The Magazine ANTIQUES | November 2008

When and where the Seattle Art Museum was founded greatly shaped its collecting of American art—far from the art centers of the East Coast and comparatively late in this slowly developing city on the Pacific Northwest frontier. Long a student of Asian art, which his mother had also avidly collected, the museum’s founding director, Richard E. Fuller (see p. 104, Fig. 7), wanted the new museum to focus on Asian art. With its collecting underwritten entirely by his family’s fortunes (his parents both had significant family wealth, and his father was a prominent urological surgeon in New York), he understandably pursued his passion, spurred on by his uncommon sense of an Asian art collection’s particular relevance in a city on the Pacific Rim, a city having, as he saw it, stronger ties to Asia than to New York or Europe. While Californians were famously seeing their state as the North American Continent’s end, the fulfillment of a country’s westward march to settlement, Fuller was quite unconventionally seeing still young Seattle as something of a beginning, a portal to Asia. It is relevant to Fuller’s point of view that he was a geologist by training—having earned his doctorate at the University of Washington—and his understanding of an interconnectedness among the cultures of the Pacific Rim surely stems in part from his knowledge of the extensive, continuous system of oceanic trenches, geologic plates, and volcanic arcs that comprise the Pacific “Rim of Fire.”

Building a world-class collection of Asian art for Seattle required focus, and Fuller was not going to be distracted by nominal collecting in other areas. Nevertheless, having participated directly in the design and construction of the magnificent art deco style museum building atop Seattle’s Capitol Hill, in Volunteer Park, he was receptive to complementing the architecture with suitably decorative modern sculpture. In this he relied in significant measure upon the advice of his sister, Eugenia (Mrs. John C. Atwood Jr.) of Philadelphia, who directed him to any number of contemporary American works. For the entrance to the galleries she commissioned decorative gates by the Philadelphia architectural sculptor Samuel Yellin (1885–1940), and she also made gifts in that inaugural year of bronzes by Boris Lovet-Lorski (1894–1973) and William Hunt Diederich and was likely behind her brother’s purchase of other Diederich works, too, including a cut-tin, iron, and brass fire screen that was acquired in 1933 for the new museum’s board room (Fig. 4).

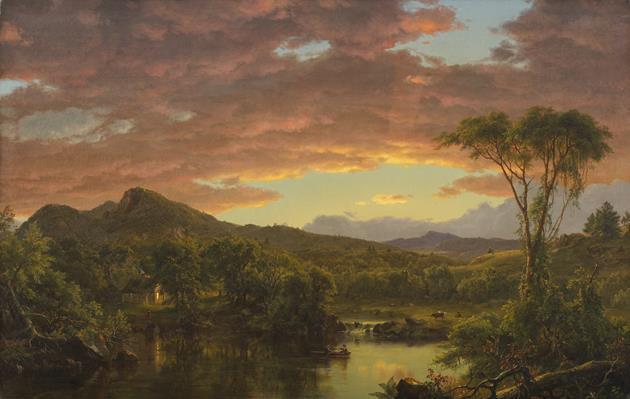

Fuller did believe that the best measure of the value of the institution would be the collection’s influence on artists, Seattle artists, and he regularly mounted exhibitions of the region’s contemporary art. He gathered around him artists who shared his sensibilities—Mark Tobey, Morris Graves, Guy Anderson, and Kenneth Callahan—who would twenty years after the museum’s founding be celebrated nationally as the Mystic Painters of the Northwest. From the outset, Fuller enthusiastically collected the work of his artist friends for the museum and encouraged museum patrons to do likewise, to the end that today the Seattle Art Museum is a leading repository of the work of these important modernists. On rare occasions during Fuller’s extraordinary forty-year tenure, from 1933 to 1973, works by historical American artists crept into the collection without fanfare, generally as gifts. These comprised a fairly lackluster group until 1965, when Frederic Edwin Church’s early masterwork, A Country Home (Fig. 3), came to the museum as a surprise gift of Mrs. Paul C. Carmichael of Seattle, a woman who was then, and remains still, unknown to anyone in the circle of art patrons in the city. This magnificent canvas had been in her family since it was acquired, probably directly from Church, sometime after it was the centerpiece of the annual spring exhibition at the National Academy of Design in New York in 1854.1 A Country Home was widely acclaimed by critics in Church’s day as the artist’s first great success, and it represented the consummation of his early efforts to establish himself as the rightful successor to Thomas Cole (1801–1848) as this country’s greatest painter of American scenery. Fuller expressed some uncertainty about adding the painting to the collection—Church was hardly the household name in 1965 that he is now. He nevertheless made the decision to retain it for the collection, and with it openly expressed a desire to consider building the museum’s holdings in nineteenth-century American landscape painting.

