A young artist retraces the museum excursions of his childhood and what led to the rebirth of his love for the arts.

I come from a long and spirited line of artists; in my family some form of creativity is the expectation. My great-grandfather, Meville Humbert, created needlepoints of modernist paintings as a hobby. His daughter, my grandmother, Betty Estersohn, was an abstract expressionist painter and early video documentarian. Her son, my father, Pieter, is a photographer and author of books about history, architecture, and design.

He is a master of light, forever chasing the right moment to press the shutter. In our family there are also many cousins who are musicians or painters; creativity runs rampant in our DNA, so it is ingrained in us at a young age to have a deep interest in the arts. Sadly, my grandmother passed away when I was only two years old, but even as a small child I used the art materials she left behind, often channeling her sense of color and composition. The photograph illustrated above of my father’s office, which also serves as our family art room in Red Hook, New York, depicts four generations of art created by my family.

As a child, I had the rare and privileged experience of frequently traveling with my father, whose work as a photographer took us across the world. Together, we visited over eighty-seven cities, seventeen US states, twenty-four countries, and four continents. These trips were not your typical childhood vacations. Instead of amusement parks, beaches, and resorts, my father took me to museums and historic landmarks. We went to hundreds of unique places, probably thousands by now. For the most part these were not leisurely trips. They were journeys, educational pilgrimages.

Like many children, I was impatient. I had no positive feelings about going to yet another museum. The last thing I wanted to do was stand in front of another ancient tapestry or oil painting from the 1500s. I was far more interested in video games and running around than in Renaissance artworks or ancient ruins. I remember walking hastily through entire exhibitions, glancing briefly at the works while my father exasperatedly tried to slow me down and explain why they mattered. My usual response was to whine, complain, or just keep walking, eager for each place on his agenda to be behind us. I was young and too restless to understand the depth and value of what I was

being shown.

Back then, I also did not understand why my father insisted on buying secondhand furniture. He would drag me to flea markets, antiques shops, rug shops, and auctions, excited by dusty wooden chairs and old classical pier tables. I did not get it. Why would anyone want old things when shiny, new ones existed? To me,they looked like worn out furniture from someone else’s life. I couldn’t understand enjoying an aesthetic that was not ultra-modern.

But, as I grew older, something shifted. I now find myself drawn to older aesthetics, the charm of imperfection, of craftsmanship, and of the stories behind older items. I have even started building my own small collection of antiques and curiosities, including watches, vintage rings and pins, clothing, paintings, posters, and other things that have caught my eye. One of my favorite pieces is an Israeli bowl that is sixteen hundred years old. I am always on the lookout, slowly and selectively choosing pieces that speak to me. And in this process, I have learned to love what I once rolled my eyes at.

It took time and a massive amount of maturing, but I have come to truly value what my family exposed me to. The context given to me growing up helped immensely in my academic life, particularly in history classes. It was not

just that I knew more about art and history than most of my peers, it was that I saw the world differently. I valued context. I asked questions. I noticed details in architecture, lighting, and design that most people had overlooked.

