American artist Winslow Homer is best known for his work in oil and watercolor, but he began his career in the newsroom making images for illustrated periodicals. As a young artist, Homer contributed to Ballou’s Pictorial in Boston, and famously covered the Civil War for Harper’s Weekly. This chapter in Homer’s life is well studied: scholars have catalogued his illustrations, considered the relationship between his graphic work and his paintings, and closely examined the places, people, and events he depicted during and after his three trips to the front.

But the Civil War is not the only context that informs Homer’s early work. The artist contributed to Harper’s at a revolutionary moment in the history of journalism, when a new type of publication, the illustrated weekly, offered Americans topical, timely images of current events for the first time. In the 1850s a group of Boston and New York entrepreneurs took advantage of innovative printing technologies to publish the news in this new, image-rich format. Unlike daily newspapers, with their columns upon columns of unbroken text, illustrated weekly journals like Harper’s, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper,and the New York Illustrated News presented illustrations of current events alongside written reports. “Worldwide, in little more than a decade, [the weeklies] . . . altered the face of magazine journalism,” wrote art historian David Tatham. For the first time, it was possible to see as well as to read the news of the day.

When we think of an image of a current event, we think of the camera and the intrepid photojournalist. Photographers were active in the mid-nineteenth century, but photography had not yet matured into a mass-media technology. Photographs were difficult to reproduce in print, and photographic equipment was cumbersome and incapable of capturing moving subjects. Artists, however, could be dispatched to the scene to sketch, and the weeklies relied on teams of draftsmen to prepare their drawings for publication. The artists’ stature and importance increased during the Civil War, when Northerners were desperate for up-to-date reports from, and images of, the front lines. In Beyond the Lines, his study of “pictorial reporting,” Joshua Brown explains that “historians of the Civil War have recognized its visualization as a unique feature of the conflict.” Eager for “pictures that conveyed stories and visual evidence about the progress of the war,” readers gravitated toward the weeklies, and their circulation (and profits) swelled as the conflict ran its course.

Like Thomas Nast, Alfred R. Waud, and the many other illustrators who covered the war, Homer operated within the constraints of the newsroom. The exhibition at Harvard explores the connection between his work and the visual strategies and market pressures that shaped the new era of pictorial journalism. The show brings together Homer’s Civil War illustrations and a select group of related paintings and watercolors, many drawn from Harvard’s collection.

Then, as now, the news was a deeply competitive industry. During the Civil War, accurate, up-to-date reporting attracted readers and secured their loyalty. Each of the three major illustrated weeklies emphasized the exceptional reliability of its illustrations, while questioning the trustworthiness of the competition. Self-promotion was rampant: “Wepublish [a picture] by a person who was present” (Harpers, 1860). “We select the most striking . . . and present the only correct and authentic pictorial illustration of the war” (Leslie’s, 1861). “We have avoided the errors of the other illustrated papers, which have given bogus drawings as ridiculous as untrue, instead of trustworthy pictures” (New York Illustrated News, 1862).

Comments like these resonate today, as claims of fake news and doctored images permeate cable television and the internet. In some ways, mid-nineteenth-century Americans thought about the media in the same way we do: skepticism prevailed, and consumers often questioned the veracity of what they were seeing. They were right to express doubt. The process of preparing an image for publication involved many hands, and sketches by Homer and his peers were many steps removed from the battlefield by the time they appeared in print. At Harper’s headquarters in New York, a Homer sketch was transferred to a wooden block by a team of specialist engravers. “Pruners” were expert at cutting sky and foliage; “tailors” at drapery and cloth; and “mechanics” at weapons and machinery. These specialists made quick work of the sketch, and then used the new technology of electrotyping to transfer the carved block to a metal plate suited to large-scale print runs.

Though Harper’s claimed that most of its illustrations were “drawn on the spot” by a single artist, period accounts suggest that sketches were often “elaborated” in the engraving room to appear more real. “A line out of doors,” one illustrator recalled, “means as much as a dozen in the studio.” It is difficult to establish the extent to which Homer’s drawings were embellished, if at all, because many were destroyed in the process of engraving. But the possibility of elaboration, and the larger set of market pressures active in the Civil War newsroom prompt the questions: How did Homer and his fellow artists and editors convince the reader that their images were reliable accounts? How was accuracy expressed visually? In short, what steps could an artist take to fashion illustrations that appeared “drawn on the spot”?

