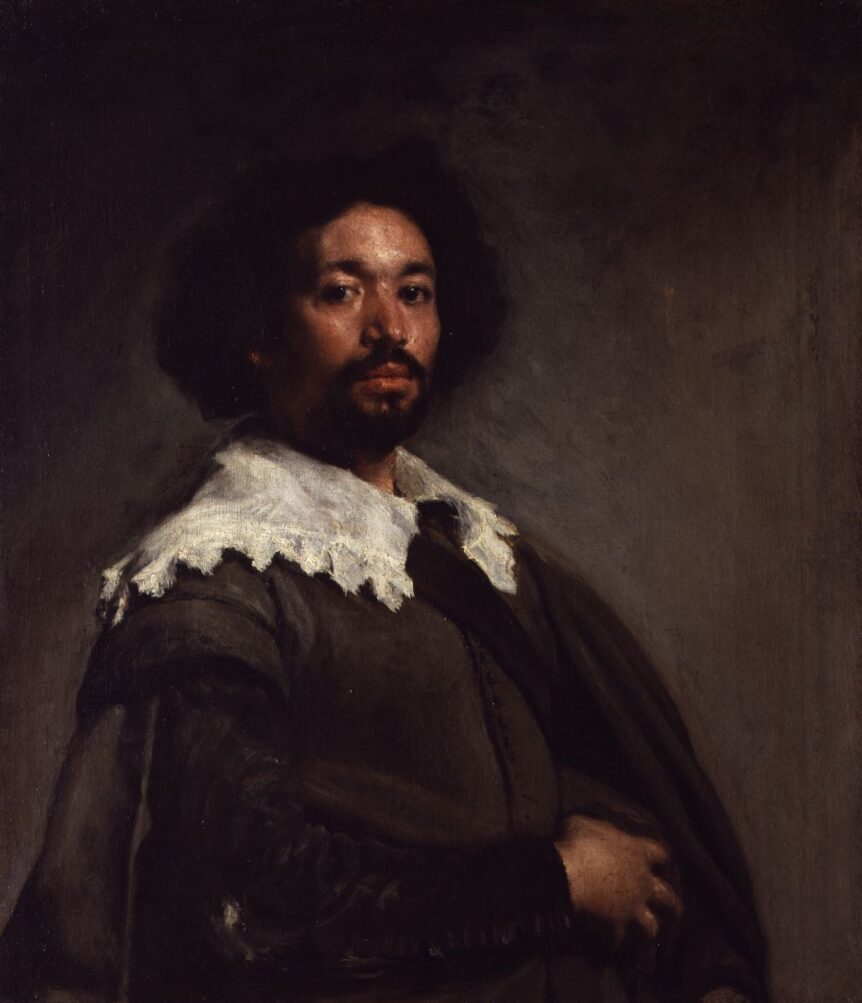

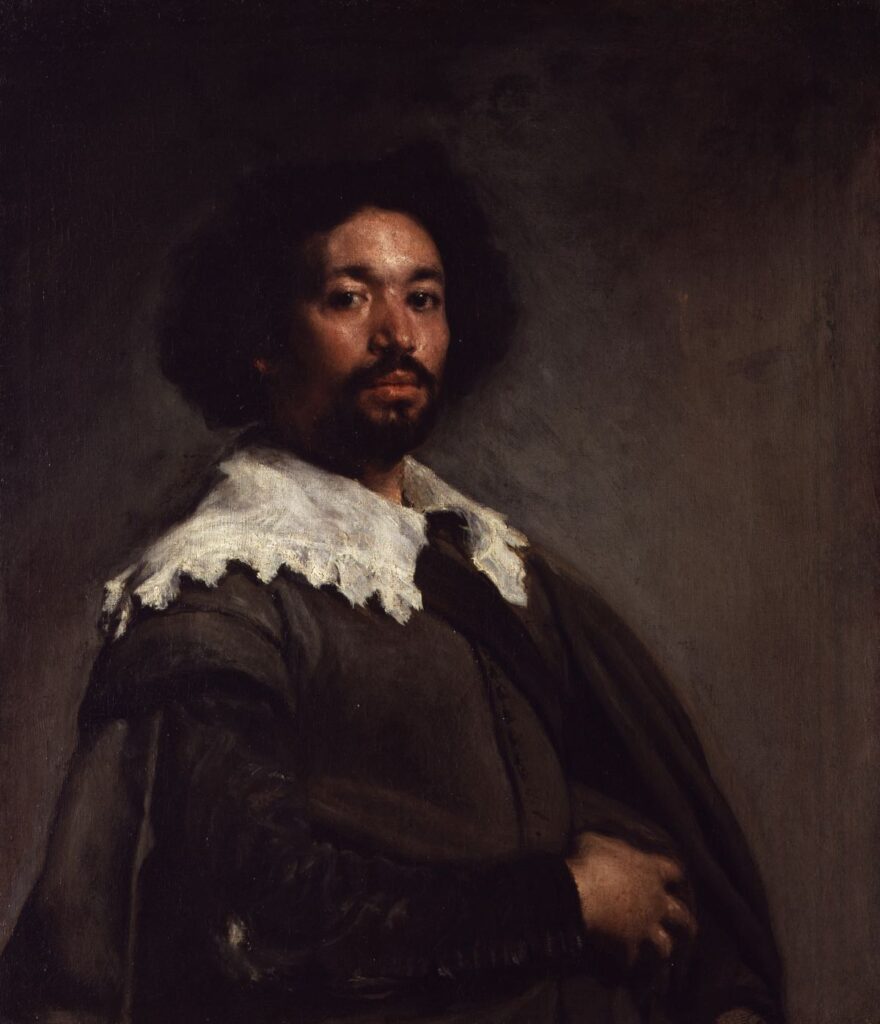

In its quiet and unobtrusive way, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Juan de Pareja, Afro-Hispanic Painter in the Age of Velasquez is one of the most necessary and unexpectedly interesting shows to be mounted anywhere in many years. First of all, it has excellent art, much of it by Velasquez himself. But it also introduces us to Juan de Pareja, Velasquez’s manumitted slave and a very able painter in his own right. Pareja is already famous as the subject of one of Velasquez’s finest portraits, which has been in the Metropolitan Museum since it was purchased in 1970 for the then-shocking price of $5,544,000.

The portrait of Pareja was painted in Rome in 1650, when he was forty-four years old. That same year, Velasquez signed the contract of manumission that would free Pareja four years later. Although Velasquez probably was not the only Old Master painter to have enslaved someone, I am unaware of any other painter who did, certainly none of his eminence. And I am equally unaware of any painter in the Old Master tradition, other than Pareja himself, who had been enslaved and perhaps remained so into the period when he was painting.

The exhibition does an excellent job situating Pareja in the context of Madrilenian art in the second half of the seventeenth century, when, together with a newer generation of artists—Claudio Coello and Antonio Palomino among them—he sought a chromatic drama very different from the somber monotones that predominated in Velasquez. His Calling of Saint Matthew (1661) and his Baptism of Christ (1667), both in the Prado, would stand as magnificent achievements even if we knew nothing of the astonishing details of the artist’s life.

The show also does full and worthy justice to Arturo Schomburg (1874–1938), a Puerto Rican-born Black intellectual who did so much to enhance our understanding of Black history and whose extensive research and collections of art and books formed the basis of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, part of the New York Public Library. Without his inspired examination of Pareja’s life and career, the present show could hardly have existed.

Juan de Pareja, Afro-Hispanic Painter in the Age of Velasquez • Metropolitan Museum of Art • to July 16 • metmuseum.org