Established in 1900 and in business until 1970, the Kalo Shop of Chicago was one of the most successful independent American silver makers of the twentieth century, creating finely designed, hand-wrought silver in a style that brought together the traditional and the modern. Notably, the Kalo Shop was founded and managed by women, at a time when women had scarcely even begun to approximate social, economic, and political parity with men. Chief among the founders was Clara Barck Welles, the firm’s guiding light for most of its existence. A woman both of her time and ahead of her time, Welles combined entrepreneurial drive with an artistic sensibility and a commitment to progressive principles. Amid the vigorous economic growth and dynamic social changes seen in the America of the early twentieth century, Welles and her colleagues forged a company that weathered the challenges of two world wars and the Great Depression, all the while making products that truly lived up to the firm’s motto: “Beautiful, Useful, and Enduring.”

Two distinct social, cultural, and political movements would inform the founders of the Kalo Shop, and in large measure made their enterprise possible. The first was the arts and crafts movement, which arose in the late Victorian era in Britain, the world’s most industrialized nation. The movement’s adherents argued forcefully that mechanization had debased the decorative arts and advocated a return to honest handcraftsmanship in the making of everything from textiles to metalwork. By the turn of the twentieth century, the movement had gained strong influence in the United States, leading to the formation of arts and crafts societies in large cities like Chicago and the organization of rural artist colonies around the country,1 all promoting the education and training of a new generation of artisans.

The second was the American women’s suffrage movement, with its concomitant demands for a wide range of social and economic reforms. By the late nineteenth century, even if a woman’s right to vote was decades from reality, a new spirit had emerged among American women, who were determined to achieve independence and self-sufficiency.

A self-made woman, deeply steeped in both the philosophy of the arts and crafts movement and the ideals of the suffrage campaign, Welles and her life story are emblematic, in many ways, of the story of the Kalo Shop. She came from humble beginnings. Clara Barck was born in 1868 to immigrant parents—her father had come to the United States from Finland; her mother was a Swiss native—in a village in upstate New York, the fourth of what would be six children, all daughters. The Barck family soon moved westward, first to Michigan in 1873, then on to Oregon in 1878. There, they settled and established a farm in the fertile Willamette River Valley. Just five years later Barck’s father died, leaving the women to run the farm. This they did until 1888, when they moved to Oregon City.

As a young woman, Barck worked in a succession of jobs and learned skills that, in retrospect, prepared her perfectly for her later career. She worked as a weaver in a large woolen mill; then, after completing a business course at a Portland college in 1890, she found employment as a bookkeeper and then as a clerk at a large Portland department store. Later, she supervised the upholstery department for Portland furniture maker Forbes and Breeden—work that honed both her aesthetic judgment and her skills at dealing with customers. By 1895 she was also, interestingly, active in a debating society.

In 1897, Barck’s mother sold the family farm and divided the proceeds among her daughters. The next year, Clara—who had been living in San Francisco and working at a department store—enrolled in a course in decorative design offered by the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. The new degree program, which proved especially popular with women, offered classroom studies in art and design as well as hands-on training in such crafts as ceramics and jewelry making.

Within a few weeks of receiving their degrees in 1900, Barck and five fellow women graduates of the Art Institute design program founded a shop, on September 1. They chose the name “Kalo”—a word from classical Greek that has the connotations “good,” “beautiful,” and “noble.” As the holder of a business degree, Barck was the natural choice for manager.

The Kalo Shop proved immediately popular. The workshop, in downtown Chicago, initially produced a wide range of goods, including wallpapers, leather accessories, lampshades, pottery, tiles, woven baskets, embroideries, handbags, copper items, and silver jewelry.

In the early days, the Kalo Shop employed women designers almost exclusively, offering them fair wages and a work environment that promoted creativity. Progressive entrepreneurial women like Barck and her colleagues had an almost missionary zeal, believing they could not only build a successful business and create jobs, but also promote equality for women and improve conditions for working people.

Education was a part of that mission. In 1905, at age thirty-six, Clara Barck married George Welles, a Chicago fuel dealer twenty-one years her senior. The two moved to a rambling farmhouse in the suburban town of Park Ridge, and the next year Clara Welles (as she will be referred to henceforth) realized her ambition to establish an arts and crafts school and workshop. The Kalo Arts Crafts Community produced a variety of items for sale at the Chicago retail store while offering classes to young apprentices, mostly women, in metalwork and jewelry making. To promote the new enterprise while employing her public speaking skills, Clara Welles delivered lectures to women’s clubs and civic groups on the topic of women and the arts and crafts.