In Homer’s case, the answer rests in the illustrations themselves. Looking closely suggests that Homer drew on and helped to develop a range of visual strategies—what might be called an “aesthetic of the eyewitness”—to invest his images with the authority of the firsthand account.

This aesthetic takes three principal forms. First, Homer often depicted himself as an eyewitness. Several of his illustrations feature self-portraits of the artist in the field at work. Consider his composite image News from the War (Fig. 6). This montage of seven vignettes depicts some of the ways that information about the war was shared. News arrives by letter, bugle, word of mouth, and via the “newspaper train.” At lower left, the viewer’s eye lands on an image of Homer himself. Seated on an empty barrel, he sketches a pair of towering soldiers as a crowd looks on. This self-portrait signals to the skeptical reader that Homer was literally “on the spot,” sketching what he encountered in the field.

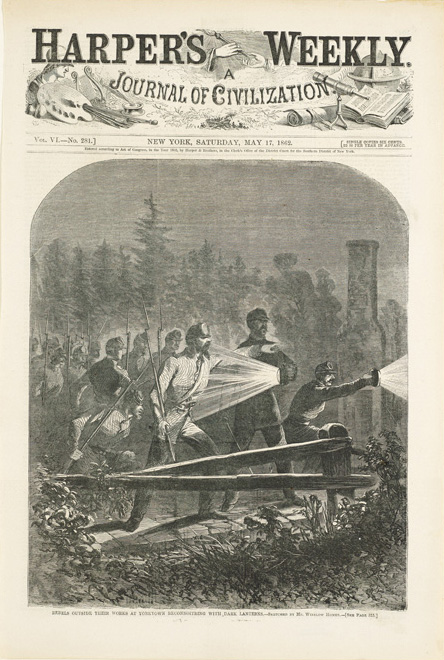

In other illustrations, Homer intimated his presence in a more subtle way. Rebels Outside Their Works at Yorktown Reconnoitring with Dark Lanterns (Fig. 4) dramatizes the stealthy Confederate brigades that prowled the front lines at night. Artists were required to maintain a safe distance from the enemy, and it is unlikely that Homer witnessed this scene. Yet the image invites the viewer to imagine the artist slinking around the bushes in the foreground in pursuit of his quarry. Homer places himself among the group of artists whose bravery in the field Harper’s extolled at the end of the war: “with their pencils in the field, upon their knees, upon a knapsack . . . in the dusk twilight, with freezing and fevered fingers,” they created “history quivering with life.”

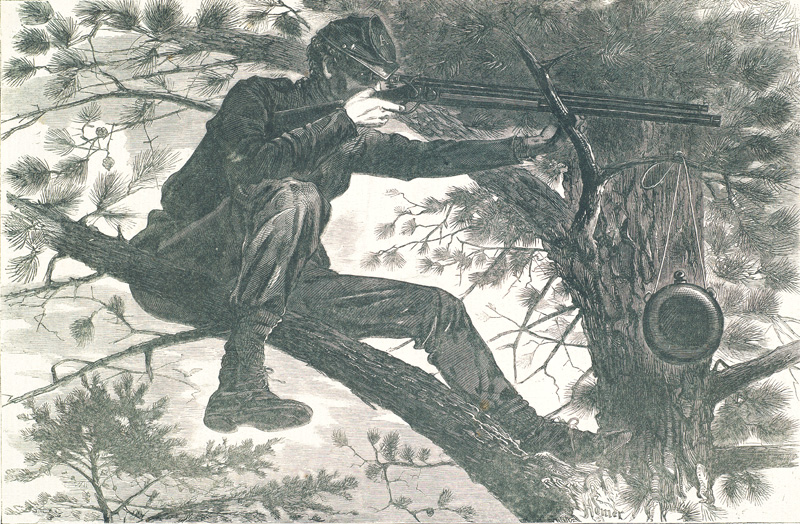

A third witnessing strategy is evident in Homer’s iconic illustrationThe Army of the Potomac—A Sharp-Shooter on Picket Duty (Fig. 2). This print famously portrays a Union marksman hiding in a tree as he squints through his telescopic sight, aiming his rifle at an unseen target. A portrait of the brutal modernity of a war in which one could be killed without warning, Sharp-Shooter gains much of its charge from the specificity of the scene. Details like the sniper’s regimental cap, his distinctive profile and position in the tree, and his loosely tied shoelaces convince the viewer that the sharpshooter is no fictive allegory, but the recorded image of a real soldier in a real place.

