Known for her inventive construction techniques, fiber artist Kay Sekimachi has charted a creative career that ranks alongside those of the great mid-century artists working in fiber, from Anni Albers to Lenore Tawney and Ed Rossbach. Long respected for her intimate knowledge of the loom and its expansive possibilities, Sekimachi’s formal experiments in fiber have tested the limits of her tools and materials and led to works of uncommon precision and elegance. Her seventy years making art were recently celebrated in a serene, sensuous, and cerebral exhibition, Kay Sekimachi: Geometries, at the University of California’s Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive—only the latest honor for the Northern California artist.

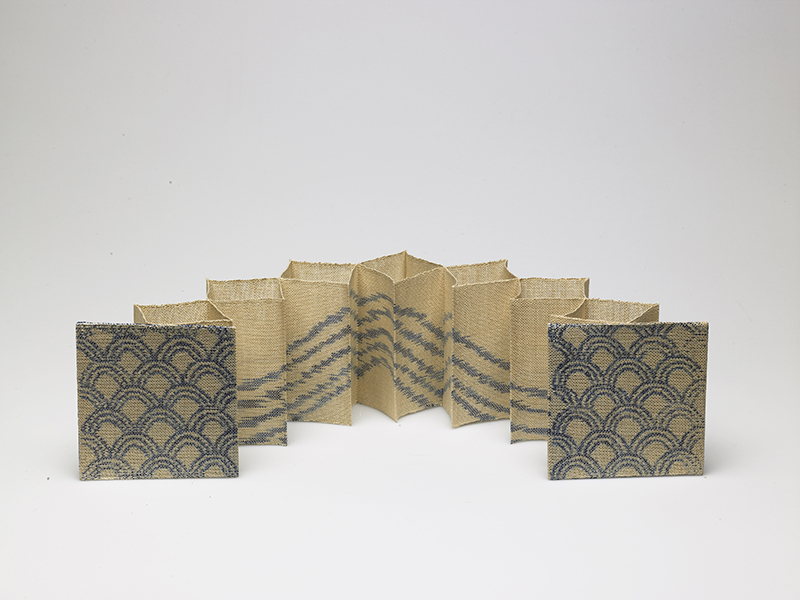

Wave by Sekimachi, 1980. Linen, transfer dye, buckram lining; height 4 3/8, overall length 18 inches. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, gift of the artist.

Sekimachi was born in San Francisco in 1926, the daughter of Japanese immigrants. She and her family were among the thousands of Japanese transplants who endured internment during World War II. Yet creativity blossomed in the midst of privation. Teachers among the detainees organized themselves into a school and held art classes. (Funds for materials were provided by charitable groups and donors.) The experience supported Sekimachi’s nascent talent and introduced her to role models.

Within a few years after the war, Sekimachi discovered her métier, and dove into weaving, making placemats and other functional objects to earn a living. Her path was forever changed by her teacher, the German émigré and weaver Trude Guermonprez (1910–1976), whose rational, Bauhaus-influenced sensibility was balanced by an openness to experimentation. Guermonprez introduced Sekimachi to the artistic possibilities of textiles, and encouraged her to investigate new methods of expression on the loom.

Her early casement fabrics—sheer, usually openweave cloth often used for curtains—were featured in national exhibitions such as the seminal show Designer Craftsmen U.S.A. 1953, organized by the American Craftsmen’s Educational Council and mounted at the Brooklyn Museum. More ambitious forms followed. Her big breakthrough was a series of complex, intersecting weaves made with a modern industrial material: nylon monofilament. Working on a twelve-harness loom, Sekimachi wove multiple layers together simultaneously, allowing the springy and slippery material to give threedimensional, sculptural form to the flat weave.

In their introduction to the catalogue for the Wall Hangings exhibition of 1969 at the Museum of Modern Art, curators Jack Lenor Larsen and Mildred Constantine called her work “at once complex and mysterious. Sekimachi is allowing her material to participate in determining the form.” She used the monofilament in its translucent form and dyed other compositions black for different effects. Like a Rohrschach image, these enigmatic, floating forms are open to many interpretations, from jellyfish, to wisps of smoke, spirits, and ghostly apparitions. Their success demonstrated Sekimachi’s ability to conceive and meticulously design complex and innovative compositions, the like of which had not been seen before.

In the 1980s, Sekimachi utilized the warp—the vertical threads that form the foundation of a textile—as a canvas by treating it selectively with color, whether applying it to individual strands, with a brush, using transfer dyes, or other means. She created subtle landscapes in woven linen accordion-fold books, a format based on a book of prints she owned by ukiyo-e master Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858). Sekimachi titled her works in homage to him and to other celebrated Japanese artists, as in Wave (1980), which employs transfer dye to create her stylized and ikatinspired interpretation of Under the Wave off Kanagawa (c. 1829–1833), also known as The Great Wave, by Hokusai.

The same inking method informs her peaked Ikat Box (1989), part of her Takarabako, or treasure box, series. Its solid volumetric appearance is deceiving, as Sekimachi created the entire form from a single flat weaving, as if it were a piece of paper. Origami folds and an interior armature create the box-like shape; selected lines of stitching added a linear element.

A love of experimentation and novelty has prompted Sekimachi to incorporate non-fabric materials into her creations, such as antique Japanese washi paper and kiri wood paper, known in the West as paulownia—a finegrained wood typically used in chests and small boxes. Sekimachi discovered it in the form of a paper-backed wood veneer and began to exploit its gentle bowing effect in box and basket shapes. In the last decade, however, she has returned to painted warps and square, flat-weave compositions in muted hues. She gives the pieces titles that are an homage to modern artists Paul Klee and Agnes Martin, who practiced a reductive aesthetic that Sekimachi has employed in her own reserved, self-contained work. Their achievements represent the unceasing search for form using an economy of means. Klee’s words, written down by Sekimachi in a notebook when a young student, summarize this perspective: “the watchword is simplicity—the art of saying much, but sayint it as simply as possible.”

As a nisei, or second-generation Japanese-American, Sekimachi imbued her work with a reverence for natural materials and for traditional techniques, like origami. It is also part of her story as a comic book hero. Her life story, entitled Weaver’s Weaver, Kay Sekimachi, is part of the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s online series for children entitled Drawn to Art: Ten Tales of Inspiring Women Artists. (Among them are Edmonia Lewis, Carmen Herrera, Corita Kent, and Mickalene Thomas.) For young girls in need of role models, Sekimachi’s story offers one lesson on how an unlikely path led to a brilliant career.

Seventy years may seem like a long time, but it is the blink of an eye for an artist who wakes up each morning with new ideas. A few years ago, Sekimachi began creating delicately woven string necklaces using shells that she accumulated on trips to Hawai’i. Other ideas beckon for an artist whose ceaseless experimentation with form and technique is her trademark. Throughout her career, she has kept Paul Klee’s words close, letting her work say much, as simply as possible.