Paintings by William Henry Johnson are rarely available in today’s art market, as most of his work is secure in museum and university collections. The Smithsonian American ArtMuseum, for instance, owns more than one thousand works by this noted African-American artist. Nevertheless, the relatively nascent Johnson Collection, located in Spartanburg, South Carolina, has been able to acquire five works by this native son that illustrate three distinct modernist styles from various periods of his life, a life that was marked by poverty and mental illness, as well as by singular creativity.

Johnson is now regarded as one of the most important progressive artists of his time. Born to humble circumstances in Florence, SouthCarolina, he had few opportunities and little education; he studied and copied comic strips-the only form of art available to him in what was then a modest railroad town. At age seventeen he boarded a train heading north and settled in Harlem taking jobs as a hotel porter, short order cook, and dockworker before enrolling at the National Academy of Design in 1921.

In the five years Johnson attended the academy, he thrived, learning the basic skills of drawing and painting from plaster casts, live models, and still-life compositions. He won awards and gained the respect of his mentor, Charles Webster Hawthorne (1872-1930), who, in exchange for performing odd jobs, invited the aspiring artist to attend the Cape Cod School of Art in Provincetown, Massachusetts, for three summers. Later, when Johnson failed to win a fifteen hundred dollar traveling scholarship from the academy, Hawthorne raised money to help underwrite a trip abroad. To supplement his funds before leaving for Paris in November 1926, Johnson also did janitorial work in the studio of George Luks (1867-1933) for several months.

Working from a rented Left Bank studio once used by James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), Johnson immersed himself in the local scene and began to experiment with modern techniques under the influence of Parisian artists. He visited Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937), the expatriate black artist who had flourished in France. In early 1928 Johnson traveled south to escape the cold and expense of the French capital and sought out the picturesque fishing village of Cagnes-sur-Mer, near Nice, an art colony where Chaim Soutine (1893-1943) had also worked. Johnson had seen Soutine’s expressionist paintings in Paris and was enchanted by the narrow lanes and bright blue sky of the coastal hill town. The area’s square houses and red roofs lent themselves to Soutine’s penchant for distorted perspectives, which Johnson emulated in his Street of Cagnes-sur-Mer (Fig. 1). The buildings tilt dramatically as if viewed through a fish-eye lens. In a letter to Hawthorn, Johnson explained: “I am not afraid to exaggerate a contour, a form, or anything that gives more character and movement to the canvas.”1

While in Cagnes-sur-Mer, Johnson met the Danish textile artist Holcha Krake (1885-1944). They traveled around Europe with her sister and brother-in-law, German sculptor Christoph Voll (1897-1939), and soon Holcha and William fell in love. In November 1929 Johnson returned to America to reconnect briefly with the NewYork art world. No longer a student, he was recognized by the Harmon Foundation, a philanthropic organization whose primary mission was to reward distinguished achievements of African Americans in a number of fields, including literature, music, fine arts, business, science, and education. Coincident with the Harlem Renaissance, the foundation mounted a series of exhibitions from 1928 to 1933 that celebrated the accomplishments of black artists. In 1930 Johnson won the foundation’s gold medal, which carried with it four hundred dollars in prize money. The committee, which included his former employer George Luks, commended Johnson’s work: “We think he is one of our coming great painters. He is a real modernist. He has been spontaneous, vigorous, firm, direct; he has shown a great thing in art-it is expression of the man himself.”2

After several months in New York and a short sojourn to visit his family in South Carolina, Johnson returned abroad to reunite with Holcha, and, despite differences in language, culture, race, and age (she was sixteen years older than he), they were married in May 1930. They settled in Kerteminde, Denmark-like Provincetown and Cagnes-sur-Mer, a charming seaside hamlet and tourist destination. They exhibited their work together in hotel lobbies as well as art galleries, and Johnson occasionally traded paintings for art supplies or a new suit of clothes.

One of Johnson’s favorite sites was the harbor at Kerteminde, where he frequently painted the buildings along the shoreline, the small boats, and their reflections in the water. Boats in the Harbor, Kerteminde (Fig. 6), with its round, blazing sun and swirling staccato brushstrokes is reminiscent of paintings by Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890), which Johnson may have seen in Paris. The elevated viewpoint, bright colors, and thick application of paint in Garden, Kerteminde (Fig. 4), similarly recall the Dutch master’s late work. Adding to the tactile quality of both paintings is their burlap support, presumably used by Johnson for economic as well as expressive reasons. The garden in Garden, Kerteminde was a communal plot not far from the artist’s home where villagers grew flowers and vegetables. Some of the colorful flowers grown there are featured in Flowers in Blue and White Vase (Fig. 5), a painting that once belonged to Holcha’s younger sister Nanna Krake (1889-1968).

Despite the Depression and meager sales, the couple seemed content, happiest perhaps when they traveled, venturing as far south as Tunisia and as far north as the Arctic Circle. They lived and traveled in Norway for a period of almost two years; in Oslo, the collector Rolf E. Stenersen purchased several of Johnson’s paintings and arranged a meeting with the reclusive Norwegian expressionist Edvard Munch (1863-1944).

