William Hodgson. That is the name of a previously unidentified artist who worked in Virginia in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. For decades, art historians and collectors called him simply the “Payne Limner” due to his creation of ten portraits for the Archer Payne family of Goochland County, Virginia. First published in 1916, the author noted they were by an artist “who was said to have considerable talent as a painter.”1 The first comprehensive study of his work, in 1981, attributed three additional portraits from the city of Richmond and Henrico County to the unknown artist’s hand, bringing the total to thirteen.2 The recent discovery of a second group of portraits depicting the Seabrook family of Richmond and Norfolk, Virginia, has generated new research and identified William Hodgson as the Payne Limner. Two of the earliest American hunt scenes (see Fig. 7) and three additional portraits, including one tied directly to the painter’s family (Fig. 11), can now be assigned to Hodgson, bringing the current number of his known paintings to twentythree. Together, these works illustrate the life of a British tradesman-turned-artist whose transatlantic career moved from the center of London’s craftsman community on St. Martin’s Lane to Amsterdam, Norfolk, and, finally, Richmond, where he produced an impressive body of early southern portraiture over the course of two decades.

Hodgson’s name first appears in British records on January 6, 1772, when the twenty-four-year-old tradesman and his fiancée, Margaret Tatum, wed at the church of St. Paul’s, Covent Garden, in central London.3 The following year, their first child, William (b. 1773), was christened at the same church.4 The Hodgsons had at least five more children: Charlotte (b. 1777), Sophia (b. 1779), Robert (b. 1781), Joseph (b. 1784), and Elizabeth Ann (b. c. 1787).5

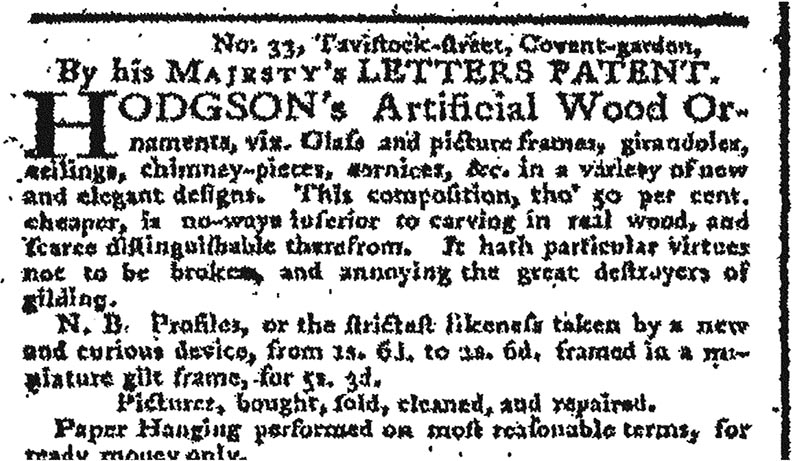

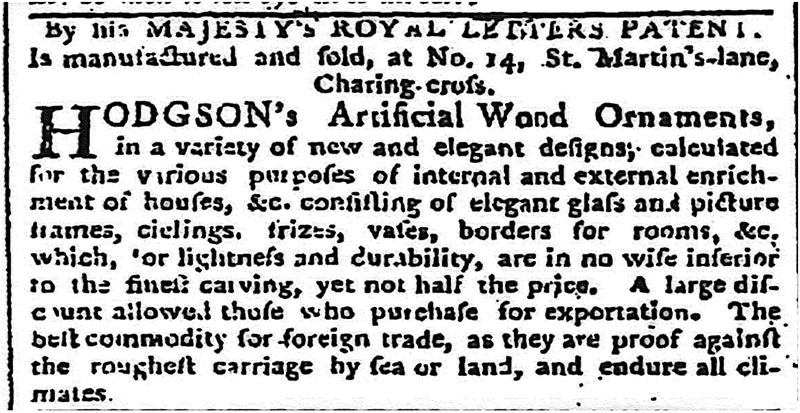

Hodgson was identified as a carver living in the parish of St. Andrew, Holborn, when he and William Whitlock, an embroiderer in St. Paul’s, Covent Garden, received a royal patent on July 15, 1772. “Artificial Wood” was the name they gave to their formula for a material—consisting of cartridge paper, water, glue, wheat flour, beech-tree sawdust, and hemp—used for ornamental carving, casting, and modeling.6 Within a few years, Hodgson advertised in the London newspapers, “Hodgson’s Artificial Wood Ornaments, in a variety of new and elegant designs” (Fig. 4b). He proclaimed that his product was suitable for “glass and picture frames, cielings [sic], frizes [sic], vases, borders for rooms, &c.” Half the price of carving and cheaper than papier-mâché, he asserted it was also highly durable and suitable for exportation to overseas markets. If sales for artificial wood were slow, Hodgson also offered wallpaper installation “on most reasonable terms, for ready money only” (see Fig. 4a).

