A suggested menu for something called a “New England Family Dinner” reads as follows:

Dutch Spiced Flank Steak

Roast Sweet Potatoes

Jerusalem Artichokes

Mulled Cider

Cranberry Nut Pudding

Just to the left of that tempting roster is an observation, together with a piece of timeless decorating advice: “The past is a rich treasure trove from which we can borrow all the marvelously romantic ways and means to turn our own homes into deeply satisfying environments.” It reads like something from a 1930s society magazine, in the throes of the colonial revival. In fact, it’s from The Treasury of Ethan Allen American Traditional Interiors catalogue, dating to 1976. This particular section, devoted to the “Heirloom” line of Ethan Allen furniture, has a tagline more prescient than the authors ever intended, echoing the phrase coined by literary critic Van Wyck Brooks in 1918: “the usable past.” If the past is, after all, a treasure trove, what are we waiting for?

That anyone could imagine a stone farmhouse without central heating, during a war against the British Empire, as “marvelously romantic” speaks to the power of a consciously constructed past. In the worlds of interior design and collecting, this fantasy has had a cultural power that extends far beyond furniture. But that’s precisely what Ethan Allen was selling in 1976: a past that could be used, rather than accurately recalled.

That’s one of the most useful things about commemorating an event from long ago: no one alive can remember it, thus all interpretations are at least plausible. With all due reverence to the founding fathers, any anniversary celebrations will be entirely about us, that is, those of us who are around to mark the occasion. And, as in any democratic endeavor, the reviews will be mixed. So it was in 1976, when cultural institutions, historic house museums and villages, and sites run by the National Parks Service, along with the manufacturers of t-shirts, buttons, and banners, together celebrated the two hundredth birthday of the United States of America.

The Bicentennial landed at the doorstep of a nation still reeling from upheavals: political assassinations, the Watergate scandal, the resignation of President Nixon, and the catastrophic American withdrawal from Vietnam. Historian Marc Stein, author of the forthcoming book Bicentennial: A Revolutionary History of the 1970s, notes that people tended to react in one of two ways: “Many political leaders and bicentennial planners saw in the Bicentennial a chance to ‘turn the page.’ Counter-Bicentennial activists, including those who called for a ‘Bicentennial without colonies,’ also wanted to turn the page, but they tended to see Vietnam and Watergate as further proof that it was time to take seriously the nation’s founding rhetorical commitments to anti-colonialism, democracy, equality, and justice.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, among the most well-received events was the widely lauded Bicentennial iteration of Operation Sail (or “OpSail”), which brought an impressive fleet of 228 tall ships and hundreds of support vessels into New York Harbor. It was poetic and conveniently viewable at a distance; about six million people from New York and New Jersey watched the ships come in. At the time, President Gerald Ford described it as “the greatest Fourth of July any of us will ever see.” Elsewhere in New York City, and a bit farther south on Philadelphia’s Independence Mall, other hotly anticipated and high-profile Bicentennial programming was met with a mix of curiosity, enthusiasm, and bafflement that in retrospect seems entirely appropriate to the era. That July Fourth may indeed have been the greatest ever, but it was also profoundly postmodern.

Charles and Ray Eames, for example, designed what turned out to be their final big collaborative project together (Charles died in 1978) in The World of Franklin & Jefferson—a massive visual and informational celebration of the two founders, which traveled from Paris to Warsaw and London before opening at the Metropolitan Museum in March 1976. This exhibition was part of an even more comprehensive project undertaken by the Eameses at the Met at the behest of then-director Thomas Hoving, who engaged the pair to reimagine the museum’s operations for the computer age.

Big anniversaries were on the collective brains of the couple, the institution, and the country: as the United States headed for its two hundredth birthday in 1976, Hoving commissioned the Eameses to devise an architectural, visual, and informational reimagining of the museum at the dawn of the institution’s “second century.” The result was a proposal in two parts: a physical model of the museum presented to Hoving, which showed how the institution could offer visitors “hospitality” in the inimitable Eames style, by encouraging them to interact with a timeline of art history on interactive terminals and use the computers to devise customized tours; and a short film, Metropolitan Overview, 1975, which showed the reimagined museum in action. Attractive renderings show visitors in mid-1970s clothing enjoying gallery displays packed with objects and flanked by a very prominent visual timeline on one wall. A voiceover intones, “some real things taken from storage” were to be “set among supporting material,” which is to say, posters and informational graphics.

Metropolitan Overview, 1975 was classic Eames: reminiscent of the charming, tech-y whimsy of their multi-channel visual display from the 1964–1965 World’s Fair; engagingly busy, and decidedly not minimalist. The visual and informational approach—lots of data, some genuine articles, and copious signage occupying seven thousand square feet of gallery space—was also in keeping with the corporate personality of the exhibition sponsor, longtime Eames partner IBM. The project sought to create for visitors a palpable sense of the texture and rhythm of daily life that Franklin and Jefferson inhabited; but it also presented the two men as inventive polymaths, whose technical innovations, in some small but consequential way, set the United States on course to become a technocratic superpower.

