The pioneering educational theorist Maria Montessori is known to have said, “It is true that we cannot make a genius.” In that vein, one of the foundational precepts of the American Folk Art Museum, the brainchild of another pioneering woman, early twentieth-century folk art collector and dealer Adele Earnest (1901–1993), is the belief that creative genius is often found among the unschooled and in unexpected places.1 The American Folk Art Museum has always been ahead of its time, championing both the historical and non-traditional work of under-represented artists. Following Earnest’s initial vision, several other women have been key to the museum’s growth and impact as an institution. From Mary Black and Barbara Johnson to Elizabeth Warren, Stacy Hollander, and now Emelie Gevalt, women curators have presented innovative exhibitions and important research to the field. In celebration of the museum’s sixtieth anniversary the sampling shown here of its holdings by women artists highlights the innate, unschooled, and often uncelebrated creative genius that has contributed so much to American visual and material culture.

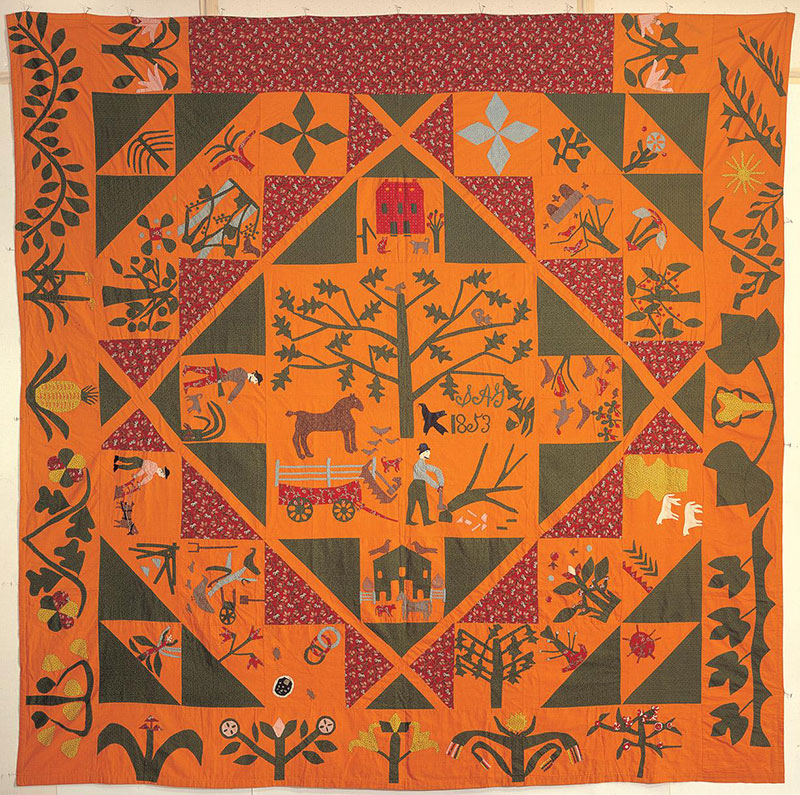

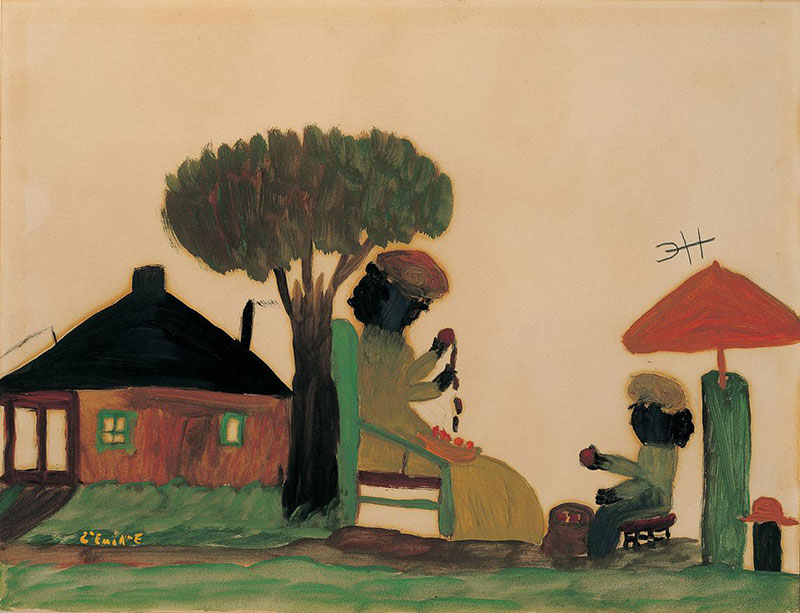

Many of the works by women artists in the museum tell the stories of everyday lives. A pictorial appliqué bedcover made in 1853 by Sarah Ann Garges depicts scenes of daily work on a Pennsylvania farm (Fig. 1). Sarah tells her uplifting story of rural life through a keen sense of color, with dark green designs on a vibrant orange background. A century later, an everyday scene on a mid-twentieth- century Louisiana plantation was depicted by African American artist Clementine Hunter, whose grandparents were enslaved, and whose parents were sharecroppers. She was inspired to paint on found materials while employed as a cook at Melrose Plantation and lived to see her artwork celebrated. In The Apple Paring, painted about 1945, Hunter depicts a mother and child in silhouette seated and peeling fruit while shaded by a tree and a small umbrella (Fig. 2). Both Sarah Garges’s quilt and The Apple Paring reference personal memories of women’s lives, and when viewed in context highlight the parallels and differences in their experiences.

