Genius, William Blake informs us, always transcends its age. The same, however, cannot be said of madness, which, with a consistency rarely perceived, tends to honor the cultural norms in which it occurs. Certainly a lunatic’s behavior may challenge social convention, but, assuming he is a painter or a poet, he will largely adhere to the form and language of his age, even as he takes liberties with them. Which brings us back to Blake, a poet and a painter, and the subject of a show at the Morgan Library and Museum, first presented in 2009, that is now online thanks to the institution’s robust program for digitizing past exhibitions. In addition to a display of the poet’s manuscripts, most of the art in the Morgan show consists of Blake’s far more personal and idiosyncratic illustrations to his own poems.

Any confidence we have regarding the rightness of Blake’s mind is sorely tested by his paintings and thoroughly vanquished by his poems: in his epic poem about John Milton, to cite but one example, he imagines his great predecessor descending to earth as a comet and taking up residence in Blake’s foot. He claimed once to be in daily communication with messengers from heaven; and on another occasion said he had dinner with the prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel. But if Blake were writing today, his poetry would almost surely adopt forms and language closer to, let us say, Maya Angelou, and thus it might be she rather than the Puritan bard who took up residence in Blake’s appendage. But because Blake was born in 1757 and died in 1827, his language and meter recall not only Milton, but also the hymnists Isaac Watts and Charles Wesley.