By 1777 Hodgson had moved from Tavistock Street, near Covent Garden, to 14 St. Martin’s Lane in the heart of London’s artistic and cabinetmaking district. The lane had been home to the drawing school for aspiring young artists established by William Hogarth (1697–1764) in the 1730s. Hodgson’s neighbors included two of London’s most important furniture designers, Thomas Chippendale (1718–1779) and William Hallett (1707–1781), and a few blocks away stood Old Slaughter’s Coffee House, where many of London’s leading artists gathered for convivial drinks and conversation. Hodgson may have first trained as a carver, but he was already dabbling in the artist trade, and noted in advertisements that he bought and sold pictures, cleaned, and repaired them. He offered “Miniature Profiles” by a “new and curious device,” while his pastel portraits and “Paintings in miniature” were priced from one to two guineas, and “nothing required if not a striking Likeness.”7

Exactly where Hodgson trained is unknown. Like many craftsmen of the period, he probably received part-time instruction in drawing while he was apprenticed to a professional carver. Drawing schools proliferated in mid-eighteenth-century London, and especially on St. Martin’s Lane. Manufacturers believed in the commercial utility of drawing, a word closely akin to “design.”8 The 1750s witnessed a remarkable growth of design in nearly all the decorative arts—furniture, architecture, plasterwork, ceramics, silverwork, textiles—and possessing the technical skills to draw and to interpret the most “new and elegant designs” was particularly important to tradesmen. Hodgson’s variety of professional endeavors point to the London background from which he emerged as a carver, composition ornament maker, profile cutter, miniature painter, and ultimately a portrait and landscape artist.

He may have studied drawing with Edward Hodgson (1719–1793), possibly a close relative, who advertised in London teaching figure, flower, ornament, and landscape drawing.9 Twenty-nine years apart in age, Edward and William worked in the same general area of London. Edward also instructed ladies in flower painting and creating patterns for needlework, skills related to those later taught in Richmond by William’s wife, Margaret, and it is plausible that William Hodgson and Margaret Tatum first met in Edward Hodgson’s drawing classes.

By 1781 the Hodgsons and their children had moved from London to Amsterdam, where their son Robert was christened at the English-speaking Presbyterian Church. They stayed in the Netherlands only a few years, for by the fall of 1783, and possibly earlier, they were in Virginia, where William witnessed the will of another likely kinsman, Francis Hodgson (d. 1784), a former sea captain engaged in the Norfolk shipbuilding industry.10

