Necessity, as the saying goes, is the mother of invention. When the galleries of early American art—loosely defined as works produced between 1650 and 1850—at the Philadelphia Museum of Art reopen this spring, many will realize just how great the need was to rethink the museum’s display of its celebrated collection.

To many minds, a reassessment may have been long overdue. When I arrived at the museum in 2001 as an assistant curator in American art, talk was already swirling about the possibilities for reinstalling the collection. But trustees and strategic planners understood that simply buffing up the old spaces would not be enough. The collection—and its potential to tell a history of art in early America—deserved not only a new, more clearly organized presentation, but also to be easily accessible to visitors—ideally directly off at least one of the main entrances. But first, our iconic grand dame of a building needed some updates—and reorganization of the supporting spaces. Storage was moved off site. The Perelman Building—formerly home to the Fidelity Mutual Life Insurance Company and designed by the architecture firm responsible for the PMA1—was opened to house additional galleries, administrative and curatorial offices, the costume and textiles and prints, drawings, and photographs collections, the library and archives, and several conservation studios. A parking garage was tucked into the side of the natural rise—the Fairmount—on which the museum is perched. And a spacious art-handling facility was built on the south side of the building.

In the fall of 2007, then-PMA director Anne d’Harnoncourt chose Los Angeles–based architect Frank Gehry to mastermind a plan for the renewal, reorganization, and expansion of the main building. She looked to his work at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California, as the type of efficient ordering she sought for the PMA. Soon after d’Harnoncourt and Gehry began their collaboration, she died—a sudden and untimely blow that was soon followed by the 2008 financial crash.

The museum’s next director, Timothy Rub— a historian of architecture, among other subjects— deftly prioritized needs and phased the building’s transformation, working with the museum’s trustees and with president and chief operating officer Gail Harrity to define the “Core Project.” This called for creating a large forum space beneath the Great Stair Hall, reworking the West Entrance and the adjacent Lenfest Hall, reopening the North Entrance (which had been closed for more than a half century), and recapturing spaces on the first floor originally designed for administrative offices as light-filled galleries for the display of the museum’s collections of American art and contemporary art.2 By 2013, architects, planners, construction project managers, and numerous staff had focused on their Herculean tasks, and the museum’s generous trustees committed their time, talents, and treasure to execute the vision they had embraced.

Planning for the American galleries began in earnest in 2016. The curatorial team was well prepared by decades of experience at the PMA, and inspired by tremendous gifts of large collections, such as that of board chair Leslie Miller and her husband, Richard Worley, and the late collector and benefactor Robert L. McNeil Jr. (whose name adorns the new wing), as well as the generous patrons who supported monumental purchases such as Charles Willson Peale’s Portrait of Yarrow Mamout (Mamoud Yarrow); the Fox and the Grapes dressing table (see p. 66); Thomas Fletcher’s masterpiece in silver, the Maxwell Vase (Fig. 12); and Thomas Doughty’s paired views of the Fairmount Waterworks. Our own research and installation trials and successes that had been measured in a parade of exhibitions—An Eakins Masterpiece Restored: Seeing The Gross Clinic Anew (2010–2011); Journeys to New Worlds: Spanish and Portuguese Colonial Art from the Roberta and Richard Huber Collection (2013); Audubon to Warhol: The Art of American Still Life (2015); Classical Splendor: Painted Furniture for a Grand Philadelphia House (2016)—and in collections catalogues, from the Peale family paintings (by Carol E. Soltis, 2017), to American silver (by Beatrice B. Garvan and David L. Barquist, 2019), and my American furniture (2020).

Confounded by the meandering floorplan of the 1976 design of the American galleries, Rub worked with Gehry and his associates with the goal of clarifying the spaces for a more straightforward presentation. The plan that he shared with us in the summer of 2016 centered on four main galleries—each with entry points to the light-filled hallway that looks onto the East Terrace with its dramatic views down the “Rocky” steps toward Philadelphia’s downtown and our iconic City Hall.

