from The Magazine ANTIQUES, July/August 2012 |

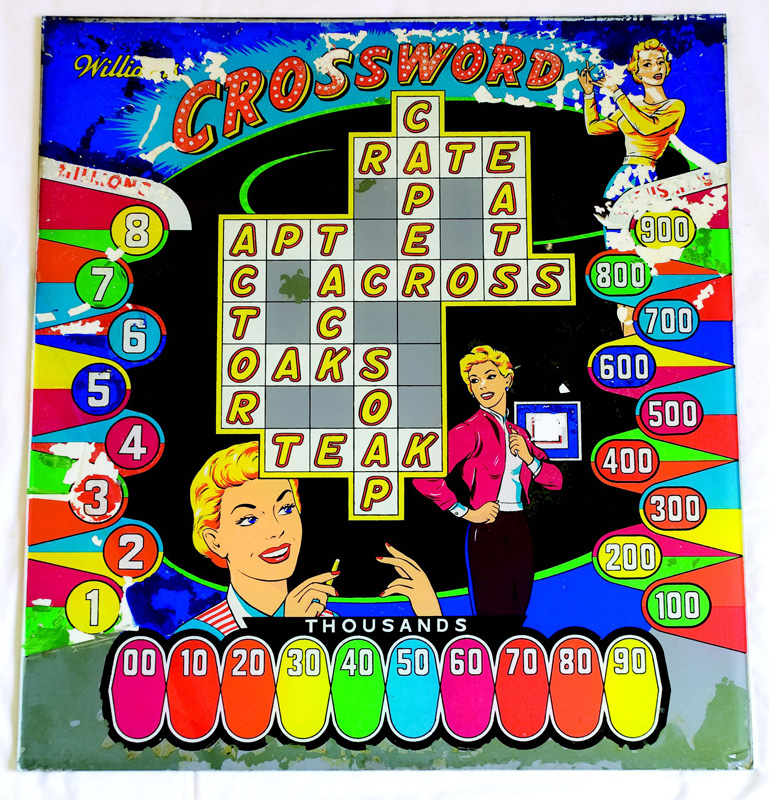

So much came to an end in 1929. The stock market crashed; the jazz age faded; Leon Trotsky was deported from the Soviet Union. Far less momentous, except to hard-core puzzle aficionados, was the one-line obituary that appeared in late December, in a New York Times book review: “The cross-word puzzle, it would seem, has gone the way of all fads.”

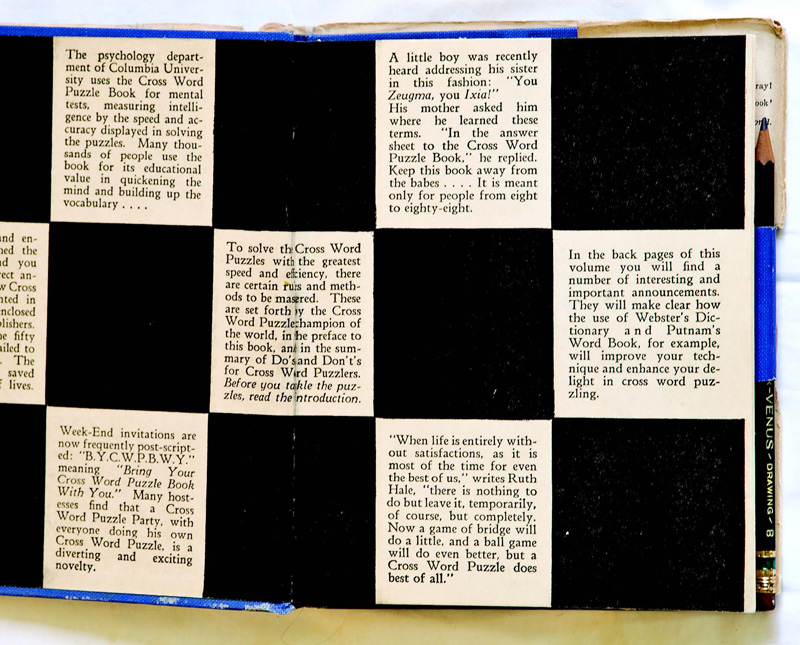

As it happens, 1929 was also the year when a handsome Tudor-style house was built in a village about thirty miles north of the New York Times offices. When the current owner bought it two decades ago, what sealed the deal was not the house’s artistry, not the woodwork, not the layout, but a tiny detail in the bathroom: a narrow strip of black-and-white checked tiles that look like squares in a crossword. Even now, Will Shortz, NPR’s puzzle master and the crossword editor of the New York Times (which finally began publishing crosswords in 1942 and is now a premiere destination for puzzle fans worldwide), beams at the tiles like a father looking at his newborn baby.