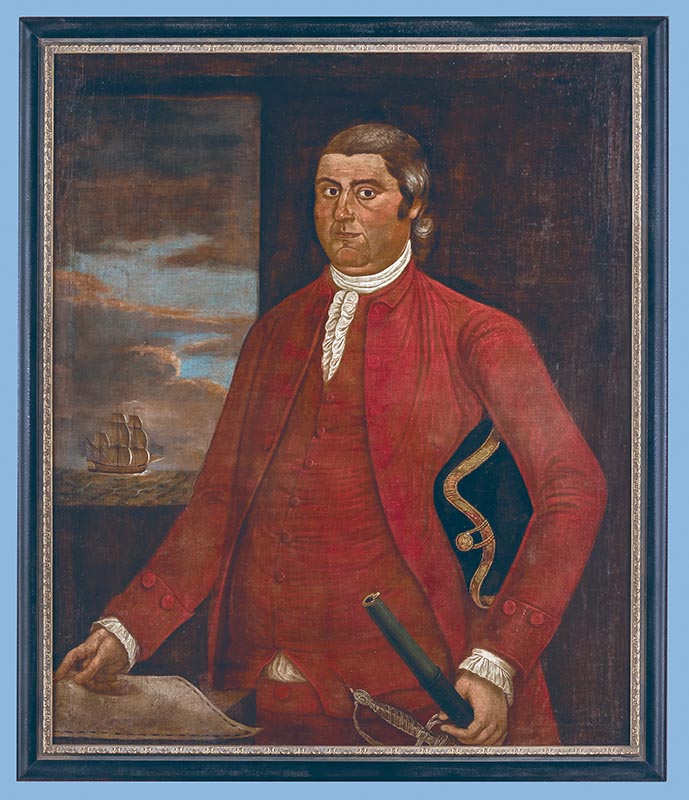

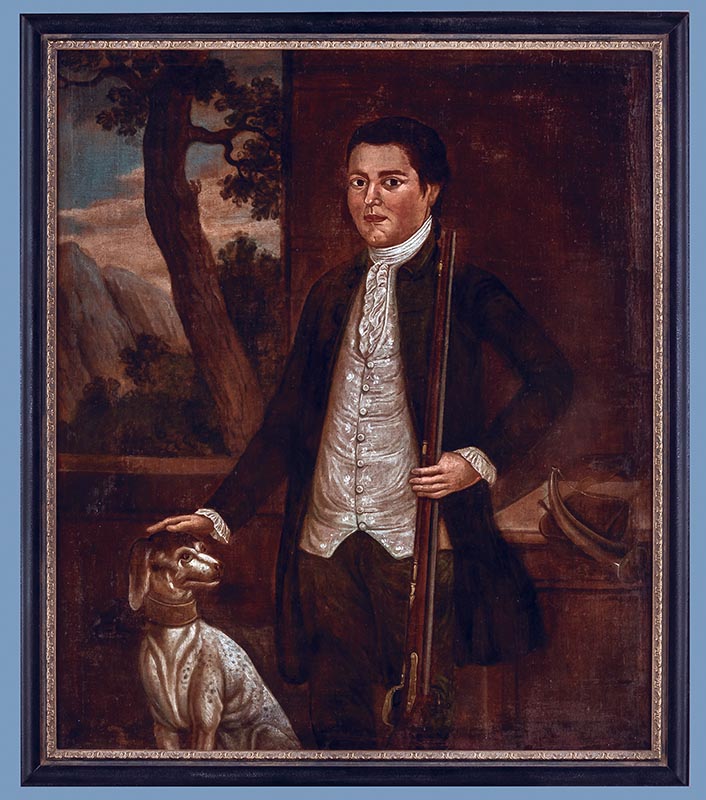

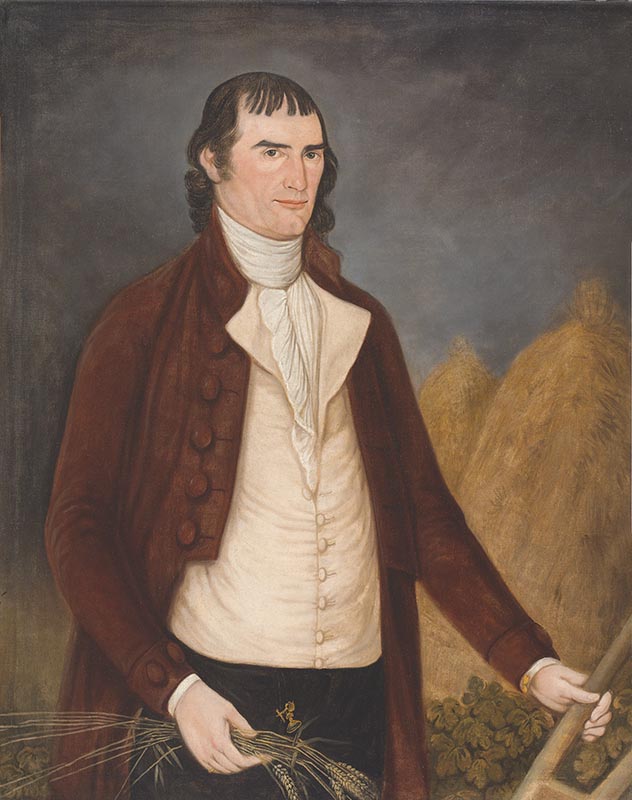

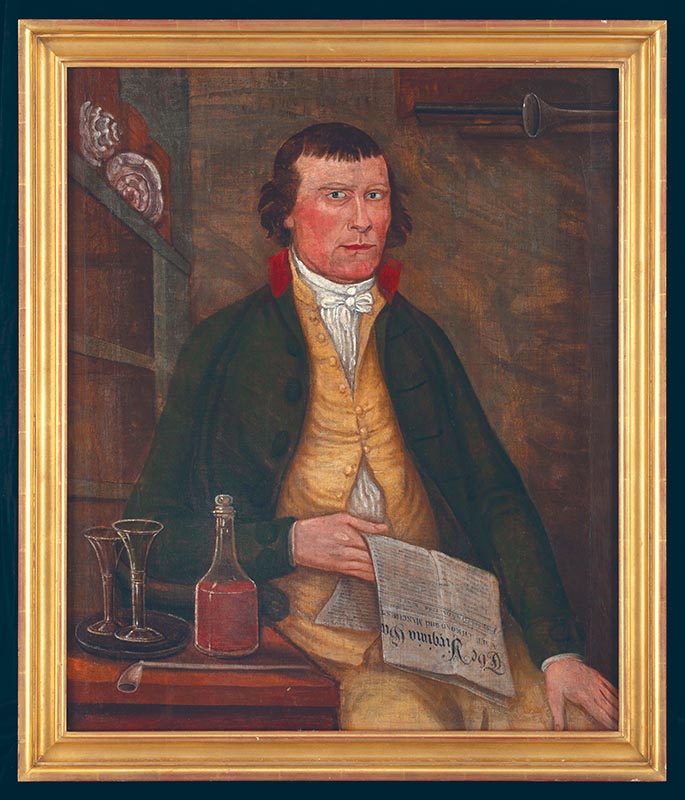

It was Francis’s seafaring connections that apparently led William to his first known client for large-scale oil portraiture in America, Nicholas Brown Seabrook (Fig. 1). A Norfolk ship captain, Seabrook and Francis Hodgson had exchanged correspondence as early as 1778.11 During the American Revolution, Seabrook commanded an eight-gun, sixty-ton privateer, the Liberty, and invested his profits in downtown Richmond real estate and a Hanover County plantation called Dungaroon.12 The artist received a commission to paint the captain’s entire family, the first of at least three large family commissions that Hodgson received. In addition to the captain, Hodgson painted at least four other Seabrook family portraits, including his wife Mary (Fig. 2), their eldest son John (Fig. 3), and the two youngest daughters, Mary (1777–1796) and Betsy (1780–1783).

By 1788 Hodgson had relocated to Richmond, where Margaret advertised that she had kept a “school at Norfolk” for “children of the most respectable families,” but her business was now in Richmond, “opposite Mr. Trower’s tavern, for instructing young ladies in . . . Reading, writing, ciphering, and