Early on, the early American art curators—led by Kathleen A. Foster, with David Barquist, Carol Soltis, and myself—determined that the narrative we sought to share through the art collection would be presented in a traditional, roughly chronological manner, but that it would tell the history of American art in new, broader, and more inclusive ways. Simply put: more accurately than before. Curatorial assistant Rosalie Hooper organized trips to museums and historic sites around the region to help broaden our scope. We read voraciously on the subjects of how to represent the indigenous people whose lands William Penn and others took; how to address slavery and enslaved people, whose contributions to early American art are known to have existed but are so often anonymous; how to present women as the significant contributors that they were; and how to show the range and depth of art at the museum— furniture, paintings, silver, pewter, iron, porcelain, earthenware, samplers, fraktur, prints, and silhouettes— without having cluttered platforms and cases. With eyes wide and energy high, we redoubled our efforts to study our collection and find the songs that our art could sing best.

Working with a scale model of the galleries and artworks, we met twice a week for entire afternoons over the summer of 2018 (Fig. 5). Guiding us were Hooper, collections project manager John Vick, our exhibition design team led by Jack Schlechter and Jorge Galvan, as well as the education department’s interpretation team, which now includes Hooper. We would “do” one gallery and then the adjacent one, settling on the art and the interpretation. When a new idea or concept floated among us, we would find ourselves emptying the model and starting again. On our walks from our offices in the Perelman Building over to the model in the main building, we often wondered whether, when finished, we would end up just where we had begun.

While our presentation showcases a museum collection rich in the arts of early Philadelphia and southeastern Pennsylvania, material from this culturally diverse region is displayed alongside selected works of art from areas that had social, economic, and cultural connections to Philadelphia, such as the Caribbean, the Portuguese and Spanish colonies in Latin America, South Carolina, New York, Newport, and Boston.

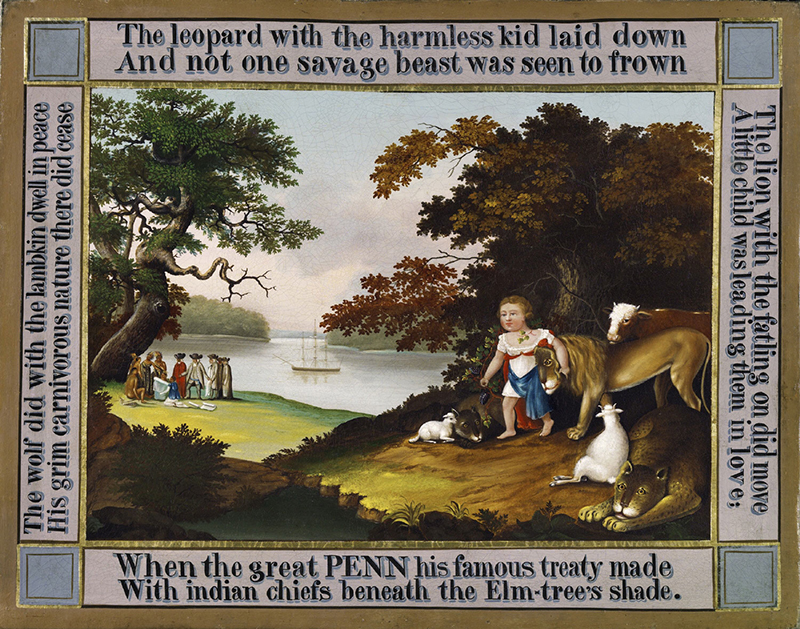

Visitors to the American galleries will first encounter a display that puts in context William Penn’s acquisition of the land from the Lenape. Taking center stage inside the first gallery, titled “American Encounters,” are Gustavus Hesselius’s portraits of the Lenape chiefs Tishcohan and Lapowinsa from 1735 and a wampum belt said to date to 1682, all on loan from the Board of Trustees of the Atwater Kent Museum (Philadelphia History Museum), the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, and the City of Philadelphia.

