Arriving this month at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, after a joint stop at Olana, the artist Frederic Edwin Church’s exquisite Moorish revival home in Hudson, New York, and, across the river, at the home of Church’s mentor, the Thomas Cole National Historic Site in the town of Catskill, Cross Pollination: Heade, Cole, Church, and Our Contemporary Moment is a new exhibition that does everything right. And in our unusually discordant contemporary moment, “doing everything right” is a salve. The show is calibrated to interest lovers of both traditional art and the cutting-edge art of today, and in doing so it gives the much-trodden Hudson River school a different, compelling look.

The exhibition is the work of curators from Crystal Bridges, Olana, and the Cole Historic Site, and it’s a smart collaboration, in large part funded by Art Bridges, Alice Walton’s new foundation that promotes hard-to-do collection sharing and partnerships. Anchoring the show are the sixteen canvases in Martin Johnson Heade’s Gems of Brazil, his ode to hummingbirds painted in 1863 and 1864. Both the paintings and their subjects are small, rarified, and riveting.

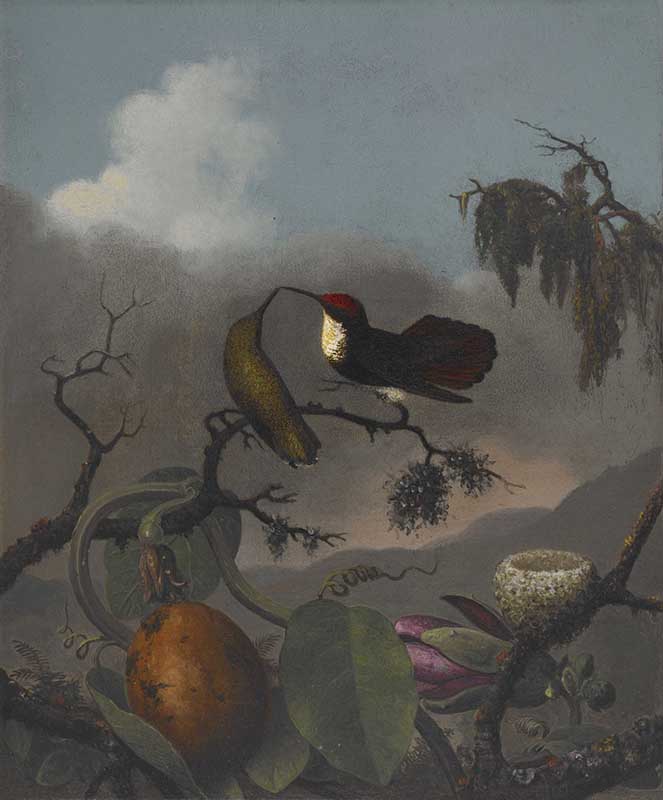

