The entrance was down an alleyway and the front door was tucked in under an arch. I pulled the manual mechanical doorbell to gain entrance, and my wife, Josyane, and I found ourselves invited directly into a small private sitting room. The following couple of hours simply changed our lives.

It must have been around 1977. We had only been in business for a short time and a new client suggested we should visit Kettle’s Yard, in Cambridge. At that time, neither of us knew of its existence. Sadly, the founder and creator, H. S. (Jim) Ede, was no longer in residence. After living there for fifteen years, in 1973 he took his wife back to Edinburgh, where she was from, and they spent the last years of their lives there, leaving Kettle’s Yard in the care of Cambridge University.

Ede was born in Wales in 1895, the son of a solicitor. He went to the Leys School in Cambridge, going on to study painting at the Newlyn School of Art in 1912, before joining up to serve in the First World War. After the war he resumed his studies at the Slade School of Fine Art, before working as a photographer’s assistant at the National Gallery and then as an assistant curator at the Tate Gallery. He left the Tate in 1936, reputedly frustrated by the reluctance of the establishment to embrace the work of contemporary artists, and for the next twenty years lived a somewhat itinerant life, writing and lecturing on art in Europe and America, whilst keeping a home base, first in Morocco and then in France. He returned to Britain in 1956, in his early sixties, with a vision to create “a living place where works of art would be enjoyed, inherent to the domestic setting, where young people could be at home unhampered by the greater austerity of the museum or public art gallery, and where an informality might infuse an underlying formality.”* Ede created Kettle’s Yard from four dilapidated cottages, immediately adjacent to St. Peter’s Church, off Honey Hill in Cambridge.

Having been invited in, we found ourselves facing a small brick fireplace, the mantel fashioned from old terra-cotta tiles, on which there was a group of objects—still, composed, balanced, and quiet. Even in those years we recognized that these pieces were not superlative, they were not of any great rarity, nor even individually remarkable, and certainly not typical of what we understood to be of “museum quality.” In fact, at the center of the composition stood the achingly fragile remnants of two seashells, standing upright, as if dancing with each other, whilst their shadows echoed their form on the reflective surface of the oval ceramic dish behind them. We were entranced.

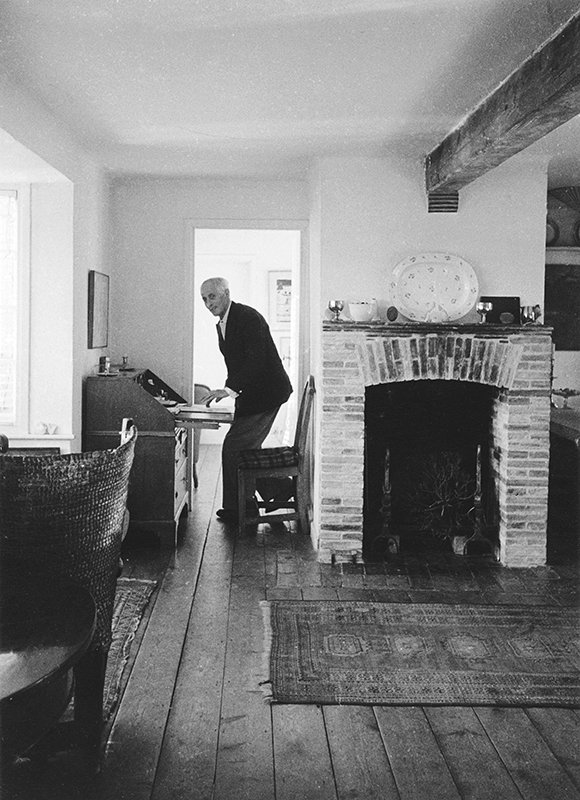

There was an immediate sense of peace, while the woman who had ushered us in explained that this was a home, and we were encouraged to treat it as such, to feel free to sit in the chairs, look through the books, and take our time. We wandered in silence for a while. With plain white-painted walls and raw wooden floors, the rooms were furnished largely with unexceptional, honest antique provincial and vernacular furniture, curated compositions of glass, china, wood, and stone, found objects, and modernist sculpture, paintings and drawings by significant mid twentieth–century artists, all somehow related to each other, each piece significant to the composition of the space it occupied, bathed in natural daylight and punctuated by the odd vase of freshly cut flowers. No labels, no protective ropes, and no spotlights.