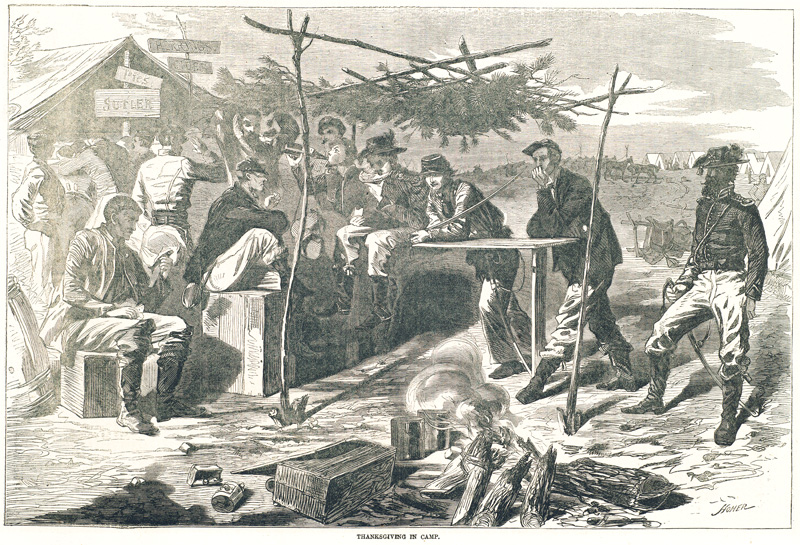

Many of Homer’s illustrations include such seemingly incidental details. Giving the impression of a world observed rather than imagined, Homer lavished attention on the cut and colors of uniforms and insignia, and the material culture of army life. The folds of soldiers’ canvas tents; the intricacies of horses’ bridles, saddles, and tack; and the particularities of the cook’s buckets and barrels all elicited his attention. Homer’s skies were specific too. Even in black and white, they suggest the stormy clouds, passing showers, or bright sunshine of a particular atmospheric and climatic moment. The editors at Harper’s likely encouraged the gathering of such content. Recalling his time as an artist-correspondent at Frank Leslie’s, James E. Taylor recalled being pressed on the importance of missing nothing to ensure the fidelity of his work: “not even sticks, stones and stumps . . . regardless of flying bullet and shell.”

At times, though, this fidelity was compromised. The artists’ and editors’ commitment to eyewitness observations had its limits. Rendering combat was a particular challenge. Fighting typically took place out of the artist’s view. “Few were the artists who were moved to translate to canvas the fury and medley of the battle-field,” one critic later recalled. While some sketched battles from afar with the help of binoculars, Homer took the more convenient path and relied on the conventions of military art. Stiff and formulaic illustrations like War for the Union 1862—A Calvary Charge show how difficult it was to render such subjects convincingly and help to explain why Homer favored scenes of life in camp.

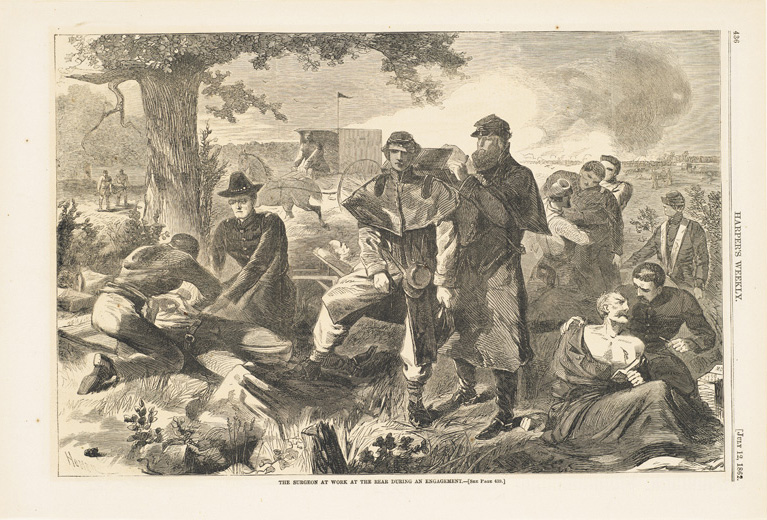

Homer also faced the hurdle of making combat palatable to Harper’s readers, many of whom were Northerners who had loved ones in the field. In one 1862 illustration, The Surgeon at Work at the Rear during an Engagement (Fig. 7), he depicted the rear lines where medical staff looked after the wounded. Exuding calm and confidence, the surgeon stands in the center of the print, removing supplies from an orderly’s backpack, as a horse-drawn ambulance rushes past in the background. The image includes several wounded men, yet Homer artfully hides their injuries. The soldier at right is wrapped in a blanket; at left, a prone figure is concealed by the body of the person tending him. In contrast to a more direct work like Sharp-Shooter, Homer’s sanitized portrait softened the brutality of the war.