In the same gallery, the regal, Catholic grandeur of Spanish colonial paintings contrasts with the more understated high chest and dressing table made by the Quaker joiner John Head of Philadelphia. We also connect the economic and social stories of colonial America, since both the Spanish and British empires were rooted in a mercantile system dependent on conquering the indigenous people of the Americas and enslaving Africans. The subdued and enslaved worked in sites from Potosí in Bolivia to the Caribbean and northward from Savannah to Philadelphia to Boston—mining silver, building roads and cities, cultivating sugar and other crops, distilling rum, felling mahogany, manning ships, as well as working alongside white artisans in urban shops.

For me, this history was revealed in Caribbean Quakers (1972) by the Wilmington, Delaware, author Harriet Frorer Durham (1924–1991), which outlines the trade networks of the Quakers of colonial Pennsylvania who operated plantations worked by enslaved Africans in the Caribbean. Their products made Philadelphia and its merchants prosperous— a fact also evident in my study of Philadelphia’s probate inventories. That Pennsylvanians—including the culturally dominant Quakers—benefitted from and exploited enslaved Africans is a story not often told. A goal throughout the galleries is to expose and acknowledge the contributions of enslaved Africans—their labor; their agrarian knowledge applied, for instance, to the cultivation of rice and indigo; their skill at the iron foundries and forges; and their talents as artisans in the making of furniture, silver, and porcelain (see Figs. 1, 3).

The presentation in the second gallery, titled “Global Connections,” stems from a motto we adopted early on: globalism is not new! Silver, upholstery textiles (such as those reproduced on a Boston easy chair), mahogany high chests from Newport and Charleston, blue-and-white earthenware mimicking Chinese porcelain—all demonstrate the global trade, well established by 1700, that connected Europe, Asia, Africa, and the Americas. On loan from the Dietrich American Foundation are Henry Popple’s giant composite map of British North America, a high chest made in Boston by John Brocas and painted in imitation of Asian lacquer, and a table made in Boston and topped with slate inside an elaborate marquetry frame. An interactive display shows the route the slate-andmarquetry top traveled from Continental Europe (probably Switzerland), to London, and then to Boston, where it was added to a locally made base.3

The “Loyalty and Independence” gallery showcases conflicting notions of dependence on and independence from the European artistic traditions of London, Paris, Lisbon, Dublin, and elsewhere. Visitors are greeted by the only portrait of Philadelphia sitters— the rebellious Thomas and Sarah Morris Mifflin— by the Boston artist John Singleton Copley, who was himself an infamous loyalist. The grandly scaled and freshly conserved double portrait was painted in 1774 when Thomas, at the age of twenty-nine, was sent to Boston to rouse that city’s elite toward the cause of independence. His wife shows her allegiances by weaving a decorative upholstery tape on a loom rather than importing it from Britain. In the same way, rather than exporting valuable white clay (or kaolin) for porcelain to be made in Europe, colonial Americans made porcelain at home—in Charleston, South Carolina, and, by 1770, in Philadelphia. Colonial artists often ventured to Europe to achieve greatness, and a display will feature the neoclassical painting Agrippina Returning with the Ashes of Germanicus by Benjamin West, as well as classical landscapes by the lesser-known Philadelphia native John Taylor (Fig. 11). The social significance and stylistic variations of chairs of the period is seen in our wall of chairs, four over four, inspired by Charles F. Montgomery’s display at the Yale University Art Gallery.

The section titled “Pennsylvania Crossroads” examines interrelationships between the arts of Philadelphia and those of outlying farmlands north and west of the city. The works of art made by English, Welsh, Scottish, and, by the 1750s, an increasing number of first-generation German émigrés, in these areas rivaled those of their urban counterparts. In our display, clocks from Philadelphia and Lancaster—the largest inland city in North America in 1776—will be paired side by side. Sampler traditions are introduced along with the burgeoning art of fraktur drawings. And, finally, no display proves the artisanal virtuosity in Philadelphia and surrounding counties more profoundly than the juxtaposition of the Fox and the Grapes high chest and dressing table—fresh from conservation and happily contextualized with the help of an architectural molding on the wall—with the sulfur-inlaid Kleiderschrank made for George Huber in 1779.