Fuller’s mild enthusiasm for nineteenth-century American landscape painting notwithstanding, another twenty years would pass before the museum actively began to pursue acquisitions in this area. It was only in 1987, through the fund-raising efforts of a small group of enthusiasts and museum supporters spurred on by the American art collectors Tom and Ann Barwick, that the Seattle Art Museum began in earnest to collect historical American art reflective of the arts outside the Pacific Northwest. Yet, that first important purchase in this area—a Japanese inspired window by John La Farge (Fig. 5)—fit perfectly, programmatically speaking, into the museum’s core collection of Asian arts, even if there was little else in Seattle to which it related. That would soon change.

Fig. 7. Amor Caritas by Augustus Saint-Gaudens (1848-1907), modeled 1898, this cast probably 1898. Signed and dated “AVGVSTVS/SAINT GAVDENS/MDCCCXCVlll” in the mold at lower left and inscribed “IN MEMORY OF/NANCY•LEGGE•WOOD•HOOPER/MDCCCXIX-MDCCXCVII” at bottom center. Bronze; height, 39 7/8, width 17, depth 4 1/2 inches. Purchased with acquisition funds and partial gift of Ann and Tom Barwick.

After 1987 new patrons rallied to make important acquisitions of American art possible for the museum. Significantly, the interest in American art built outside the museum first, and that in turn led to institutional collecting, when in many other places the dynamic has been quite the opposite, with museum holdings inspiring individual collectors. Seattle’s initial, all-important purchases of nineteenth-century American paintings were all public-sponsored, and, perhaps not surprisingly, they were all of regional interest and reflective of civic pride. In 1989 the museum acquired the romantic Smoky Sunrise, Astoria Harbor (Fig. 2) by the nineteenth-century Oregon artist Cleveland Rockwell, a figure still little known and rarely seen outside the Pacific Northwest. A year later the Barwicks helped make possible the purchase of Sanford Robinson Gifford’s magnificent late work Mount Rainier, Bay of Tacoma—Puget Sound (Fig. 8), a product of his summer travels to the region in 1874. In 2000 the museum made another major purchase of a great American painting depicting a local subject—Albert Bierstadt’s monumental 1870 canvas Puget Sound on the Pacific Coast (Fig. 1), certainly not a fully truthful depiction of the topography, but the artist’s earnest tribute to the ancient indigenous mariners who plied these waters and inhabited these lands.

Fig. 9. Dr. Silvester Gardiner (1708-1786) by John Singleton Copley (1738-1815), probably 1772. Oil on canvas, 50 by 40 inches. Gift of Ann and Tom Barwick, Barney A. Ebsworth, Maggie and Douglas Walker, Virginia and Bagley Wright, and Ann P. Wyckoff; and gift of others by exchange; with additional funds from the American Art Support Fund and the American Art Acquisition Fund in honor of the museum’s 75th Anniversary.

