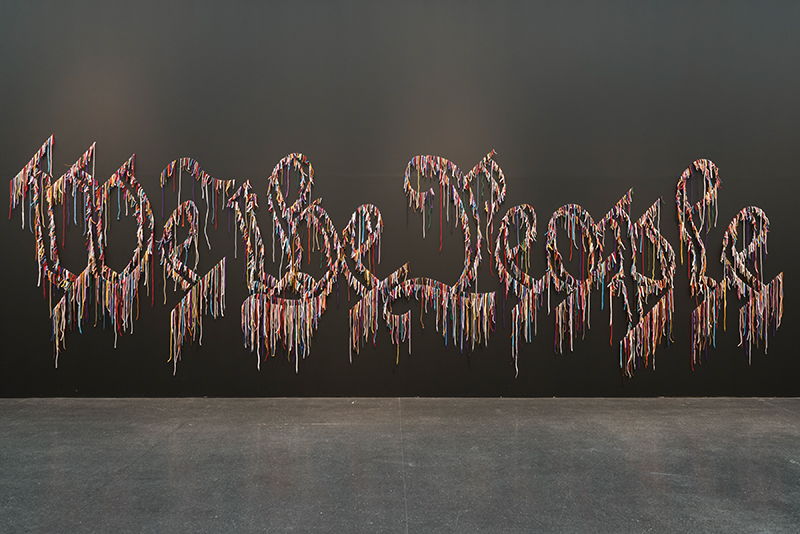

Step into the galleries at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, and you will immediately encounter, in giant letters, the phrase We the People. In this work by the artist Nari Ward, the famous beginning to the preamble of the US Constitution is executed entirely with used shoelaces, inserted one by one into small holes drilled into the wall. The laces could refer, obliquely, to Black street culture—the cult of the basketball sneaker, perhaps, or impromptu memorials made by throwing shoes over power lines. But because of their previous history of use, they also amount to a sort of community portrait. The curators at Crystal Bridges mirrored that idea in artworks installed on the opposite wall, drawn from every part of the permanent collection, as well as from other museums. George Washington is here, as is Rosie the Riveter (in Norman Rockwell’s famous 1943 depiction), along with Native American painter Fritz Scholder’s pop-inflected painting Super Indian, and the Black civil rights activist Hugh Hurd, dapper in a green jacket and matching socks, in an affecting portrayal by Alice Neel.

As recently as 2018, when Ward’s work was installed with these paintings, it took courage and conviction to so explicitly address questions of diversity and inclusion. In most American museums, the overriding method has long been to let art “speak for itself,” and for curators to remain discreetly offstage, even though that supposedly neutral approach is anything but. Nearly all museum collections bear the deep imprint of past inequity. We simply reinstate those dynamics when we hang acknowledged “masterpieces”—mostly by white men—and stand back in admiration.

While there has been growing awareness of these facts for years, it is only thanks to the Black Lives Matter protests that swept the USA this summer that many institutions are finally facing up to them. A long overdue reckoning with racism has arrived; fortunately, it cannot be avoided. What will happen next is hard to predict, however, because the issues are so multivalent, complex, and overwhelming in scale. Compounding the problem is the lack of diversity in museum staffs and trustee boards, which will take a generation at least to correct.

In the meantime, scholars are stepping up and doing the work. The leading institution is the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which opened on the National Mall in Washington in 2016. Its acclaimed displays have been an inspiration to other museums nationwide. More recent examples of restorative research include the Black Craftspeople Digital Archive, founded by Tiffany Momon (a recent guest on TMA’s Curious Objects podcast). By gathering object-based and documentary evidence, Momon aims to make a single research gateway into the complex history of Black craftspeople. She places particular emphasis on telling a “spatial story,” focusing on particular locales to build a collective account of the transient and precarious lives led by African American artisans, both enslaved and free. (Momon’s research is also included in the newest issue of the MESDA Journal, published by the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts, which presents nine case studies in African American material culture.)

As important as these focused efforts are, for the big picture to change, all museums must change their priorities. Here, too, there are encouraging signs of change, beginning right at the top: the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Met has hardly been a bastion of progress on these matters—in June, fifteen staff members sent an open letter describing “a deeply rooted logic of white supremacy and culture of systemic racism at our institution.” Director Max Hollein responded, effectively agreeing with them, and promising to do better.

What might that look like? Programming can’t be the whole answer, of course, but exhibitions and permanent displays are a crucial part of the picture. Adrienne Spinozzi, the Met’s organizing curator for “Southern Make”: The Enslaved Potters of Edgefield, South Carolina (a working title; the show is currently planned for 2022), sees her institution as committed to “presenting more works by people of color and artists and makers who have heretofore been marginalized or underrepresented in our galleries.”

