Born into an aristocratic family in Sancerre, France, Anne Marguérite Joséphine Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville (Fig. 1), received an education that likely included drawing lessons. At the fall of the Bastille in 1789, she and her father fled Paris for their country house, where she commenced her artistic self-education. She came to America in 1807 with her husband, Jean Guillaume, Baron Hyde de Neuville, and lived in New York City and New Jersey for seven years. Later, she resided in Washington, DC, where her husband served as minister plenipotentiary from 1816 to 1822, during which time she became a celebrated hostess and influential figure. In 1818 she presciently stated that she had but one wish “and that was to see an American lady elected president.”1 Neuville is among the first women artists working in America to leave a substantial body of work. This article sheds light on this fascinating figure, whose life reads like a compelling historical novel. It coincides with the first major exhibition of her work: Artist in Exile: The Visual Diary of Baroness Hyde de Neuville, at the New-York Historical Society.2

While the exhibition was in gestation, the New-York Historical Society purchased or was given forty-three newly discovered watercolors and drawings, joining 122 works by the artist in the museum’s collection for a total of 165, and swelling the number of Neuville’s known works to more than two hundred. Before this trove appeared, noted authority on American art Theodore Stebbins termed Neuville one of the most interesting of the traveler-artists,3 and a few scholars placed her in the folk art tradition because she was self-taught.4 The evidence provided by the new cache proves that Neuville and her oeuvre were richer and more complex than either assessment.

Although the evidence for her education is lost, like other women of her station, Neuville probably received lessons in draftsmanship. At the time, drawing was highly valued and was standard in the curricula of academies and female seminaries in Europe and America.5 Even though she possessed a visual talent, her aristocratic class and the events of the French Revolution would have discouraged her from pursuing a career in the arts. Nevertheless, her family would have known about the impetus for more gender equality in education during the 1760s and 1770s.6

Like other women artists of her time, among them Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, who was also an autodidact, Neuville had limited options open to her. Vigée Le Brun was born a generation earlier and to an artist father, who facilitated her career as a professional artist. By contrast, Neuville’s parents intended her to become the head of a household. Whereas Le Brun married an artist and dealer and became a celebrated portraitist, Neuville married a hotheaded royalist sought by revolutionary factions. While her husband lived on the run or was imprisoned, Neuville, with her father, fled the main theater of the revolution in Paris for the relative safety of Sancerre in 1789.

From the evidence provided by the new works, Neuville began drawing in earnest when she was around eighteen years old at L’Estang (also known as L’Etang), the château near Sancerre that was owned by her grandmother Anne Marguérite Perrinet de Longuefin Rouillé de L’Etang. At eighteen, her grandmother had married a wealthy Parisian dealer in luxury fabrics, Jean Rouillé de L’Etang; they had five children, among them Neuville’s father, Étienne Jacques Rouillé de Marigny. There are only two portraits of Madame Rouillé extant, one a beautiful pastel by Maurice Quentin de La Tour that resurfaced recently but appeared too late to be included in the Historical Society’s catalogue (Fig. 8).7 It is one of many portraits of Madame Rouillé’s family members by La Tour,8who showed it at the Salon of 1738, where it garnered praise. The sitter is seen as a bibliophile and femme savante lost in thought, holding an open book with three others nearby. Her liquid brown eyes hold those of the viewer, who has interrupted this intimate moment.9

Although her patronage has never been studied, family tradition holds that Madame Rouillé commissioned a series of paintings from the noted landscapist Hubert Robert for her Paris residence, among them the one in Figure 9.10 At the beginning of the Directory, Madame Rouillé’s salon was among the first to reopen, and artists flocked to it.

Madame Rouillé was not only a role model for her granddaughter’s interest in art, but her identity solves the mystery of why Neuville was known as Henriette: to avoid confusion with her grandmother, she used Henriette instead of Anne Marguérite as her given name. It was at L’Estang, perhaps stimulated by her grandmother’s involvement in art, where Neuville began her artistic self-education. The château was pivotal in her life: she inherited her father’s share of the property from Madame Rouillé in 1802, and within two years she purchased those portions bequeathed to other relatives in order to consolidate full ownership.11

By examining Neuville’s early drawings, we can chart her exploration of various mediums. Isolated in the country, she lacked sophisticated artists’ materials. Because of the conflicts between France and England and the eventual blockade, graphite was unavailable, inspiring Nicolas Jacques Conté in 1795 to patent the Conté crayon and the ancestor of the pencil. The artist therefore turned to black chalk as her primary medium, occasionally supplementing it with white and red chalk.

