“You ought to be ashamed, I said, to look so antique” T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land, 1922

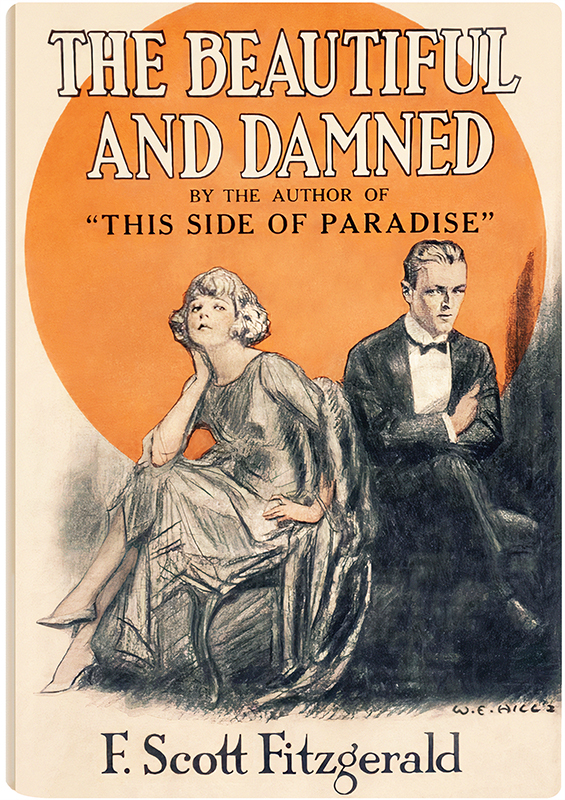

During the summer of 2021, I spent my days considering the year 1922, when Homer Eaton Keyes (Fig. 3), formerly a professor at Dartmouth College, turned his back on “the mad pace of America” (F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Beautiful and Damned, 1922 [Fig. 4]), to launch ANTIQUES magazine in Boston, a city whose traditional culture had already been eclipsed by a world “busy with reforms and ‘movements,’ with fads and fetishes and frivolities” (Edith Wharton, The Age of Innocence, Pulitzer Prize, 1921).

Elizabeth Stillinger gives a scrupulous account of Mr. Keyes elsewhere in these pages, which leaves me free to consider his seemingly quixotic venture amidst a vanguard culture eager “to be a mirror to modernity” (William Carlos Williams, “The Wanderer,” 1917), and a social landscape vexed by issues of immigration and xenophobia, prohibition and rampant alcoholism, progressivism and its discontents, the rise of mass media, and the supposed demise of civility. The year 1922 wasn’t all flappers and bathtub gin, not by a long shot. But it certainly wasn’t highboys and Hadley chests either.

If the following thoughts seem in themselves quixotic, they may explain my arrival at ANTIQUES in the inauspicious year of 2008, after spending my formative years in journalism at The Nation magazine. I like a niche that allows me to look where others do not.

To return to the fractious year of 1922, it’s not surprising that the other notable magazine launched then was Reader’s Digest, in which the bright-siding of America (bringing “out the good in people and families everywhere”) continues to this day (Fig. 5).

To his credit, Homer Eaton Keyes had something different and deeper in mind as he ventured forth in high spirits and jaunty prose to introduce the inaugural issue of ANTIQUES. He knew what he was up against: an art world attuned to the new, to artists such as Kandinsky and Klee, a postwar boom in literature where T. S. Eliot, Marianne Moore, e. e. cummings, and Wallace Stevens were fracturing traditional expectations. And yet he clearly wanted his magazine to be more than a haven in a harried world, nor was he the mossback some folks might suppose . . . at least not in those early years.