One of the questions we faced was how to pace the messages we wanted to impart in the galleries. How should we draw attention to those we felt were most important? Do we talk about women as artists and patrons in one place, or weave their stories throughout? Do we have one gallery dedicated to the art of the Pennsylvania Germans or display it throughout? And with the histories of Black artists and artisans so often invisible, what can we do to call attention to the ones we do know? Ultimately, we landed on a two-pronged approach: we wove stories throughout and created areas that concentrated on those poignant histories.

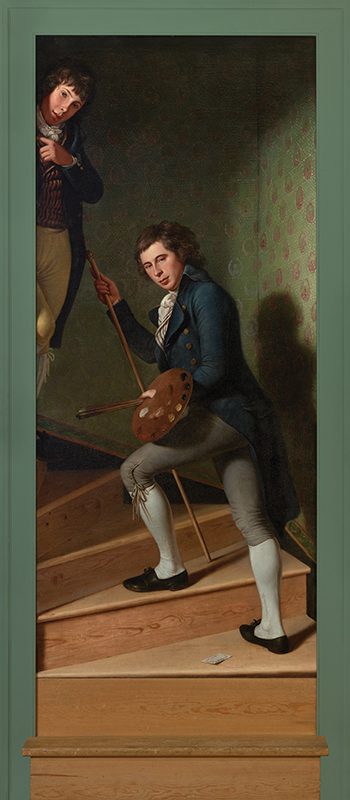

Seen from the hallway, Charles Willson Peale’s Staircase Group (Portrait of Raphaelle Peale and Titian Ramsay Peale I) (Fig. 13) lures visitors into the third group of galleries, which opens with “A Family of Artists.” After an extensive examination and conservation treatment, this much-loved painting—the ultimate trompe l’oeil—is set into the wall rather than projecting from it, with a new, more correct frame and step. Deciphering the evidence, curator Carol Soltis and conservator Lucia Bay suggest this is the positioning that maximizes its impact and best reproduces its original arrangement in Peale’s studio. C. W. Peale’s Portrait of Yarrow Mamout and silhouettes by Moses Williams, who was enslaved and then freed by the Peales, introduce the discussion of free and enslaved artists and artisans in the Philadelphia of the early republic.

Since the early eighteenth century, Philadelphia aspired to be the “Athens of America”—and the British-born architect B. Henry Latrobe, painter Gilbert Stuart, the city’s silversmiths, and others helped the city achieve that goal. The advent of the neoclassical style was well timed to meet the moment of the new republic, and art in the “Splendor in a New Nation” gallery, dating from the 1790s through the 1810s, demonstrates that. An H-shaped set of walls in the center of the gallery provides space for two installations—one re-creating the painted walls and furniture Latrobe planned with Mary Waln for the house he designed for her and her husband, merchant William Waln. On the opposite side, a newly recreated fringed and tasseled canopy tops a French bedstead with a history of ownership by Joseph Bonaparte, the exiled king of Spain and elder brother of Napoleon. Thomas Birch’s View from Point Breeze on the Delaware, showing the grounds of Bonaparte’s grand villa outside Bordentown, New Jersey, hangs in the elegantly wallpapered niche.

The last galleries in the enfilade of rooms include a display titled “Art and Ambition,” which highlights artworks from the 1820s to about 1850. Pioneering art by Thomas Doughty and Thomas Cole, who together shaped a new national appreciation for landscape painting, co-exist with bold furniture and cases displaying glass, silver, other metals, and ceramics—including monumental examples that represent a small fraction of the more than 560 pieces in the museum’s porcelain collection made locally at the Tucker Factory.