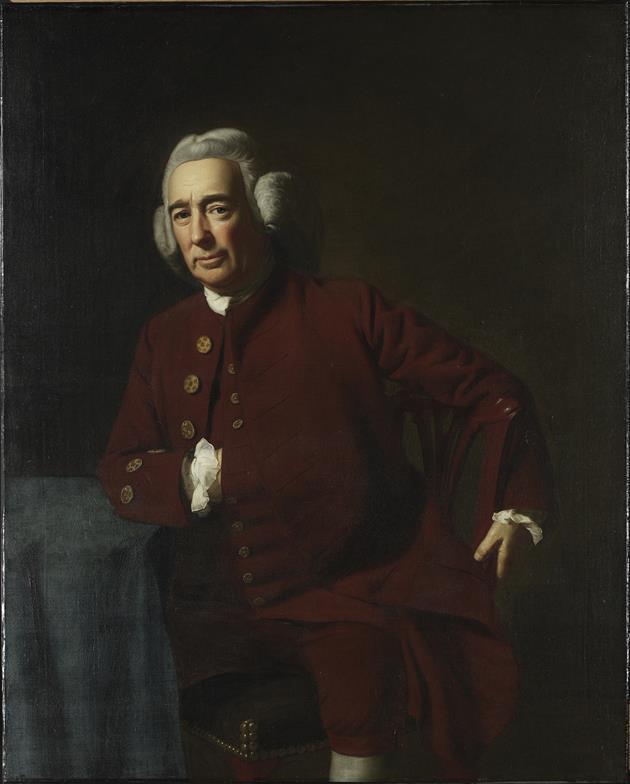

With these acquisitions the need for an American art collection that could represent more than just the region’s surpassing physical beauty became apparent, and major works of American art entered the museum with ever greater frequency. The Barwicks donated the luminous Narragansett Bay of 1861 by John Frederick Kensett (1816–1872) in 2001, and that same year, to honor the scholarship of then deputy director Trevor Fairbrother, the museum acquired John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Léon Delafosse(Fig. 6), the artist’s tribute to a young pianist friend. Purchases made since 2004 have included an early cast of Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s elegiac bronze, Amor Caritas (Fig. 7), this example created as a memorial to the Bostonian Nancy Legge Wood Hooper, who died in 1898. Paul Manship—a leading figure of the art deco period who was not represented in the modern American sculpture collection that Fuller and his sister built in the 1930s—entered the collection just this year with the 1921 bronze Spear Thrower (Fig. 12). In 2006 the museum saw its most ambitious purchase to date of a historical American work: John Singleton Copley’s engaging likeness of Dr. Silvester Gardiner,probably painted in 1772 (Fig. 9). Arguably the most significant work by the colonial painter still in private hands, the Gardiner portrait was acquired directly from the subject’s family. With his winsome expression, Gardiner is an appealing figure. One of the most learned men in Boston, he was a physician who made a fortune as a merchant and land developer. Copley knew him well and let the amusement in his friend’s eyes speak for the man’s character. Though not pictured, the portrait retains its original rococo style frame carved by John Welch (1711–1789).

A group of museum patrons—all significant American art collectors, who now comprise a very influential force in Seattle—made possible the establishment of an American art department at the museum in 2004, thus ensuring that the collection and the exhibitions and scholarly programs would continue to grow. Their support signaled that the city’s unsurpassed private collections would now play an important role in the presentation of American art. The culmination of the museum’s recent building program has been the overwhelming outpouring from collectors and donors who have given or pledged works to the permanent collection in honor of the museum’s seventy-fifth anniversary.

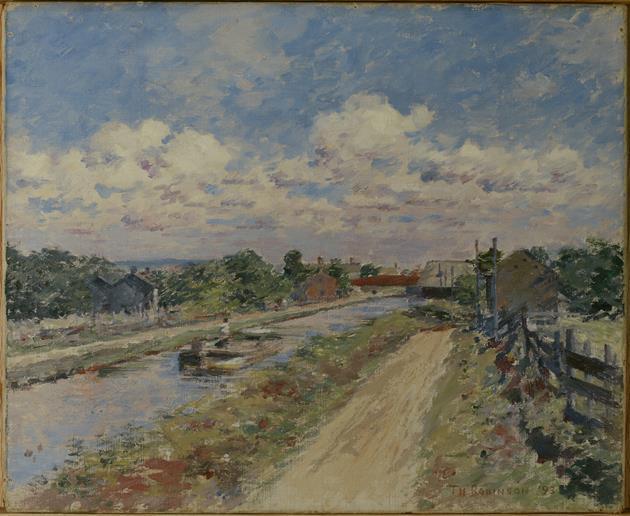

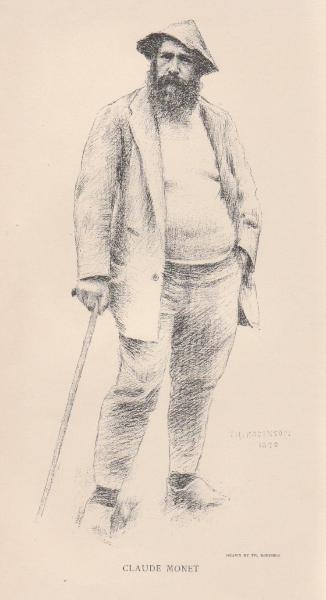

Among the highlights of the pledged and promised gifts are two works by Theodore Robinson, whose irrepressible inclinations toward experimentation led him to seek the experience of French impressionism firsthand through Claude Monet. Robinson befriended Monet during an extended stay in Giverny in the late 1880s, and his informal drawing of the older artist is a record of their friendship (Fig. 11). When Robinson returned home to New York in 1892, after another extended period in France, he faced his native land with a fervent desire to rediscover and celebrate it. The subject of On the Canal (Fig. 10) of 1893 might seem to be the French countryside, but in fact it is a view on the Delaware and Hudson Canal at Port Ben, near Napanoch, New York.