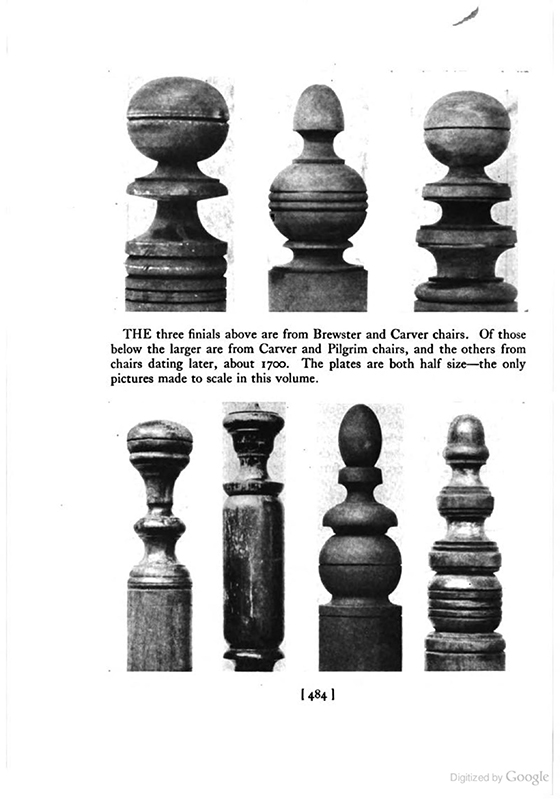

If Flaubert thought the worst thing about the present was the future, Keyes thought its best hope was in the past. Of course he was not alone in this. The colonial revival was quietly ticking along: Wallace Nutting’s Furniture of the Pilgrim Century had appeared in 1921 (Fig. 9), and the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Furniture Masterpieces of Duncan Phyfe exhibition opened in 1922.

More cosmopolitan in scope and deeper than these and other backward glances of the time, ANTIQUES in its first year cast a wide net over earlier decorative arts—from Western Europe to Russia with love . . . and back home again. Far from looking back at an America that never was, those first twelve issues are a grab bag of virtually everything in the field, and they seem to me not so much antique as very much of their time, as we will see.

A Journey through the Waste Land

Perhaps the most durable cultural event of 1922 was The Waste Land, that long, obscure, and antic poem by the St. Louis native Thomas Stearns Eliot (Fig. 6). Reviewed widely, its reputation secured by year’s end, the poem has been crudely described as a fever dream, a highbrow record of a lowbrow nervous breakdown, a mess, and a mishigas. Even Eliot, unsure of what he had wrought, thought his poem could communicate without being understood. He was right. It has endured.

A museum of culture, The Waste Land has meant much to me. All those glancing references and quotes from Chaucer to Baudelaire, musical notes from Wagner to jazz, things I love and those I still don’t know (the Upanishads), or don’t cotton to (Tarot cards), they sing to me. I feel the anguish of “the unreal city” and a thrill akin to a great jazz solo when quote upon quote leads inexorably to a sublime invention. Eliot, too, preferred the past to the present: “These fragments I have stored against my ruins,” the spectral voice says toward the end of the poem. Homer Eaton Keyes may not have read the poem but he would have understood the emotion . . . and the impulse.

Babbitt Agonistes

At the other end of the cultural spectrum in 1922 is Sinclair Lewis’s Babbitt, a favorite novel of mine—and one unfairly written off as the story of a boob, a booster, and an empty vessel (Fig. 7). George Babbitt, citizen of the fictional midwestern city of Zenith is broader and deeper than that and so was Sinclair Lewis, perhaps our finest anthropologist of American angst. As Babbitt dreams a dream “more romantic than scarlet pagodas by a silver sea” and runs amok with booze and broads in pursuit of that dream, Zenith, “a city with gigantic power—gigantic buildings, gigantic machines”—crushes him under its heel, seducing him with the mass-produced goods that seemed at first proofs of excellence, and then became “the substitutes for joy and passion and wisdom.”

At one point George Babbitt goes to Maine in pursuit of an older America. It doesn’t help. There is an air of grim finality about the America of Zenith, especially for readers of ANTIQUES, who will be amused to find the novelist casting a satirical eye on the homes in George Babbitt’s neighborhood, where, amidst new appliances and mass-produced furnishings, the pictures on the walls include a sad “‘hand-colored’ photograph of a Colonial room,” undoubtedly a Wallace Nutting. I like to think Homer Eaton Keyes must have enjoyed this book.