By this time silver had emerged as the most popular category produced by the Kalo Shop. To increase production and move on to larger, more ambitious silver works, in 1907 Clara Welles hired the shop’s first professionally trained silversmith: Julius Olaf Randahl, who came from the workshops at Marshall Field and Company. Other master silver- and metalworkers followed. Over the next several years, as production increased and the Kalo Shop reputation spread, the Park Ridge workshops became a mecca for silversmiths—some of whom had trained in Scandinavia, others at East Coast firms like Tiffany and Gorham—as well as aspiring metalsmiths, designers, and jewelers. By 1914 more than fifty people were associated with the workshops.

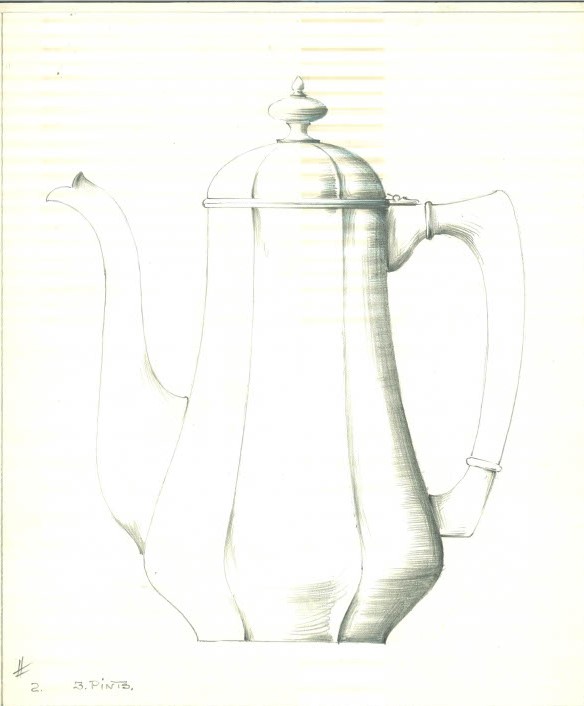

The faces would change over the years,2 but the same high and exacting standards had to be met by all Kalo Shop craftspeople. Clara Welles believed in excellence and continuity across the product lines. Before a piece was created, a formal design drawing, like the one in Figure 3, was submitted, to be kept on file and referenced for future works. While she welcomed innovation from the silversmiths and designers, she was protective of the primacy of the Kalo Shop brand. New designs, or older designs enhanced with new elements, might enter the product lines, but each had the Kalo Shop hallmark stamp on the bottom. Individual silversmiths were not supposed to sign pieces, though in some rare instances pieces have surfaced with artists’ initials as well as the Kalo stamp.