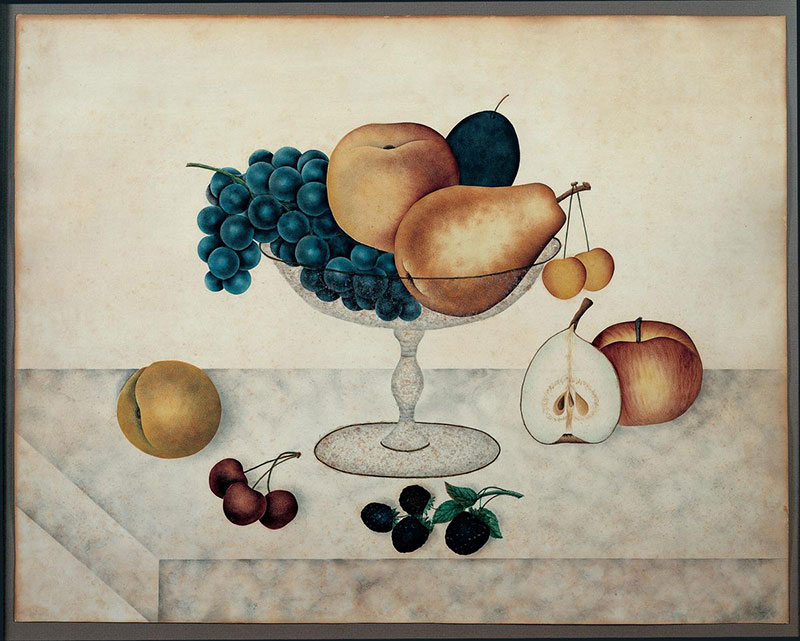

Still lifes in the museum collection highlight the continuum of this traditional genre in folk art and in later self-taught works of art. Fruit in Glass Compote, a highly sensitive theorem painting in watercolor, gouache, and pencil painted about 1895, is one of the few known examples by the New York State artist Emma Jane Cady (Fig. 3). Although her occupation was listed in census records simply as “housework,”2 Cady was clearly a remarkably skilled artist. She embellished the glass compote with mica chips to add an effect of translucency, and heighten interest to her picture. Also drawn with precision and meticulous attention to detail is Bohemian Glass No. 2, painted by Sophy Regensburg in New York City in 1972 (Fig. 6). Regensburg studied art as a hobby late in her life, and executed many still lifes in a deliberately naive style. Her palette was remarkably bold and saturated, and she often included interesting assemblages of decorative arts in her paintings.

Definitions of folk art often include “unschooled” as a qualifier; however, the schoolgirl work produced by young women during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries is a beloved and prolific art genre. In addition to reading and writing, needlework and watercolor painting were important to a young woman’s education in preparation for her roles as a wife, mother, and homemaker. The decoration of wooden boxes and furniture was also popular at young women’s academies.3 A decorated worktable from New Hampshire of about 1819 portrays the State House in Concord (Fig. 4). Government buildings and monuments were common subjects in schoolgirl paintings, as they reflected the artist’s patriotism and reverence for the new American republic. This table would have been proudly displayed in a family’s home to exhibit a daughter’s skill in “female accomplishments.”