all kinds of needlework.”13 Margaret’s needlework skills may have been tied to the London embroiderer William Whitlock and flower painter Edward Hodgson. Her school would have contributed to the family’s financial stability with much needed income.

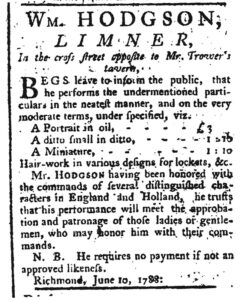

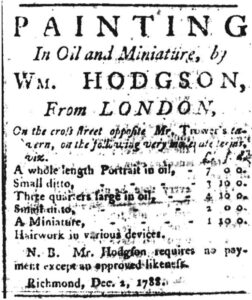

On June 10, 1788, William Hodgson placed his own advertisement in the local newspaper proclaiming himself a “Limner” (Fig. 4c). He noted that he had been “honored with the commands of several distinguished characters in England and Holland” and “trusts that his performance will meet the approbation and patronage of those ladies or gentlemen, who may honor him with their commands.” Like his London advertisements for portrait miniatures, he proffered “no payment if not an approved likeness.” He also offered “hairwork in various designs for lockets” and noted that his portraits could be ordered in three sizes: large, small, and miniature. In December he elaborated and noted that paintings “in Oil and Miniature” by “Wm. hodgson, from london,” could be commissioned in five sizes at different prices: “A whole length Portrait in oil” for £7; a “Small ditto” at £3 10s; “Three quarters large in oil” at £4 10s; a “Small ditto” at £2; and “A Miniature” for £1 10s” (Fig. 4d).