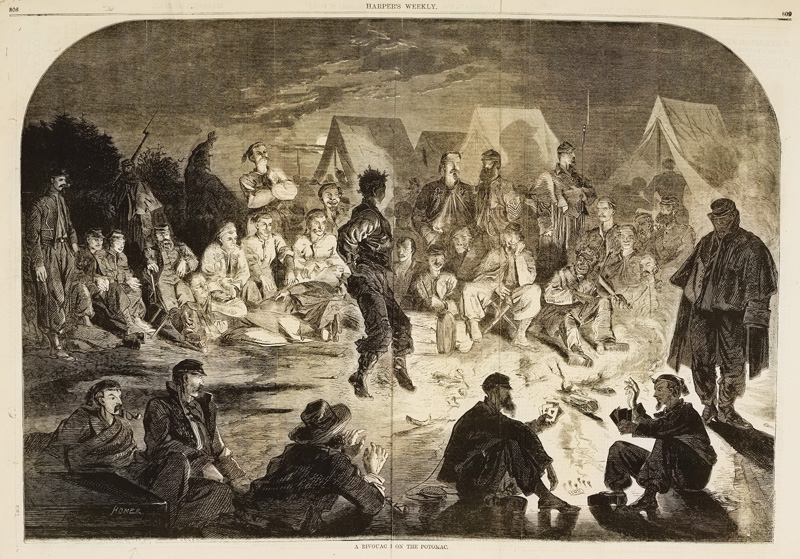

Homer and his editors sometimes strayed from the observable for reasons that are more problematic. The artist inhabited a racist world, and his efforts to present himself as a truthful witness sometimes involved distorting reality to fit the biases of his audience. Nowhere was this tendency clearer than in his portrayal of men and women of African descent. The racism in Homer’s Civil War images was sometimes overt, as was much of the accompanying coverage in Harper’s. Homer’s 1861 illustration A Bivouac Fire on the Potomac depicts a circle of Union troops watching two black men, one dancing and the other—caricatured with swollen lips and a toothless grin—playing a fiddle (Fig. 11). The print, which dates from a moment when white Northerners were expressing growing anxiety about living alongside formerly enslaved people, shows that the weeklies’commitment to accuracy only extended so far. When the question of slavery was at stake, offensive and demeaning stereotypes often trumped eyewitness reporting, even in the case of a pro-Union, republican journal like Harper’s.