We were immediately drawn to the simple beauty of a collection of sea-rounded and smoothly polished pebbles, graded by tone and color and arranged in a spiral atop a circular scrubbed-top table in the light of a bay window, a grouping and placement that may now be considered “an installation,” but was here simply a celebration of form, color, and texture, presented in a sensitive orderly composition (Fig. 5). We were now moving faster into each connected space, excited and inquisitive about what we might find. We went into a bathroom and discovered an Alfred Wallis painting by the cistern; there were crusty rocks selected for their naturally tactile quality and their relationship to each other, sitting on a chest of drawers beside polished ivory hairbrushes, curiously juxtaposed yet balanced and compelling. Then, an excitingly diminutive Ben Nicholson abstract (Fig. 4) screwed to the wall beneath an architectural molding, as if incidental to the space but drawing the eye. Everywhere there were groups, patterns, compositions, and light, wonderful light. Many of the windows and windowsills were dressed with plants, silhouetted against the light that poured into the spaces through their graphic green leaves or reflected and refracted off hard, polished surfaces, yet somehow even in the smallest rooms there was no sense of clutter. Ede wrote in A Way of Life: Kettle’s Yard: “Glass and china play their part in Kettle’s Yard; there is hardly a room without, even cracked things, tea cups into which light falls like sunshine into pools. All this makes a home to live in, a place where people feel at rest.”

Fig. 7. Above the dining/sitting room is what was Helen Ede’s private sitting room, referred to as the Bechstein Room for her Bechstein piano. Allitt photograph.

Fig. 8. Suspended in the foreground is Disc by Gregorio Vardanega (1923–2007), c. 1960; behind is an untitled painting by Nicholson from 1944 and The Heron, a stoneware vase by William Staite Murray (1881–1962), c. 1928. Allitt photograph.

A natural sense of sanctuary pervades the small rooms, with a refreshing energy created by the placement of the artworks and objects that is enhanced by their relationships to each other. Although carefully considered, it all seems entirely natural. Ede was a believer, a spiritual Christian man, and it has been suggested that faith grew in him during his time on the front in the Great War and possibly inspired in him this desire to acknowledge and celebrate what he described as “the sacrament of the present moment”—I guess what people today describe as “mindfulness.” Josyane had trained at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London and I was privileged to study under the legendary Derek Shrub at Sotheby’s. We were both introduced to the mainstream art historical narrative in different ways, but both taught to identify and categorize works by their style and quality. In this time-honored fashion we slowly built up our personal visual reference libraries and grew to feel comfortable enough relying on this resource to start our own business. We were not taught about “eye,” taste, human response, or feeling for art, yet these were the reasons we sought to fashion a career in the field. After just a few minutes in Kettle’s Yard we felt we were somewhere special, somewhere undemanding yet celebratory and pleasurable—almost a reminder that art can be important and certainly that the selection and placement of pieces is an art form in its own right. It made “things” feel worthwhile.

Ede collected all his life; he championed the work of Wallis, Ben and Winifred Nicholson, Christopher “Kit” Wood, Barbara Hepworth, and Bryan Pearce during the early years of their careers—as well as Henri Gaudier-Brzeska after his untimely death—and befriended many of them. He was also a dedicated art “forager” drawn to explore antiques and junk shops with his eye always alert for natural “found objects,” and Kettle’s Yard was created around these things when he settled back in Cambridge.

Ede was a man of modest means, yet somehow had a way of gathering together art that spoke to him, by exchange and barter. Through his writing it is evident that he did not research many of the works he owned, particularly the decorative arts and furnishings. He tells where they were found and often of how little they cost, but virtually nothing of their history or origins beyond that and the part they play in the interior spaces of Kettle’s Yard. It was the satisfaction of the composition that drove him, the balance, the physical relationships, and the play of light. The collection is presented as a whole, as an installation, and as such Kettle’s Yard is witness to curation as a way of making art.

Ede loved people and sharing the pleasure he derived from Kettle’s Yard and what he described as “an elegance of living.” He held open houses on weekday afternoons to university students, who gained access as we did by ringing the mechanical bell, and was thus able to realize his dream of sharing the art and place with like-minded people in a domestic setting. “Looking back over this constant ringing of the bell,” he wrote, “it was always with a sense of interest and adventure that I heard its sound;” even whilst maintaining the house in preparation for visitors, “the so-called chores I turn to joy; the sweeping of a floor, dust slanting in rays of light, the quality of wood or stone, the cleaning of a window, that thrilling, insubstantial substance, glass, hard against driven rain, yet liquid to light.”