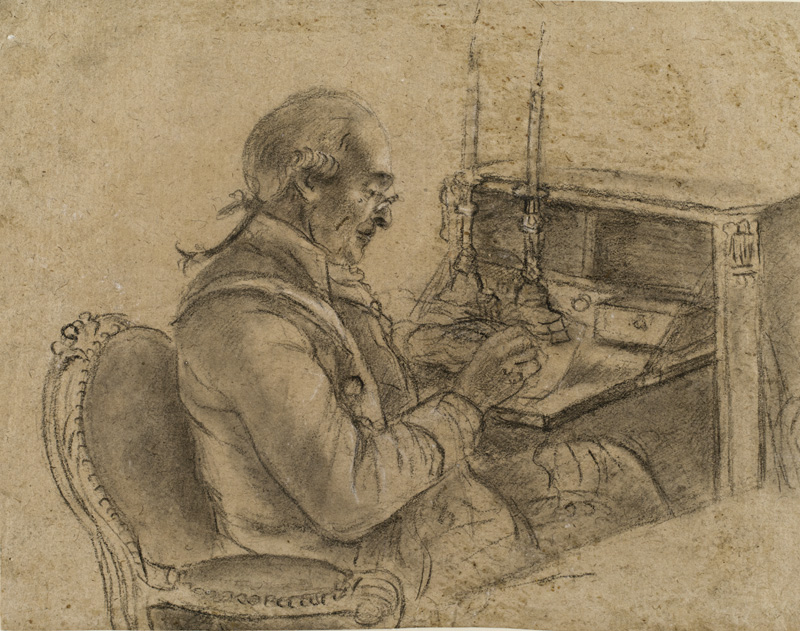

For her early subject matter, Neuville eschewed decorative work or fancy pieces, which were the customary provinces of women, opting to study the people around her, a sociological focus that she maintained throughout her life. She was attracted to people reading, writing, or drawing, some of whom were probably family members, such as the elderly couple depicted in a pair of drawings, each sitting in the same fauteuil near identical candlesticks. Some sitters were country folk, like a woman sewing (Fig. 4), boys wearing wooden shoes, and domestics. In these candid sketches, Neuville explored the potential of black chalk with stumping and gray watercolor to create volume, a style she developed from observation, not from technical instruction.

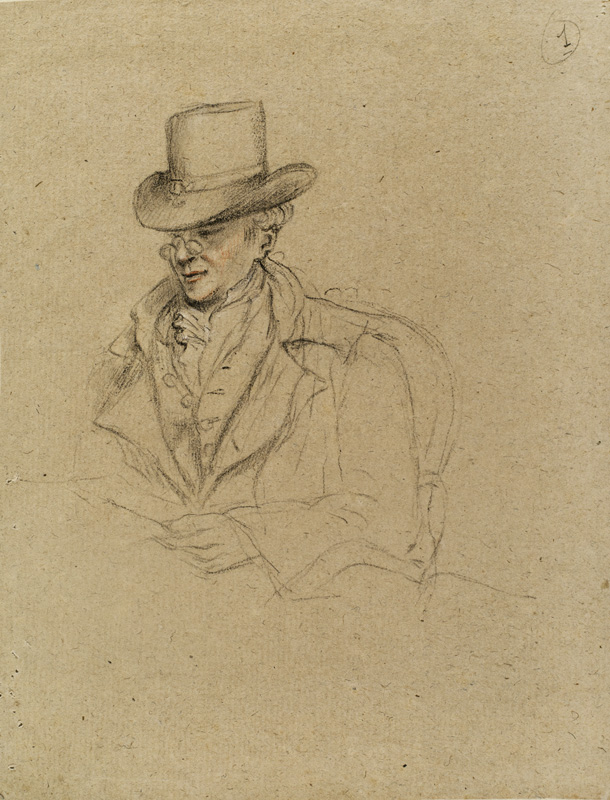

As she gained access to other mediums, the artist widened her horizons. Experiments with the eighteenth-century French trois crayons medium produced the portrait of her husband in Figure 2. Casting her artistic net wider, Neuville employed parchment in the refined likeness of Madame Heuters (Fig. 6), orchestrating a symphony of mediums to convey her sitter’s haunting psychological and physical state. She employed trois crayons over an under-drawing in her first use of graphite, suggesting that her husband had obtained it in England, which he began visiting in 1799 on royalist missions. She reinforced the snake-like curls on Heuters’s forehead—in the fashion David immortalized in his portrait of Madame Récamier (Fig. 7), an influential salonnière and friend of the Neuvilles’—with brown and black ink and Conté crayon. Finally, she added red accents to her sitter’s ears and rheumy eyes to suggest ill health, and gray watercolor to her proper right to put Heuters’s visage in relief and suggest the shadow that had fallen across her life.