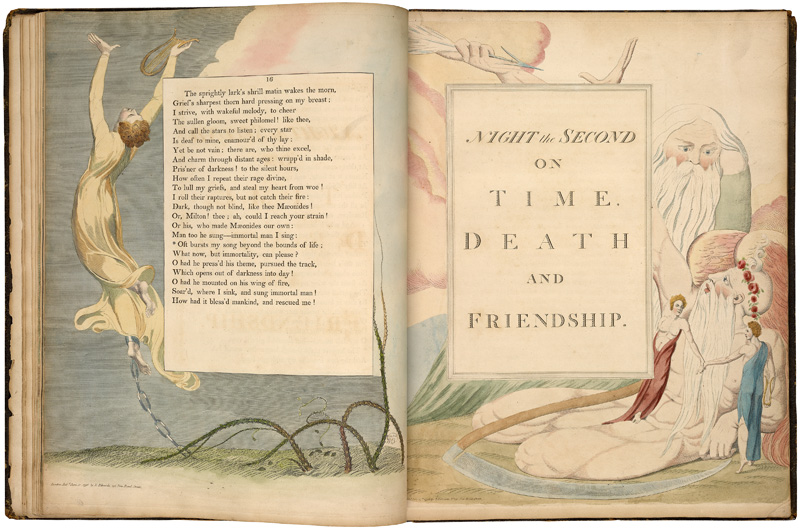

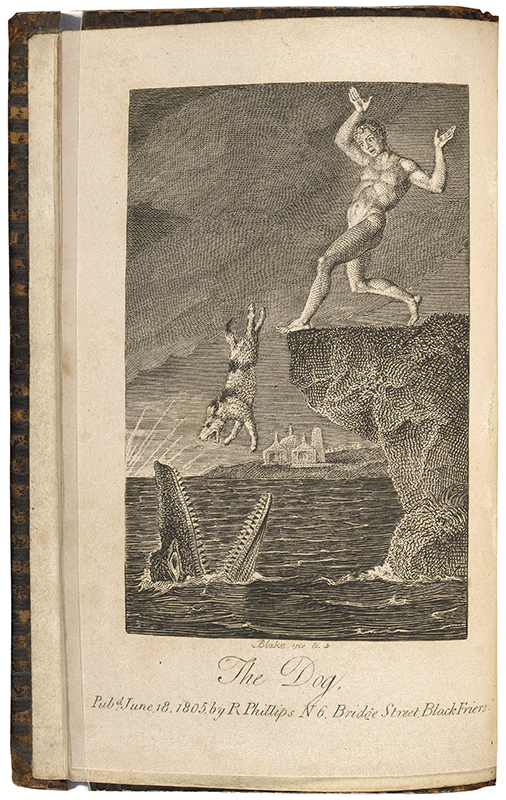

As for the watercolors and relief engravings that illustrate Blake’s poems—he had no use for oil on canvas—clearly they emerge out of the mid-eighteenth-century neoclassicism of Henry Fuseli and John Flaxman, with a nod to Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel. The spirit of these works is so close to that of an outsider artist that one is surprised to learn that Blake underwent a thoroughly standard apprenticeship and rose through the ranks of his profession. His simple engravings for J. G. Stedman’s book on a slave revolt in Suriname—a professional commission rather than a personal project—are perfectly competent (if not especially memorable) examples of mainstream British illustration of the 1790s.

In assessing Blake, we must acknowledge the nearly total anonymity in which he labored for most of his life. Few contemporaries ever heard of him and those who had probably knew him only as an artist: few of them ever imagined that there was a poet, much less a great poet, named William Blake. Although he was familiar with the works of William Wordsworth and Lord Byron, surely they knew little or nothing about him. After Blake’s death, Wordsworth read his poetry and commented that he was pitiable and no doubt mad; John Ruskin dismissed him as wild and unwholesome. Even Blake’s art, so prized today, was largely unknown beyond a small circle of admirers. Only toward the end of his life, as he was nearing seventy, did he become a spiritual mentor to a few artists of the younger generation: Samuel Palmer, George Richmond, and John Linnell. They were the ones who brought him to the attention of the Pre-Raphaelites and secured for him some measure of posthumous fame. As the nineteenth century progressed Blake’s fame increased, and certain psychedelic aspects of his art and poetry endeared him to the Beats and later to the youth culture of the 1960s.

Without question, Blake achieved greatness in both art and poetry, but more in the latter than in the former. His early lyrics are unsurpassed and even his generally incoherent prophetic poems possess a sublime, if inscrutable, beauty. His art, it must be said, does not rise to quite that level, relative to the finest achievements of the tradition of European painting from which they emerge. In 1959 art historian Anthony Blunt declared that the unbridled enthusiasm and praise for Blake only masked the artist’s real merits.

