Amid the pale, Grecian mediocrity of Lower Manhattan’s civic center stands a monument of unaccountable excellence, the Tweed Courthouse at 52 Chambers Street. Fully one and a half centuries after William “Boss” Tweed—the most corrupt politician in New York City history—was sent packing in disgrace, he is still so famous for venality that the very architecture of his courthouse seems compromised and even contemptible by association. And yet, in the sedate dignity of its whole and in the perfection of its parts, this one structure surpasses all of its neighbors: City Hall just to its south and the Surrogate Court across the street, as well as the Municipal Building and the New York County Supreme Court, both nearby on Centre Street.

Although initial plans for the building—which now houses the city’s Department of Education—were drawn up in 1859 by an obscure architect named Thomas Little, in 1861 a far more capable man, John Kellum, was engaged to improve the design, and ground was broken later that year. Even though work slowed during the Civil War, the building’s exterior was mostly completed by 1865 and the Court of Appeals moved in two years later. But when Kellum died in 1871 at the age of sixty-one, the building’s southern exposure and most of its interior spaces were still unfinished and they would remain so until 1881, when Leopold Eidlitz completed the work in a very different and even dissonant style.

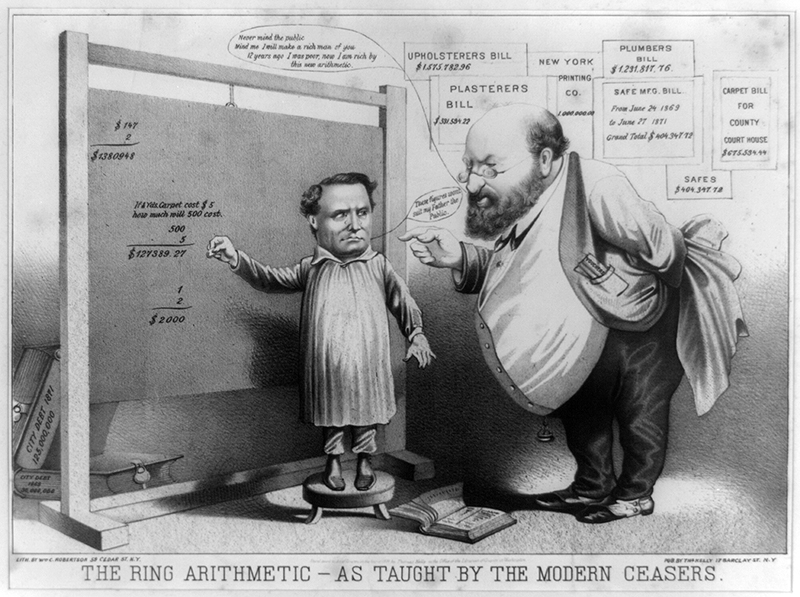

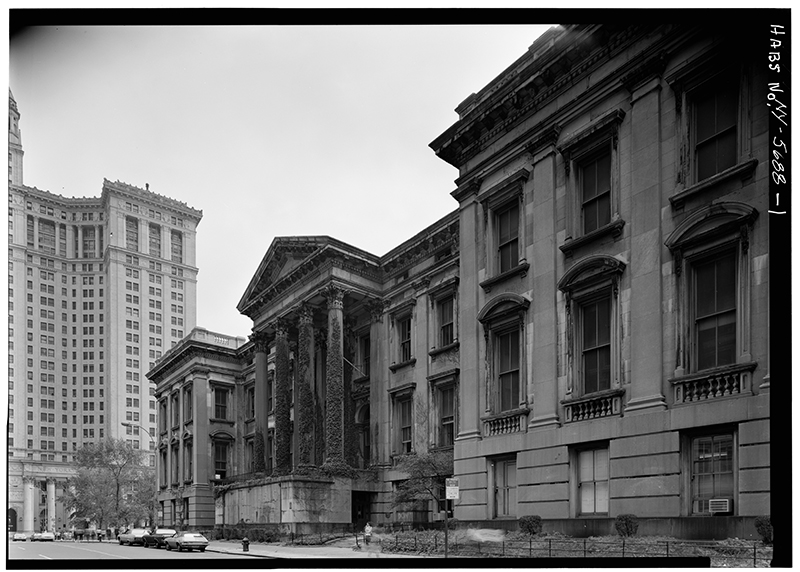

It is part of the charm and notoriety of the courthouse that Tweed, who had inflated construction costs as much as fifty times to line his and his cronies’ pockets, was himself sentenced there in 1873, after being convicted on 204 counts of financial chicanery. And yet, whatever his sins, the courthouse that perpetuates his name is a marvel. Like many of the major public buildings in nineteenth-century America, from the US Capitol to New York’s City Hall, to say nothing of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Museum, the form of the courthouse ultimately derives from Palladio’s Villa Barbaro, its central temple front attached, by means of symmetrical wings, to a pavilion at either end. The entire three-tiered structure— incorporating gleaming Tuckahoe marble— consists of a rusticated podium and two upper stories linked by Doric pilasters in the pavilions and the wings and by Corinthian columns in the central portico. Each of the pavilions, together with both wings and the central entrance, is three bays wide. As with the typical Roman temple front, one enters by ascending a steep flight of steps, on the principle, dear to classicists, that architecture should elevate its occupants and that one should literally rise to engage it. A large classical dome, based on the Capitol in Washington, was designed for the center of the building, but the courthouse has lost little, and may have gained something, by the fact that the dome was never built.