Whereas the study of the live nude male model was taboo for women, the study of nude statues was not. Neuville’s drawings reveal that she turned to ancient sculpture to fill this gap. On one sheet she studied a reclining woman holding a fan or oil lamp from the lid of an Etruscan sarcophagus or funerary urn and a relief representing the semi-nude Roman god Vulcan. Among the other ancient sculptures she sketched was the head of a Venus that resembles the Venus de Milo.

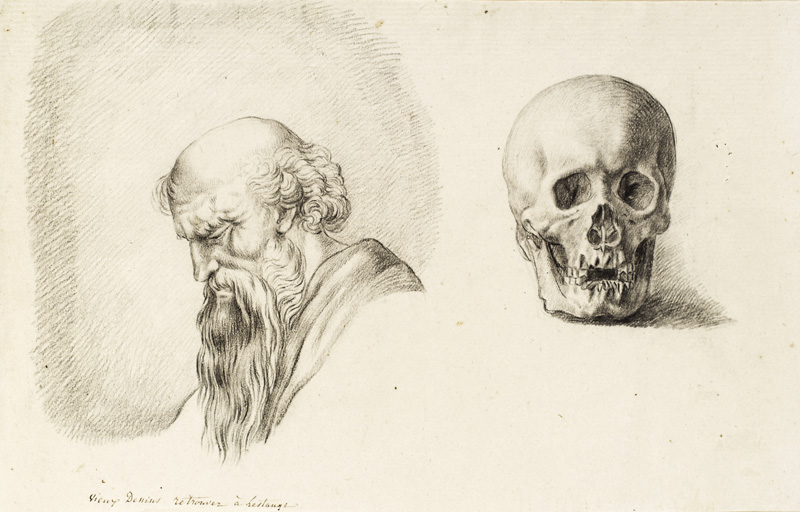

Neuville also studied two-dimensional works of art, following a time-honored method of artistic pedagogy. On one sheet she copied drawings in her grandmother’s collection: a seated ancient philosopher type in profile and a frontal skull modeled in chiaroscuro (Fig. 11). She no doubt also consulted a drawing manual: some of her portraits reveal that she frequently plotted the volumes of faces with centering and proportional lines.

Around 1805 Neuville acquired a more varied palette of watercolors. It is likely that her husband had purchased this important artistic medium during one of his trips to London. Her first full watercolor and, perhaps not coincidentally, her first landscape extant (Fig. 10), records the Neuvilles’ 1805 departure from La Charité-sur-Loire (near L’Estang) down the Loire River. After years of living under aliases and threat of arrest and execution, Jean Guillaume had irrevocably antagonized Napoleon Bonaparte, and they were fleeing for their lives, bound for Lyon, which for five months proved a safe haven. With this scene Henriette grasped her artistic goal: to capture and report vividly—in a different medium from her long-lost written journal—the people and places that piqued her interest.12 Since neither her gender nor the course of history allowed her to pursue her latent ambitions, she developed distinctive shorthand styles during her peregrinations for her visual diary—one employing watercolor for more finished works and another for sketching figures akin to eyewitness artists’ courtroom drawings.

The Neuvilles fled the environs of Lyon for Switzerland in 1805, after which Neuville embarked on a quest to seek a pardon for her husband from Napoleon. Without protection and accompanied only by her lady’s maid, she followed the emperor in the perilous wake of his battles until she reached Vienna. During her month-long wait for an audience, she was intrigued by a youth at an inn, painting him sitting on an Empire chaise near a Kachelofen, an Austrian rococo faience stove (Fig. 5). This watercolor, one of the forty-three newly discovered works by Neuville acquired by the New-York Historical Society, is the unique evidence of her stay in Vienna, where Napoleon finally granted a pardon in exchange for exile in America. Additional new sheets—among them a view of Constance, Germany, on the Swiss border; two watercolors of Swiss costumes; and studies of Spanish Roman monuments and costume—document this period before the Neuvilles embarked for America.

