With an incoming director and the institution’s first two curators of color, the reopening museum is in capable new hands.

One of New York’s most cherished museums, the Frick Collection resides in the Fifth Avenue Beaux Arts mansion commissioned from architects Carrère and Hastings by industrialist Henry Clay

Frick, who collected principally European fine and decorative arts from the Renaissance to the nineteenth century. It has a reputation for staying largely the same, with iconic works by Rembrandt, Titian, Vermeer, and Turner along with Sèvres porcelains, fine furniture, and other treasures, remaining largely in their customary places over the ninety years since the opening of the museum, which remains a bastion of tranquility even as the world transforms dizzyingly around it. But on April 17, the museum threw open its doors after its own transformation: a five-year, $220 million restoration and expansion overseen by architect Annabelle Selldorf that yields 30 percent more gallery space, including in the second-floor rooms where the Fricks once lived, which had long served as office space.

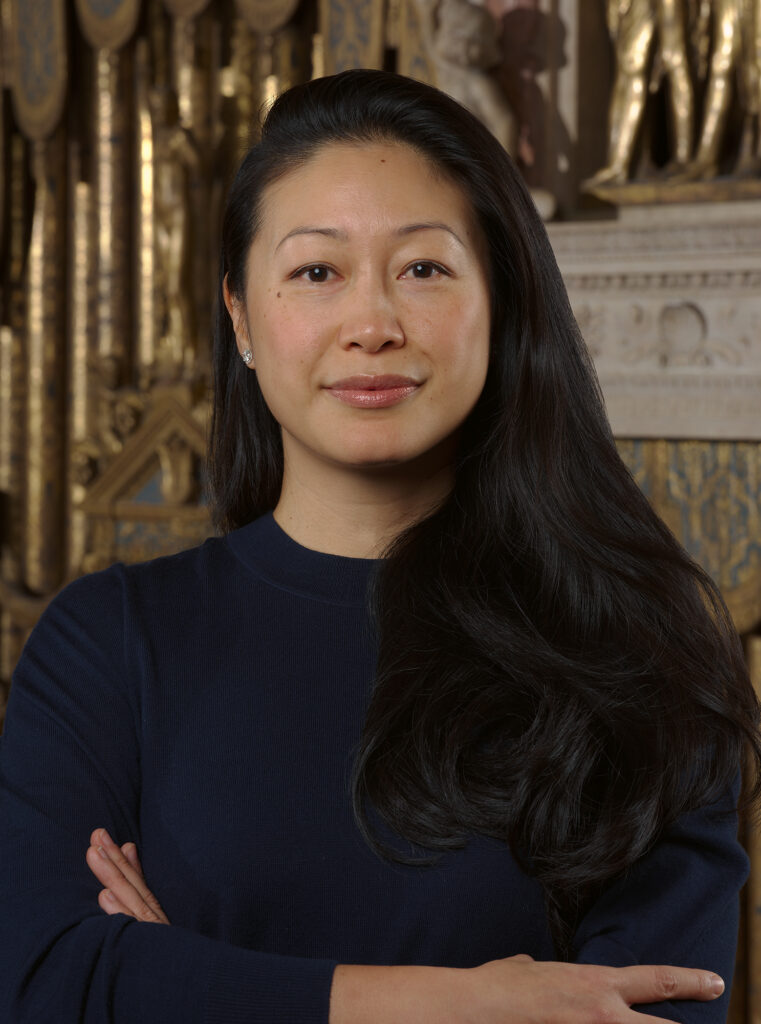

Other firsts include a public café and a dedicated education center. With all this change come a new director, Axel Rüger—he took the reins just weeks before the renovation was unveiled to the press in March—and, in Aimee Ng and Marie-Laure Buku Pongo, two relatively new curators. They rank, respectively, as the museum’s first and second curators of color, and, along with deputy director and chief curator Xavier F. Salomon, they are bringing fresh ideas to a staid and storied institution.

“Everything has to change,” said Salomon at the press preview, “for everything to remain the same.”

Ng was hired as associate curator after guest-curating a Frick exhibition; later promoted to curator, she co-curated the installation of the museum’s holdings at the Frick Madison, its temporary home in the Whitney Museum’s former building, the brutalist masterpiece by Marcel Breuer. There, the museum successfully juxtaposed contemporary artists alongside the Old Masters. And the museum continues its engagement with the artists of today: in the newly installed Frick, ceramic sculptures in the form of flowers and other flora by Ukrainian artist Vladimir Kanevsky appear throughout the galleries, echoing floral displays from when the museum opened in 1935.

Perhaps counterintuitively, as Ng and Salomon explained in interviews in their sunny third-floor offices, some of the museum’s new strides look back to the years when the family lived in the mansion. For example, a popular suite of works by French rococo painter François Boucher, which had been installed on the first floor for public accessibility when the museum opened, was returned to the second floor, to what was Frick’s wife, Adelaide’s, boudoir.

“It changed the room,” Ng said. The relocation of the Bouchers into Breuer’s brutalist surrounds altered visitors’ view of the collection, she noted, and their reinstallation in the original Frick building has “changed the way the Boucher room feels. Adelaide Frick had a private area that was so opulent, and for a woman we know so little about, it brings more of her spirit and identity into the experience of the house.”

Salomon explained that another room devoted to enamels and one devoted to Italian paintings on gold grounds also nod to the ways that works were installed in the family’s day. Looking after the museum’s storied holdings in decorative arts, including some startling new displays, is Buku Pongo. Just the second decorative arts curator in Frick history, she was promoted in 2024 to associate curator after signing on beginning in 2021 as assistant curator. The Brussels native brings experience earned at such institutions as France’s Palace of Versailles and New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The delicacy of the fragile porcelains she oversees provide a perfect contrast to the steely character of the museum’s founder. The Frick is, like many institutions of its time, born of contradictions: it is a place of respite and beauty that was funded by an exploitative robber baron. Anarchist Alexander Berkman even attempted to assassinate Frick, shooting him twice. Salomon makes no attempt to downplay the source of Frick’s money: in fact, he keeps on his desk a piece of coal from Frick’s native Pittsburgh and a hunk of the iron with which steel is made. “Our salaries still come from that,” he says he points out to staff, to whom, like some besuited Santa Claus, he has distributed pieces of Pennsylvania coal.

As America barrels into another Gilded Age, many have asked whether the robber barons of today might muster anything like Frick’s philanthropic spirit. Salomon has no illusions on that front. “It is very disappointing,” he said, “that there is a class in this country that does not follow the footsteps of generosity and open-mindedness of previous generations, where with great wealth came great responsibility in terms of helping other people through hospitals, music halls, museums, and zoos. I hope I’m wrong, but that seems to have changed, and it impoverishes this country.”

The likes of Frick and Andrew Carnegie were imperfect men, he acknowledges, but they left a great legacy. And despite the contradictions, the renewed and expanded Frick Collection will carry that legacy into the museum’s second ninety years in fine style. And who knows? Maybe the revamped Frick will inspire one of today’s robber barons to follow suit.

BRIAN BOUCHER is a New-York based writer whose work has appeared in the New York Times, Playboy, New York Magazine, Frieze, Cultured, Art in America, and ARTnews.