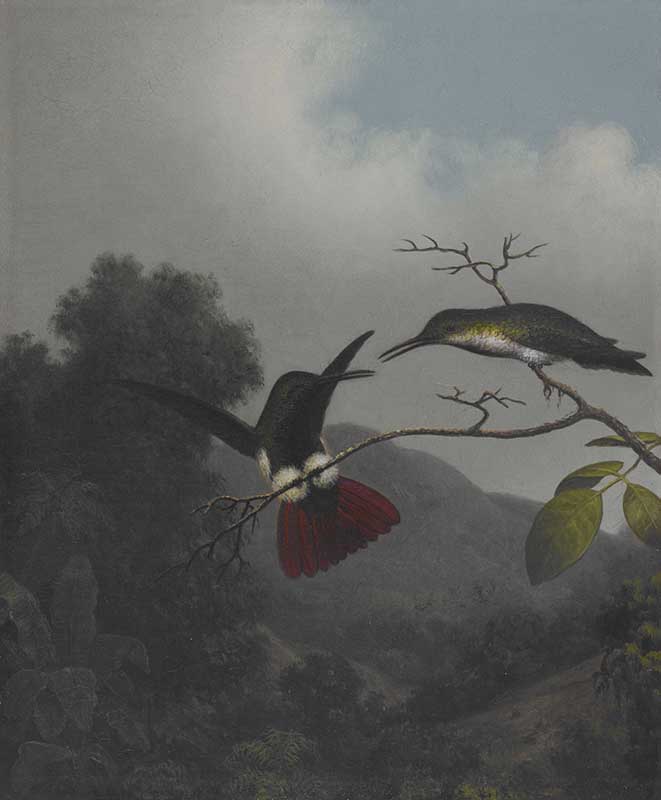

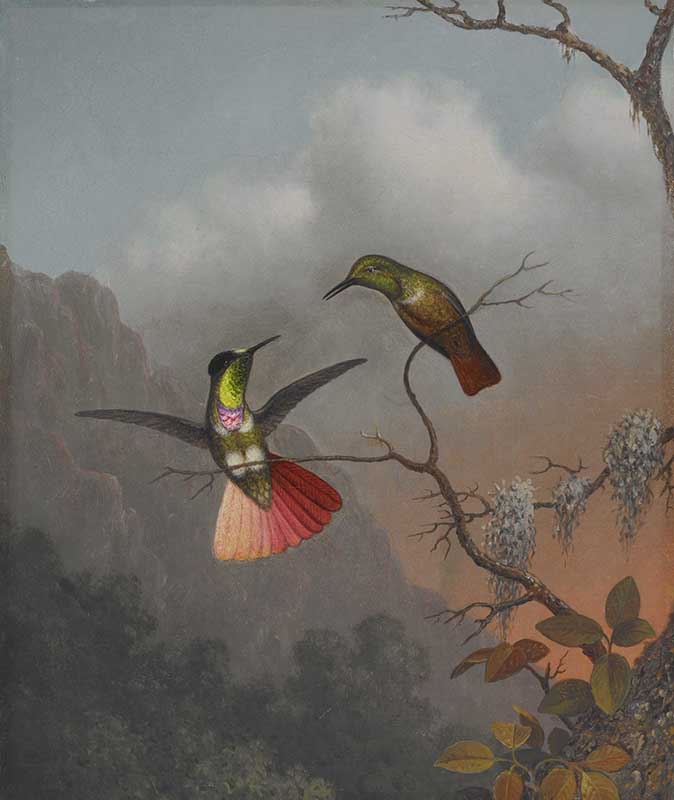

Heade was as much a naturalist as a painter. He traveled to Brazil to indulge his monomania for hummingbirds, their variety, setting, color, coupling, and parenting. The paintings are studies in iridescence, with sparkling moments of periwinkle, pineapple yellow, lime green, and ruby. Sinuous vines and wisps of moss enhance a sense of otherworldly, pre-Raphaelite composition.

Fig. 4. Ruby-Topaz from the Gems of Brazil series by Martin Johnson Heade (1819–1904), c. 1863–1864. Oil on canvas, 12 1/4 by 10 inches. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Fig. 5. Black-throated Mango from the Gems of Brazil series by Heade, c. 1863–1864. Oil on canvas, 12 1/4 by 10 inches. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Heade was inspired by John James Audubon’s mammoth Birds of America, published between 1827 and 1838, and hoped to produce his own sumptuously illustrated book on hummingbirds. Though the book never materialized, the paintings survived and became well known in Heade’s lifetime. Names like Frilled Coquette, Snowcap, and Black- throated Mango evoke an old-time fan dance. They’re the most fetching pageant around.

