For more than five decades, Jerry Gretzinger, a seventy-seven-year-old resident of Maple City, Michigan, has been drawing a map. It won’t help you find your way to any place on earth, nor to anywhere else in the universe. It’s called Jerry’s Map, and it charts the contours of an imaginary world.

Gretzinger traces his fascination with cartography to a childhood spent thumbing through National Geographic, back when it was illustrated with maps and diagrams by A. Hoen & Company and Marie Tharp, among others. He took his first stab at making maps of his own when he was in high school.

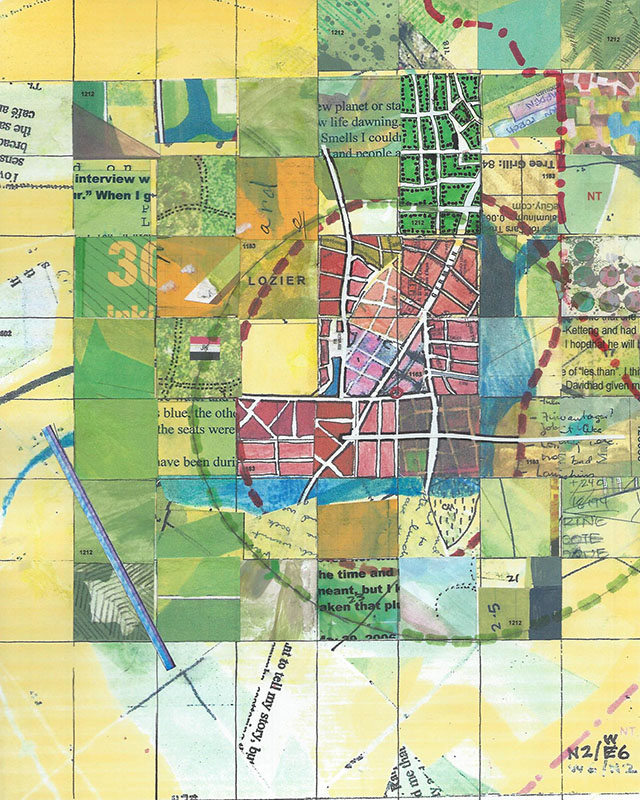

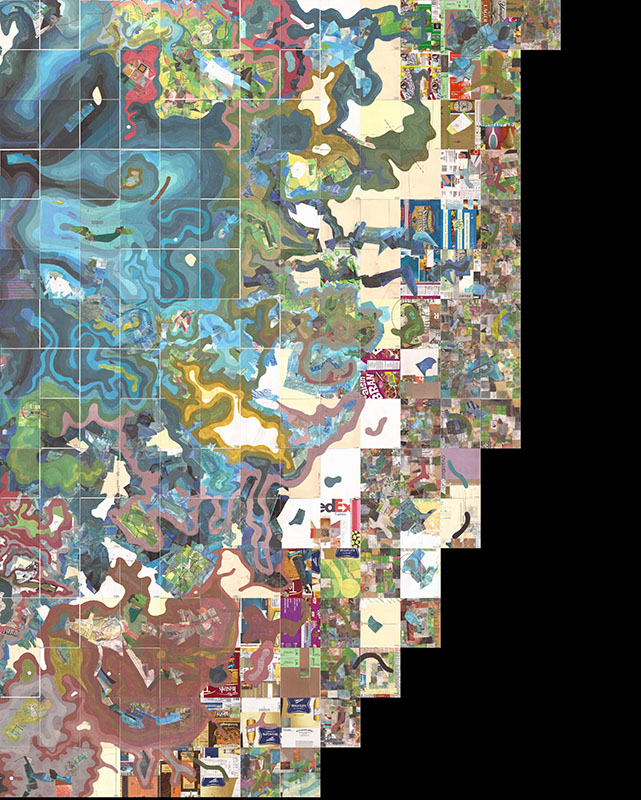

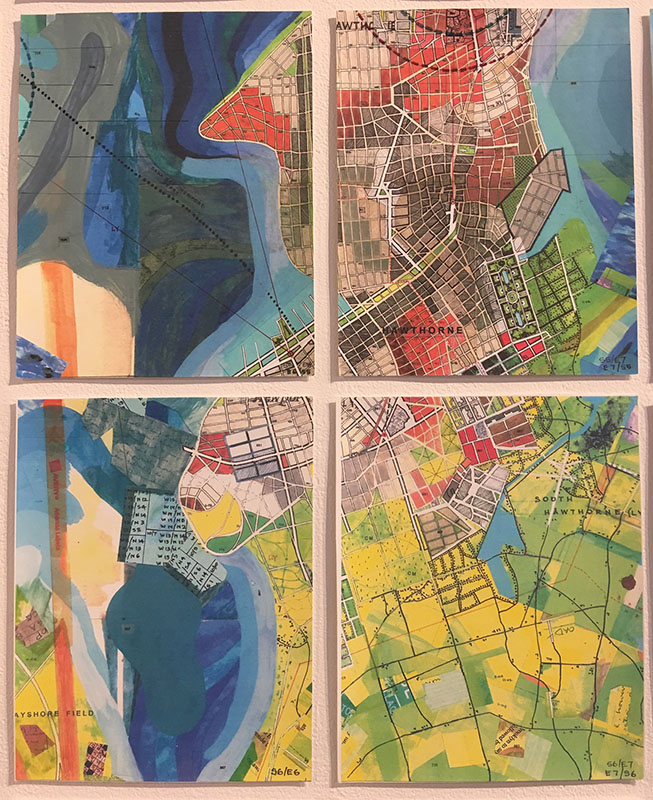

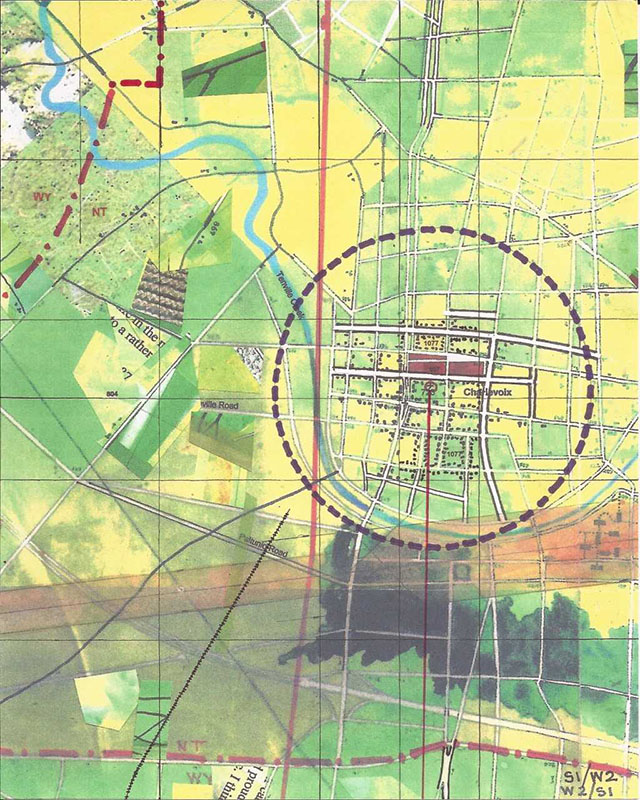

Gretzinger got more serious in 1963, when he began what would become Jerry’s Map on panels of paper that he covered with scribbled city blocks and countrysides, rivers, lakes, and roads in pencil, india ink, and watercolor or gouache. The map grew and grew.

Eventually, life intervened. He raised a family and managed a handbag company, then a women’s fashion company, Staley/Gretzinger, with his wife, Meg Staley, and in 1983 he put Jerry’s Map in the attic.

That might have been the end of the story. But in 2003, coinciding with the closing of Staley/Gretzinger and the latter partner’s retirement, the couple’s son discovered the map and convinced his father to continue working on it.

He did and “I just kept going,” Gretzinger says. “I was intrigued to find where it would go.” He let his drawing hand direct him, as well as a set of mapmaking rules (like “[create a] new parish” and “[invent] town names”) he’d jotted down on a set of note cards. The technology of the twenty-first century enabled Gretzinger to scan and reproduce map panels after he’d sketched them, enlarging cities and adding roads, lakes, fields, and other features, exponentially increasing the efficiency of Gretzinger’s work, as well as the map’s detail and its potential for growth.