Hodgson’s canvases varied in size from a standard 34 by 21 inches to a monumental 56 by 69 inches. Of his known Virginia portraits, three are half- or waist-lengths depicting adults, fourteen are three-quarter lengths of adults and teenage children, while his four whole-length portraits seem to have been reserved for young children. In style and pose, his images imitate mid-eighteenth-century London fashion, although Hodgson’s manner of painting and his handling of form and spatial arrangement were idiosyncratic. Among the characteristics associated with his painting style is a tendency to exaggerate some anatomical details while giving great care and accuracy to others. His subjects’ faces are usually meticulously painted as convincing lifelike portrayals. He was less skilled or less attentive rendering other features such as arms and hands. Forearms often have exaggerated muscles, and hands are sometimes awkwardly posed with fingers unnaturally bent. Hodgson also had difficulty with foreshortening and placing his sitters’ bodies in space. They often seem flat and lacking in three-dimensional depth. These characteristics appear in works spanning Hodgson’s career, beginning with the Seabrooks in the early 1780s, continuing through his commissions for the Paynes and Truehearts in the 1790s, to his rendering of Elizabeth Christian Humber around 1803, although her portrait shows considerable improvement in modeling and foreshortening (see Fig. 9).

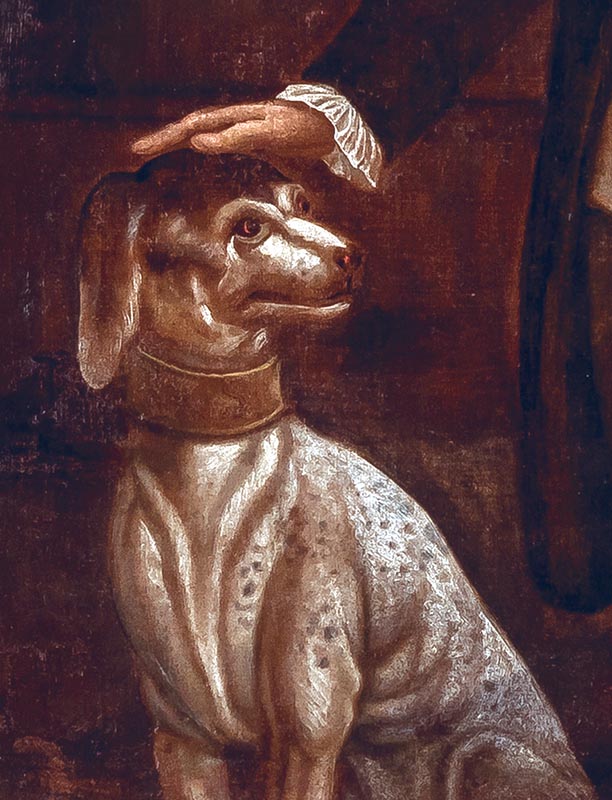

The artist’s tendency to exaggerate muscular body structure is also seen in his drawing of animals, particularly in the necks and shoulders. The dogs and horse in one of his hunt scenes and the dogs in his Payne and Seabrook family portraits have these distinguishing treatments (Figs. 8a–c). Hodgson seems to have been experienced at painting faces, perhaps because he had first trained in painting miniatures and small portraits.

Hodgson was familiar with the poses and compositions that were popular in mid-eighteenth century London, and he used many of the ones employed by John Durand (c. 1745–after 1782), a painter whose London background and artistic style were remarkably similar to his. Durand came to America in 1767, worked in New York and Connecticut, and painted in the Norfolk and Petersburg areas of Virginia until around 1782, approximately when Hodgson arrived.14 Hodgson’s portraits of Mr. and Mrs. Seabrook and their son John have the typical eighteenth-century poses used by Durand, with sitters faced forward or slightly turned, stances meant to reflect the proper deportment and elegance that were important to wealthy merchant-planters during the period. As Hodgson’s career progressed, he modified and experimented with the poses as well as the settings into which his sitters were placed. His large canvas with full-length figures of Alexander Spotswood Payne, his brother John Robert Dandridge Payne, and their enslaved African American nurse is a fine example of Hodgson’s ability to create unique, complex compositions personalized with clothing and objects, such as hunting gear and birds that were known to the sitters (Fig. 5). Hodgson’s sensitive inclusion of enslaved African Americans in portraits of this period was exceedingly rare.