Like most American architects of his day, Kellum was largely self-taught; but his autodidacticism, unlike that of most of his contemporaries, was not awkwardly manifest. Only compare this courthouse with Joseph-Francois Mangin’s City Hall, or even Brooklyn’s Borough Hall (the construction of which Kellum himself oversaw according to the designs of his mentor Gamaliel King), and the difference is obvious. In both of those earlier buildings the massing is dull, while the detailing of the City Hall facade, with its insistent rustication, Corinthian columns and paneled swags, is fussy and inert. Such was the case with so much of New York’s architecture in the first half of the nineteenth century, which looks downright provincial next to the Tweed Courthouse.

Indeed, in no other project did Kellum himself equal the excellence he exhibited here. Surely there is charm and energy in his still extant Ball, Black, and Company Building at 565 Broadway and his Cary Building, down the street from the courthouse at 105 Chambers Street, both inspired by Italian Renaissance models. What those projects lack, however, together with nearly every other contemporary American building—the US Capitol is a stunning exception— is a quality that used to be known as the Grand Manner, a formal concept that Alberti reintroduced into Western architecture in the fifteenth century, and that Donato Bramante, Raphael, and Michelangelo bodied forth in the first quarter of the sixteenth. It is a quality that, according to the domi nant narratives of architectural history, was fostered in North America by Richard Morris Hunt, the first American to graduate from the École des Beaux Arts, near the end of the nineteenth century. How remarkable, then, that, through his own genius, John Kellum somehow managed to achieve it decades earlier in the Tweed Courthouse.

The outstanding aesthetic quality of the Grand Manner is less its imaginative energy than the perfection of its parts and the harmony of their combination. At the Tweed Courthouse we sense its presence in the majestic, cubic dimensions of its lateral pavilions no less than in the linteled windows on the top floor, bracketed with volutes and the thinnest of pilastered strips. Take any of the renowned American monuments from the end of the century, whether by Hunt himself or by such disciples as Stanford White and Whitney Warren (whose firm designed Grand Central Terminal), and you will find no window surrounds that surpass, and few that equal, those that Kellum invented for the facade of the Tweed Courthouse.

