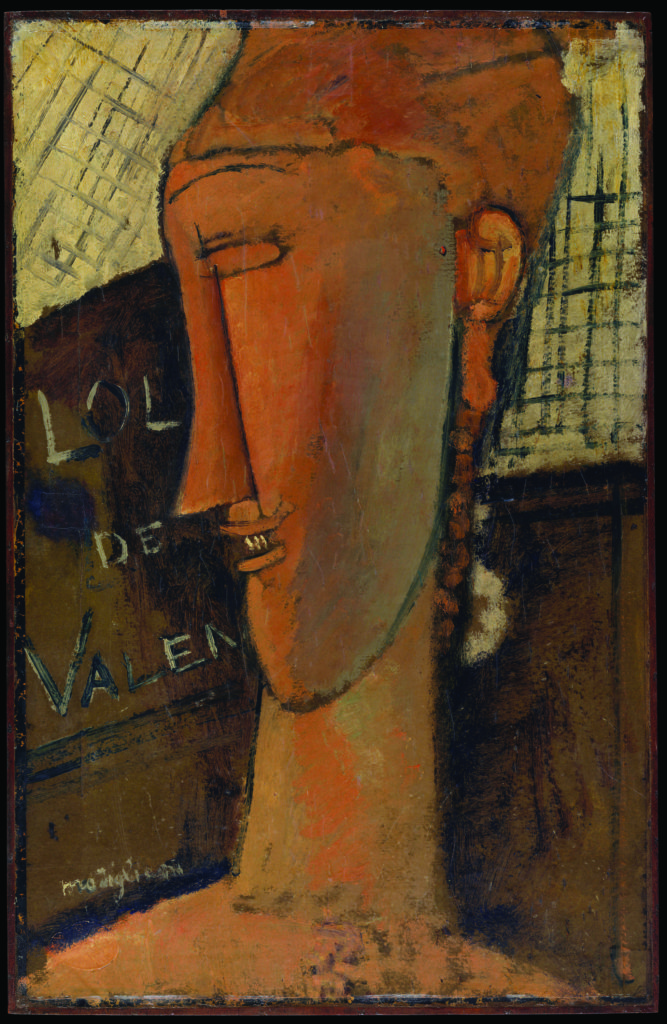

Fig. 10. Lola de Valence, 1915. Signed “modigliani” at lower left. Oil on paper, mounted on wood, 20 ½ by 13 ¼ inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art / Art Resource, New York.

“The drawings of heads and the caryatid drawings are all in various respects concerned with issues of identity,” Klein proposes. “In his study of non-Western art, Cycladic art, African, and Asian art, Modigliani was exploring his own otherness and difference in a very profound way. In many of the drawings, he is dealing with ethnicity. There was a fascination with physiognomy in Europe at the time. That is the reason why the nose is so prominent in these images; you have to consider how the nose was being caricatured everywhere at the time.”

Fig. 11. Hermaphrodite Caryatid, 1911–1912. Signed “Modigliani” at lower right. Black crayon on paper, 16 ⅞ by 10 inches. Courtesy of Paul Alexandre Family / Richard Nathanson, London; Prudence Cuming Associates photograph.

Modigliani’s work is not revolutionary in a technical sense. He did not fully delve into cubism or abstraction, for instance. Nevertheless, his art is radical in a unique way—obsessive and extreme, qualities that are especially evident in the drawings. Though his approach was in step with modernist experimentation, Modigliani sought to preserve and expound upon traditions of the figure throughout art history rather than destroy and replace those tenets.

“He was always working in one of two ways,” Klein notes. “He could be very methodical, and drew in architectonic and sculptural modes. Or he could be spontaneous, which gives the drawings a modern feel.”