Fig. 6. Black-eared Fairy from the Gems of Brazil series by Heade, c. 1863–1864. Oil on canvas, 12 1/4 by 10 inches. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Fig. 7. Snowcap from the Gems of Brazil series by Heade, c. 1863–1864. Oil on canvas, 12 ¼ by 10 inches. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Hummingbirds are great pollinators, and this incisive, focused show looks at crosspollination of ideas as well as sex cells among plants. Ideas are, at their best, malleable creatures. Cross Pollination is an aesthetic delight, but it has a seriously academic side. That it has both is its real joy. Thomas Cole is represented by many good works in the show, among them View of Mount Etna from 1842 (Fig. 2). The painting is rooted in nature. Specificity is Cole’s guide. His ends, though, are a harmonious, even poetic, whole. Cole’s Italian subjects and his Hudson River scenes are moral allegories. These and his Voyage of Life and Course of Empire series aim for intellectual heights, as did the literary giants of Cole’s era.

Frederic Church was Cole’s brilliant student and his acolyte, but his work demonstrates that, while the ideas teachers convey can lead their students to emulation, they can also lead to dissent. His View on the Magdalena River from 1857 (Fig. 3) breaks with Cole. Church’s mature work is less poetic, uplifting, and moral. It’s frankly spectacular, even imperial. We’re carried to exotic places and become armchair explorers. Heade emulated both Church and Cole. Cole built the foundation of American landscape painting, presenting his paintings as the New World’s retort to Europe’s ruins, castles, and cathedrals. He extolled close looking at nature. Heade followed in these footsteps. Heade and Church were close friends, and in Gems of Brazil he gives us a microscopic view of the natural world that’s still every bit as majestic as Church’s. Heade’s Brazilian canvases combine landscape, still life, and even genre painting. Up close and personal, we’re treated to the private life of hummingbirds.

The elegiac mood of Cole’s late work signaled his concern that a swelling population and economic growth were destroying America’s forests and polluting its rivers. Heade, too, saw in the lives of hummingbirds nature’s exquisitely crafted interdependencies, and how easily they could be disrupted.

Fast forward to today. Cross Pollination deftly mixes old and new, from the expressions of Cole and Heade to those of artists such as Nick Cave and Vic Muniz. The conversation is never forced, in part because Cross Pollination’s curators selected on target art from today. Many of the artists had Gems of Brazil in mind as they worked. Some didn’t, but their art shows the Hudson River school still has the juice to influence artists of the twenty-first century. Aside from showing the debt living artists owe the American Old Masters, Cole, Church, and Heade seem refreshed by the young company.

Rachel Sussman’s series of photographs called The Oldest Loving Things in the World, like the work of Cole, Church, and Heade, are part art and part science. As intrepid as those artists, Sussman looked for resilience in nature and found it in a fifty-five-hundred-year-old moss in Antarctica and a spruce tree in Sweden nearly ten thousand years old. Their strange shapes and her deep-focus technique make for the look of science fiction.

Cave is a performance artist and textile designer. His work is a new take on immersion in nature. It’s bright, bold, and joyful but signals that nature’s more than a cause for celebration (Figs. 10, 14). It’s our job to steward it. Muniz is a Brazilian photographer, painter, and collagist. Living in São Paolo, he knew as much about flora and fauna in the jungle as New Yorkers know about butterflies in the bayou. His riffs on Heade are chromatically supercharged (Figs. 1, 11). Crystal Bridges has a fine collection of American landscapes (though few seascapes), and a visit to its permanent collection gives Cross Pollination even more depth and breadth.

The exhibition catalogue merits a mention. It is succinct, with three essays making key and refreshingly original points. Too many exhibition catalogues are packed with blather, and curators too often use them as ways to give their friends writing jobs, so tangents abound. The Cross Pollination book has too much front and back matter, but with so many institutions and founders involved, that’s hard to avoid. As at the Academy Awards, everyone gets to have a word. It’s fitting in a way, since this is a gem of a show. With so much good art and scholarship, bows are deserved all round.

Cross Pollination: Heade, Cole, Church, and Our Contemporary Moment is on view at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas, from November 20 to March 21, 2022.