Disenchanting the Industrial Sublime: The precisionist’s yield to a revelation

I have a particular fondness for artists like Charles Sheeler, Charles Demuth, Joseph Stella, and especially George Ault. The air of excitement and ambivalence about what modernity had wrought is palpable in their factories, bridges, and smokestacks. By 1922 Ault was in Provincetown, Massachusetts, giving a bracing edge to the rural familiar, and I was eager to write about him until I discovered that the most popular print of 1922—and the most popular print for a century to come—was Daybreak, a gauzy dreamscape by Maxfield Parrish (Fig. 11).

I did not know that. I didn’t even know the print, being mostly familiar with Parrish from his mural in the King Cole Bar of the St. Regis Hotel in New York. But once I had considered Daybreak and read some of Sylvia Yount’s analysis of the print in her catalogue raisonné of Parrish, it made perfect sense, at least in 1922. Women had the vote, women were trouble, women were a destabilizing force. Parrish’s print in Yount’s words, “both titillating and calming viewers with an ideal of naked innocence and youthful abandon,” offered a course correction to the runaway dames of F. Scott Fitzgerald and others.

For all its antique air, Daybreak was in one respect thoroughly modern: it was and remains a marketing phenomenon, a triumph of consumer culture and mass production that must have alarmed a former professor of art history like Homer Eaton Keyes, who preferred things made by hand and one at a time.

Drop Me off in Harlem

I have left a favorite cultural phenomenon of our watershed year until last: In full swing by 1922 when Duke Ellington arrived in New York, the Harlem Renaissance continued to light up the literary and musical landscape for years to come. But those four square miles north of 110th Street were another country, and one whose borders did not touch on things “antique.” Even by the decade’s end when ANTIQUES moved to New York, I do not think we would have found Homer Eaton Keyes stompin’ at the Savoy.

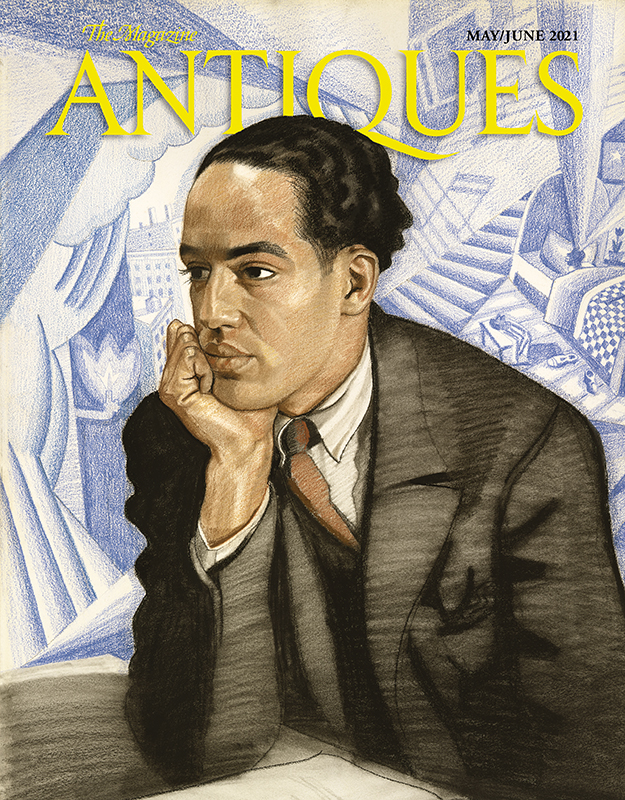

That was then. Borders open, the past endures, and in the spring of 2021 a portrait of Langston Hughes graced the cover of ANTIQUES (Fig. 12), placed there by just the sixth editor in the magazine’s one-hundred-year history.

ELIZABETH POCHODA was the editor of ANTIQUES from 2008 to 2016.