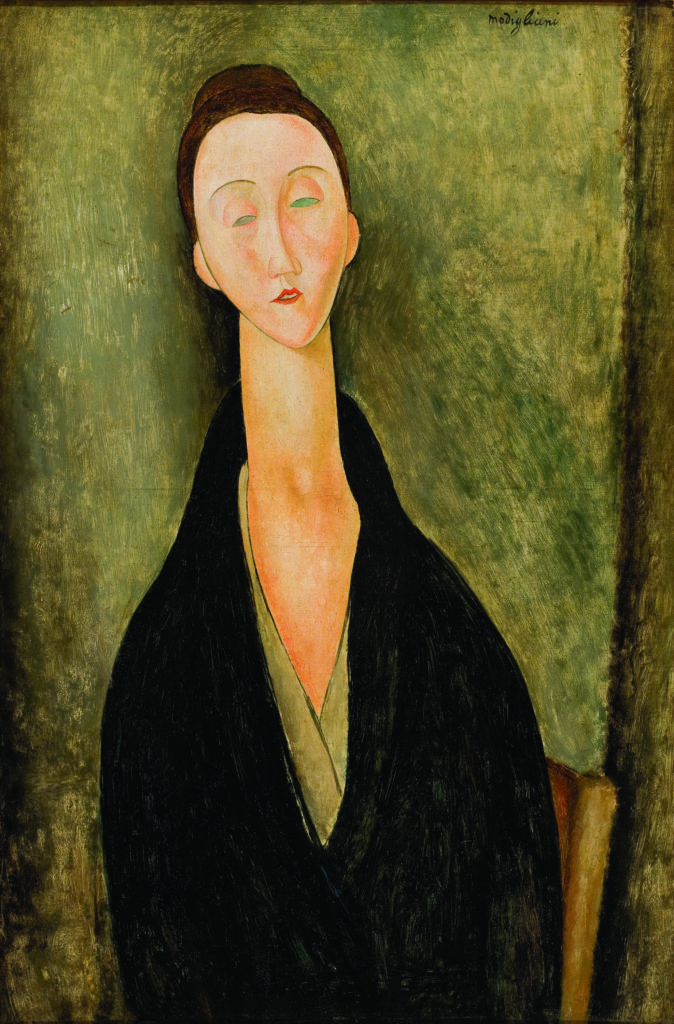

Fig. 12. Lunia Czechowska, 1919. Signed “modigliani” at upper right. Oil on canvas, 31 ½ by 20 ½ inches. Museu de Arte de São Paulo, Brazil; photograph by João Musa.

In the first group would be the art deco–like images, the Caryatids that transcend the exoticized and eroticized primitivism in vogue at the time in Paris. Each of these isolated, mostly nude, female figures holding up an unseen lintel, or the roof of a building, refer in a very specific way to architectural forms, especially ancient architecture. In the context of Modigliani’s exploration of identity, however, these images also serve as ciphers of oppression, or rather, the ability to withstand forces of oppression and bigotry. Beyond their architectonic function, they are uplifting in a spiritual sense. All of Modigliani’s works bear this universal quality, which may be regarded as a gesture of inclusiveness and compassion.

Modigliani Unmasked is on view at the Jewish Museum in New York until February 4, 2018.

DAVID EBONY is a contributing editor at Art in America and the author of a monthly column for the Yale University Press Blog, as well as a frequent contributor to Artnet News. He is also an independent curator, most recently of Grasshopper, a Judy Pfaff survey, at the Frank Institute at CR10, Linlithgo, New York, in 2016.

1 According to his friend Chaim Soutine, Modigliani said that “Cézanne’s faces, like the beautiful statues of antiquity, have no gaze . . . express nothing more than a mute concord with life.” See Werner Schmalenbach, Modigliani: Paintings, Sculptures, Drawings (Prestel, New York, 2005), p. 27. 2 This and other remarks by Mason Klein excerpted from a telephone interview with the author, July 12, 2017. 3 Jeanne Modigliani, Modigliani: Man and Myth (Orion Press, New York, 1958), p. 43.