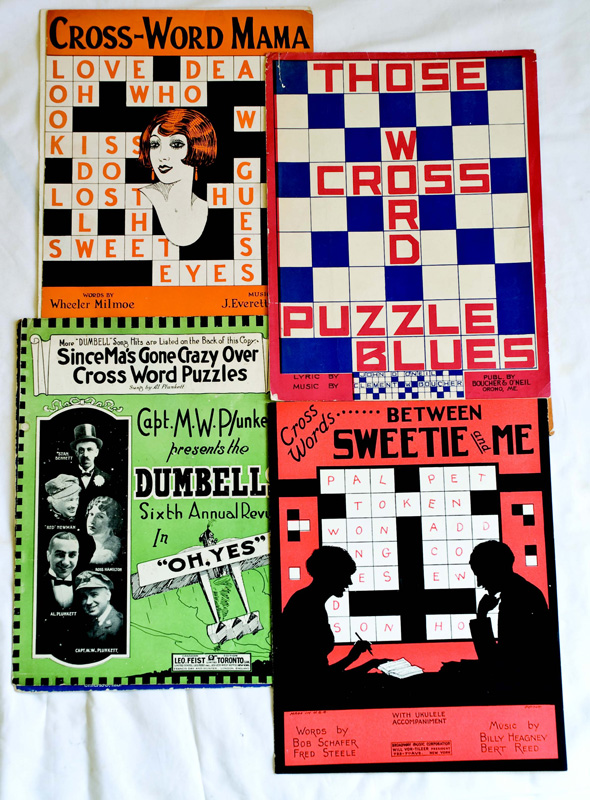

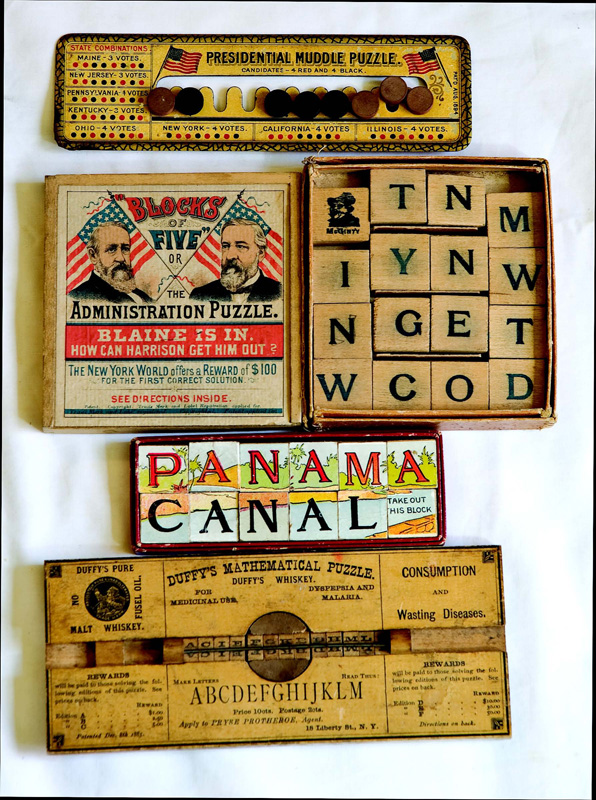

Shortz inhabits, challenges, rejoices in, and expands the universe of puzzles, from the simple-to-solve to the dazzling and all-but-undoable, from the clever to the mind-boggling. He celebrates ingenuity and his taste is catholic: he likes puzzles that involve words or numbers or pictures, and he likes unusual items-sheet music, buckets, postcards, plates-that make reference to them. (In addition, he is a demon, even fanatical, table tennis athlete, who has played in clubs in thirty-nine of the fifty states and in nineteen other countries. He owns the Westchester Table Tennis Center, which bears the slogan “Fitness for the body and mind.”) No one who has spent any time with Shortz would expect to find him playing something mindless.