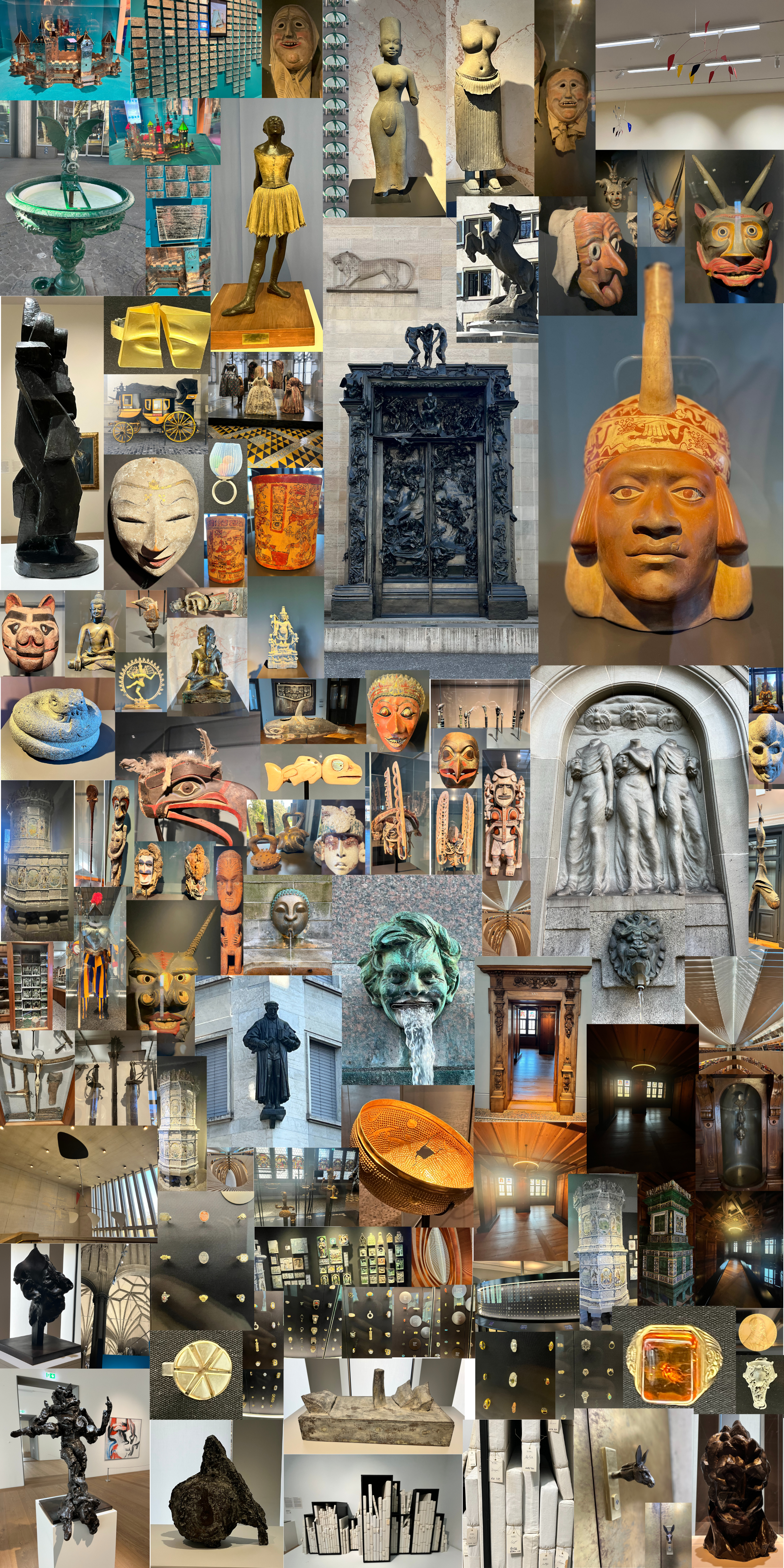

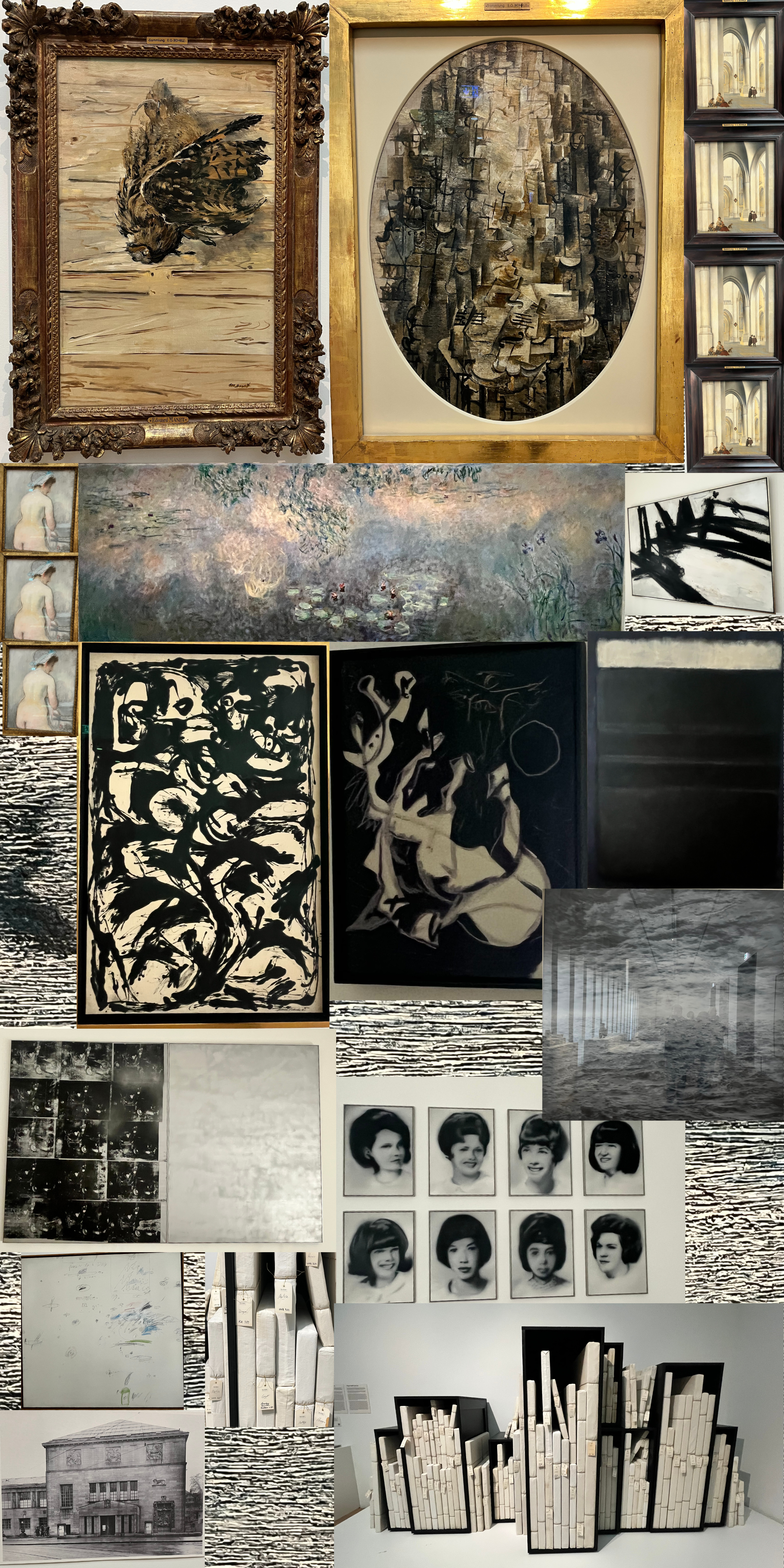

Ironically, when I travel alone now, I find myself doing one of the things I dreaded the most growing up: exploring museums. This became especially clear during my recent semester abroad in Bologna, Italy, where I studied at Dickinson College’s K. Robert Nilsson Center for European Studies. In just eighteen weeks, I visited twelve countries,

twenty-five cities (Florence three times), and explored a total of 235 museums, historic buildings, and architectural landmarks, all with a student discount price applied!

I walked the halls of the Musée Rodin in Paris, Kunsthaus Zürich, the Glyptothek in Munich, the Spanish Synagogue in Prague, Berlin’s thought-provoking Jewish Museum, the Victorian Baths in Malta, the Palazzo Reale di Torino, Via XX Settembre in Genoa, the Roman Forum, Dante’s Tomb in Ravenna, and the Estense Castle in Ferrara, to name just some. I stood where important moments in history occurred, where creatives dreamed, and where the best art in the world is kept. I went to museums that focused on dozens of differing subjects, from graffiti to war, design to classical art, fashion to architecture, and even museums of the sciences. During these trips I walked from one museum to the next historically significant place, with twenty-three days in which I walked more than ten miles, one day even covering seventeen miles.