After arriving in their country of exile in 1807, the couple traveled up the Hudson River to Albany, and Neuville recorded priceless views that predate what are claimed as among the earliest scenes along the river (Fig. 12), The Hudson River Portfolio (1821–1825). Living in New York City for the next seven years, the couple associated with prominent individuals and in 1808 founded the progressive Economical School (École Économique), which was incorporated in 1810. Its mission was to educate émigrés and their offspring, many fugitives from uprisings in the French West Indies, and to offer affordable education to impoverished children. At the time, drawing was a prerequisite of a well-

educated person and a universal language. It was essential to the school’s curriculum, and Neuville made sketches of students at work—such as one of a young woman named Pélagie, one of more than twenty sheets in her “Economical School Series.” They are the only visual evidence of this New York institution, which remained open until 1822.

Neuville continued to copy works that impressed her. She consulted one of the most popular drawing manuals of the period: the Reverend William Gilpin’s Remarks on Forest Scenery, and Other Woodland Views (1791). She also drew after models by her artist friend Louis Simond, as well as after portraits of indigenous Americans by Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin and anonymous printmakers, while forging her own ethnographically significant portrayals.

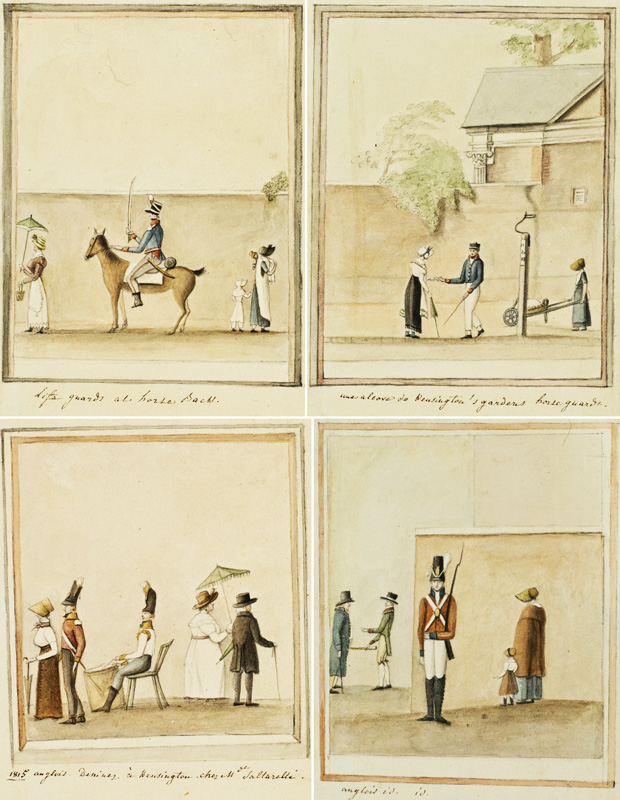

With the defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1814, the Neuvilles returned to France, only to be sent on a secret diplomatic mission to Italy to warn rulers about Napoleon’s plans for escaping from Elba. In 1815 Neuville spent several months in London, where she observed scenes near Kensington Gardens (Fig. 15) and traveled to Brighton, where she recorded the first dome of the Royal Pavilion (before John Nash modified it between 1815 and 1822). By 1816 the couple was back in America, Jean Guillaume serving as minister plenipotentiary in Washington, where Neuville continued her study of the ethnic diversity to be found in the new republic, including Chinese culture. In 1810 she had included an Asian visitor in a view of the intersection of Greenwich and Dey streets (Fig. 14), possibly Punqua Winchong, a merchant documented in New York and/or Washington in 1807, 1808, and 1818. In Washington she definitely painted Winchong, who attended one of the couple’s famous Saturday night parties there, and she also drew the chinoiserie pagoda in the park of the now- destroyed Château of Chanteloup.

Another Washington scene records the “Indian War Dance” performed before a crowd of six thousand during a visit of Plains Indian delegations to President James Monroe (Fig. 13). Neuville included at least two portraits: the woman sitting at the left, Hayne Hudjihini (Eagle of Delight), one of the wives of half-chief Shaumonekusse (Prairie Wolf), whom the artist portrayed wearing the horned headdress. Above the indigenous people she faintly sketched Monroe with four companions, including Baron Hyde de Neuville wearing a feathered bicorne hat. Afterwards, the Native Americans performed at the Neuvilles’ residence.