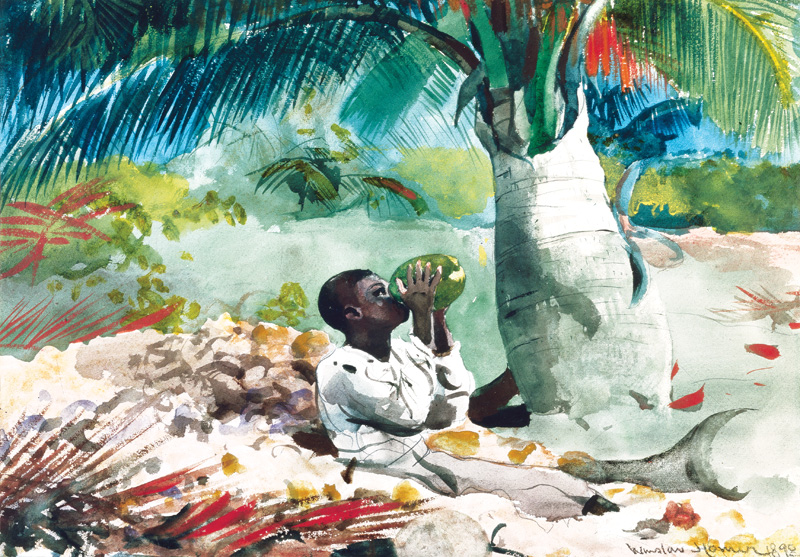

A man of few words, Homer said little about his years as an illustrator. But his biographers report that he was ready to leave the news business behind almost as soon as he started. Harper’s paid the bills, Lloyd Goodrich explains, but from an early age Homer “had determined to become a painter,” and by the middle of the Civil War, he was actively exhibiting his oils. The newsroom, then, was just a short stop on this great artist’s journey. Yet the importance of Harper’s to Homer’s oeuvre should not be underestimated. The artist carried the visual strategies that he learned and helped to develop as an illustrator into his work in other mediums. He broadened, but never abandoned the aesthetic of the eyewitness. The “on the spot” sensibility is there in the great Civil War paintings, informing iconic works like Prisoners from the Front and The Brush Harrow that seem at once closely observed scenes and heavily freighted moral allegories (Figs. 1, 8). And we can see traces of the newsman in the watercolors, in Homer’s scrupulous attention to atmospheric effects like the bright and sunny Caribbean light and the distinctive gray of the Cullercoats skies (Figs. 9, 10).

“Strictest veracity,” “unexpected and unconventional candor,” “painting by eye, not by tradition,” “painting what he saw, not what he had been taught to see”: these are some of the terms that scholars over the years have used to praise Homer’s work. They define Homer as a realist, but they also evoke the attributes of a successful artist in the new age of illustrated journalism. As the exhibition at Harvard argues, the artist’s years in the pictorial press were not just an early chapter in a noted career: Harper’s was the crucible that shaped Homer’s realist sensibility. Ultimately, Homer’s work and Homer’s artistic decisions—about what to show and what to hide, when to be direct and when to soften, whose truths to represent and whose to ignore—speak across time, and open up new questions about our own age of image-saturated media, in which truth is sometimes hard to distinguish from trickery.

Winslow Homer: Eyewitness is on view at the Harvard Art Museums to January 5, 2020.

1 The most comprehensive study of Homer’s illustrations is David Tatham, Winslow Homer and the Pictorial Press (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2003). Other major studies include Philip C. Beam, Winslow Homer’s Magazine Engravings (New York: Harper & Row, 1979), and Lloyd Goodrich, The Graphic Art of Winslow Homer (New York: Museum of Graphic Art, 1968). 2 See Joshua Brown’s engaging study of this period, Beyond the Lines: Pictorial Reporting, Everyday Life and the Crisis of Gilded Age America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002). 3 Tatham, Winslow Homer and the Pictorial Press, p. 18. 4 Dana E. Byrd and Frank H. Goodyear III explore the “journalistic possibilities of photography,” and the broader impact of photography on Homer’s work in Dana E. Byrd and Frank H. Goodyear III, Winslow Homer and the Camera: Photography and the Art of Painting (Brunswick, ME; Bowdoin College Museum of Art in association with Yale University Press, 2018). 5 Brown, Beyond the Lines, p. 48. 6 “Affray in Boston” in Harper’s Weekly, vol. 4 (December 15, 1860), p. 787; “Our Artists in the Field. Unrivaled Corps” in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Weekly, vol. 12 (June 1, 1861), p. 33; “The Illustrations” in New York Illustrated News, vol. 6 (May 10, 1862), p. 11. 7 Quoted in Brown, Beyond the Lines, p. 33. 8 In addition to the self-portrait in News from the War, see, for example, “Our Special” in the Life in Camp series of collector’s cards(1864). 9 “Our Artists During the War,” Harper’s Weekly, vol. 9, no. 440 (June 3, 1865), p. 339. 10 For James E. Taylor’s account of his time at the front, see Oliver Jensen, “War Correspondent, 1864: The Sketchbooks of James E. Taylor,” American Heritage, vol.31, no. 5 (August/September 1980), available online at americanheritage.com. 11 “The Progress of Painting in America,” North American Review, vol.124, no. 256 (May 1877), pp. 451–464; p. 458. 12 For a broader discussion of this image, see Peter H. Wood Winslow Homer’s Images of Blacks: The Civil War and Reconstruction Years (Austin: University of Texas Press; 1988), pp. 29–31. 13 Lloyd Goodrich, Winslow Homer (New York: Macmillan for the Whitney Museum, 1944), p. 6. 14 This language is quoted from William Howe Downes, The Life and Works of Winslow Homer (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1911), p. 41, and Lloyd Goodrich, Winslow Homer (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1973), p. 17.

Ethan W. Lasser, formerly the Theodore E. Stebbins Jr. Curator of American Art at the Harvard Art Museums, is John Moors Cabot Chair, Art of the Americas at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. He co-curated Winslow Homer: Eyewitness with Makeda Best and Oliver Wunsch.