Each step, each train ride, each ticket stub represented a deeper dive into the past, into my own relationship with beauty and meaning. These experiences not only helped me get my daily steps in, but reignited the curiosity my father had subtly instilled in me for years. My semester in Bologna will always mark an important point of reflection in my life. These trips matured me. I stayed at amazing places and sketchy ones too—like the hostel with holes the size of small children in the floor. I got to meet interesting people traveling Europe and had the chance to hear their stories. The semester also rekindled a love for art that I hadn’t acted on since I was much younger.

Growing up, I loved painting, drawing, and building. I even sold my first painting at thirteen years old, after it was published in Architectural Digest. While in high school I had taken a few art classes, but my passion for creating had somewhat receded. As a sophomore at Dickinson, it was reawakened in a sculpture class taught by Professor Anthony Cervino, a class that was hands-on, messy, and liberating. In it, my creativity and interest in art started to take root again.

While in Europe, I picked up my pencils and pens and started drawing once more. This renewed passion led me to a decision: going into my senior year of college, in September, I will pursue a minor in art and art history, to accompany my double major in law and policy and political science.

Children may fight and complain about going to museums and historic places, they might even briefly hate the adults who take them, but I think it is crucial to keep encouraging them anyway. Enforcing these exposures will give them a leg up in life, and force them to think differently from their peers, it will widen their perspectives and broaden

their horizons. You might even get a “thank you” one day.