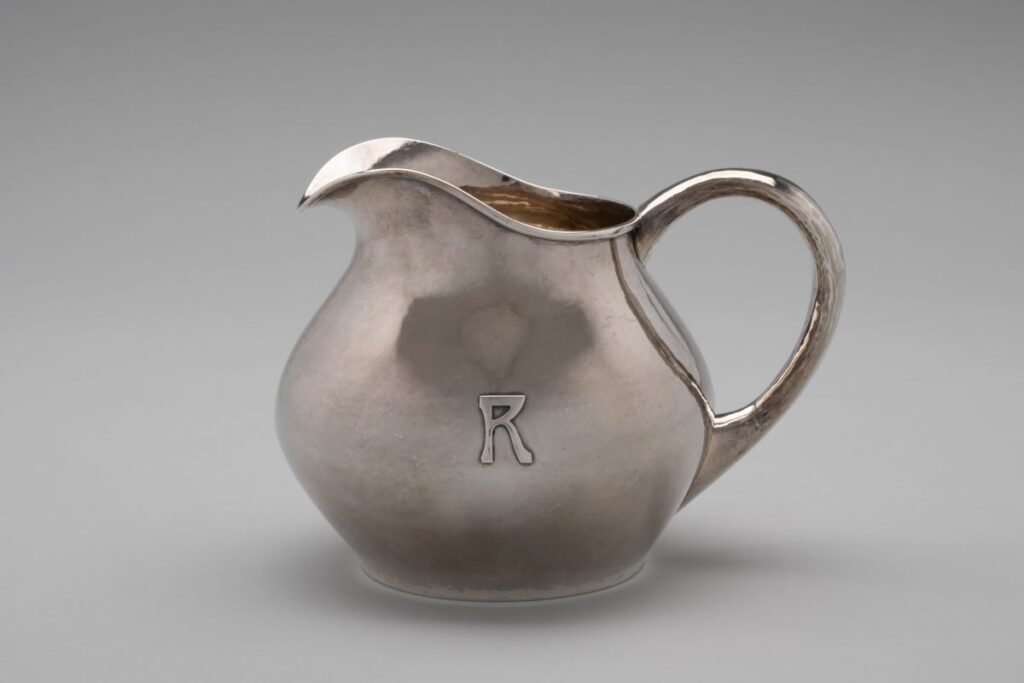

The output of hand-wrought silver from the Kalo Shop was remarkable and varied, ranging from tea sets, flatware, trays, covered dishes, and candlesticks to bowls, pitchers, boxes, jewelry, and many more forms. Virtually anything a client could need for the table or desktop was made by the shop. Most early Kalo Shop pieces display the solid, almost brawny arts and crafts style. The paneled pitcher in Figure 5 is a classic early Kalo design with eight vertical panels, offset spout, squared handle, and a hand-hammered surface that softens its overall look. In the chambered surface of the Kalo salad bowl in Figure 6 there is a play of light and shadow over the surface that reinforces its sculptural appearance. Its strong rectilinear design is often found in early Kalo Shop production. Even the QED monogram is a classic arts and crafts design.

Kalo pieces would become much more varied stylistically. Many took inspiration from nature, but with a sense of restraint rather than the flamboyance of art nouveau design. The candlesticks in Figure 9 take the form of soberly stylized tulips. Nature is evident again in both the vase in Figure 7, which resembles a morning glory flower in bloom, and in the small bud vase in Figure 8, with its subtle plant-like profile.

Silversmiths and designers at the Kalo Shop were aware of stylistic trends abroad, and adapted some for the American market. In Britain, architect-designer Charles Robert Ashbee popularized the incorporation of precious and semiprecious stones into silver designs. Malachite, lapis, pearl, and other stones appear in early Kalo pieces, often applied to objects such as serving pieces, small trays, and letter openers. The sugar tongs with inset coral cabochons in Figure 11 is an example.

Customers would come to the Kalo Shop for silver articles to mark special occasions, achievements, and milestones. Children’s silver was popular. Families would purchase a cup, plate, porringer, or children’s flatware to celebrate a birth or a first Christmas. These were often adorned with delightful woodland or barnyard animals, such as the lamb on the child’s cup in Figure 10—a rare instance where repoussé decoration appears in Kalo silver.

Many a bride and groom set up house with wedding gifts from the Kalo Shop bought by generous friends. These were often utilitarian items such as a set of salt shakers (Fig. 1) or a pepper grinder (Fig. 2). Specialized pieces like monogrammed strawberry forks (Fig. 12) would also have been a wonderful choice. The pie server shown in Figure 13—with a repoussé flower and applied initial “K”—is unusual and was likely the result of a collaboration between the buyer and Kalo designers.

Customization became a keynote of the Kalo Shop. Applied monograms appear quite frequently on Kalo pieces. The shop was also known for making inscribed commemorative pieces, such as the large double handled vase or loving cup dedicated to Morris L. Mossler on the occasion of his bachelor party dinner in 1911 (Fig. 14). Another example is a retirement bowl shown in Figure 15, dedicated to Richard Sheridan upon his retirement from the Webb C. Ball Company in 1916, and inscribed with the motto “IT’S A GOOD THING TO BE RICH✝IT’S A GOOD THING TO BE STRONG✝BUT IT’S A BETTER THING TO BE BELOVED BY MANY FRIENDS,” as well as with the names of those presenting the bowl. Items like these were made mainly between 1909 and 1920.

Clara Welles knew that not every customer could afford specialized work, and that very few were able to buy an entire silver service all at once. Kalo made several elegant, now-classic design lines, and kept them in production, allowing families to build and add to their collections over time. The number 18 bowl, with five upswept lobes, is a classic Kalo floriform shape (Fig. 18). The bowl was produced in small, medium, and large sizes and is easily found today. Another classic design is the pitcher in Figure 17, which was produced with a hollow-handled version (shown here) as well as a version with a strap handle.