He is also a world-class collector of puzzles and anything written about them, including twenty-five thousand books and magazines, in numerous languages. Many are neatly shelved in bookcases that line a former bedroom that he redesigned as a space for much of his collection. Cabinet doors open to reveal drawers overflowing with small puzzles. Two closets don’t quite edge into Collyer Brothers territory, but they’re crammed with canting stacks of magazines. There’s also the occasional cardboard box overflowing with puzzles. The area may look a little chaotic, but this is chaos of a highly controlled kind. Shortz has a rule: “Can I put my hands on it in sixty seconds?” So far, so good: he has always found what he was looking for in less than a minute. It takes less than three seconds for him to latch onto the thing that means the most to him: a stout bound volume of the collected issues of The Ardmore Puzzler, published between 1899 and 1909. Why is this so meaningful? “It was the only weekly puzzle journal ever published,” Shortz says, “and it had the cream of the work of puzzle makers of the era. It was founded and edited by ‘Remardo,’ which is an anagram of Ardmore, who was a revered puzzler.” He almost sighs as he reshelves the book. “There are a number of reasons for collecting,” Shortz says. “One, it’s practical: I’m a puzzle maker and editor and I get great ideas from these things. The more I read, the more I know. Two, there are treasures that should be preserved for future generations. And three, I just enjoy them.” Shortz has the enthusiasm of an eight-year-old and the acumen of a scholar-an ideal combination for a collector-and to understand his infectious passion for puzzles, you need to know its roots.

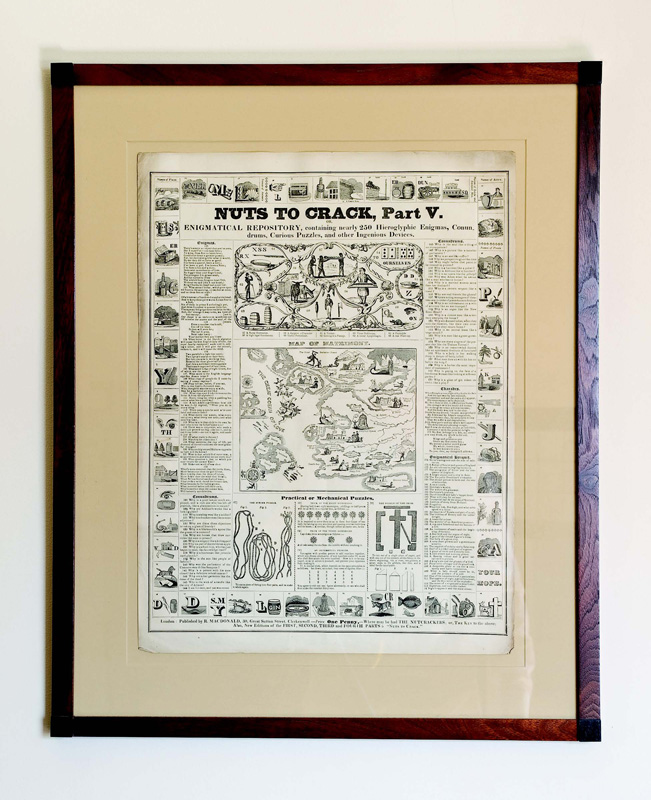

He grew up in Crawfordsville, Indiana, in a family with zero interest in puzzles. “I picked it up on my own,” he says. Even then, all kinds appealed to him, and his lifelong interest in offbeat ones began. As a boy, he spent hours in the Wabash College library, consulting The Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature for anything puzzle-related. Other kids of the time may have revered Sandy Koufax, Bill Russell, or John Glenn, but his hero was Sam Loyd. Shortz discovered him through Dover Books, which published (and continues to do so) collections of that brilliant, prolific creator of puzzles who was syndicated in newspapers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. “Loyd did logic, numbers, words,” Shortz says, “but what I especially like are the original ideas that he would dress up in fun. He’d lure you in, but he was a really tough nut to crack.”

In junior high, Shortz announced his career plan, professional puzzle maker, which must have been considered folly of the highest order, even by experts. “I was entranced by puzzles and imagined a life in them,” he says, and at fourteen he wrote to the author of Language on Vacation-“a seminal book on wordplay,” Shortz says-and told him about his ambitions. “He sent me a three-page letter that essentially said, ‘Don’t do it, kid.’” That was no deterrent, especially since Shortz published his first puzzle the same year. He also had the good luck to go to college in the early days of the independent study movement. At Indiana University, he switched from economics to a self-designed, sui generis major, and became the first-ever holder of a degree in enigmatology. (His thesis was on the history of American word puzzles before 1860.)