The exhibition’s handsome catalogue resembles a colonial sampler; there’s no negative space. Each page is packed with reproductions of early American portraits and the things that furnished their world: almanacs, Rittenhouse clocks, clay pipes, a chest that may have played a role at the Boston Tea Party, the writing desk upon which Jefferson penned the Declaration of Independence, printer’s tools, a medal of the Society of the Cincinnati. Men’s fancy dress from the late eighteenth century, grand portraits, a girandole mirror, and a spinning wheel conjured a sense of technology and style, if not time and place. And a taxidermied bison from Chicago’s Field Museum along with various animal skins from creatures of the mountain West signaled the journey of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, with invaluable guidance from the young Shoshone woman known to history as Sacagawea; the impetus for their journey had been the Louisiana Purchase, spearheaded by Jefferson.

Visitors loved it—critics, not so much. London-based features reporter Hugh Hebert described the exhibition in the pages of The Guardian as “7,500 feet of brilliantly devised, grossly packaged confusion.” Hilton Kramer was less effusive in the New York Times of March 5, 1976, suggesting in his review that it needed only “a brass band and a couple of hot‐dog stands to make the atmosphere of a Fourth of July celebration complete.” But putting aside the celebratory aesthetic of the show, which even he conceded was bound to make the exhibition a hit, Kramer zeroed in on the fact that The World of Franklin & Jefferson was more like an informational display than an art exhibition. “It is not the spirit of Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson that we see in this slick display, but the spirit of modern advertising,” he wrote, “which is obliged to reduce every experience and every value to an easily identifiable sign and an easily digestible slogan.”

Whether the exhibition succeeded in its aims of educating and inspiring the public is hard to know for sure; the world of the founding fathers is long gone, but then so is the world of Thomas Hoving and Charles and Ray Eames.

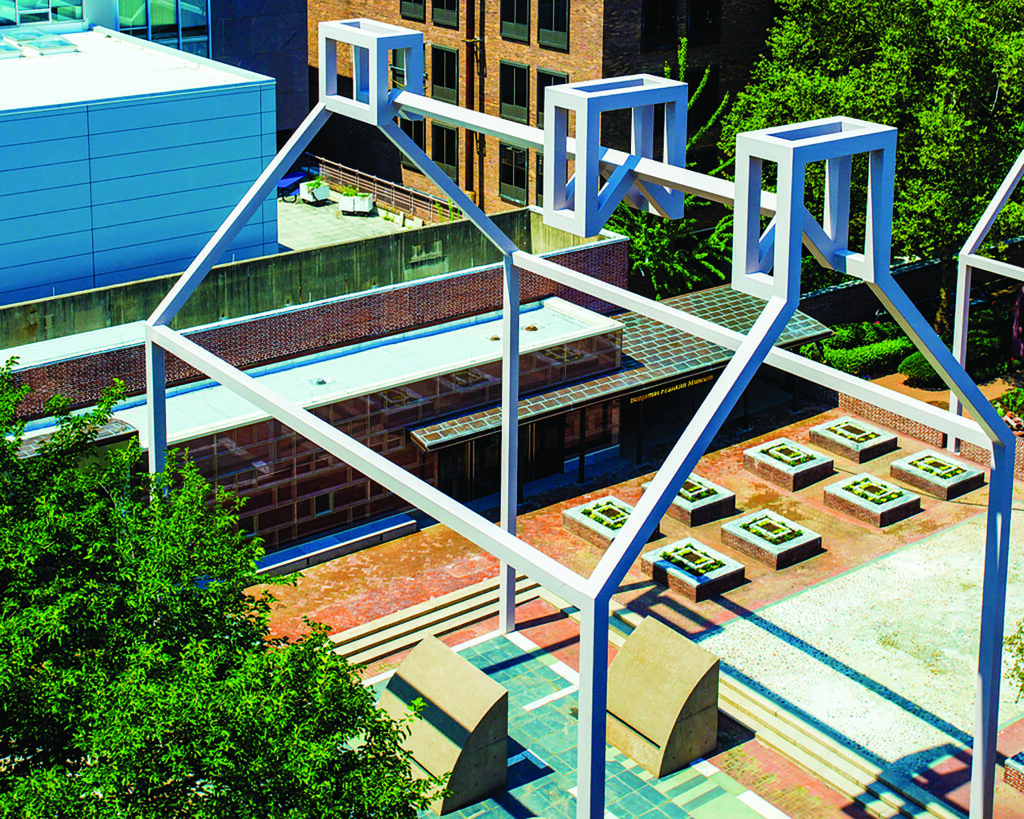

Strangely, the Eameses were not the only legends of mid-century American design to attempt a link between 1776 and 1976, nor the only ones who did so using the latest audio and visual technology. Venturi, Scott Brown, and Associates, with their deep ties to Philadelphia, were selected to design Franklin Court, a memorial to Benjamin Franklin in the heart of the city, just in time for the Bicentennial celebrations. Some of their interventions, like the austerely elegant “Ghost Houses,” remain: white frames delineating the former dimensions of five eighteenth-century dwellings near Independence Hall.