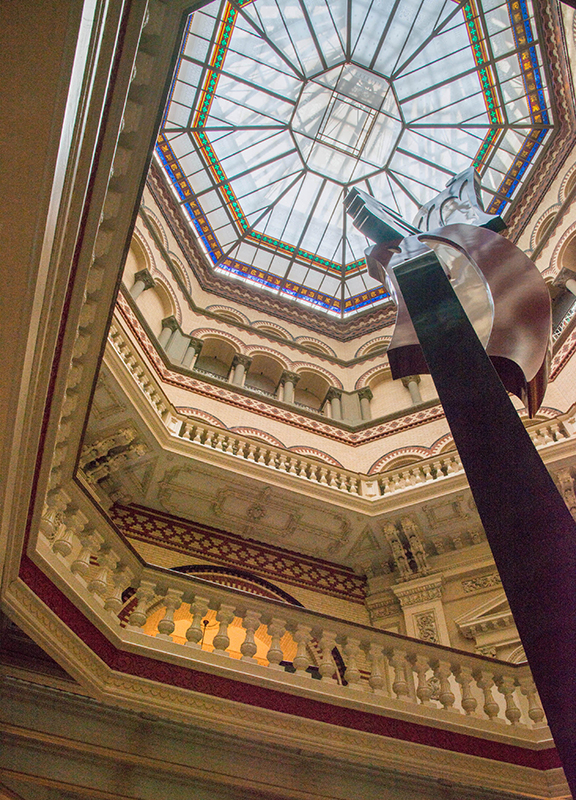

After Kellum died in 1871, Leopold Eidlitz brought a new architectural vocabulary to the courthouse. Born in Prague in 1823, Eidlitz arrived in America at the age of twenty. He brought with him a thorough familiarity with the dominant European style of the mid-nineteenth century, the Rundbogenstil or roundarch style, sometimes known as neo-Romanesque. Identifiable by its strong, medieval-looking arches, this style defines Eidlitz’s work on the State House in Albany, New York, as well as in Saint George’s Episcopal Church in Manhattan. And it also appears, somewhat incongruously, in the southern exposure of the Tweed Courthouse, with its overly ornate Byzantine arches, as well as in the building’s central polychrome rotunda and its assorted state rooms. Even the brightly tiled floors exhibit the sort of orientalist richness that was so typical of the time and so contrary to the monochromatic grandeur of Kellum’s facade along Chambers Street.

For most of its history, almost from the moment of its completion, the Tweed Courthouse has been an object of undeserved derision. One critic, writing in the New York Times on April 29, 1877, complained with some justice that Eidlitz’s additions were “cheap and tawdry in comparison with [Kellum’s] elaborate finishing and classic exterior.” But respect for the latter’s contribution as well was short-lived. Scarcely a decade after the building’s completion, there were calls for it to be razed to the ground in 1891, and ten years later, a very different Times critic wrote that “the Tweed Court House, as an ugly monument of fraud and municipal disgrace, should be razed.” A long list of Gotham’s magistrates agreed, among them Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia and his urban planner Robert Moses in the 1930s and Mayor Abraham Beame in 1974. Around that time Ada Louise Huxtable, the eminent architecture critic of the Times, observed that the building “has been so universally repudiated for its unsavory associations that it is probably too hot a political potato for the Landmarks Commission.” Indeed, despite its remarkable survival to this day, the building suffered a terrible act of official vandalism in 1940, when the great stepped entrance along Chambers Street was amputated, thus destroying that essential concept of ascent and forcing visitors henceforth to enter through the basement.

Only after its designation as a landmark in 1984 did New Yorkers begin to esteem this urban treasure in their midst. And only with the completion, in December 2001, of a full renovation campaign (which also restored the front steps) was the true beauty of the Tweed Courthouse finally revealed. The force of this reassessment is suggested in the claim of Ed Koch, who served as mayor from 1978 to 1989, that “[the Tweed Courthouse] is probably one of the top ten architectural gems of city buildings.” But even that appraisal falls short. The Tweed Courthouse may well be the finest classical building, if not the finest building in any style, ever to rise over the drab bedrock of Manhattan.