A defining characteristic of Hodgson’s work is a surprising fidelity when he painted material details, such as the ship owned by Nicholas Brown Seabrook (see Fig. 1), the floral silk fabric of Mrs. Seabrook’s dress (Fig. 2), the red-bellied woodpecker in the Payne boys’ portrait, and the Virginia Gazette held by Daniel Trueheart (Fig. 9). These vignettes faithfully replicate objects that existed in his sitters’ lives and had meaning for them; they were not formulaic props commonly used by many London-trained portraitists. Nonetheless, Hodgson’s ability to capture these objects and details likely reflects his London training in drawing and his skill in transitioning from sketching forms to painting them in oils.

While Hodgson worked in Richmond and its surrounding area, he seems to have been a true jack-of-all-trades. In addition to portraits, miniatures, and hairwork for jewelry, he supplied composition ornament and carved architectural woodwork for buildings. In 1788 Virginia’s Director of Public Buildings commissioned Hodgson to carve twelve architectural brackets and twenty Ionic capitals for the original Senate and Council chambers of Virginia’s new capitol building.15 In 1796 he landed what may have been his most prominent commission, installing in the capitol rotunda the life-size statue of George Washington by French sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon (Fig. 10). For its placement, and repairing and relaying the floor, Hodgson received a payment of thirty pounds.16

Throughout these years, Hodgson traveled for portrait commissions from Richmond to the adjacent counties of Goochland and Hanover, and he returned at least once to Norfolk. He advertised there in 1798 that he continued “to take Likenesses in Oil, &c. on very moderate terms” and that “likenesses of persons resident in this place, may be seen in the large room at Lindsay’s Hotel.”17 It was his final advertisement.

Hodgson’s last known portrait, and the one critical to his identification as the Payne Limner, depicts Elizabeth Christian Humber, the wife of John Humber (c. 1735– 1806), an upper middling planter at Air Hill in Goochland County (Fig. 11). The Humbers enjoyed close, direct ties to the artist, as on January 8, 1803, Hodgson posted bond in Richmond for the marriage of his daughter Charlotte to the Humbers’ son, William Humber of Goochland County. Hodgson probably painted Elizabeth’s portrait around the time of their children’s wedding, and it descended in the family of the sitter and the artist’s great-grandson and namesake, William Hodgson Humber (1844–1914).

William Hodgson died in Richmond on July 28, 1806, aged fifty-eight, and a sandstone monument marking his grave was erected in the cemetery at St. John’s Episcopal Church.18 While there were no paints, brushes, or art equipment of any kind listed among his possessions, his estate sale included “60 composition moulds” and “1 Nest of drawers with a quantity of composition,” an ongoing indicator of his career as the patentee of Hodgson’s Artificial Wood.19 The following February, Margaret Hodgson advertised the reopening of her school with an expanded curriculum that now included, interestingly, “Reading, Writing, Plainwork, Marking and Embroidery—Also, Drawing and Painting.”20

In the years immediately following the Revolutionary War and the naissance of a new country, the Hodgsons enjoyed a clientele eager for portraits, as images of various sizes and types were sought by an emerging middle class. Typical of artists with a background in trades, William engaged in multiple forms of decorative work and painted everything from miniatures to landscapes to whole-length portraits. His and his wife’s careers provide a rare account of an early American crafts couple earning their living. In no other case can the diversity of services offered by a late eighteenth- or early nineteenth- century husband and wife be more fully documented. The authors hope that additional works by William Hodgson, and perhaps Margaret, particularly miniatures, profiles, and landscapes, will be discovered and culminate in a more comprehensive publication and museum exhibition.