For John Twachtman the intense focus that attended the study of landscape and light in its ever-changing complexity led to bold and intuitive experiments in color and form, especially when he brought his meditative scrutiny to bear on a favorite corner of the natural world: the hemlock grove and pool that graced his Connecticut farm property. Twachtman painted aspects of the quiet wooded glade time and again, but never in such a cursory and wholly suggestive manner as in the small intimate canvas that has come to the museum (Fig. 15). This is possibly the work entitled Hemlock Pool (Autumn) that Twachtman submitted to the 1894 winter exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia. Though it was awarded the gold medal as the best painting in the show by a small jury of artists, the painting was largely considered an outrage—“A thing of shreds and patches,” one critic declared; “Hardly a picture,” was how another dismissed it.2

Willard Leroy Metcalf’s Cornish Hills (Fig. 13) arguably stands as the centerpiece of his career, a large painting made in an exceptional season of work, in 1911, at the artists’ enclave of Cornish, New Hampshire. In the snow-covered hills there he discovered the beauty of the winter landscape, a landscape reduced to a few solid forms, so different from the soft tapestries of spring and autumn. The stillness of winter engaged Metcalf’s spiritual side, bringing a deeply meditative presence to his work.The Seattle Art Museum’s collection of early twentieth-century art once focused largely on the Pacific Northwest, but recent and promised gifts of early modern American art have added a New York dimension. Major works have come from Barney A. Ebsworth, whose collecting has helped to define this field. Ebsworth demonstrated his keen instinct about what constitutes a masterwork with his early acquisition of Edward Hopper’s Chop Suey of 1929 (see p. 107, Fig. 11). One of Hopper’s most familiar and beloved pictures, Chop Suey is rightly seen as a defining work in the artist’s career, the work by which he established himself as an incisive painter of the modern urban scene. With it he established his enduring iconography of the modern American woman, a figure long associated with home and hearth but now, as a part of the work-a-day world, a figure increasingly shaped by the urban places she inhabits—restaurants, movie theaters, and train cars. The New York shop girls who lunched at chop suey restaurants were adventuresome and unconventional, for they had broken free of old Victorian taboos and were now engaged in the thoroughly modern activity of dining in public unescorted by men.

Chop Suey, the centerpiece of the museum’s Edward Hopper’s Women exhibition, which opens November 13, is a promised bequest and will one day join other recent gifs to the museum from the Ebsworth Collection. Painting Number 49, Berlin (frontispiece) is from a group of paintings that Marsden Hartley made as tributes to a fallen friend, a young German cavalryman named Lieutenant Karl von Freyburg (d. 1914). This emblematic portrait is emphatically cruciform. The carefully organized arrangement also conforms to the oldest battlefield tribute: the trophy, the ancient Greek tropaion, an arrangement of a fallen soldier’s arms and standards set up by the victors on the battlefield at the spot where the enemy was routed.

