The images reproduced here are digital prints from Alinder’s glass-plate negatives, now in the collection of the Upplandsmuseet in Uppsala, Sweden. Photographs courtesy of Dewi Lewis Publishing, Stockport, England.

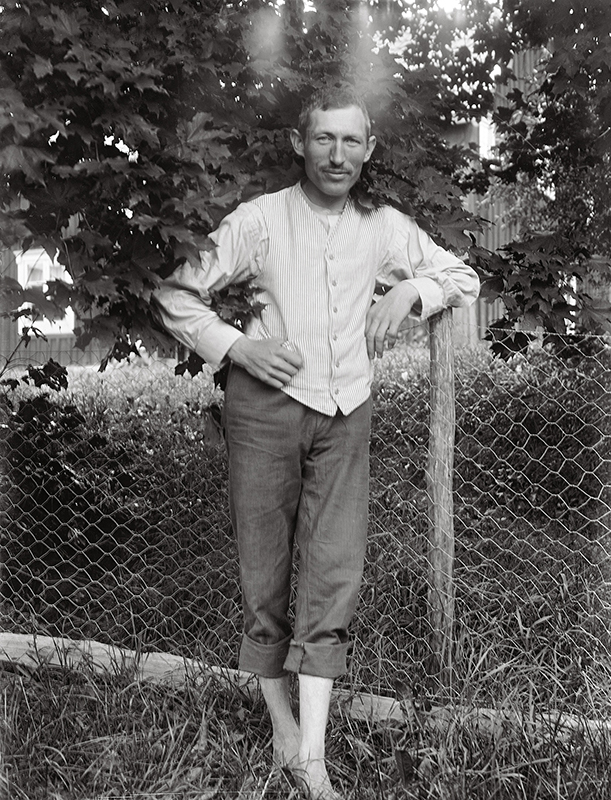

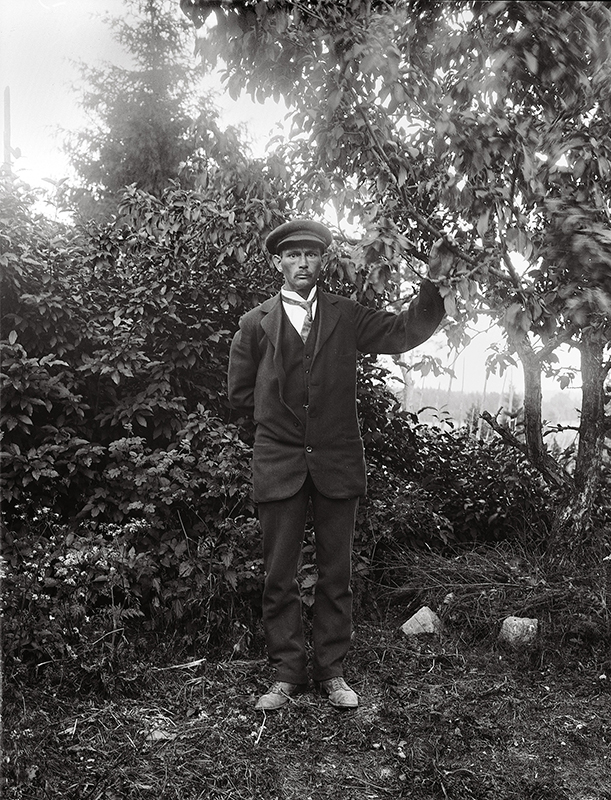

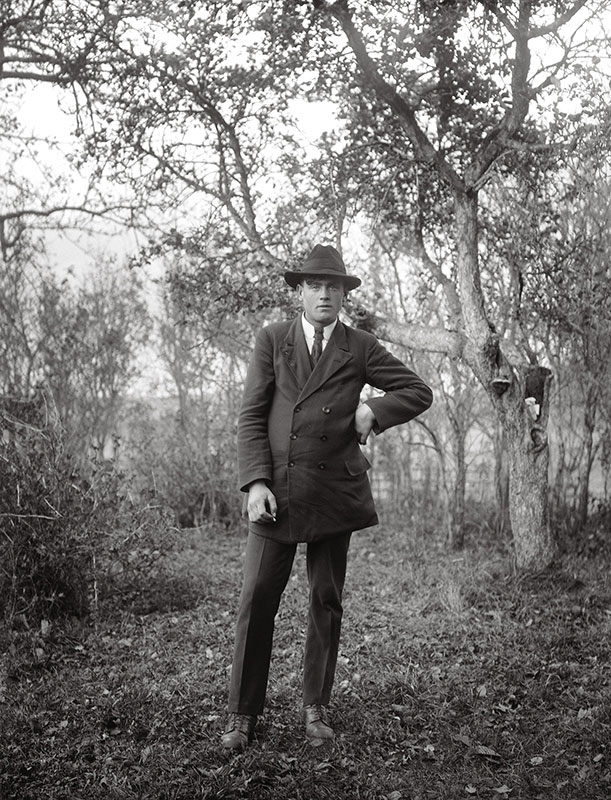

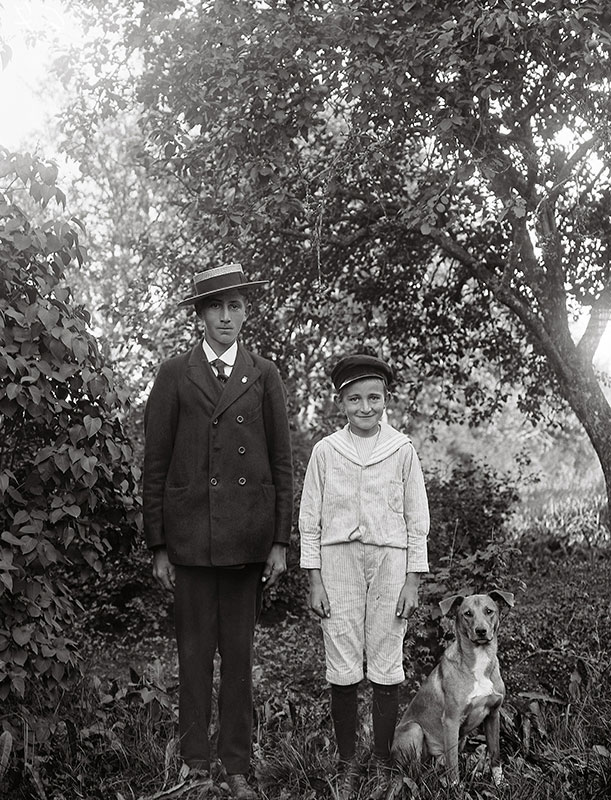

More than a century ago, John Alinder portrayed the villagers of Sävasta, in the Swedish province of Uppland, where he ran a shop and worked as a photographer. His black-and-white prints are suffused with the shimmering light of the Swedish summer. And the carefree spirit that we associate with that season also seems to be expressed in the poses—with a twinkle in the eye—and in the happiness that the people display in many pictures. Their faith in their own existence is so contagious that we feel exhilarated when we look at them.

Alone, in pairs or in groups, the people stand facing the photographer’s camera. He used a camera with large-format negatives. After exposure and development of the negatives, he placed them in direct contact with a special photo paper in a frame under glass and exposed them to sunlight. After fixing, rinsing, and drying, the images were ready. The black-and-white prints have the same format as the negatives, retaining all their information. The motif is rendered with rich and finely nuanced greyscales, extraordinary definition and a wealth of detail that we scarcely find in today’s photographs. These properties permit a close-up study of the prints and thereby open the door to a whole universe.

John Alinder took most of his portraits during the warm season in a shady place in his garden. With the glass-plate camera he could only photograph using a tripod, and the large format together with the low sensitivity of the film material required long exposure times. When the picture was taken, the photographer stood beside or behind his camera while the model was still, looking into the camera lens. As a result of these circumstances, the