1John M. Payne, “Payne Portraits,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, vol. 24, no. 2 (April 2016), p. 200. 2Elizabeth Thompson Lyon, “The Payne Limner” (master’s thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, 1981). 3The Registers of St. Paul’s Church, Covent Garden, London, Vol. III: Marriages, 1653–1827, ed. William H. Hunt (London: Harleian Society, 1907), p. 255. 4William Hodgson, October 18, 1773, St. Paul’s, Covent Garden, London, “England Births and Christenings, 1538–1975,” online database at familysearch .org. 5Charlotte Hodgson, October 28, 1777, St. Martin-in-the-Fields, London, and Sophia Hodgson, November 1779, St. Clement Danes, London, “England Births and Christenings, 1538–1975”; Robert Hodson [sic], February 11, 1781, English Presbyterian Church, Amsterdam, “Netherlands, Archival Indexes, Vital Records,” online database at familysearch.org. Joseph T. Hodgson’s obituary identifies him as a native of Richmond, aged sixty-three, at the time of his death on July 16, 1847; see Jonathan K. T. Smith, Genealogical Abstracts from Reported Deaths, The Nashville Christian Advocate 1847–1849 (Jackson, TN: J. K. T. Smith, 2003), p. 23. 6English Patents of Inventions, Specifications, Volumes 1001–1110 (London: H. M. Stationery Office, 1856), no. 1011, pp. 34–35. 7London Morning Post and Daily Advertiser, December 6, 1778. 8Anne Crookshank and the Knight of Glin, The Painters of Ireland c. 1660–1920 (Dublin: Barrie and Jenkins, 1978), p. 69, n. 1. 9London Gazetteer and New Daily Advertiser, May 2, 1764, September 12, 1765. Edward Hodgson is recorded as a drawing master teaching at White Hart Court, Bishopsgate in 1763; Mitre Court, St. Paul’s Church Yard in 1764; Oxenden Street, Haymarket in 1767; Greek Street, Soho in 1769; Little St. Martin’s Lane in 1775; and 123 Jermyn Street from 1782 until his death. See also his entry in the Dictionary of National Biography, reprint of reissued ed., vol. 9 (London: Oxford University Press, 1921–1922). 10Will of Francis Hodgson, written June 5, 1784, recorded July 15, 1784, Norfolk County, Virginia, Will Book 2, p. 197. While Hodgson witnessed Francis’s will on June 5, 1784, he was in Virginia the previous year, evidenced by his portrait of Nicholas Brown Seabrook’s youngest daughter Betsy (1780–1783), who died on October 2, 1783. 11“Virginia Colonial Records Project, Survey Report No. 5964,” p. 8, microfilm at the Library of Virginia, Richmond, also available online at ancestry.com. In 1778 Francis Hodgson of the sloop Seaflower is documented delivering a letter in Norfolk to Captain Seabrook, who was captain and part owner of the Liberty with merchants John H. Norton and Samuel Beale of Williamsburg, Virginia. 12John E. Stillwell, Historical and Genealogical Miscellany, Early Settlers of New Jersey and their Descendants, vol. 4 (New York, 1916), pp. 242–246. 13Virginia Gazette and Daily Advertiser, Richmond, January 17, 1788. 14For more information on John Durand’s career in Virginia see Carolyn J. Weekley, Painters and Paintings in the Early American South (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), pp. 279–292 15For Hodgson’s work at the Virginia Capitol and his career as an architectural and furniture carver in Richmond, see Sumpter T. Priddy III and Martha C. Vick, “The Work of Clotworthy Stephenson, William Hodgson, and Henry Ingle in Richmond, Virginia, 1787–1806,” in American Furniture 1994, ed. Luke Beckerdite (Milwaukee, WI: Chipstone Foundation, 1994), pp. 206–233. 16Calendar of Virginia State Papers, Volume VII, May 16, 1795 to December 31, 1798, ed. H. W. Flournoy (Richmond, 1890), p. 373. 17Norfolk Herald, April 10, 1798. 18Judith Bowen-Sherman, The Burying Ground at Old St. John’s Church (Richmond, VA: St. John’s Episcopal Church, 2011), p. 26. 19Inventory and Account of William Hodgson, February 21, 1807 and November 9, 1807, Richmond Hustings Deed Book 5, 1807–1810, Richmond, pp. 10–11, 259–260 20Richmond Enquirer, February 6, 1807.

ROBERT A. LEATH, president of the Classical American Homes Preservation Trust, is the former chief curator at the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts.

CAROLYN J. WEEKLEY is the former Juli Grainger Curator at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and the author of Painters and Painting in the Early American South (2013).