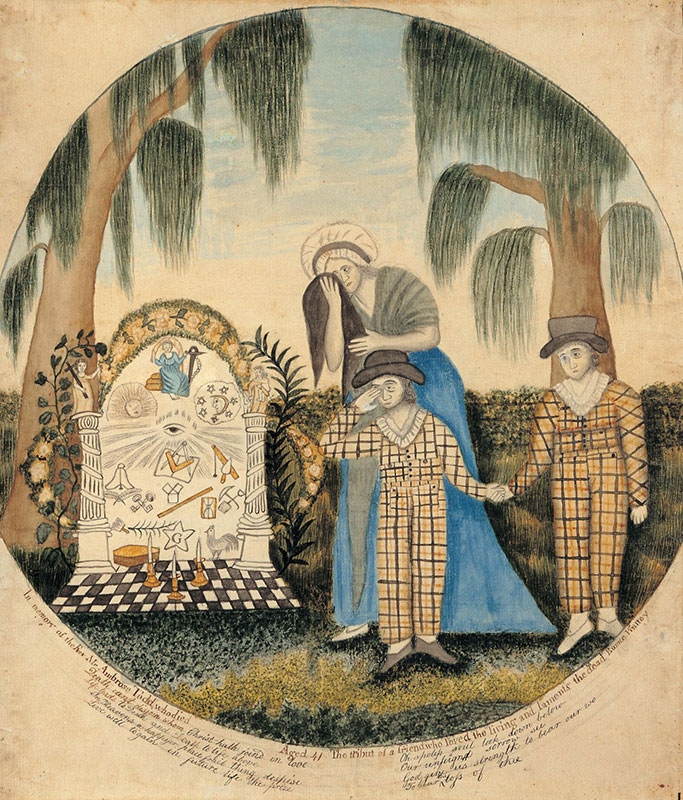

Eunice Pinney produced her known body of work later in her life, rather than as a student at an academy. One of the earliest known American folk artists to work in watercolor, she created works that are unique in style and subject matter, and reflect her personal artistic vision. Pinney was, a “woman of uncommonly extensive reading,”4 and many of her paintings have literary subject matter. Notably modern and independent for her time, she was divorced and remarried, having left her first husband due to his “frequent intoxication” and her fear of being “sick and in constant danger.”5 Her Masonic Mourning Piece for Reverend Ambrose Todd, painted in Connecticut in 1809, is a memorial to a beloved friend (Fig. 5). The incorporation of Masonic imagery in a memorial picture is unusual—and demonstrates yet another way this early nineteenth-century woman strayed from convention.

Unlike Pinney, little is known about Emily Eastman, a woman to whom a group of distinctive watercolors has been attributed. Her whimsical portraits of women feature detailed textile patterns. Although she highlighted fanciful period fashions in all her work, the sensitivity and delicacy of hand exhibited in the museum’s example, Woman in a Veil, elevates it from fashion illustration to soulful portrait (Fig. 9). In an untitled portrait of a fashionable woman by Inez Nathaniel Walker, the subject wears a striped dress with dynamic curving lines; her earrings and patterned hat are carefully depicted using colored pencil, pencil, and crayon (Fig. 8). In search of a better life, like so many other impoverished African Americans of the Great Migration era, Walker moved from South Carolina to Pennsylvania during the 1930s. She began drawing portraits while incarcerated in the 1970s, serving a term for manslaughter after she killed a man who was abusing her. During Walker’s year in prison, she created many portraits, finding solace in her newly discovered artistic practice.

The creative and spiritual worlds of women come together in a group of artworks known as Shaker gift drawings. Formed in the mid-eighteenth century, the Shakers’ utopian and religious communities were based on principles of celibacy, simplicity, and repentance. During the 1840s and 1850s, a time the Shakers called the “New Era,” several women were entranced by what they considered to be spirit messengers, and they were inspired to document these mystical experiences in drawings referred to as “gifts.” A Reward of True Faithfulness From Mother Lucy to Eleanor Potter, made at the community in New Lebanon, New York, in 1848 by Polly Ann (Jane) Reed is inscribed with spirit messages heard by the artist: “Hear me my child, says Mother, while I speak words of truth to you . . . truly you have the gospel to cheer your dreary way” (Fig. 7). Reed incorporated biblical references and symbolic images in watercolor and ink with precision and a calming, meditative balance. A much later work, Three Faces in Lush Landscape, was painted in 1959 by Minnie Evans, another artist who recorded trance-induced visions and dreams in her work (Fig. 12). She once reflected that “In a dream it was shown to me what I have to do, of paintings.”6 Evans was a descendant of enslaved people who originally came from Trinidad and the vibrant celebratory colors and exuberant floral forms in her work are reminiscent of traditional Caribbean Carnival costumes, though the style and subject matter of her work are unique and personal.