Acquaintances were intrigued. So many people asked him about the “world history” of the place he was depicting that Gretzinger was forced to invent one. He came up with the idea of a human zoo created by beings in a higher dimension and populated by re-animated humans. “Since it looked kind of like the Midwest”—which Gretzinger has called home for most of his life—”it didn’t make sense to [invent] little beady-eyed creatures to inhabit it,” he explains.

Since year zero in map time—1963, to be exact—Gretzinger has been keeping detailed charts of fictional population growth in the cities. Whenever the population of the entire map grows by 1 percent, Gretzinger rings in a new year. Recently, he’s started picking names for cities based on notable who died in that year in the real world. For instance, in map year 1307, a city got the name “Longshanks,” since Edward I died in that year. The most recent new city is named Montepulciano, after the Italian saint Agnes of Montepulciano, a fourteenth-century Dominican prioress credited with miracles. The map is currently in year 1323.

An artist friend encouraged Gretzinger to exhibit, which he’s done some twenty-five times since 2003. In 2015, when he had overlapping shows, Gretzinger made two versions of Jerry’s Map, called Exhibition Set 1 and Exhibition Set 2, which differ in minute ways: new city blocks have been added to some cities, new roads. Exhibition Set 2 is currently on view at Intuit: The Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art in Chicago.

Gretzinger has a robust web presence, posting videos, pictures, and essays that explain his process and theories to the throngs of fans Jerry’s Map has acquired over the years. He attributes the map’s success to people being impressed with its size—by now it’s made up of some 3,600 eight-by-ten-inch panels, and if it were exhibited in its entirety would cover the same amount of ground as a basketball court—its vibrant colors, as well as the the je ne sais quoi appeal maps hold for many people, the same appeal that inflamed him when he was a child. All that considered, “I never thought it would become this big,” says Gretzinger. It’s a statement that can be taken a couple of ways.