Poet and Haverford College professor Thomas Devaney, whose 2020 film Bicentennial City captures the fraught complexity of Philadelphia’s role in the celebrations of 1976, remembers an enchantingly weird element of the celebratory landscape from that year: “One of my most beloved installations [was the one that] Venturi Scott Brown did at the Franklin House,” he says. “You went down this ramp and there were neon and mirrors, and it was kind of like a disco entrance. There was a phone bank with about thirty phones, and you could call one of the founders in the middle of a sunken set piece of the Framers at Independence Hall that lit up when someone spoke.”

This surreal scene was inside the Benjamin Franklin Underground Museum, described by WHYY reporter Sue Landers—who also remembers visiting it as a child—as “the National Park Service’s disco-era celebration of Franklin . . . a place trapped in time, a collection of corded phones and neon lights. It was awesome.” In 2013 the National Park Service undertook a major renovation of the site, over Venturi and Scott Brown’s objections; the Underground Museum wasn’t moved or mothballed, it was simply “lost,” according to an article that ran that year in Hidden City Philadelphia. So the neon signage that proclaimed Benjamin Franklin as “INVENTOR, STATESMAN, AUTHOR”; mirrors that invited visitors to contemplate Franklin’s multifaceted nature and their own; the rows and rows of Princess telephones that visitors could use to hear commentary on Franklin, are now mostly gone. During her own visit in 2013, Landers learned that while much of the structure of the original Underground Museum had been discarded, certain elements like a model of a typical eighteenth-century house were now safely stored at the Second Bank of the United States, and the figurines from the exhibit devoted to Franklin’s diplomacy, “Franklin and the World Stage,” were clustered in boxes, still wearing their fancy dress.

I would suggest interpreting these endeavors—along with the grandeur of Operation Sail, and the proliferation of souvenirs that Yale American Studies Professor Jesse Lemisch has called “Bicentennial Schlock”—as valuable evidence from their time rather than failed exhibitions. It may be the case that Venturi and Scott Brown and the Eameses didn’t effectively transport visitors to the moment of the American Revolution, but to do this is impossible, as any Ethan Allen copywriter, or fan of period fiction, museum period rooms, and historic villages will know all too well. Re-creations are inevitably products of their own times, and reflect the preoccupations, hopes, and anxieties of the moment of their creation, not the long-gone era to which they refer.

In a sense, the Eames and Venturi and Scott Brown installations did perfectly capture the spirit of a historical period: the 1970s, as the country and its cultural institutions were wrestling with narratives about itself that it didn’t want to hear, the dawn of postmodernism, and the proliferation of new technologies that allowed visitors to personalize their experience of museums. In 1976, both the leaders and the citizens of the United States were understandably of two minds about what story they wanted to tell about themselves in celebration of their Bicentennial. Military failure, domestic discord, economic stagnation, and cultural tumult made the idea of settling on one national narrative complicated at best.

The postmodern turn of the mid-twentieth century, in which a general skepticism about objective truth made grand narratives seem obsolete, arrived just in time to give the designers tasked with helping the country navigate its Bicentennial an escape hatch. The expanding possibilities of computers and audio-visual technology like Acoustiguide in museum settings offered visitors throughout the 1970s a preview of the media and informational landscape that was to come; while broadcasting and print media still provided dominant narratives, the multiplicity of telephones, didactic information in a dizzying array of physical formats, and the sheer quantity of artifacts on view in these Bicentennial installations presaged the increasingly customized and self-curated ways we experience museums today.

Now we explore collections through our phones and on our computers before we ever set foot in a museum building, we can watch interviews with artists and exhibition tours on social media, we can listen to curators and critics talk about art and design on podcasts, and—perhaps in unintentional tribute to the founding fathers’ array of Princess telephones in Venturi Scott Brown’s exhibition—we can document both ourselves and the objects that mean the most to us with the same communications device we use to navigate a gallery floor plan or find the operating hours of the museum cafe. The world of Venturi, Scott Brown, and the Eameses has much to teach us about our present moment and our recent history. What better time than our own semi-sesquicentennial moment to spend some time in the neon glow of a very useful past indeed?

SARAH ARCHER is the author of several books including The Midcentury Kitchen, Midcentury Christmas, and Catland: The Soft Power of Cat Culture in Japan. Her writing can be found in the New York Times, T Magazine, Architectural Digest, Untapped, and other outlets.