Neuville continued to draw and paint during her second residency until the couple’s return to France, when she executed what might be her final watercolor: a view of Versailles. As an aggregate, her newly discovered works—including another unpublished watercolor that popped up in mid-September and is in the exhibition—constitute an exciting missing link that allows a partial reconstruction of her artistic trajectory. They also enlarge the scope of this artist, whose works preserve her insatiable curiosity about people and places in unique vignettes of the early American republic during her two residencies. As her visual diary proves, Neuville was a singular artist and woman of substance who, in many ways, seems very modern.

Artist in Exile: The Visual Diary of Baroness Hyde de Neuville is on view at the New-York Historical Society to January 26, 2020.

1 Recorded on January 19, 1818, in the Louisa Catherine Johnson Adams Journal, Adams Family Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston. 2 The show is accompanied by a catalogue raisonné: Roberta J. M. Olson, Artist in Exile: The Visual Diary of Baroness Hyde de Neuville (New York: New-York Historical Society, in association with D Giles Ltd, 2019). See this volume for documents and specific information on the individual works discussed. 3 Theodore E. Stebbins Jr., American Master Drawings and Watercolors: A History of Works on Paper from Colonial Times to the Present (New York: Harper and Row, 1976), p. 57. 4 Outside of short articles and multiple reproductions of around two dozen of her works, there is only the thirty-seven-page exhibition catalogue by Jadviga da Costa Nunes and Ferris Olin, Baroness Hyde de Neuville: Sketches of America, 1807–1822 (New York and New Brunswick, NJ: New-York Historical Society and Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 1984). 5 Stebbins, American Master Drawings and Watercolors, pp. 93–94. See also Mary Kelley, Learning to Stand and Speak: Women, Education, and Public Life in America’s Republic (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006). 6 See the remarks of Louise Florence Pétronille Tardieu d’Éschavelles d’Épinay, as quoted in Mary D. Sheriff, “The Woman-Artist Question,” in Jordana Pomeroy et al., Royalists to Romantics: Women Artists from the Louvre, Versailles, and Other French National Collections (London and Washington, DC: Scala and the National Museum of Women in the Arts, 2012), p. 26. 7 Illustrated in its original frame in Catalogue des tableaux anciens et modernes: pastels, dessins et aquarelles des Écoles Italienne, Espagnole, Française, Flamande et Hollandaise . . ., Hôtel Drouot, Paris, May 10–11, 1897, p. 44, lot 162; also illustrated online in Neil Jeffares, Dictionary of Pastellists before 1800 at pastellists.com, no. J.46.274. 8 Catalogue des tableaux anciens et modernes, p. iii; Paul Albert Besnard, La Tour: La vie et l’oeuvre de l’artiste (Paris: Les Beaux-arts, édition d’études et de documents, 1928), p. 74. 9 Elise Goodman, The Portraits of Madame de Pompadour: Celebrating the Femme Savante (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), pp. 87–89, fig. 46. 10 See Catalogue des tableaux anciens et modernes, pp. iii–v, 22–25, lots 71–83. See also Pierre de Nolhac, Hubert Robert, 1733–1808 (Paris: Goupil & Cie, Manzi, Joyant & Cie, 1910), pp. 151–152; Exhibition of Paintings and Drawings by Hubert Robert (1733–1808) (New York: Wildenstein & Co., 1935), p. 5, nos. 1, 2; Katharine Baetjer, French Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art from the Early Eighteenth Century Through the Revolution (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2019), pp. 292–293. 11 Château de Lestang: Étude historique et architecturale, vol. 1 (Paris: Recherches et Études Appliquées, 2018), pp. 70–71. 12 Neuville’s journal is quoted by her husband in Jean Guillaume, Baron Hyde de Neuville, Mémoires et souvenirs du Baron Hyde de Neuville, ed. Viscountess Pauline Henriette Hyde de Neuville Bardonnet, 3 vols. (Paris: E. Plon, Nourrit, 1888–1892).

ROBERTA J. M. OLSON, curator of drawings at the New-York Historical Society, organized Artist in Exile and is the author of the accompanying catalogue.