At the top of a staircase stands a handsome eighteenth- or nineteenth-century Norwegian dug-out chair, or “Kubbestol,” only the second such chair I’d seen at that time. It is sculptural, richly patinated, and, carved with an arcaded panel beneath the seat and further abstract geometric motifs, it has a noble sense of history. Honestly, it is the only significant piece of antique furniture in the collection, yet somehow feels contemporary in the context of Kettle’s Yard, where it is celebrated for its form and texture. The chair stands on the threshold of the entrance to the large extension out of the fourth original cottage that Leslie Martin designed for Ede.

The motivation for this large, airily modern, two-floor extension was Ede’s desire to display his burgeoning collection, hold exhibitions, and host musical events, and the opening in 1970 was celebrated with a performance by Jacqueline du Pré and Daniel Barenboim. Kettle’s Yard continues to host regular exhibitions and live musical events throughout the year. Clean lined and spacious, particularly in comparison to the cottages, the fabric of the extension nonetheless incorporates similar materials, with bare wooden, brick, and tiled floors, glass, and plain white-painted walls. The same sense of calm serenity exists here. However you also now get a better idea of the scale and quality of the collection that Ede amassed. It is well known that Ede really “discovered” the work of Gaudier-Brzeska; he wrote a book about him and bought most of his estate after it was rejected by the Tate Gallery in London. Amongst many others there are two powerful and significant works by the sculptor: Dancer (Fig. 9), a tangible celebration of movement in bronze, and Bird Swallowing a Fish (Fig. 13), fashioned from plaster and painted a dark verdigris color, which sits on a massive sea-worn driftwood tree trunk that Ede found washed up on a beach in the Isles of Scilly. Together, they comprise one of the most rewarding compositions in the collection. There is also the richly textured Sculptural Object by Henry Moore, as well as the sensual white marble Spirality by Kenji Umeda. There is a waist-high solid balustrade on which a huge collection of works by Alfred Wallis is closely hung; a bold black and white collage triptych by Italo Valenti set almost like an altarpiece above a simple console (Fig. 17); Ben Nicholsons everywhere; and scattered works by Hepworth, Brancusi, Bernard Leach, Miró, and many others.

On the upper floor of the extension and set back at one end of the space is a large table, surrounded on three sides by open bookshelves up to chest height, along the top of which are small sculptures, framed works on paper, ceramics, glass, and found objects. The wide-ranging books cover art subjects related to works and artists represented in the collection and to other broadly similar topics. There is no librarian or security guard, but a scattered variety of chairs is an unspoken invitation to settle and linger. To flick through or read, to rest or study, whatever, the space is inviting and convivial, as other visitors peacefully leaf through books or simply reflect on life. We didn’t want to leave. That first visit to Kettle’s Yard was an epiphanic moment for us. We discovered a place where objects were honored for being what they were. Where a seedpod, a glass fishing float, and a curated selection of pebbles were worthy of attention; where harmony, daylight, placement, and the unspoken emotions of art are celebrated. Where plants and books play an important role; where balance and composition are the champions; where texture and tone are juxtaposed and harmonized—simply where the confidence of one man’s eye was concentrated. We left believing in that sense of value, that just being touched by inanimate “things,” was somehow worthwhile and can influence the way we live and the values we cherish.

Ede wrote almost prophetically in his book, “it is salutary that in a world rocked by greed, misunderstanding and fear, with the imminence of collapse into unbelievable horrors, it is still possible and justifiable to find important the exact placing of two pebbles.”

Fig. 16. A variety of objects from Ede’s collection is seen here, such as a thirteenth- or fourteenth-century Buddha sculpture from the Phra Prang Sam Yot temple, Lopburi, Thailand, at left; sculptures and a drawing by Gaudier-Brzeska; a drawing by Mario Sironi (1885–1961); and paintings by Ben Nicholson. Allitt photograph.

Fig. 17. More pieces from Ede’s collection, including three Italo Valenti (1912–1995) collages from 1964, and a bowl by Lucie Rie, 1971.

We came away inspired, and with a belief that we, like everyone, could trust our instinct and back our eye, knowing that if nothing else we would now only live and work with pieces that touched us, or which we recognized for qualities that we valued, irrespective of the dictates of fashion, period, maker, medium, or value. After visiting Kettle’s Yard, we were never the same.