His parents still didn’t believe he could support himself in the field, and urged him to go into something more secure. Shortz, puzzle mania undiminished, enrolled at the University of Virginia School of Law. He had been buying books of and about puzzles for some time, and in his final semester at UVA there was a contest that interested him: write an essay, with a bibliography, about why you collect books. “One prize was for the most unusual,” he says. “I didn’t win, but the competition got me thinking that I was a collector. That was when I realized it.” He got his law degree, but bypassed the bar and immediately went to work at a puzzle magazine. The following year he got a coveted job at Games magazine, eventually becoming the editor, and stayed until joining the Times in 1993, where he has both revivified and transformed the puzzle page. Asked if he plans to retire from that job (he turns sixty in August), he looks aghast. His reply will lighten the hearts of legions of puzzle fans: “Why would I do that?”

These jobs have helped make it possible for Shortz to amass his formidable collection, but some of his prizes cost little or no money and their acquisitions come with good stories. One of the best involves what is believed to be the first published crossword puzzle, which the New York World ran on December 21, 1913. When the New-York Historical Society deaccessioned its bound volumes of the newspaper, which folded in 1931, a dealer got the rights to remove the Sunday comics, but allergies made it impossible for him to go through the volumes in the warehouse. Shortz offered to do it, at no charge, if he could have the paper’s “Fun” sections of games and puzzles, including the immortal introductory crossword. “I got it for free!” Shortz says, still luxuriating in the coup.

Shortz stumbled on to one of his favorite areas of puzzledom in the mid-1980s, when he and a friend went to a small fair. “I was astonished to learn that there were puzzle trade cards, with a puzzle on one side and an ad on the other; you’d find them on the counter when you went into a store. A puzzle is something you can spend a lot of time with, so it was good for the advertisers. I wanted to spend all day at that fair, looking in every booth and every box.” He now has binder after binder filled with trade cards, which disappeared at the end of the nineteenth century, when newspaper advertising began booming. “They’re beautiful,” he says. “They’re little works of art. They lead you into so many other worlds. I know so much about culture and history from them, from the advertising, that I wouldn’t otherwise.”

He is in the midst of his collection almost all the time, for though he has an office at the Times, he almost never uses it. Instead, he works in a small office at home. As audiences for Wordplay (the acclaimed 2006 documentary about Shortz and his work, including his American Crossword Puzzle Tournament) know, one of his greatest fans is Bill Clinton. Hanging on the wall outside Shortz’s office, where almost no one will see it, is a framed handwritten letter from the former president, who sent it on the occasion of Shortz’s fiftieth birthday. A less modest person would have placed such a trophy in a more public place, such as the living room, but that’s not in the nature of the genial, low-key Shortz. The living room is, in fact, where he displays most of the things that are dearest to his heart, in a beautiful old Gustav Stickley cabinet. They include a silver and enamel crossword bracelet from the height of the crossword puzzle boom in the 1920s, which Shortz found years ago on eBay; a unique sliding-block football puzzle; and an entire shelf dedicated to Sam Loyd, who remains his hero. “Some day I will write a book about him. I’ve found thousands of things that no one but me knows about.” Among his Loydiana are some of the inventive “vanishing” puzzles, in which a figure unaccountably disappears when you move just one small part. More than a century after their creation they remain so bewitching that they are still produced and can be bought online.

Despite these fabulous items of the past, Shortz believes that “we’re living in a golden age of puzzles. Crosswords have never been more interesting than they are now. Grids are more expertly made, clues are more ingenious. I’ve seen new mechanical puzzles that would knock your socks off.” His collecting days are not over, and never will be, but he has slowed down. “It’s hard to find things I don’t have,” he says, “but I’m always interested in new ideas and some antique puzzles have incredible ideas that have been lost.” There is still one thing he lusts for: seventeen very old missing issues of The Enigma (formerly The Eastern Enigma), which has been published since 1883 by what is now known as the National Puzzlers’ League. In 1966 someone sold a complete set of the magazines to that point, but no one knows where the issues ended up. “I believe they’re out there,” Shortz says. “For me, that’s the Holy Grail.”

When he adds anything to his collection, he still gets a little frisson. Rare book shops in other countries remain a resource for him. “Every once in a while a new world of puzzles opens up to me, like Russia,” he says. From a book dealer there, he recently got “a cool thing, a little booklet on cheap, rough paper. It’s just sixteen pages of puzzles from Leningrad in 1943 to 1944, during the siege, and it was passed from soldier to soldier.” Shortz doesn’t read Russian, and has no idea if the puzzles themselves are good. What matters to him is simply their existence, “the idea that puzzles are so powerful, even at a time like that-or especially at a time like that-that they can focus your mind and take you away from your troubles.”