By 1912 the Kalo Shop had become so successful and the brand so well known that the firm opened a branch on Fifth Avenue in New York, competing directly with Tiffany and Gorham. (That location would close in 1916 when Kalo cut back production in response to material and manpower shortages caused by the build-up to US entry into World War I.) Prosperity also allowed Clara Welles to devote more time to the women’s suffrage movement and other causes. She served on the executive board of the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association, and as one of her duties organized the participation of a large Illinois delegation in a massive suffrage parade in Washington, DC, on the eve of Woodrow Wilson’s presidential inauguration in 1913. (Such activism deepened the cracks that had appeared in her marriage. George asked Clara to file for divorce, and when the petition was finally granted she shocked the court by insisting that she wanted no alimony—she had a thriving business and did not need it.) Another piece of Clara Welles’s progressive social activism bears mention here: as World War I ended, she organized a then-novel program to train teachers in the decorative arts so that they, in turn, could help soldiers make handcrafted objects as rehabilitative therapy.

Purchases by an established, loyal clientele kept the Kalo Shop afloat during the war years. Afterwards, business picked back up, and Welles was able to rehire staff and hire new silversmiths. Many of the latter came from Scandinavia, and under their influence the Kalo Shop began to produce designs with a more rounded form, as often seen in the early work of the Danish silversmith Georg Jensen. An example of this transition is seen in a double melon-form tea and coffee set (Fig. 16).

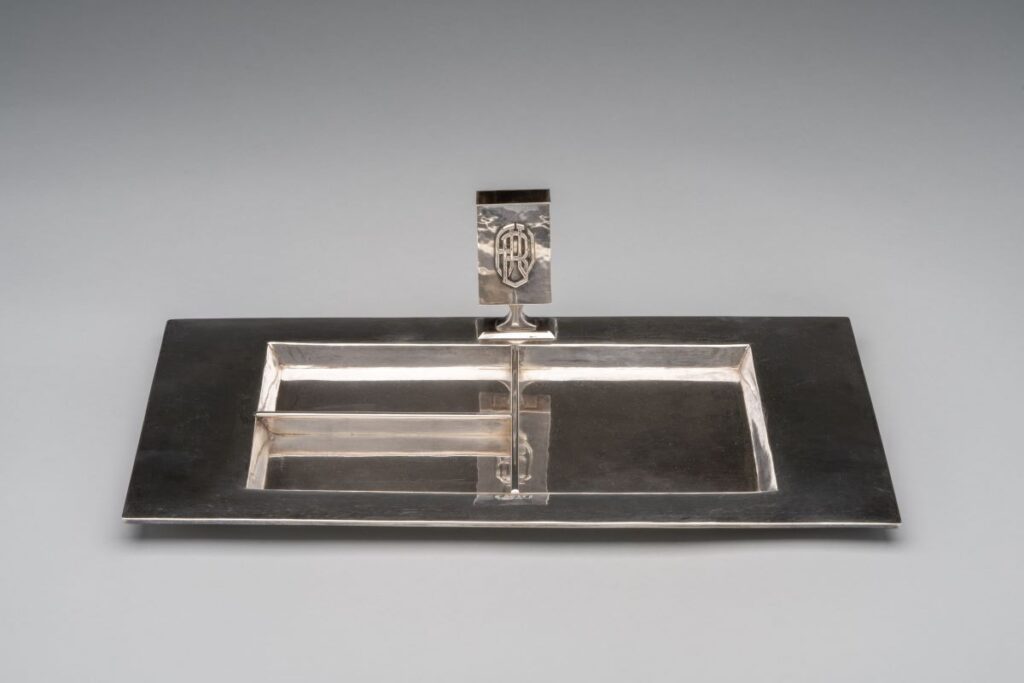

As an astute businessperson, Welles was quick to note social trends. Cocktail culture was thriving in the 1920s despite Prohibition, and smoking had become an accepted practice in society, even among women. Responding to the market, the Kalo Shop produced an array of elegant pieces for drinking such as a cocktail shaker with a whimsical repoussé scene of camels and pyramids, and cups customized with enameled yachting flags and inscriptions (Fig. 19). The Kalo ice bowl in Figure 20 contains a strainer, which allowed melted water to collect at the bottom of the bowl. (This particular piece was made for William M. Wright Sr., head of the Calumet Baking Powder Company and owner of Calumet Farms, a horseracing powerhouse in Kentucky.) Smoking appurtenances included a smoker’s tray (Fig. 21) with an attached match holder and compartments for cigarettes, lighters, cigar cutters, and such. The unusual cigarette dispenser in Figure 22 has a gilded interior to protect the silver from the chemicals in tobacco.