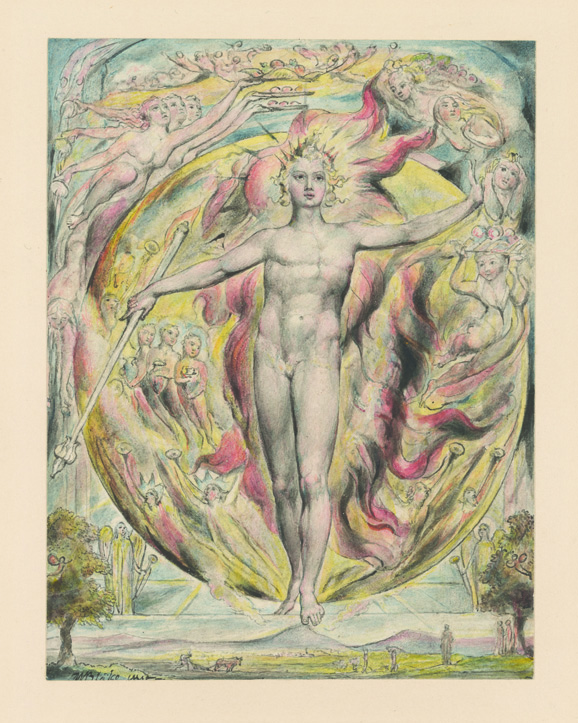

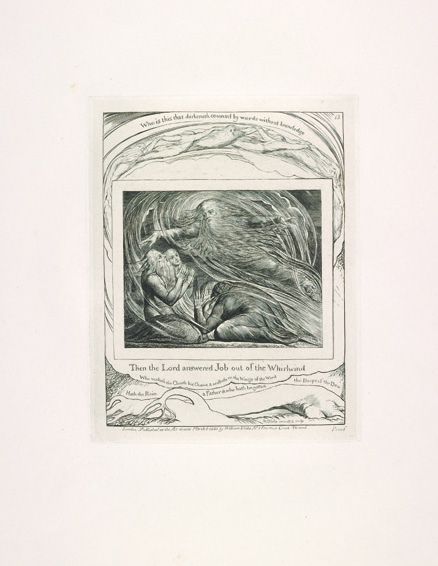

Blake reveals his artistic skill through an implicit mastery of drawing and composition in the demanding medium of watercolors. We see this mastery in The Sun at his Eastern Gate, portraying an airborne Helios surrounded by angels in a fiery orb, depicted with all the sinuous subtlety, anatomical tact, and chromatic splendor of the sixteenth-century mannerist Parmigianino. Meanwhile, the sureness of Blake’s drawing, his subordination of structure to pure line, can be seen in The Lord Answering Job Out of the Whirlwind, an engraved illustration of the Book of Job, from the end of Blake’s life.

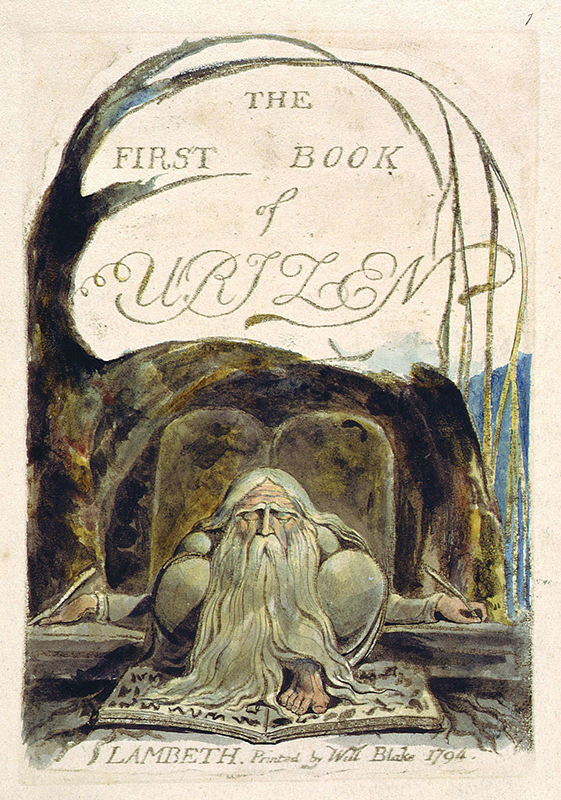

But perhaps the greatest merit of Blake’s art is its unmediated distillation of a great soul. An almost hallucinatory quality defines it, as though it were nourished and sustained on a steady flow of nitrous oxide. Something unfathomably deep emanates from the army of archetypes who populate his work, not only Helios and Job, but also Milton himself in old age (surrounded by angels and the constellations) and Urizen, a bearded old man of Blake’s own creation, as depicted on the title page of The First Book of Urizen. Like a lunatic or a child, Blake encounters and processes the world through pure feeling. And precisely because, in his apprenticeship, he assimilated the artistic conventions of his age, he was fully able to body forth the archetypes of his imagination without trivializing or neutralizing them.

Blake must be seen as a pivotal figure in the history of art. The defining difference between the painting of the Old Masters, which was dying out around 1800, and of romanticism, which just then was being born, is the difference between an almost complete obedience to cultural precedent and a radical rejection of that precedent in favor of the sovereignty of individual vision. In the art of Blake, more perhaps than in that of any of his contemporaries, we bear witness to that conflict as it plays itself out.

—James Gardner

William Blake’s World: “A New Heaven is Begun” online exhibition • Morgan Library and Museum, New York • themorgan.org