Returning to Kerteminde, the Johnsons soon learned that Voll, Holcha’s brother-in-law, had been fired from his teaching job in Karlsruhe and labeled a “degenerate” artist by the Nazis. Holcha and William decided to escape the coming war, arriving in New York on Thanksgiving Day, 1938. They took up residence in lower Manhattan, and Johnson soon found work under the auspices of the Works Progress Administration. Through his position teaching children at the Harlem Community Arts Center, he came into contact with other leading African-American artists such as Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000).

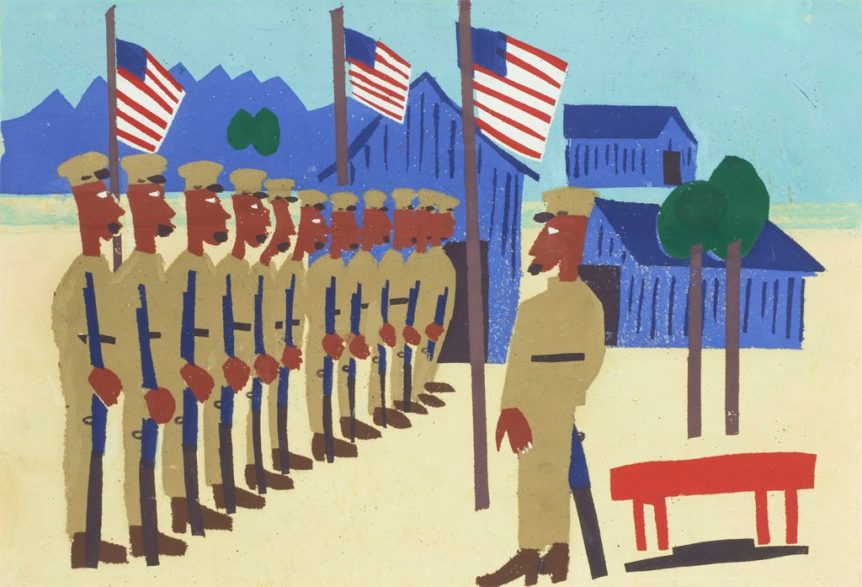

In New York Johnson’s work underwent a dramatic transformation. He abandoned European expressionism in favor of figurative work that drew variously from African art and folk and craft traditions, as well as from the art of children. Responding to proponents advocating a New Negro Art and influenced by urban life in the Jazz Age, Johnson’s late work became more narrative and emblematic, rendered in flat, bold shapes and colors. The scale of his work during the 1940s was often smaller and included works on paper. Training for War displays his new approach in a contemporary subject (Fig. 7). In his series on the UnitedStates war effort, Johnson used dark-skinned figures with African features and, in doing so, indulged in social commentary about the status of African Americans in the military. His use of pochoir-a form of screenprinting using stencils-reflects the increased popularity of the medium during the years the WPA programs were operative. Johnson explored a number of themes during this period, including series on religious subjects, rural scenes drawn from memory, pivotal figures in African-American history, and portraiture.

By the mid-1940s Johnson was facing significant personal challenges. The war had curtailed exhibitions and diminished sales; he and Holcha suffered a fire in their home/studio, and in 1944 she died of breast cancer. Johnson’s mental state began to deteriorate, and on a trip back to Scandinavia he was found wandering the streets of Oslo like a vagrant. He was sent to a mental hospital on Long Island where he spent some twenty-two years; he died there on April 13, 1970, the victim of syphilis-induced paresis.

The history of Johnson’s oeuvre is both complicated and controversial, and has been recounted by Steve Turner in William H. Johnson: Truth Be Told.3 For most of the decade following his hospitalization, the artist’s work and possessions were stored in a warehouse. A court-appointed lawyer attempted to sell everything for the sum of one hundred dollars but there were no purchasers. In 1956 the Harmon Foundation took possession of his paintings, which they later turned over to the National Collection of Fine Arts (now the Smithsonian American ArtMuseum).

Over the course of his brief career of just over twenty years William H. Johnson had created more than fifteen hundred artworks with only a few sales and a smattering of exhibitions. Nearly a half century after his death, however, he is now recognized for his distinctive approach to various styles and especially for his late work, when he discovered his own artistic voice. At the end of his career he achieved the goal he had articulated earlier to an interviewer: “My aim is to express in a natural way what I feel, what is in me, both rhythmically and spiritually.”

MARTHA R. SEVERENS is a curatorial consultant to the Johnson Collection.

1 Johnson to Charles Hawthorne, August 13, 1928, Charles W. Hawthorne Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C., as quoted in Richard J. Powell, Homecoming: The Art and Life of William H. Johnson (National Museum of American Art, Washington, D. C, 1991), p. 31. 2 “Exhibition to be Held of Work of Negro Artists,” Harmon Foundation press release, as quoted ibid., p. 41. 3 Steve Turner and Victoria Dailey, William H. Johnson: Truth Be Told (Seven Arts Publishing, Los Angeles, 1998). 4 Johnson quoted in Thomasius, “Dagens Interview: Med Indianer-og Negerblod I Aarene. Chinos-Maleren William H. Johnson fortœller lidt om sin Afrikarejse, primitv kunst, m.m.,” Fyens Stiftstidene, Odense, Denmark, November 27, 1932, as quoted by Richard J. Powell, “Trembling Vistas, Primal Youth: William H. Johnson’s Painterly Expressionism, 1927-1935,” in William H. Johnson: An American Modern, ed. Teresa G. Gionis (University of Washington Press, Seattle, Wash., 2011), p. 30.