We decided to devote one section in this long gallery to Philadelphia artists, makers, and entrepreneurs of African descent. A mahogany double chest (or cheston- chest) inscribed “Thomas Gross/Maker” on the lower drawer is the only surviving piece of furniture that can be documented to the city’s thriving community of free Black artists in this period. On loan from descendants, portraits of Hiram Charles Montier and Elizabeth Brown Montier, also members of Philadelphia’s free Black community—the largest in the North—call attention to a new and more democratic access to portraiture, showing that by 1850 painted likenesses had come within reach of the growing middle class.

The final space—the Joan and Victor Johnson Gallery— returns to the arts of the Pennsylvania Germans. “Traditions on the Move” showcases the arts of the new communities in the counties to the north and west of Philadelphia through displays of paintings, painted chests, a still-vibrantly colored sampler from the collection of Leslie Miller, and the intricate compositions of fraktur from the Johnsons’ gift. The “wall of plates,” a much beloved display in our former gallery of Pennsylvania German art, returns on a smaller scale—accompanied by stronger interpretive material about their charming depictions—and often eyebrow-raising proverbs—as well as a brief video on the making of this earthenware. Displays of iron hardware highlight the perennial designs used by the Pennsylvania Germans. The installation also documents the role of enslaved and free African Americans in making iron goods. Perhaps they drew on their own ironmaking traditions from western and West Central Africa, demonstrating that Pennsylvania German social history reflects the larger story of the blending of cultures in the United States.

Altogether, the team spent four years mining our collection not only for our masterpieces, but also for the artists and patrons who had been silenced as histories were rewritten in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries. We worked hard to resurrect and celebrate the artistic contributions of all who were involved in making early American art vibrant—men and women, waves of immigrants who brought an international artistic language, and people of color whose contributions were almost always anonymous. Such themes resonated throughout the country in the wake of the murder of George Floyd and the strident calls for swifter progress toward more social justice.

The displays that curators design today compete for attention with an endless stream of digital images in the palms of so many visitors’ hands. To this end, strong sightlines, visually rich presentations, and clear narratives are designed to engage those with both the freshest and savviest of eyes—and everyone in between. Swapping works of art and rotating installations in the future will demonstrate the depth of our collections in focused displays (of, for example, light sensitive works such as historic upholstery, samplers, fraktur, or miniatures) and introduce new research, discoveries, and acquisitions.

For the PMA’s long-tenured curatorial staff, conservators, art handlers, and the generous supporters who know our collections the best, the new galleries have become a source of constant revelation, as we bring art into these rooms—and see it all anew.

Due to restrictions to thwart the spread of the Covid-19 virus, the exact date of the opening of the redesigned galleries has not yet been determined. Visit philamuseum.org for updates.

1Milton Bennett Medary was the primary architect of the Perelman Building, while Howell Lewis Shay, Horace Trumbauer, and Julian Abele were the primary architects of the main building, working with the firm of Zantinger, Borie and Medary. 2The most significant changes were the removal of sections of a large wall separating the West Entrance from the Great Stair Hall and of the Van Pelt auditorium, neither of which was part of the building’s original design and were added in 1959. While the Van Pelt auditorium was an amenable space, it inhibited visitors’ movement between the north and south wings; with its loss, the museum repurposed the large Pennsylvania Gallery in the Perelman Building into an auditorium. 3Such tables appeared with incredible frequency in Philadelphia in the first half of the 1700s, though none are known to survive. See, “Philadelphia Wills and Inventories” (microfilm, Joseph Downs Collection of Manuscripts and Printed Ephemera, Winterthur Museum, Library, and Garden), which lists slate-top tables belonging to John Craft, 1699; Hugh Lowdon, 1723; John McComb, 1723; Philip Monckton, 1723; William Dilworth, 1725; Mary Magdalene Peres, 1732; Paul Preston, 1732; Edward Horne, 1735; John Gibbs, 1735; Samuel Nicholas, 1753; and Wight Massey, 1762.

ALEXANDRA ALEVIZATOS KIRTLEY is the Montgomery- Garvan Curator of American Decorative Arts at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.