“Southern Make” has been in development since 2017, but it has definitely been affected by the Black Lives Matter movement: “It is impossible to be working with objects that were made by enslaved African American potters,” Spinozzi says, “and not be motivated by the recent protests and calls to action against systemic racism and police brutality, lasting ills of a society built on the institution of slavery.” As it happens, Edgefield pottery is a particularly rich opportunity to engage with this difficult history. The face jugs so strongly associated with the region are thought by some researchers to reflect the transmission of West African spiritual traditions. Later, however, the typology was picked up by white potters in the South. It’s not always possible to determine the racial identity of a maker, so a given pot could be an expression of Black cultural perseverance, or conversely, an act of white cultural appropriation.

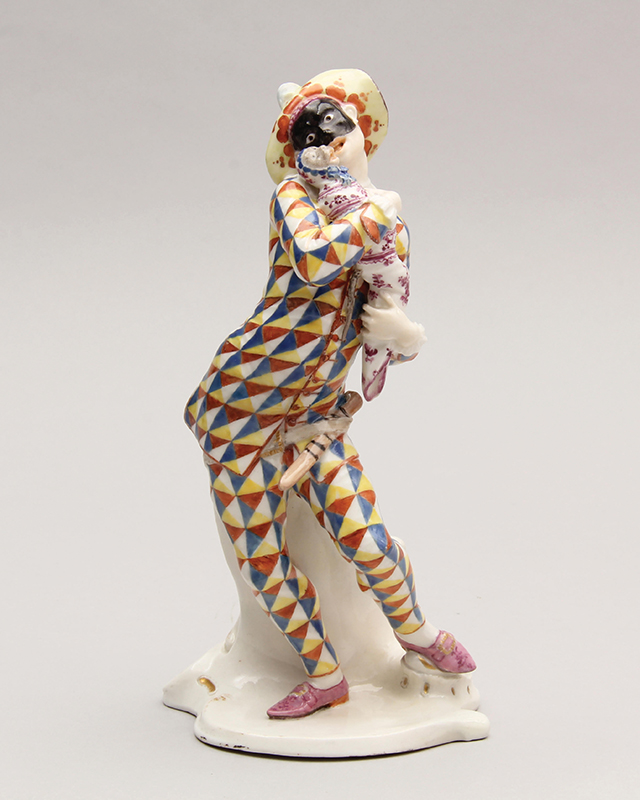

Throughout the project, Spinozzi has yielded her conventional curatorial authority over such difficult matters; the exhibition team is working with a group of ceramic historians, archaeologists, and scholars of the African diaspora and slavery studies (including Tiffany Momon). Up in Toronto, the Gardiner Museum—which specializes in ceramics—is taking a similar approach to an equally tricky topic: the interpretation of eighteenthcentury porcelain figurines depicting Harlequin, the commedia dell’arte protagonist. What does this have to do with questions of racism? Thereby hangs a tale. It began about eighteen months ago, when a woman of color, attending the museum as part of a community partnership initiative, noticed two figurines of Harlequin, and asked if they were in racist blackface. The programming manager leading the tour replied that she would look into it.

Soon the matter was presented to Sequoia Miller, newly arrived as the Gardiner’s chief curator. The first thing he did was turn the figurines around, so that they faced away from the visitor—“a peculiar but elegant solution,” as he puts it, that registered their potentially problematic nature through a moment of intentional dissonance. Then he got to work. He knew that the Harlequins actually predated the advent of blackface, as that term is usually applied, by more than a century. By consulting with external specialists in theater history, though, he found that there were connections hiding in plain sight: paintings of Harlequin in which the character’s facial features are indeed strongly racialized; and a direct line of influence extending forward from the caricature-based humor of Italian street comedy, through British pantomime, to the American minstrel shows in which blackface become so notoriously prevalent.

Are the masked Harlequin figures offensive? How about a face jug by a white potter? Embracing diversity means embracing the complicatedness of such questions, which admit of no simple answers. At the time of writing, both Spinozzi and Miller—both of whom are white—continue to involve others in their decision-making process. “Broader engagement, consultation, and participation are crucial,” Miller says, beginning in his case with a question posed by a member of the public, which could have been easily (and wrongly) dismissed. How curators interpret figural ceramics from long ago—or, indeed, walls full of portrait paintings—may seem of modest importance, compared to the seismic shifts in public consciousness that have occurred this year. But it’s of such building blocks that a new, egalitarian edifice will be built. It’s a project we will all need to work on, together.