people were very conscious that they were being photographed. While some appear to have gradually forgotten about the camera, others posed deliberately for the photographer. But they all, children and adults from the different social strata of the village, are self-aware as they stand in front of his camera. Despite the distance in time, the photographs appear unmediated and accessible.

We also notice how calm and secure in themselves the people in these pictures seem to be. It is particularly moving to observe that they show affection and openness to the photographer, testifying to their familiarity and trust. The subjects are fully aware that there is something special about being photographed, they have put on their best clothes and brought along their favorite animals and objects that become part of the staging in front of the camera. Here the photographer gives them space, embedding them in the composition so that they are a part of the cultural landscape that is visible in the background. The spatiality of the images opens up the photographs for our memories and associations.

The pictures reflect the subjects’ relationship to the photographer, but it is the photographer’s actions that give the images their profoundly human character. We can only speculate as to whether his aim in taking the pictures was to formulate a social community that was typical of the time, going beyond the documentary presentation of the villagers. John Alinder’s photographs allow us to arrive at personal and disparate views and interpretations. Whether separately or together, they give us a reading that literally makes the value of life visible.

The article is excerpted and adapted from John Alinder: Portraits 1910–32, published in collaboration with the Upplandsmuseet and Landskrona Foto, Sweden, by Dewi Lewis Publishing.

THOMAS WESKI is one of Germany’s most highly regarded curators and writers about photography. Since 2015 he has been curator at the Foundation for Photography and Media Art with the Michael Schmidt Archive in Berlin.