Perhaps because customization was a signature aspect of Kalo Shop and because Clara Welles carefully guarded the marketing of the brand, the firm sold its products only through its own shops. In the late 1920s, Kalo developed a limited “Norse line” of more modern, if heavy, pieces that were to be sold through department stores. But just as this line was set to launch, the stock market crashed, ending Kalo’s only foray into the wholesale business before it started. Today, Norse pieces are rare. The pitcher in Figure 24 is part of Kalo’s Norse line, as is the sauceboat in Figure 23. Each has an elegant, forthright design that includes applied three-bar embellishments and carved ebony handles, a mark of Danish influence. More Norse line pieces are shown in an image from the Kalo photographic archive (Fig. 25).

By making staff reductions and with the continued support of devoted patrons, the Kalo Shop muddled through the Depression. In 1939 Clara Welles declared herself tired of the midwestern winters and retired to San Diego, though she kept an occasional hand in the business and remained active in social and political causes. In 1959 she gave the Kalo Shop to the last four silversmiths working for the firm. These artists continued to run the shop until 1970. That year two of them died, and when replacements with sufficient skills to maintain quality standards could not be found, the Kalo Shop was closed down.

Clara Welles herself had passed away on March 14, 1965, a remarkable woman who possessed a powerful and too-rare combination of a visionary business acumen and a deep social conscience. She and the talented Kalo Shop men and women have left a legacy of timeless works of design, handmade in the belief that homes should be filled with objects that are as beautiful as they are useful. These pieces, many now more than one hundred years old, today look as fresh and as bold as they did on the day they were made.

I would like to acknowledge the pioneering research done by both Sharon S. Darling and Darcy L. Evon for their respective landmark publications Chicago Metal-Smiths: An illustrated History (Chicago Historical Society, 1977), and Hand-Wrought Arts and Crafts Metalwork and Jewelry 1890–1940 (Schiffer Publishing, 2013). I would also like to acknowledge Rosalie Berberian and her book Creating Beauty: Jewelry and Enamels of the American Arts and Crafts Movement (Schiffer Publishing, 2019). I encourage anyone who wants to learn more about Clara Welles and the Kalo Shop to seek out those publications. I wish to thank the late Paul Somerson, creator of the website Chicagosilver.com, and John P. Walcher, senior specialist in the decorative arts for Toomey and Company, for their guidance. Many thanks to Margo Grant Walsh, whose book Collecting by Design: Silver and Metalwork of the Twentieth Century inspired my interest in the Kalo Shop and refined my collecting.

1 The Society of Arts and Crafts was founded in Boston in 1897, and Chicago’s Arts and Crafts Society was founded the same year. American arts and crafts communities included Roycroft (founded 1895, East Aurora, New York), the Cornish (New Hampshire) Art Colony (1895), Rose Valley (1901, in Pennsylvania), and the Byrdcliffe Arts and Crafts Colony (1902, in Woodstock, New York ). 2 By one count, more than twenty independent businesses and studios were opened by artisans who had worked or trained at the Kalo Shop. Interestingly, one of them was the artist Grant Wood, who became a protégé of Clara Welles after exhibiting his metalwork at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1912 and made jewelry for the Kalo Shop. He opened the Volund Craft Shop with a fellow Kalo artisan in 1914, but it went out of business in 1916 and Grant went home miserably to Iowa. He returned to Chicago in 1930 when he won a $50 purchase prize from the Art Institute for American Gothic. See Darcy L. Evon “The Kalo Shop: Hand Wrought Metalwork and Jewelry” in A New Woman: Clara Barck Welles, Inspiration and Influence in Arts and Crafts Silver (Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, 2022), pp. 25–26.

STEVEN PAKIZ is a collector of arts and crafts silver and metalwork and an art appraiser living in Southern California.