Fig. 8. Untitled by Inez Nathaniel Walker (1911–1990), New York City, 1973–1978. Colored pencil, pencil, and crayon on paper mounted on foamcore, 17 ⅞ by 12 inches. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. William G. Webb; photograph by Adam Reich.

Fig. 9. Woman in Veil attributed to Emily Eastman (1804–c.1841), Loudon, New Hampshire, c. 1825. Watercolor and ink on paper, 14 5/8 by 10 ⅝ inches. Esmerian gift; Taylor photograph.

A small number of nineteenth-century women made a living from their artwork. Ruth Whittier Shute, for instance, found success as an itinerant painter who created portraits alone and in collaboration with her physician-turned artist husband. She boldly advertised her services on April 7, 1836, in the Concord New Hampshire Patriot and State Gazette: ”Portrait Painting: Mrs. Shute would inform the ladies and Gentlemen of Concord that she has established herself in the above business.”7 The Shutes found a ready market for her work in female mill workers across New England, including Eliza Gordon, who was employed at a Peterbourgh, New Hampshire, cotton mill (Fig. 10). The Shutes applied gold paper to accentuate Eliza’s jewelry, and painted a dynamic blue-streaked watercolor background that would inspire modern abstract artists a century later. Contemporary studio artist Kathyanne White relies on intuitive inspiration when creating her textile pictures. She works in the traditional medium of quilting, with a modified technique in which she spontaneously places her own hand-dyed cotton textile pieces on a canvas. In Reflection, from 2001, she created a swirling, painterly abstraction with a dramatic blue palette reminiscent of the background of the Shutes’ portrait of Eliza Gordon (Fig. 11). Together these artworks tell the story of women’s roles in textile production in America—from the homespun to the products of textile mills and the artist’s studio.

Fig. 11. Reflection by Kathyanne White (1950–), Prescott, Arizona, 2001. Hand-dyed cotton, 78 by 48 inches. Gift of the artist; Ashworth photograph.

The theme of authentic creative expression runs through all these seemingly disparate but mutually sympathetic works of art united under the umbrella of American folk art. The strategic plan adopted by the American Folk Art Museum in 2020 states that the museum will “integrate the principles of diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion into all aspects of its culture.” A harmonic choir of women’s voices and a variety of life experiences are already represented in this unique collection.

EILEEN M. SMILES is an antiques dealer specializing in American furniture and folk art.

1 See Stacy C. Hollander, “Breaking the Rules of Art: Genius and the Emergence of the Seft-Taught Artist” in Self-Taught Genius: Treasures from the American Folk Art Museum (New York: American Folk Art Museum, 2014), pp. 12–41. 2 Stacy C. Hollander, American Radiance: The Ralph Esmerian Gift to the American Folk Art Museum (New York: Abrams, 2001), p. 501. 3 See Robert Shaw, The Instruction of Young Ladies: Arts from Private Girls’ Schools and Academies in Early America (Cooperstown, NY: New York State Historical Association, 2016), pp. 40–44. 4 Susan Foster, “Couple and Casualty: The Art of Eunice Pinney,” Folk Art, vol. 21, no. 2 (Summer 1996), p. 32. 5 Ibid., p 33. 6 Quoted in “Minnie Evans,” at americanart.si.edu, citing Nina Howell Starr, “The Lost World of Minnie Evans,” Bennington Review, vol. 111, no. 2 (Summer 1969), p. 41. 7 Suzanne Rudnick Payne and Michael R. Payne, “Portraits, Purpose, and Perceptions: Early American folk artists Ruth W. Shute and Samuel A. Shute,” The Magazine ANTIQUES, vol. 188, no. 4 (August 2021), p. 81.