In Jan van Kessel’s Noah’s Family Assembling Animals before the Ark, the antediluvian world is presented as Earth in need of a hyper-taxonomy, rather than the biblical drama of destruction. Pairs of parrots and pheasants huddle onto branches, as though caged within an aviary, and leopards and lions tussle in the foreground. Livestock, in their drudgery and commonality, are shepherded toward the Ark, their backs turned to us. For the seventeenth-century viewer, the attraction was in the exotic, such as the speckled gray horse and the ostrich, who draw the eye in through their verticality. This painting, alongside nearly seventy-five prints, paintings, anatomical drawings, and artifacts, is among the fanciful works on display in Little Beasts: Art, Wonder, and the Natural World, opening on May 18 at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

Predating the divorce of ars and scientia through the refinement of Enlightenment thinking, these works by sixteenth- and seventeenth-century European artists, most notably the Flemings, Joris and Jacob Hoefnagel, and Jan van Kessel, present a final hurrah for the playful, obsessive nature of the naturalist illustrator who lived between the boundaries of artist and scientist. The exhibition bridges this tension through the whimsical illustrations found within book painting and beyond. In concert with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, art is presented alongside taxidermy. Interactive elements, such as magnifying glasses and take-home nature journals, invite the visitor to a slower, methodological meditation on observation.

The exhibition is divided into three sections. The first, a rare presentation of Joris Hoefnagel’s Four Elements series (the copy owned by the National Gallery, once in the possession of Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor), portable Kunstkammern, each containing more than two hundred watercolors bound into a book devoted to a different classical element.

The four books will have their pages turned three times during the show, with a breathtaking total of sixteen plates on display. Of particular note are Hoefnagel’s treatment of wings in Ignis (Fire), his tome dedicated to insects. Real dragonfly wings, scales tattered and lost to history, are delicately applied onto jewel-like painted bodies, allowing comparison with the artist’s close study of butterflies and moths created with watercolor alone.

The second section concerns the dissemination of natural historical ideas through printmaking (with a special focus on engravings and etchings), which brought together art collectors, naturalists, and those in between. Jacob Hoefnagel, son of Joris, followed in his father’s footsteps as a miniaturist and a painter of naturalia. A selection of engravings from his Archetypa studiaque patris Georgii Hoefnagelii, expands on his father’s work to include fruits, flowers, and vegetables as marginalia for the insect’s world.

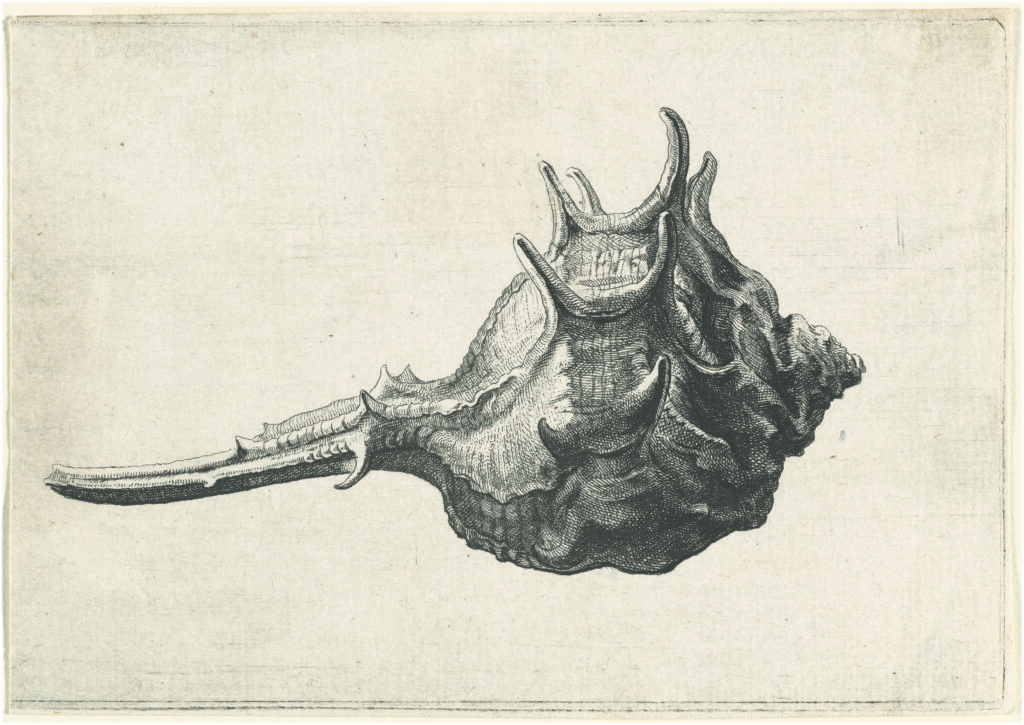

From outside Antwerp, etchings such as the prolific Wenceslaus Hollar’s portrayal of the spiraling spikes of a conch or Teodoro Filippo di Liagno’s heron skeleton from his Animal Skeletons series, showcase the underlying memento mori embodied in the study of the living. The collaboration between the two Washington museums, the first in their history, allows for these vibrant prints to be compared with taxidermied specimens, ranging from a mantis shrimp to an impressively intact Indian peafowl peacock, to a plucky woodchuck paired with a depiction of another, plump and satiated after a dinner of plums, in a mixed-medium gouache and graphite image by Italian artist Jacopo Ligozzi.

Focused on Jan van Kessel, the third section displays his paintings and prints alongside a selection of taxidermied animals that inspired the works. Of particular interest is a digital interactive kiosk re-creating the cabinets on which van Kessel’s small-format oil-on-copper paintings were usually displayed, probably echoing the natural specimens within. Using a surviving suite of the artist’s paintings on loan from Oak Spring Garden Library in Upperville, Virginia, the cabinet highlights the emerging demand for luxury goods in the seventeenth century. These cabinet paintings, a triumph in trompe l’œil, elevated the cabinet from function to fantasy. This domestication of the little beast, within the confines of the decorative object, brings us back to man’s dominion over the animals. Furs from the wilderness are preserved, likenesses of its denizens ensnared in paper menageries—all giving evidence of our desperation to keep them contained and under our thumb, forever.

—Cindy Hernandez

Little Beasts: Art, Wonder,and the Natural World • National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC • May 18 to November 2 • nga.gov