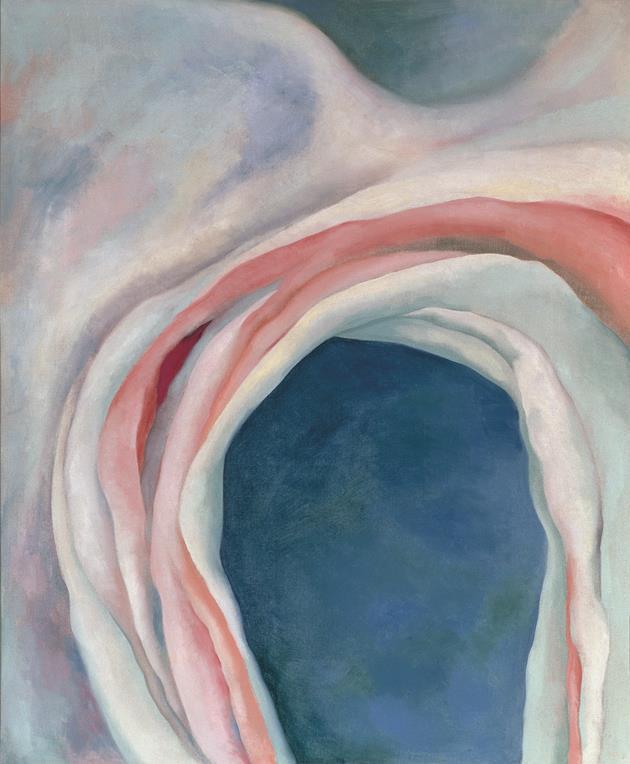

Also from the Ebsworth Collection is Georgia O’Keeffe’s Music—Pink and Blue No. 1 of 1918 (Fig. 14), the work that in large measure defined what we have come to think about O’Keeffe’s art. It is representative of works that to some—Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946) and Hartley especially—seemed to support a sexual interpretation of the young woman artist’s obscure abstractions. Hartley famously described O’Keeffe’s paintings in 1921 as representing “the world of a woman turned inside out.”3 For her, this early abstraction was a visualization of aural sensations—hence the title, Music. Stieglitz saw the canvas differently, however. He made an emblematic portrait of O’Keeffe that played on this painting in which the canvas is coupled unsubtly with the phallic form of a sculpture she had created in 1916. After it was unveiled in Stieglitz’s major exhibition of O’Keeffe’s work in 1923, she seems to have secreted the painting away and not shown it again until after his death.4 In 1974 O’Keeffe sold Music—Pink and Blue No. 1 to Ebsworth, who had become her friend.The late Gwendolyn Knight and her husband Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000) settled in Seattle in 1971, but their respective painting careers were forged in Harlem. Though Seattle has long focused on and celebrated the years when the two lived and worked there, the museum now has a work that makes reference to their formative years—Augusta Savage’s plaster bust of the young Knight (Fig. 16). Although her training had been solidly in the classical tradition, Savage invested her work with a particular feeling for individualization. Knight was a stunning beauty, tall and graceful. But it was her reserve, thoughtfulness, and introspection—qualities made manifest in this bust—that truly impressed her friends.

The developing American art collection at the Seattle Art Museum is truly a reflection of place. For much of its long history, the museum accepted that historical American art might be better understood in the context of the cities where that art was created, the cities that were the country’s major early art centers—New York, Boston, and Philadelphia. Seattle’s art history was different and separate from the historical narrative that was centered on the country’s eastern seaboard, at least as far as Richard Fuller was concerned. But the new enthusiasm for American art that has been building in Seattle over the past twenty years underscores how much the city itself has changed very recently. The unprecedented influx of new residents from all over the country has altered the way the museum’s visitors think about their cultural touchstones. Bostonian Copley and New Yorker Hopper are as resonant in Seattle now as are the works of Tobey and Graves. Where one man’s vision—Fuller’s—once shaped the museum’s presentation of artistic achievement, now a large population of collectors and supporters has spurred the growth of diverse collections, American art included. Today the strength of that collection is not measured wholly by the extraordinary works of art that have entered the building thus far—the number of accessioned works of American art is still quite small. The strength of Seattle’s American art program is more accurately seen in the opportunities that this museum has to bring to the public major works from collections that are still building in this city among those who see American art, not as an expression of any one part of the country or any one people but as a worthy representation of our broad cultural diversity.

1 According to the donor, in whose family the painting descended, it was probably acquired by her great-grandfather General Joseph Gardner Swift (1783–1865); by 1862, when it was shown at the Third Annual Exhibition of the Artist’s Fund Society of New York, it was owned by Swift’s son-in-law Peter Richards Jr. 2 December 1894 reviews quoted in Lisa N. Peters, John Twachtman (1853–1902): A Painter’s Painter (Spanierman Gallery, New York, 2006), p. 67. 3 Marsden Hartley, Adventures in the Arts: Informal Chapters on Painters, Vaudeville, and Poets (Boni and Liveright, New York, 1921), p. 116. 4 See Barbara Buhler Lynes with Russell Bowman, O’Keeffe’s O’Keeffes: The Artist’s Collection (Milwaukee Art Museum, Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, and Thames and Hudson, New York, 2001), pp. 58, 60.

PATRICIA JUNKER is the Ann M. Barwick Curator of American Art at the Seattle Art Museum.